WWI on the Home Front

Over Here: World War I on the Home Front

When the U.S. entered World War I, approximately one-third of the nation (32 million people) were either foreign-born or the children of immigrants, and more than ten million Americans were derived from the nations of the Central Powers. Furthermore, millions of Irish Americans sided with the Central Powers because they hated the English.

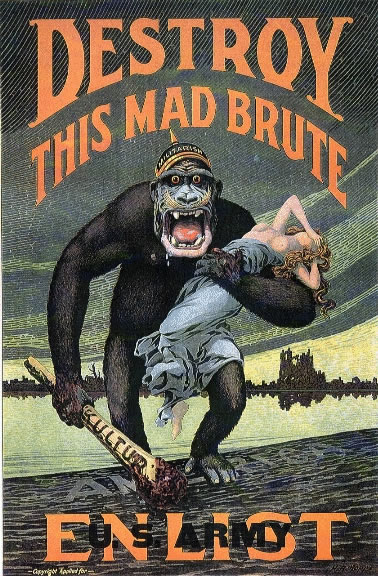

Because of this perceived conflict of loyalties, the Wilson administration was convinced that it had to mobilize public opinion in support of the war. To influence public opinion, the federal government embarked on its first ever domestic propaganda campaign. Wilson chose muckraking journalist George Creel to head the government agency, the Committee on Public Information (CPI). The CPI placed pro-war advertisements in magazines and distributed 75 million copies of pamphlets defending America’s role in the war. Creel also launched a massive advertising campaign for war bonds and sent some 75,000 “Four-Minute Men” to whip up enthusiasm for the war by rallying audiences in theaters. The CPI also encouraged filmmakers to produce movies, like The Kaiser: The Beast of Berlin, that played up alleged German atrocities. For the first time, the federal government had demonstrated the power of propaganda.

Anti-German Sentiment

German American and Irish American communities had come out strongly in favor of neutrality. The groups condemned massive loans and arms sales to the allies as violations of American neutrality. Theodore Roosevelt raised the issue of whether these communities were loyal to their mother country or to the United States:

Those hyphenated Americans who terrorize American politicians by threats of the foreign vote are engaged in treason to the American Republic.

Once the United States entered the war, a search for spies and saboteurs escalated into efforts to suppress German culture. Many German-language newspapers were closed down. Public schools stopped teaching German. Lutheran churches dropped services that were spoken in German.

Germans were called “Huns.” In the name of patriotism, musicians no longer played Bach and Beethoven, and schools stopped teaching the German language. Americans renamed sauerkraut “liberty cabbage,” dachshunds “liberty hounds,” and German measles “liberty measles.” Cincinnati, with its large German American population, even removed pretzels from the free lunch counters in saloons. More alarming, vigilante groups attacked anyone suspected of being unpatriotic. Workers who refused to buy war bonds often suffered harsh retribution, and attacks on labor protesters were nothing short of brutal. The legal system backed the suppression. Juries routinely released defendants accused of violence against individuals or groups critical of the war.

A St. Louis newspaper campaigned to “wipe out everything German in this city,” even though St. Louis had a large German American population. Luxembourg, Missouri became Lemay; Berlin Avenue was renamed Pershing, Bismarck Street became Fourth Street, Kaiser Street was changed to Gresham.

Perhaps the most horrendous anti-German act was the lynching in April 1918 of 29-year-old Robert Paul Prager, a German-born bakery employee, who was accused of making “disloyal utterances.” A mob took him from the basement of the Collinsville, Illinois jail, dragged him outside of town, and hanged him from a tree. Before the lynching, he was allowed to write a last note to his parents in Dresden, Germany: “Dear Parents: I must on this, the 4th day of April, 1918, die. Please pray for me, my dear parents.”

In the trial that followed, the defendants wore red, white, and blue ribbons, while a band in the court house played patriotic songs. It took the jury twenty-five minutes to return a not-guilty verdict. The German government lodged a protest and offered to pay Prager’s funeral expenses.

More Americans are of German descent than from any other nationality group. Altogether, about seventeen percent of Americans are solely or partially of German descent.

