The War in the Pacific

The War in the Pacific

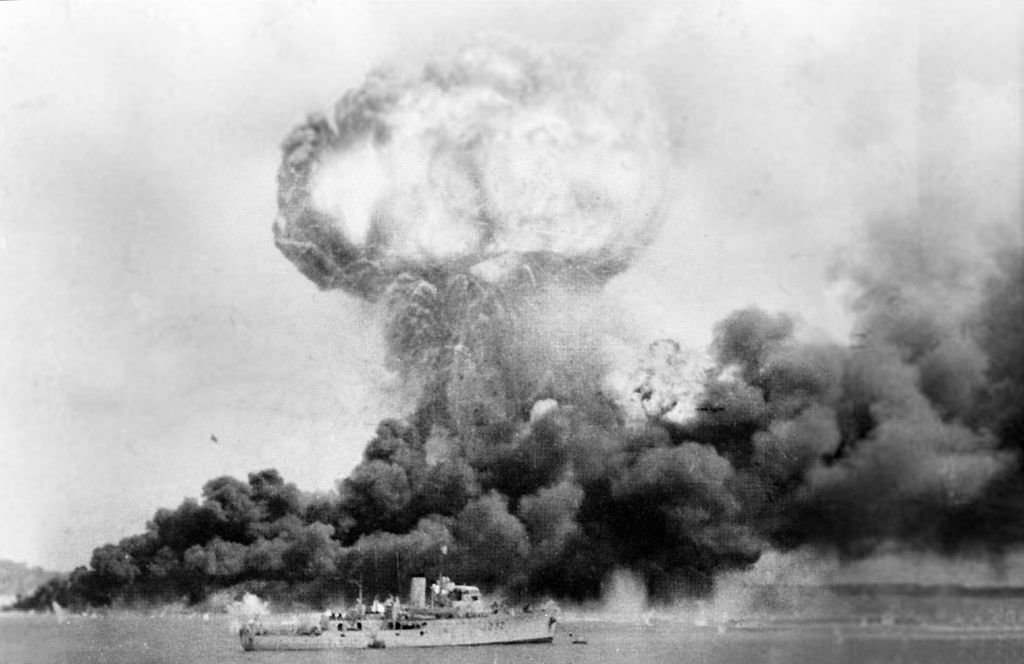

On December 7, 1941, Japan had launched an offensive incredible in its scale. A thousand Japanese warships attacked an area comprising one-third of the earth’s surface, including Guam, Hong Kong, Malaya, Midway Island, the Philippine Islands, and Wake Island. The offensive was a stunning success. Hong Kong was overrun in eighteen days, Wake Island in two weeks, Singapore held out for two months. By May, the Japanese had also captured the islands of Borneo, Bali, Sumatra, and Timor. In addition, Japan had taken Rangoon, Burma’s main port, and seized control of the rich tin, oil, and rubber resources of Southeast Asia.

By mid-summer of 1942, however, American forces had halted the Japanese advance. In May, a Japanese troop convoy was intercepted and destroyed by the U.S. Navy at Coral Sea, preventing a Japanese attack on Australia. In early June, at Midway Island in the Central Pacific, the Japanese launched an aircraft carrier offensive to cut American communications and to isolate Hawaii to the east. In a three-day naval battle, the Japanese lost three destroyers, a heavy cruiser, and four carriers. The Battle of Midway broke the back of Japan’s navy.

To defeat Japan, Allied forces pursued two strategies. General Douglas MacArthur pushed northward from Australia through New Guinea and from the Philippines towards Japan. Meanwhile, Admiral Chester Nimitz advanced on Japan by attacking Japanese-held islands in the Central Pacific in a leap-frog fashion—invading strategic islands and bypassing others. By late 1944, the United States was able to bomb the Japanese islands.

The Dawn of the Atomic Age

In 1939, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to President Roosevelt, warning him that the Nazis might be able to build an atomic bomb. On December 2, 1942, Enrico Fermi, an Italian refugee, produced the first self-sustained, controlled nuclear chain reaction in Chicago.

