Mobilizing for War

Mobilizing for War

World War II cost America 1 million casualties and over 300,000 deaths. In both domestic and foreign affairs, its consequences were far-reaching. It had an immediate impact on the economy by ending Depression-era unemployment. The war accelerated corporate mergers and the trend toward large-scale agriculture. Labor unions also grew during the war as the government adopted pro-union policies, continuing the New Deal’s sympathetic treatment of organized labor.

Presidential power expanded enormously during World War II, anticipating the rise of what postwar critics termed the “imperial presidency.” The Democrats reaped a political windfall from the war. Roosevelt rode the wartime emergency to unprecedented third and fourth terms.

For most Americans, the war had a disruptive influence—separating families, overcrowding housing, and creating a shortage of consumer goods. The war accelerated the movement from the countryside to the cities. It also challenged gender and racial roles, opening new opportunities for women and many minority groups.

The Allies prevailed in World War II because of the United States’ astounding productive capacity. During the Depression year of 1937, Americans produced 4.8 million cars, while the Germans produced 331,000 and the Japanese 26,000. By 1945, the United States was turning out 88,410 tanks to Germany’s 44,857. The U.S. manufactured 299,293 aircraft to Japan’s 69,910. The American ration of toilet paper was 22.5 sheets per man per day, compared with the British ration of three sheets. In Germany, civilian consumption fell by twenty percent, in Japan by 26 percent, in Britain by twelve percent. But in the United States, personal consumption rose by more than twelve percent.

During World War II, the federal government took an even larger economic role than it did during the World War I. To gain the support of business leaders, the federal government suspended competitive bidding, offered cost-plus contracts, guaranteed low-cost loans for retooling, and paid huge subsidies for plant construction and equipment. Lured by huge profits, the American auto industry made the switch to military production. In 1940, some 6,000 planes rolled off Detroit’s assembly lines; production of planes jumped to 47,000 in 1942; and by the end of the war, it exceeded 100,000.

To encourage agricultural production, the Roosevelt administration set crop prices at high levels. Cash income for farmers jumped from $2.3 billion in 1940 to $9.5 billion in 1945. Meanwhile, many small farmers, saddled with huge debts from the Depression, abandoned their farms for jobs in defense plants or the armed services. Over five million farm residents left rural areas during the war.

Overall, the war brought unprecedented prosperity to Americans. Per capita income rose from $373 in 1940 to $1,074 in 1945. Workers never had it so good. Rising incomes, however, created shortages of goods and high inflation. Prices soared eighteen percent between 1941 and the end of 1942. Apples sold for ten cents apiece; the price of a watermelon soared to $2.50; and oranges reached an astonishing $1.00 a dozen.

Many goods were unavailable regardless of price. To conserve steel, glass, and rubber for war industries, the government halted production of cars in December 1941. A month later, production of vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, radios, sewing machines, and phonographs ceased. Altogether, production of nearly 300 items deemed nonessential to the war effort was banned or curtailed, including coat hangers, beer cans, and toothpaste tubes.

