The League of Nations

The Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations

The treaty ending World War I failed to fulfill President Woodrow Wilson’s dream of a “peace without victory.” Instead, it in many respects lived up to his worst fears. “Victory would mean peace forced upon the loser,…. It would be accepted in humiliation…and would leave a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest, not permanently, but only as upon quicksand.”

The Treaty of Versailles altered the balance of power in Europe. It explicitly blamed Germany for the outbreak of the war and forced it to pay substantial financial reparations. The treaty also forced Germany to disarm and to give up substantial amounts of territory to France and to newly independent Czechoslovakia and Poland, placing 7 million German-speakers outside of Germany itself. In addition, the treaty required Germany to transfer its African colonies to France, Belgium, Portugal, and Britain

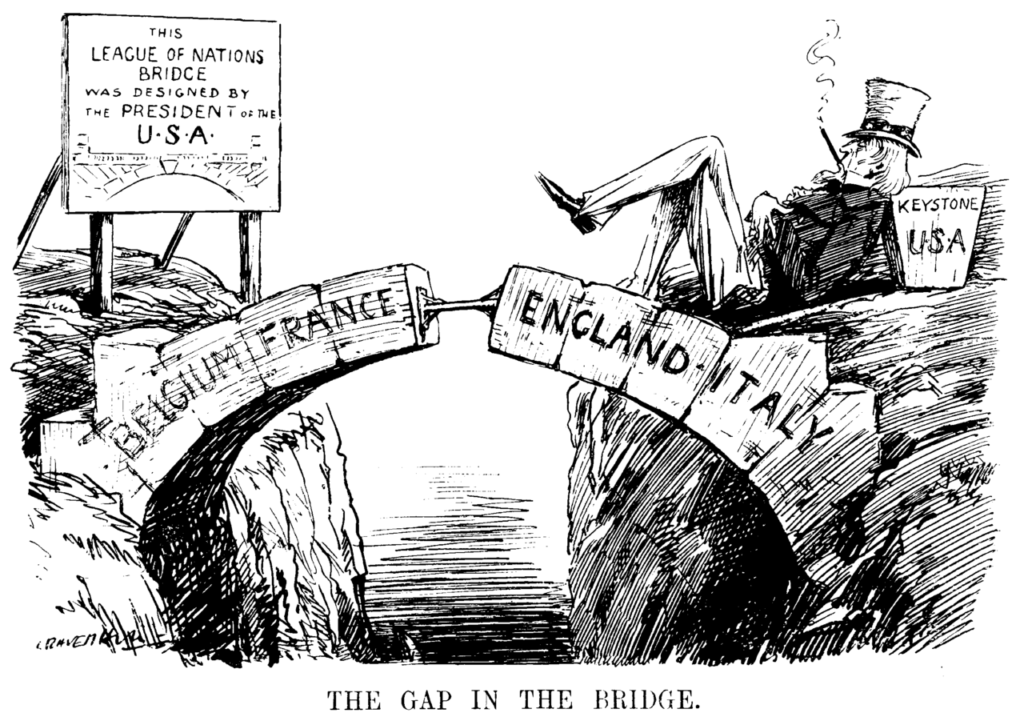

In one respect, the treaty did live up to President Wilson’s vision: An international League of Nations was established, dedicated to preventing war through disarmament, arbitration and a system of collective security guarantees.

The United States, however, refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, ending the war, and rejected President Wilson’s call to join the League of Nations. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Massachusetts), chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee and the majority leader of the upper chamber, sent the treaty to the Senate floor. Lodge included 14 “reservations,” that curbed the League’s influence over any future U.S. decision making. The most pointed opposition was to Article Ten of the League Charter, which committed member states to protect the territorial integrity of all other member states against external aggression. After Wilson asked his supporters to oppose Lodge’s proposed caveats, the Senate divided 55-39, falling short of the two-thirds majority needed for ratification.

The Senate reconsidered the treaty once more, with reservations, on March 19, 1920. That vote, 49-35, fell seven votes short of the required two-thirds majority. In 1921, Congress passed the Knox-Porter Resolution, formally ending the war with Germany.

Wilson’s refusal to compromise with the Republican opposition led the Senate to vote against joining the League of Nations. It left Wilson with a reputation as a stubborn, cold, rigidly self-righteous, and naïve leader who failed to deal realistically with the harsh realities of the world.

A serious problem for the League was the withdrawal of many nations from the organization, beginning with Costa Rica in 1923. At its height, the organization had 58 members, but as smaller nations such as Guatemala and El Salvador and larger nations including Germany, Italy, and Japan withdrew, the League was left with just 34 member states at the time of its demise in 1947.

Yet while Wilson died in 1924 embittered and defeated, his principles of collective security, national self-determination, and international law, would live on in the United Nations.

When historians rank presidents, Woodrow Wilson is almost always placed in the Top 10. In less than two years, he established the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Reserve while reforming trust, tariff, and tax law. As part of a regional strategy to preempt German influence, Wilson sent American troops to occupy Haiti in 1915 and the Dominican Republic in 1916, and a year later the United States bought the Virgin Islands, thereby gaining control of every major Caribbean island except British Jamaica.

On the other hand, his record on issues of race and civil liberties and his crackdown on political dissidents has soured his reputation.

It is in international affairs that Wilson’s influence is most palpable. Wilson asked that the country fight to make the world “safe for democracy.” He defined the war not simply as a conflict among nations but as an effort to fight for “the principles of a liberated mankind.”

In recent years, the word “Wilsonian” is sometimes used as an epithet to describe a naïve, utopian effort to create a “new world order,” end war, and spread democracy throughout the world. But his emphasis on international law, human rights, and collective security continues to influence American foreign policy even today.

World War I Inevitable or an Accident?

The question of whether World War I was inevitable or an accident that statesmen stumbled into is a question that has been debated for a century.

Those who argue that the war was inevitable make the following points:

- Rising nationalism and an escalating arms race among the European powers.

- A newly ascendant Germany wanted “a place in the sun” and feared encirclement by Russia, Britain, and France.

- The weakening of the Ottoman Empire caused conflict through the Balkans and led Russia, Britain, France, and Germany to covet such possessions as Armenia, Syria, and Iraq.

- Secret mutual defense treaties allowed a minor dispute to turn into a major conflagration. No one in Britain told Germany that its support for Austria-Hungary would result in war.

- The European powers, facing growing challenges from socialists and the working class, embraced nationalism and militarism as a way to detract attention from problems on the home front.

- Elaborate war plans involving the mobilization of thousands of troops, trains, and horses made it impossible to stop the cycle of escalation. When one country mobilized, its adversaries did the same.

Those who argue that the war was not inevitable and was the result of a series of blunders and accidents make these points:

- No leader wanted war in 1914. The three principal monarchs of the age, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany; King George V of England; and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia were cousins.

- Trade bound the major powers together. Germany and Britain were each other’s largest trading partners.

- Previous assassinations of European leaders had not resulted in war. There was nothing inevitable about an assassination sparking a conflict in 1914.

- There was plenty of time even after the assassination to achieve a peaceful solution to the tension. The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria took place June 28, 1914. The war didn’t begin until July 28th. Negotiations could have ended the conflict at any time during that month-long period. But a lack of clear communication allowed the crisis to escalate.

- Poor leadership intensified the crisis. France egged on Russia against Austria-Hungary and Germany, while Britain failed to mediate the mounting conflict as it had done in the past, allowing events to spin out of control.