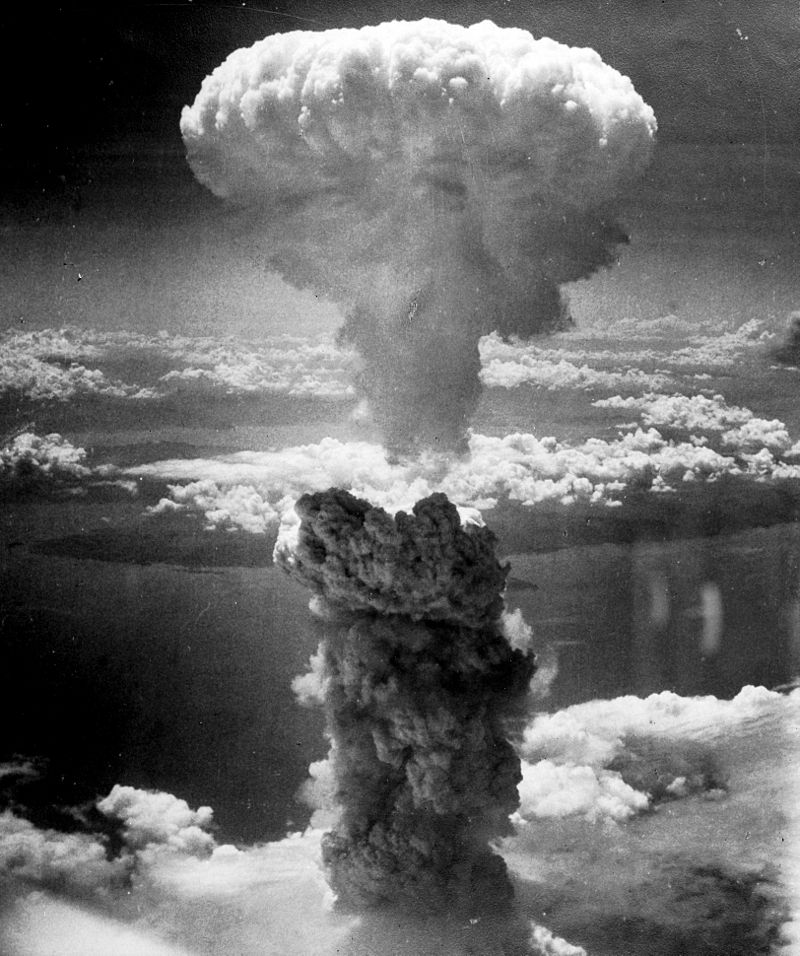

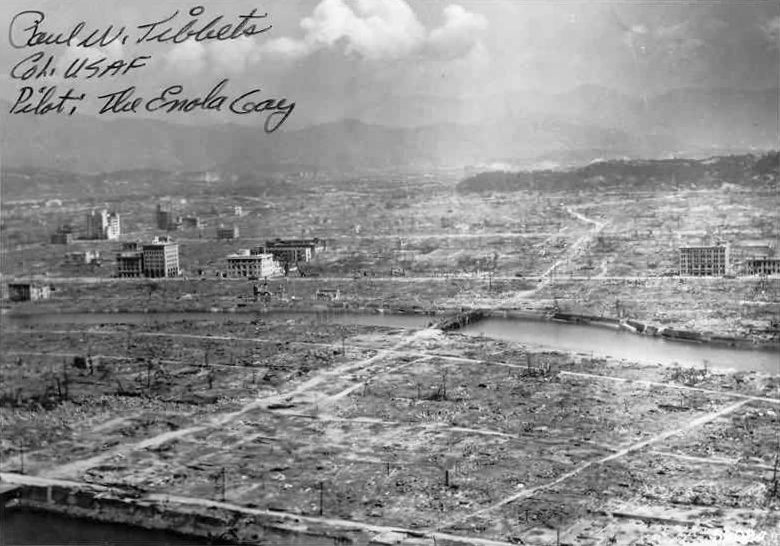

To ensure that the United States developed a bomb before Nazi Germany did, the federal government started the secret $2 billion Manhattan Project. On July 16, 1945, in the New Mexico desert near Alamogordo, the Manhattan Project’s scientists exploded the first atomic bomb. On August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay, a B-29 Superfortress, released an atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Japan. Between 80,000 and 140,000 people were killed or fatally wounded. Three days later, a second bomb fell on Nagasaki. About 35,000 people were killed. The following day Japan sued for peace.