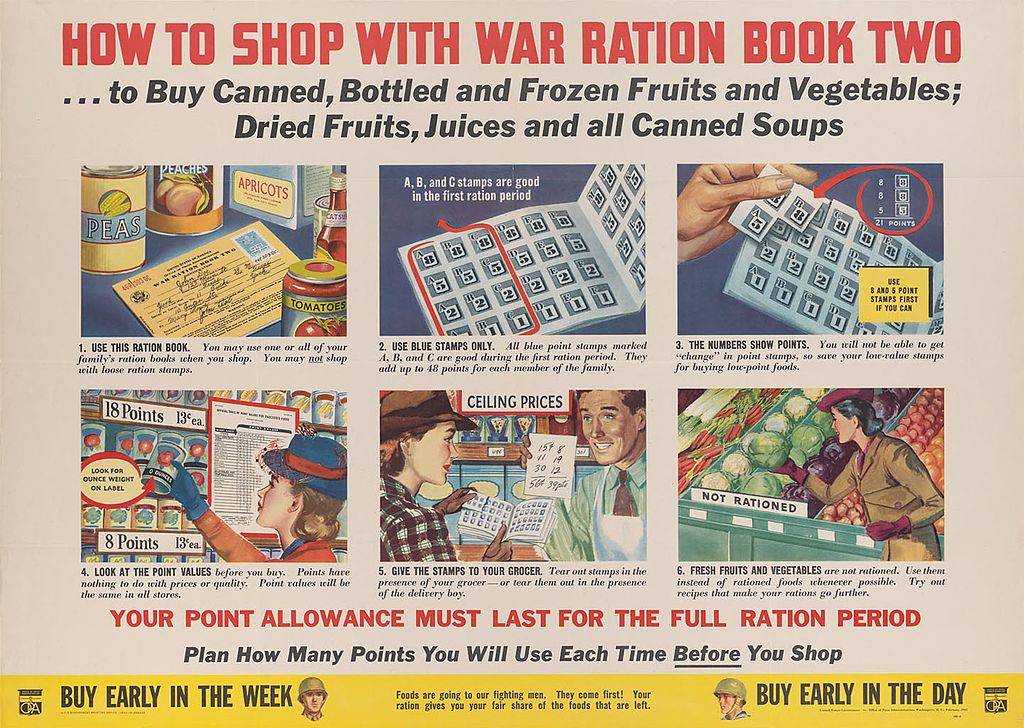

Congress responded to surging prices by establishing the Office of Price Administration (OPA) in January 1942, with the power to freeze prices and wages, control rents, and institute rationing of scarce items. The OPA quickly rationed food stuffs. Every month each man, woman, and child in the country received two ration books—one for canned goods and one for meat, fish and dairy products. Meat was limited to 28 ounces per person a week, sugar to eight to twelve ounces, and coffee, a pound every five weeks. Rationing was soon extended to tires, gasoline, and shoes. Drivers were allowed a mere three gallons a week. Pedestrians were limited to two pairs of shoes a year. The OPA extolled the virtues of self-sacrifice, telling people to “use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.”

In addition to rationing, Washington attacked inflation by reducing the public’s purchasing power. In 1942, the federal government levied a five percent withholding tax on anyone who earned more than $642 a year.

The war created 17 million new jobs at the exact moment when fifteen million men and women entered the armed services. As a result, unemployment virtually disappeared. Union membership jumped from 10.5 million to 14.75 million during the war.

Election of 1944

During the 1944 presidential campaign, President Roosevelt unveiled plans for a “GI Bill of Rights,” promising educational support, medical care, and housing loans for veterans, which Congress approved overwhelmingly in 1944. Unwilling to switch leaders while at war, the public stuck with Roosevelt to see the crisis through. The president easily defeated his Republican opponent, Governor Thomas Dewey of New York, receiving 432 electoral votes to Dewey’s 99 votes.

Hollywood Versus History

Molding Public Opinion

President Roosevelt hoped to avoid the crude propaganda campaigns that had stirred ethnic hatred during World War I. Nevertheless, anti-Japanese propaganda was intense. Movies, comic strips, newspapers, books, and advertisements caricatured Japanese by portraying them with thick glasses and huge buck teeth.

Motion pictures emerged as the most important instrument of propaganda during World War II. After Pearl Harbor, Hollywood quickly enlisted in the war cause. The studios quickly copyrighted movie titles like Yellow Peril and V for Victory. Off-screen, leading actors and actresses led recruitment and bond drives and entertained the troops. Leading directors like Frank Capra and John Huston made documentaries to explain “why we fight” and to show civilians what actual combat looked like.

History Through…

…Music

Music can serve essential purposes during wartime. It can boost morale, lift spirits, demonize the enemy, and help define the cause for which the nation is fighting. It can also give expression to some of the public’s deepest emotions.

As in World War I, there were many morale building songs like “We Did It Before and We’ll Do It Again” by George Tobias and Cliff Friend, and “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” by Frank Loesser. There were also jingoistic songs like “Der Fuehrer’s Face,” “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap”, and “Let’s Put the Axe to the Axis.” “God Bless America,” which Irving Berlin had written during World War I but which he had put away, became a new national anthem during the second world war.

But, in general, the most popular songs of the war years were deeply sentimental songs, like Berlin’s “White Christmas” or “Sentimental Journey” by Bud Green, Les Brown, and Ben Homer. Romantic ballads—such as “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You”—spoke to Americans’ pangs of separation and loss. The desire to remain upbeat in a time of global conflict was apparent in Harold Arlen’s “Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive.”

Hollywood Versus History

Film of World War II

Beginning in September 1941, a Senate subcommittee launched an investigation into whether Hollywood had campaigned to bring the United States into World War II by inserting pro-British and pro-interventionist messages in its films. Isolationist Senator Gerald Nye charged Hollywood with producing “at least twenty pictures in the last year designed to drug the reason of the American people, set aflame their emotions, turn their hatred into a blaze, fill them with fear that Hitler will come over here and capture them.” After reading a list of the names of studio executives—many of whom were Jewish—he condemned Hollywood as “a raging volcano of war fever.”

