U.S. Responds to War in Europe

The United States Responds to War in Europe

As early as 1935, Roosevelt had come to realize that Hitler represented a threat to Western civilization. Yet the American public was strongly isolationist. Over the next six years, Roosevelt schemed to supply aid to the British and French. Many of his most influential advisers were against him. They argued that arms for the Europeans meant fewer arms for Americans.

Roosevelt responded to the European war by issuing a proclamation of neutrality. At the same time, he took a number of steps designed to help Britain. He pushed a fourth Neutrality Act through Congress, which permitted belligerents to purchase war materials, provided that they paid cash and carried the goods away in their own ships. This act aided the British because Britain controlled the Atlantic’s sea lanes. In September 1940, he persuaded Congress to pass the first peacetime draft in American history and signed an executive agreement with Great Britain, transferring fifty destroyers in exchange for 99-year leases on eight British bases in the Western Hemisphere.

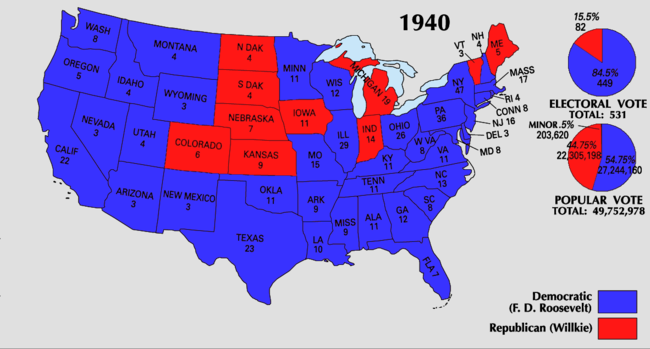

The European war dominated the election of 1940. During the campaign, Republican candidate Wendell Willkie charged Roosevelt with maneuvering the United States into the European war. Roosevelt was called a warmonger by Charles Lindbergh and the powerful labor leader John L. Lewis. On the eve of the election, Roosevelt responded, offering these reassuring words to American parents: “I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again: Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” Running for an unprecedented third term, Roosevelt easily defeated Willkie, receiving 449 electoral votes to the Republican candidate’s 82 votes.

After the election, Churchill informed Roosevelt that Britain could no longer afford to purchase war supplies. The president responded by persuading Congress to replace “cash-and-carry” with “Lend-Lease,” which gave the president authority to sell, exchange, lend, or lease war materiel to any country whose defense was vital to U.S. security. In November 1941, President Roosevelt offered lend-lease aid to the Soviet Union, which had been invaded by Germany in June 1941. Meanwhile, the American navy began to signal the location of German submarines to British destroyers.

A Collision Course in the Pacific

After Japan invaded China in 1937, relations between Washington and Tokyo deteriorated rapidly. In 1940, Japan occupied northern Indochina, a step toward its goal of capturing the oil supplies in the Dutch East Indies. To stop Japanese aggression, the United States placed an embargo on the export of scrap metal, oil, and aviation fuel to Japan. Also, President Roosevelt froze Japanese bank accounts in the United States. Harmed by these sanctions, Japan negotiated with the United States throughout 1941. The United States demanded that Japan withdraw immediately from Indochina and China—a concession that would have ended Japan’s dream of economic and military hegemony in Asia.

In a last ditch effort to avoid war, Japan promised not to march further south, not to attack the Soviet Union, and not to declare war against the United States if Germany and America went to war. In return, Japan asked the United States to abandon China. Roosevelt refused. In October 1941, the Japanese government fell, and General Hideki Tojo, the leader of the militants, seized power. War was imminent.

Most military experts expected Japan to attack the Dutch East Indies to secure oil and rubber. Before striking there, however, Japan moved to neutralize American power in the western Pacific.

Pearl Harbor

At 7:02 a.m., December 7, 1941, an army mobile radar unit set up on Oahu Island in Hawaii picked up the tell-tale blips of approaching aircraft. The two privates operating the radar contacted the Army’s General Information Center, but the duty officer there told them to remain calm. The planes were probably American B-17s flying in from California. In fact, they were Japanese aircraft that had been launched from six aircraft carriers 200 miles north of Hawaii.

At 7:55 a.m., the first Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbor, the main base of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Moored in the harbor were more than 70 warships, including eight of the fleet’s nine battleships. There were also 2 heavy cruisers, 29 destroyers, and 5 submarines. Four hundred airplanes were stationed nearby.

Japanese torpedo bombers, flying just 50 feet above the water, launched torpedoes at the docked American warships. Japanese dive bombers strafed the ships’ decks with machine gun fire, while Japanese fighters dropped high explosive bombs on the aircraft sitting on the ground. Within half an hour, the U.S. Pacific Fleet was virtually destroyed. The U.S. battleship Arizona was a burning hulk. Three other large ships—the Oklahoma, the West Virginia, and the California—were sinking.

A second attack took place at 9 a.m., but the damage had been done. Seven of the eight battleships were sunk or severely damaged. Out of the 400 aircraft, 188 had been destroyed and 159 were severely damaged. The worst damage occurred to the Arizona; a thousand of the ship’s sailors drowned or burned to death. Altogether, 2,403 Americans died during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor; another 1,178 were wounded. Japan lost just 55 men.

It was not a total disaster, however. Japan had failed to destroy Pearl Harbor’s ship repair facilities, the base’s power plant, or its fuel tanks. Even more important, three U.S. aircraft carriers, which had been on routine maneuvers, escaped destruction. But it had been a devastating blow nonetheless. Later in the day on December 7, Japanese forces launched attacks throughout the Pacific, striking Guam, Hong Kong, Malaya, Midway Island, the Philippine Islands, and Wake Island.

The next day, President Roosevelt appeared before a joint session of Congress to ask for a declaration of war. He began his address with these famous words: “Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date that will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.” Congress declared war on Japan with but one dissenting vote.