President Truman’s defenders argued that the bombs ended the war quickly, avoiding the necessity of a costly invasion and the probable loss of tens of thousands of American lives and hundreds of thousands of Japanese lives. His critics argued that the war might have ended even without the atomic bombings. They maintained that the Japanese economy would have been strangled by a continued naval blockade, and that Japan could have been forced to surrender by conventional firebombing or by a demonstration of the atomic bomb’s power.

The unleashing of nuclear power during World War II generated hope of a cheap and abundant source of energy, but it also produced anxiety among large numbers of people in the United States and around the world.

President Truman: Using Atomic Bombs against Japan, 1945

Every American president makes decisions with enormous repercussions for the future. Some of these decisions prove successful; others turn out to be blunders. In virtually every case, presidents must act with contradictory advice and limited information.

At 8:15 a.m., August 6, 1945, an American B-29 released an atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Japan. Within minutes, Japan’s eighth largest city was destroyed. By the end of the year, 140,000 people had died from the bomb’s effects. After the bombing was completed, the United States announced that Japan faced a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which had never been seen on this earth.”

Background: In 1939, Albert Einstein, writing on behalf physicist Leo Szilard and other leading physicists, informed President Franklin D. Roosevelt that Nazi Germany was carrying on experiments in the use of atomic weapons. In October, 1939, the federal government began a modest research program which and later became the two-billion-dollar Manhattan Project. Its purpose was to produce an atomic bomb before the Germans. On December 2, 1942, scientists in Chicago succeeded in starting a nuclear chain reaction, demonstrating the possibility of unleashing atomic power.

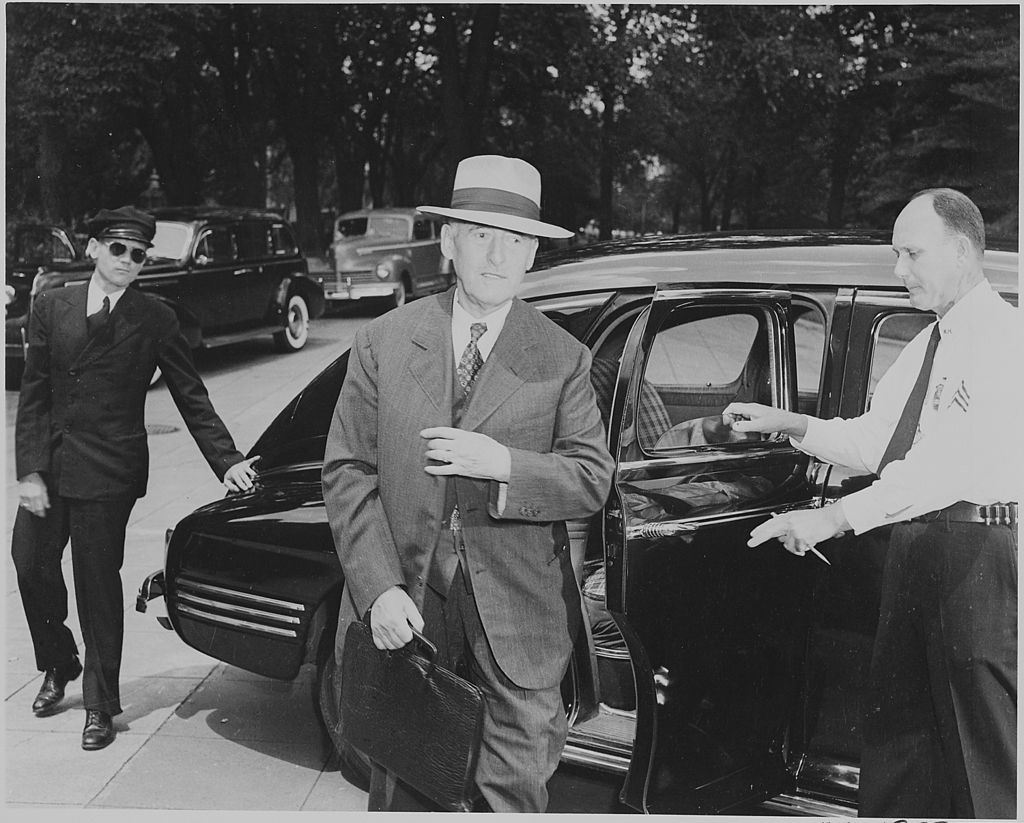

It was not until April 25, 1945, 13 days after the death of Franklin Roosevelt, that the new president, Harry S. Truman, was briefed about the Manhattan Project. Secretary of War Henry Stimson informed him that “within four months we shall in all probability have completed the most terrible weapon ever known in human history.”

