The Coming of World War II

The Coming of World War II

Adolf Hitler gained power in Germany by exploiting the psychological injuries inflicted on Germans by World War I. Tapping into an ugly strain of anti-Semitism in German culture, he blamed many of the nation’s economic woes on German Jews, who only constituted one percent of Germany’s population.

In addition, he attacked the Treaty of Versailles. Purged of so-called Jewish traitors, cleared of the blame for causing the war, freed from onerous reparation payments, and rescued from emasculating disarmament, Germany would rise anew and reclaim her position as a world leader.

The Treaty of Versailles had saddled Germany with a reparations bill of $33 billion. Unable to make the interest payments, Germany’s economy suffered a wave of inflation without precedent. Forty million marks were worth one cent. A newspaper cost 200 million marks. In 1924, Charles Dawes, a prominent American banker, worked out a proposal (the Dawes Plan) that reduced the reparations bill to $2 billion and provided Germany with an American loan. Nevertheless, even this burden was more than Germany could pay.

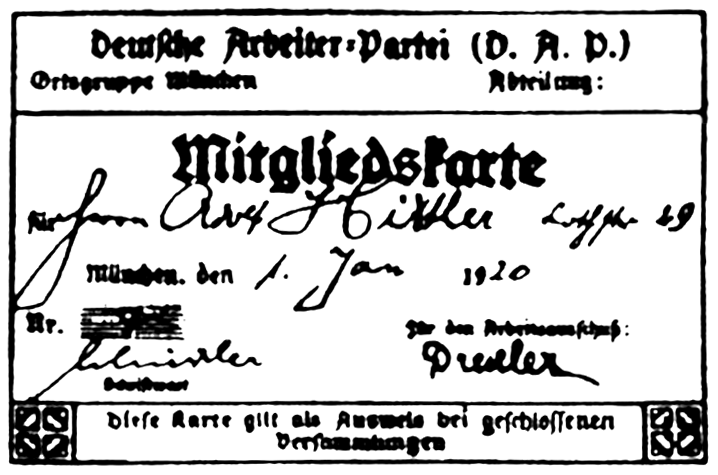

Hitler’s drive for political power began in 1919 when he joined a small party, later known as the Nazis. This party demanded that all Jews be deprived of German citizenship, and that all German-speakers be united into a single country. A brilliant propagandist, organizer, and orator, Hitler gave the Nazi movement a potent symbol: the swastika, raised party membership to 15,000 by 1923, and formed a private army, the storm troopers, to attack his political opponents. In the fall of 1923, Hitler engineered a revolt, the Beer Hall Putsch, to overthrow Germany’s five-year-old republic. The uprising was quickly suppressed, the Nazi party was ordered dissolved, and Hitler was imprisoned for nine months.

While in jail, Hitler wrote a book, Mein Kampf (My Struggle), which laid out his beliefs and vision for Germany. He called on Germans to repudiate the Versailles Treaty ending World War I, rearm, conquer countries with large German populations like Austria and Czechoslovakia, and seize lebensraum (living space) for Germans in Russia. Following his release from prison, Hitler persuaded the German government to lift its ban on the Nazi party. In 1928, the Nazis polled just 810,000 votes in German elections; however, in 1930 after the Depression began, they polled 6 ½ million votes. Two years later, Hitler ran for president. He lost, but received 13 ½ million votes—37 percent of all votes cast. The Nazis had suddenly become the single largest party in the German parliament. In January 1933, Germany’s president named Hitler chancellor. A year and a half later Hitler was Germany’s dictator.

Within months of becoming chancellor, Hitler’s government outlawed labor unions, imposed newspaper censorship, and decreed that the Nazis would constitute Germany’s only political party. The regime established a secret police force, the Gestapo, to suppress all opposition and required all children, ten years and older, to join youth organizations designed to inculcate Nazi beliefs. By 1935, Hitler had transformed Germany into a fascist state. The government exercised total control over all political, economic, and cultural activities.

Anti-Semitism was an integral part of Hitler’s political program. The 1935 Nuremberg Laws forbade intermarriages, restricted the property rights of Jews, and barred Jews from the civil service, the universities, and all professional and managerial occupations. On the night of November 9, 1939—a night now known as Kristallnacht (the night of the broken glass)—the Nazis imprisoned more than 20,000 Jews in concentration camps and destroyed more than 200 synagogues and 7,500 Jewish businesses.