While Hollywood did in fact release a few anti-Nazi films, such as Confessions of a Nazi Spy, what is remarkable in retrospect is how slowly Hollywood awoke to the fascist threat. Heavily dependent on the European market for revenue, Hollywood feared offending foreign audiences. Indeed, at the Nazi’s request, Hollywood actually fired “non-Aryan” employees in its German business offices. Although the industry released a number of preparedness films (like Sergeant York), anti-fascist movies (such as The Great Dictator), and pro-British films (including A Yank in the R.A.F.) between 1939 and 1941, it did not release a single film advocating immediate American intervention in the war on the allies’ behalf before Pearl Harbor.

American entry into the war prompted many changes in Hollywood. Warner Brothers ordered a hasty rewrite of Across the Pacific which involved a Japanese plot to blow up Pearl Harbor, changing the setting to Panama Canal. The use of search lights at Hollywood premiers was prohibited. Jack Warner, well aware that the Lockheed aircraft plant in Burbank (a potential target for Japanese bombers) was located just blocks from his studio, ordered the painting of an enormous arrow pointing toward Burbank on the roof of one of the Warner sound stages with the words: LOCKHEED – THAT-A-WAY!

Hollywood’s greatest contribution to the war effort was morale. Many of the movies produced during the war were patriotic rallying cries that affirmed a sense of national purpose. Combat films of the war years emphasized patriotism, group effort, and the value of individual sacrifices for a larger cause. They portrayed World War II as a peoples’ war, typically featuring a group of men from diverse ethnic backgrounds who are thrown together, tested on the battlefield, and molded into a dedicated fighting unit.

Many wartime films featured women characters playing an active role in the war by serving as combat nurses, riveters, welders, and long-suffering mothers who kept the home fires burning. Even cartoons, like Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips, contributed to morale.

Off the screen, leading actors and actresses led recruitment and bond drives and entertained the troops. Leading directors like Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, made documentaries to explain “why we fight” and to offer civilians an idea of what actual combat looked like. In less than a year, twelve percent of all film industry employees entered the armed forces, including Clark Gable, Henry Fonda, and Jimmy Stewart. By the war’s end, one-quarter of Hollywood’s male employees were in uniform.

Hollywood, like other industries, encountered many wartime problems. The government cut the amount of available film stock by 25 percent and restricted the money that could be spent on sets to $5,000 for each movie. Nevertheless, the war years proved to be highly profitable for the movie industry. Spurred by shortages of gasoline and tires, as well as the appeal of newsreels, the war boosted movie attendance to near-record levels of 90 million a week.

From the moment America entered the war, Hollywood feared that the industry would be subject to heavy-handed government censorship. But the government itself wanted no repeat of World War I, when the Committee on Public Information had whipped up anti-German hysteria and oversold the war as “a Crusade not merely to re-win the tomb of Christ, but to bring back to earth the rule of right, the peace, goodwill to men and gentleness he taught.” Less than two weeks after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt declared that the movie industry could make “a very useful contribution” to the war effort. But, he went on, “The motion industry must remain free…I want no censorship.”

Convinced that movies could contribute to national morale, but fearing outright censorship, the federal government established two agencies within the Office of War Information (OWI) in 1942 to supervise the film industry: the Bureau of Motion Pictures, which produced educational films and reviewed scripts voluntarily submitted by the studios, and the Bureau of Censorship, which oversaw film exports.

At the time these agencies were founded, OWI officials were quite unhappy with Hollywood movies, which they considered “escapist and delusive.” The movies, these officials believed, failed to accurately convey what the allies were fighting for, grossly exaggerated the extent of Nazi and Japanese espionage and sabotage, portrayed our allies in an offensive manner, and presented a false picture of the United States as a land of gangsters, labor strife, and racial conflict. A study of films issued in 1942 seemed to confirm the OWI concerns. It found that of the films dealing with the war, roughly two-thirds were spy pictures or comedies or musicals about camp life—conveying a highly distorted picture of the war.

To encourage the industry to provide more acceptable films, the Bureau of Motion Pictures issued “The Government Information Manual for the Motion Picture.” This manual suggested that before producing a film, moviemakers consider the question: “Will this picture help to win the war-” It also asked the studios to inject images of “people making small sacrifices for victory—making them voluntarily cheerfully, band because of the people’s on sense of responsibility.” During its existence, the Bureau evaluated individual film scripts to assess how they depicted war aims, the American military, the enemy, the allies, and the home front.

After the Bureau of Motion Pictures was abolished in the Spring of 1943, government responsibility for monitoring the film industry shifted to the Office of Censorship. This agency prohibited the export of films that showed racial discrimination; depicted Americans as single-handedly winning the war; or which painted our allies as imperialists.