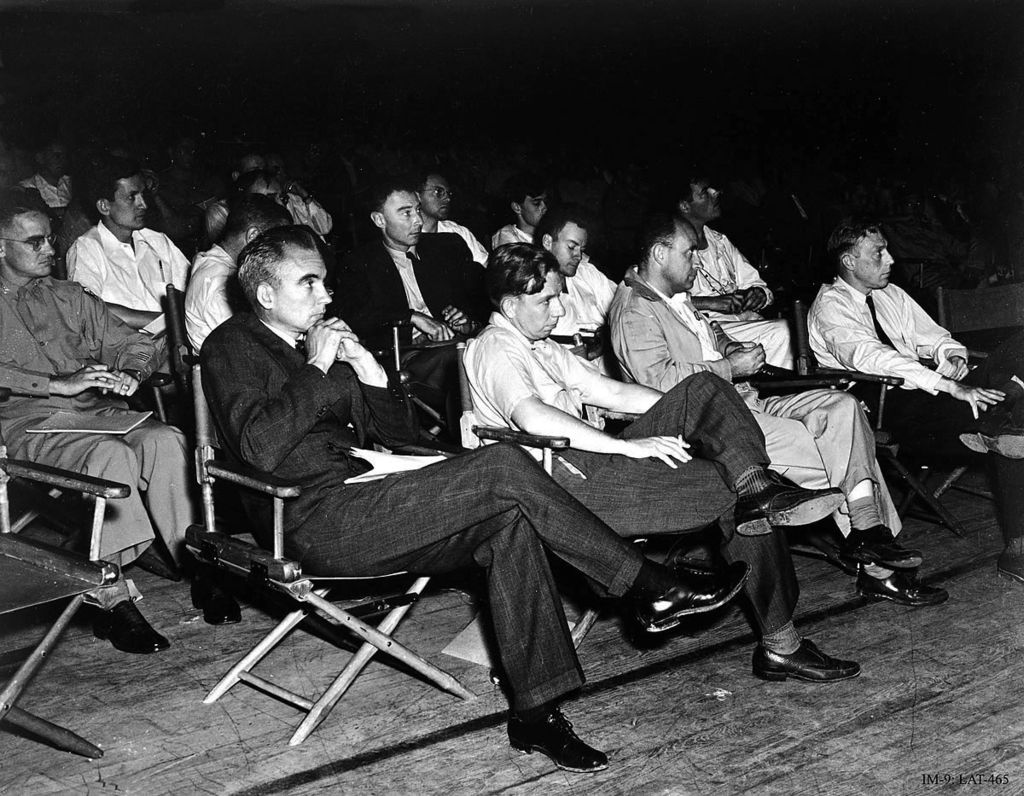

Stimson proposed that a special committee be set up to consider whether the atomic bomb would be used, and if so, when and where it would be deployed. Members of this panel, known as the Interim Committee, which Stimson chaired, included George L. Harrison, President of the New York Life Insurance Company and special consultant in the Secretary’s office; James F. Byrnes, President Truman’s personal representative; Ralph A. Bard, Under Secretary of the Navy; William L. Clayton, Assistant Secretary of State; and scientific advisers Vannevar Bush, Karl T. Compton, and James B. Conant. General George Marshall and Manhattan Project Director Leslie Groves also participated in some of the committee’s meetings.

On June 1, 1945, the Interim Committee recommended that that atomic bombs should be dropped on military targets in Japan as soon as possible and without warning. One committee member, Ralph Bard, convinced that Japan may be seeking a way to end the war, called for a two to three-day warning before the bomb was dropped.

A group of scientists involved in the Manhattan project opposed the use of the atomic bomb as a military weapon. In a report signed by physicist James Franck, they called for a public demonstration of the weapon in a desert or on a barren island. On June 16, 1945, a scientific panel consisting of physicists Arthur H. Compton, Enrico Fermi, E. O. Lawrence, and J. Robert Oppenheimer reported that it did not believe that a technical demonstration would be sufficient to end the war.