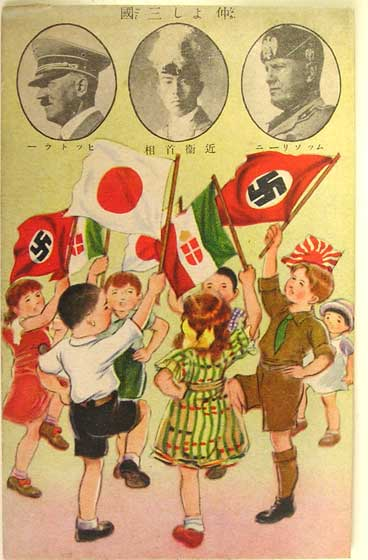

During the 1930s, a series of threats to world peace arose. Japan attacked China. Italy attacked Ethiopia. Nazi Germany rearmed, occupied the Rhineland, annexed Austria, and seized Czechoslovakia.

Conflict in the Pacific

The first major threat to international stability following World War I came in the Far East. Chronically short of raw materials, Japan was desperate to establish political and cultural hegemony in Asia. In September 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria, reducing the Chinese province to a puppet state. President Hoover rejected a military response and also refused to impose economic sanctions against Japan. He simply refused to recognize the new Manchurian government since it was based on force.

Expecting bolder measures, Japan ignored this slap on the wrist and concluded that the United States would not use military might to oppose its designs on the Far East. In 1934, Japan terminated the Five-Power Naval Treaty of 1922, which had limited its naval power in the Pacific. In 1937, Japan invaded China. In response, the League of Nations sponsored a conference at Brussels in November 1937. As the delegates debated whether or not to impose economic sanctions against Japan, the United States announced it would not support sanctions. The conference adjourned after passing a report that mildly criticized Japanese aggression.

Any doubts regarding the U.S. desire to avoid war vanished a few weeks later. In December 1937, Japanese aircraft bombed the Panay, a U.S. gunboat stationed on the Yangtze River near Nanking, killing three Americans. While the attack angered the public, few calls for war rang out. The response was wholly different from those following the sinking of the Maine or the Lusitania. The United States quickly accepted Japan’s apology, indemnities for the injured and relatives of the dead, promises against future attacks, and punishment of the pilots responsible for the bloodshed.

Italy

Benito Mussolini’s Italy posed another threat to world peace. Mussolini, Italy’s ruler from 1922 to 1943, promised to restore his country’s martial glory. Surrounded by storm troopers dressed in black shirts, Mussolini delivered impassioned speeches from balconies, while crowds chanted, “Duce! Duce!”

His opponents mocked him as the “Sawdust Caesar,” but for a time his admirers included Winston Churchill and Will Rogers, the humorist. Cole Porter, the popular songwriter, referred to the Italian leader in a line in one of his smash hits. “You’re the top,” he wrote, “you’re Mussolini.”

Mussolini invented a political philosophy known as fascism, extolling it as a “third way,” an alternative to socialist radicalism and parliamentary inaction. Fascism, he promised, would end political corruption and labor strife while maintaining capitalism and private property. It would make trains run on time. Like Hitler’s Germany, fascist Italy adopted anti-Semitic laws banning marriages between Christian and Jewish Italians, restricting Jews’ right to own property, and removing Jews from positions in government, education, and banking.

One of Mussolini’s goals was to create an Italian empire in North Africa. In 1912 and 1913, Italy had conquered Libya. In 1935, he provoked war with Ethiopia, conquering the country in eight months. Two years later, Mussolini sent 70,000 Italian troops to Spain to help Francisco Franco defeat the republican government in the Spanish Civil War. His slogan was “Believe! Obey! Fight!”

Germany

A third threat to world peace came from a revived Germany. Hitler had vowed to reclaim Germany’s position as a world leader. True to his word, he pulled Germany out of the League of Nations and secretly began to rearm. In 1935, he publicly announced that he was building an air force and a 550,000-man army. He also declared that Germany would have a peacetime draft, a clear violation of the Treaty of Versailles.

Next, Hitler concentrated on forging alliances with nations that shared Germany’s taste for expansion and aggression. Germany and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact (forerunner of a full-scale military alliance) in 1936. Shortly thereafter, Germany formed the Rome-Berlin Axis with Italy’s fascist dictator, Mussolini. Also in 1936, German troops re-occupied the Rhineland, the German-speaking region between the Rhine River and France. Once again, France and Great Britain did not oppose Hitler’s bold advance, for they believed (or wanted to believe) the Rhineland would satisfy his ambitions.

The Rhineland, however, only whetted Hitler’s appetite. Intent on reuniting all German-speaking peoples of Europe under the “Third Reich,” Hitler annexed Austria in 1938 and imprisoned the country’s chancellor. Once again, the British and the French acquiesced, hoping Austria would be Hitler’s last stop. Later that year, he demanded the Sudentenland, the German-speaking region of western Czechoslovakia.

This time France and Britain felt compelled to act. In September 1938, Edouard Daladier, the premier of France, and Neville Chamberlain, Britain’s prime minister, met with Hitler in Munich, Germany, to determine whether he had further designs on Europe. Fearing they could not count on each other to use force, British and French leaders eagerly accepted Hitler’s promises not to seek additional territory in Europe. Upon arriving in England, Chamberlain told his anxious countrymen that he had returned with an agreement that guaranteed “peace in our time.” In less than a year, Munich would become synonymous with shameful appeasement, and Chamberlain would be vilified for believing Hitler’s lies.

