The United Nations

The United Nations

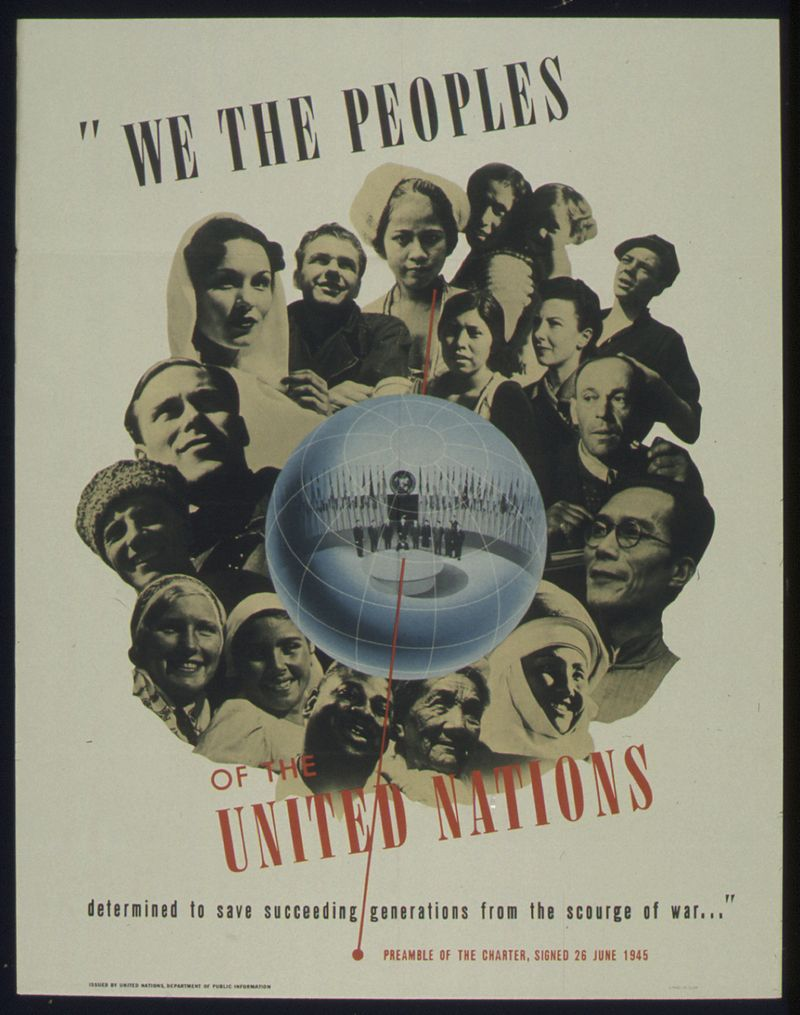

World War I held many lessons for leaders during and after World War II. Among those lessons was the need for an international organization to preserve peace, while avoiding the mistakes made by President Woodrow Wilson which led the United States to avoid joining the League of Nations.

Creating the United Nations was not easy. In January 1942, 26 Allied nations made a commitment to forming a United Nations. But President Franklin D. Roosevelt death in April 1945 placed any plans for a United Nations at risk. However, the new president, Harry S. Truman, was deeply committed to an international peacekeeping organization. For fifty years, he had carried in his pocket a folded piece of paper with the words of his favorite poem, “Lockesley Hall,” by Alfred Lord Tennyson:

Till the war-drum throbbed no longer, and the battle-flags were furl’d/In the Parliament of Man, the Federation of the World./There the common sense of most shall hold a fretful realm in awe/And the kindly earth shall slumber, lapt in universal law.

Just two weeks after Truman assumed the presidency, a conference was held in San Francisco to discuss forming a new global organization. To create this organization, the Truman administration had to overcome the reservations of wartime allies like Winston Churchill and the anxieties of smaller countries. For nine weeks, the delegates debated which countries should be admitted to membership and how much authority the great powers should have.

The resulting UN Charter was, like the U.S. Constitution, the product of compromise. The Charter sought, first of all, to balance state sovereignty (that is, the independence of individual nations) with a multinational, collective approach to global problems. The Charter also sought to recognize the dominant influence of the great powers while ensuring an important role for smaller countries.

Today, the UN consists of the Secretariat, the UN’s administrative leadership; the General Assembly, in which most nations of the world are represented, each, regardless of size, with one vote; a Security Council, where five permanent members can exercise veto power; an International Court of Justice; plus a series of other organs and largely autonomous agencies (such as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the UN Children’s Fund, and the World Health Organization).

The UN is quite a different organization than it was at its founding. The UN’s membership nearly tripled from 51 members in 1945 to 144 in 1975 and reached 193 in 2017.

Americans have long had a love-hate relationship with the United Nations—even though the organization itself was largely a product of American values and design and its headquarters is located in New York City. There are those who complain about the UN’s large bureaucracy, its cost, its deep political divisions, and its lack of effective central coordination. Many focus on the organization’s failure to prevent war, genocide, and ethnic cleansing.

Many of the UN’s weaknesses stem, ultimately, from the fact that we inhabit a world in which countries, great powers and smaller states alike, tend to act unilaterally to advance their national interests. When the UN Security Council’s permanent members are united, they can levy sanctions, wage war, impose blockades, and redraw borders. But most of the time, the permanent members have diverging interests. This makes it difficult for the UN to address the host of challenges facing the world today (which include global warming, terrorism, refugees, and nuclear proliferation).

The United Nations is often attacked for being weak and ineffectual and dependent on the whims of powerful national governments. Its supporters argue that, for all its weaknesses, the United Nations remains a vital instrument in maintaining international order, advancing human rights, assisting refugees, and promoting economic prosperity. It supports peacekeeping, human rights, economic development, and cultural advancement.