Yet despite the fact that Germans are the U.S.’s largest ethnic minority, German ethnicity is far less visible than that among Greeks, Irish, Italians, Mexicans, or Puerto Ricans. German foods and traditions—hot dogs, hamburgers, beer, cole slaw, pretzels, and Christmas trees, among others—permeate American culture, but the German presence is not particularly noticeable. World War I played a crucial role in rendering German Americans a largely invisible minority.

The Espionage and Sedition Acts

In his war message to Congress, President Wilson had warned that the war would require a redefinition of national loyalty. There were “millions of men and women of German birth and native sympathy who live amongst us,” he said. “If there should be disloyalty, it will be dealt with a firm hand of repression.”

In June 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act. This piece of legislation gave postal officials the authority to ban newspapers and magazines from the mails and threatened individuals convicted of obstructing the draft with $10,000 fines and twenty years in jail. Congress passed the Sedition Act of 1918, which made it a federal offense to use “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the Constitution, the government, the American uniform, or the flag. The government prosecuted over 2,100 people under these acts.

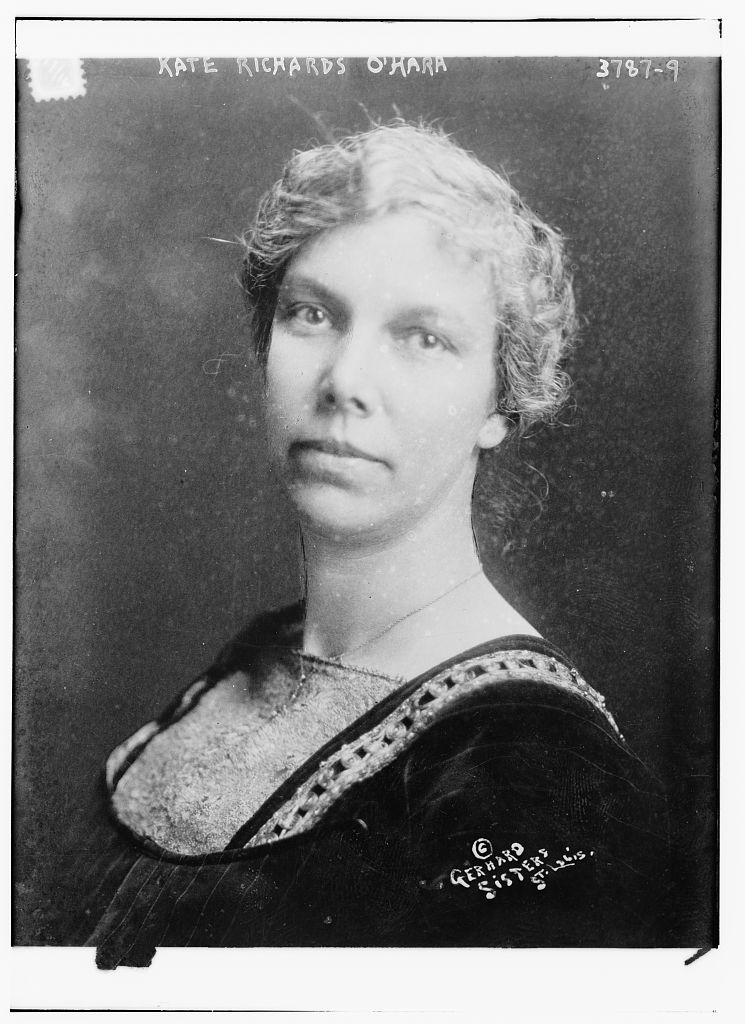

Political dissenters bore the brunt of the repression. Eugene V. Debs, who urged socialists to resist militarism, went to prison for nearly three years. Another Socialist, Kate Richards O’Hare, served a year in prison for stating that the women of the United States were “nothing more nor less than brood sows, to raise children to get into the army and be made into fertilizer.”