In August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression treaty. In exchange for the pact, Hitler agreed to grant the Soviet Union a sphere of influence over eastern Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Finland, and Bessarabia (northeastern Romania), while Stalin approved Germany’s designs on western Poland and Lithuania. With his eastern front protected from attack, Hitler was now prepared for war.

Hidden History

Fascism

Today, the word “fascist” is used exclusively in a negative way: As a label to belittle one’s political opponents. But beginning during World War I in Italy and extending through the World War II, advocates of fascism claimed that it represented a “third way”—an alternative to Communism and free market capitalism and to liberal democracy and Marxism.

Dictionaries and encyclopedias typically define fascism as a political system headed by a dictator in which the government controls business and labor and opposition is not permitted. But fascism is something more than an authoritarian system of government. Essential elements include:

- Extreme nationalism.

Fascists view the nation as an organic racial community, rooted in a common history, that must be purged of impurities and that must suppress all class conflicts. The Nazi’s hyper nationalism was evident in an emphasis on racial hierarchy, regarding Aryans as the master race, on anti-Semitism, intense hostility toward Jews, and on Social Darwinism, the view that there is a struggle for dominance among nations and racial groups rooted in the Darwinian notions of natural selection and “survival of the fittest.”

- A state-directed economy.

Rather than owning or operating the means of production, fascist regimes exerted control indirectly: by establishing cartels to control manufacturing, commerce, and finance, marketing boards to control agricultural production, licensing of most economic activities, and strict controls over imports.

The political ideology of the Nazi Party was called National Socialism. That is, the economy was to operate in the interest of the nation as a whole. Individual ownership of property remained, but was supplemented by public works projects (including rearmament), the elimination of independent labor unions, and social welfare policies that included state-provided health care and pensions.

- A glorification of militarism, youth, and masculinity.

Rather than viewing violence as intrinsically evil, fascists consider violence a necessity to defeat political opponents, suppress degenerate or biologically weaker peoples, and triumph in the Darwinian struggle of nations. Fascism tends to celebrate such supposedly “masculine” virtues as virility and vigor.

- The cult of the charismatic leader.

Fascism touts the need for a bold, decisive, manly, uncompromising leader who single-handedly embodies the will of the people. Theatricality is a key attribute of the fascist leader, evident in impassioned speeches and dramatic gestures.

- Mass mobilization.

Mass rallies sought to symbolize national unity and power. One 1934 Nazi Party Congress, which attracted 700,000 supporters, was documented and dramatized in one of the most influential films in history, Leni Reifenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. A masterpiece of propaganda, Triumph of the Will treats the rally as a symbol of Germany’s national regeneration in the wake of the military defeat, political upheaval, and economic deprivation. The film cloaks the rally in the pageantry and heroism of ancient Greece and Rome with elements of German mythology thrown in and shows how Hitler promised to restore a defeated, humiliated nation and make it a world power.

The Specter of Munich

No historical analogy has exerted more influence on America’s post–World War II use of military force than the decision of Britain and France to pursue a policy of appeasement toward Adolf Hitler in 1938.

Under an agreement reached in Munich agreement, Hitler was allowed to annex the German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia in return for a promise that this would be his last territorial demand. Neville Chamberlain, Britain’s prime minister announced that the agreement would ensure “peace in our time.”

On October 10, 1938, Nazi Germany formally took control of the Sudetenland, the iron-rich portion of Czechoslovakia containing most of that country’s ethnic German population. But less than a year later, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, and World War II began. A united Czechoslovakia might have blocked Germany’s invasion of Poland, halting Hitler’s war plan in its tracks.

The take-away: Weakness invites aggression that can lead to war.

Ever since, Presidents have invoked the lessons of Munich to argue that that capitulating to the demands of an aggressive dictatorship only invites further aggression and makes inevitable a larger war

Harry Truman invoked the lesson of Munich in 1950 when he defended American intervention in the Korean war by drawing parallels between the way “Communism was acting in Korea” and the way “Hitler had acted ten, fifteen, twenty years earlier.’’

When Lyndon Johnson was asked why we were in Vietnam, he supposedly said he did not want to be a “Chamberlain umbrella man.”

George H. W. Bush said, during Operation Desert Storm, “If history teaches us anything, “it is that appeasement doesn’t work.” Twelve years later, his son, George W. Bush echoed his father’s warning in calling for a U.S. invasion of Iraq.

Arguing for airstrikes against Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad, Secretary of State John Kerry warned that the nation faced a “Munich moment.”

The Munich analogy is used by leaders to justify military action and to discredit those who oppose the use of military force.