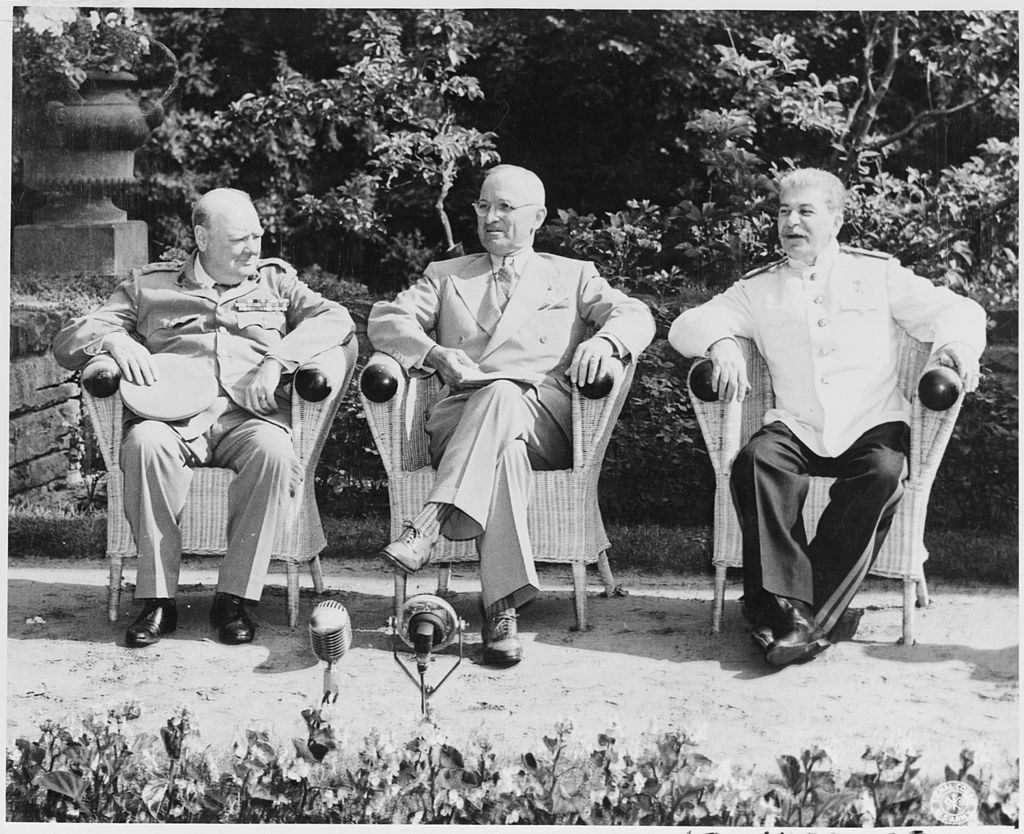

Meanwhile, after a June 18, 1945, meeting with his military advisors, President Truman approved a plan that called for an initial invasion of Japan on November 1. By the summer of 1945, a growing number of government policy makers were concerned about Soviet intervention in the war against Japan. Already, the Red Army occupied Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary. At the Potsdam conference in July, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin informed President Truman and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill that the Red Army would enter the war against Japan around August 8.

On July 25, 1945, the military was authorized to drop the bomb as soon as weather will permit visual bombing after about 3 August 1945 on one of the targets: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata and Nagasaki.

The bombing of Hiroshima, followed by the Soviet declaration of war against Japan on August 9th and the bombing of Nagasaki the same day, led the Japanese leadership to accept a surrender so long as their country could retain the emperor.

Variety of points of view:

Ralph Bard, Under Secretary of the Navy: “Ever since I have been in touch with this program I have had a feeling that before the bomb is actually used against Japan that Japan should have some preliminary warning for say two or three days in advance of use. The position of the United States as a great humanitarian nation and the fair play attitude of our people generally is responsible in the main for this feeling.”

James Byrnes: [Physicist Leo Szilard wrote:] “[Byrnes] was concerned about Russia’s postwar behavior. Russian troops had moved into Hungary and Romania, and Byrnes thought it would be very difficult to persuade Russia to withdraw her troops from these countries, that Russia might be more manageable if impressed by American military might, and that a demonstration of the bomb might impress Russia.”

General Dwight D. Eisenhower: “In 1945 …, Secretary of War Stimson visited my headquarters in Germany, [and] informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act…. During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and second because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face.’