In July 1917, labor radicals offered another ready target for attack. In Cochise County, Arizona, armed men, under the direction of a local sheriff, rounded up 1,186 strikers at the Phelps Dodge copper mine. They placed these workers—many of Mexican descent—on railroad cattle cars without food or water and left them in the New Mexico desert 180 miles away. The Los Angeles Times editorialized: “The citizens of Cochise County have written a lesson that the whole of America would do well to copy.”

The radical labor organization, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), never recovered from government attacks during World War I. In September 1917, the Justice Department staged massive raids on IWW officers, arresting 169 of its veteran leaders. The administration’s purpose was, as one attorney put it, “very largely to put the IWW out of business.” Many observers thought the judicial system would protect dissenters, but the courts handed down stiff prison sentences to the radical labor organization’s leaders.

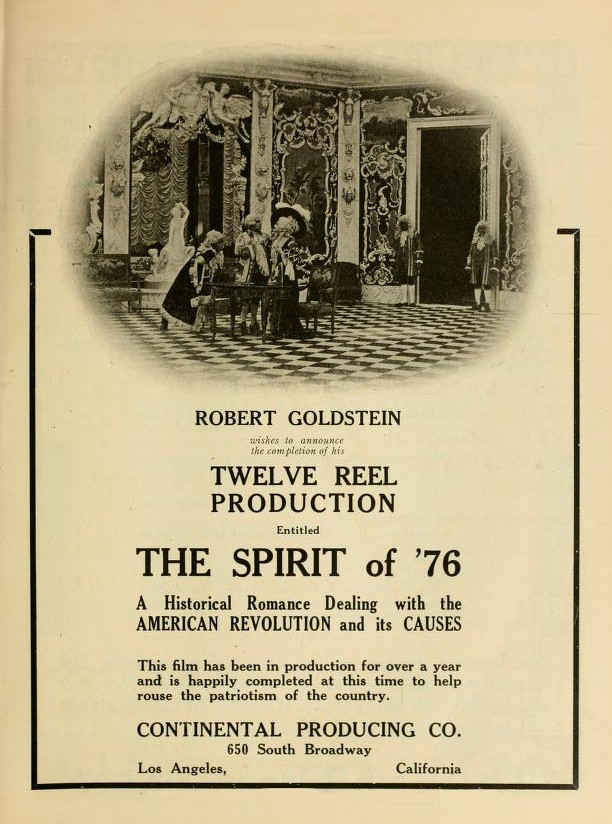

Radicals were not the only one to suffer harassment. Robert Goldstein, a motion picture producer, had made a movie about the American Revolution called The Spirit of ’76, before the United States entered the war. When he released the picture after the declaration of war, he was accused of undermining American morale. A judge told him that his depiction of heartless British redcoats caused Americans to question their British allies. He was sentenced to a ten-year prison term and fined $5,000.

During World War, the US government initiate unprecedented efforts to restrict unpatriotic speech. More than 2,000 people were prosecuted under the Espionage and Sedition Acts and about half were convicted.

The Espionage Act made it a crime to convey false information that would interfere with the American military, or promote the success of America’s enemies. It also criminalized any attempts to cause insubordination within the military or willfully obstruct military recruitment or enlistment. The Sedition Act went further, making it illegal to use disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive speech about the United States or its symbols, to speak in a way that might impede war production, or support a country with which the U.S. was at war.

In fact, the restrictions imposed on freedom of speech and the press during World War I and the legal cases that challenged them gave rise to the modern conception of the First Amendment as a guarantee of free speech and press freedom.

Music of World War I

Many of Americans’ favorite songs achieved their popularity in wartime, such as “Yankee Doodle” during the Revolution or “Battle Cry of Freedom” during the Civil War. But in no war was music more pervasive than during World War I. The commercial music industry immediately went to work, producing songs for a mass audience.

There were antiwar songs, like “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to be a Soldier.” There were morale boosters, like George M. Cohan’s “Over There.” There were also comic songs, like Irving Berlin’s “I Hate to Get Up in the Morning.” Many songs dealt with separation and loss, like “Keep the Home Fires Burning.” Some songs speculated about the war’s longterm impact, like “How Ya Gonna Keep ‘Em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen Paree).”