Admiral William Leahy told President Truman: “This is the biggest fool thing we have ever done. The bomb will never go off, and I speak as an expert in explosives.”

Controversy Continues

Fifty years after the United States ended World War II by dropping two atomic bombs on Japan, a major public controversy erupted over plans to exhibit the fuselage of the Enola Gay at the Smithsonian Institution’s Air and Space Museum. As originally conceived, the exhibit, titled “The Last Act: The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II,” was designed to provoke debate about the decision to drop atomic bombs. Museum visitors would be encouraged to reflect on the morality of the bombing and to ask whether the bombs were necessary to end the war.

The proposal generated a firestorm of controversy. The part of the script that produced the most opposition stated: “For most Americans, this…was a war of vengeance. For most Japanese, it was a war to defend their unique culture against Western imperialism.” Another controversial section addressed the question: “Would the bomb have been dropped on the Germans?” The answer began: “Some have argued that the United States would never have dropped the bomb on the Germans, because Americans were more reluctant to bomb ‘white people’ than Asians.”

Veterans groups considered the proposed exhibit too sympathetic to the Japanese, portraying them as victims of racist Americans hell-bent on revenge for Pearl Harbor. They called the exhibit an insult to the U.S. soldiers who fought and died during the war and complained that it paid excessive attention to Japanese casualties and suffering and paid insufficient attention to Japanese aggression and atrocities. The U.S. Senate unanimously passed a resolution calling a revised version of the exhibit “unbalanced and offensive” and reminding the museum of “its obligation to portray history in the proper context of its time.”

In the end, the Smithsonian decided to scale back the exhibit, displaying the Enola Gay’s fuselage along with a small plaque. In announcing the decision, a Smithsonian official explained, “In this important anniversary year, veterans and their families were expecting, and rightly so, that the nation would honor and commemorate their valor and sacrifice. They were not looking for analysis and, frankly, we did not give enough thought to the intense feelings such an analysis would evoke.”

The decision to use atomic bombs against Japan was the most controversial decision in military history.

Early in 1946, the Federal Council of Churches called the bombings “morally indefensible” because Japan had received no specific advancing warning. In July, the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey concluded that Japan would have surrendered “certainly prior to December 31, 1945, and in all probability prior to November 1, 1945…even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion [of Japan] had been planned or contemplated.” The bombing survey assumed that the firebombing of Japanese cities would have continued. An account of six survivors of the Hiroshima bombing by John Hersey published in the New Yorker magazine in August 1946, which helped to humanize the bomb’s victims, led the influential magazine Saturday Review to describe the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a crime.

Henry Stimson, the 78-year-old former secretary of war, publicly defended the U.S. decision to drop the bombs. He argued that the Japanese were determined to fight to the death and that, without the bombings, it would have cost at least a million American and many more Japanese causalities to achieve victory. Stimson also explained why the U.S. had refused to warn Japan about the new weapon or to stage a demonstration of the bomb’s destructive power. Engineers were unable to assure the government that the bombs would work, and officials feared that a failure would have disastrous effects on American morale. Further, they noted that even if a successful demonstration was carried out, the Japanese government might suppress the news.

In 1949, Stimson’s arguments were challenged by a British physicist, P.M.S. Blackett. Blackett claimed that the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was intended, at least in part, to intimidate the Soviet Union.

Why did the United States drop the bomb when it did? On July 29, a U.S. Navy ship, the Indianapolis, was sunk and 883 lives were lost. A U.S. invasion of Southeast Asia was scheduled for September 6, in which case, it was likely that 100,000 British, Dutch, and American Prisoners of War would be executed by the Japanese.

Decrypted Japanese military cables indicated that Japan was building-up its defenses in preparation for an American invasion, and many Japanese leaders testified that they were confident that they could have stopped at least the first wave of an American invasion. Decoded diplomatic cables indicated that Japan’s leaders were seeking to persuade the Soviet Union to negotiate an armistice on favorable terms that would have allowed Japan to retain conquered territory. A three-time Japanese premier, Prince Konoye Fumimaro, said that had the atomic bombs not been dropped, the war would have continued into 1946: “The army had dug themselves caves in the mountains and their idea of fighting on was fighting from every little hole or rock in the mountains.”