The U.S. Enters the War

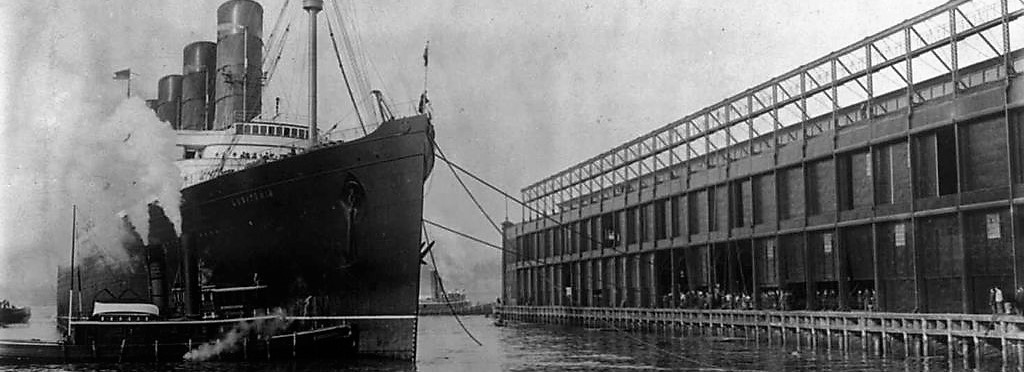

The Lusitania

On May 7, 1915, the Lusitania, the “fastest vessel afloat,” was sunk by a torpedo from a German submarine. The ship sank off the Irish coast in under twenty minutes. A total of 1,198 passengers and crew members lost their lives; only 861 people survived.

The German Embassy had issued a warning that appeared in New York newspapers:

Travelers intended to embark for an Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies…. Vessels flying the flag of Great Britain or any of her allies are liable to destruction.

The Lusitania had previously made a half dozen Atlantic round trips without incident. Few believed that a civilian passenger ship would be deliberately targeted.

Following the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, Germany would institute a moratorium on unrestricted submarine warfare. However, pressure on the German high command to resume unrestricted submarine warfare was great. It was viewed as the only way to starve Britain and France into submission. This resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare would ultimately bring the United States into the war.

The United States Enters the War

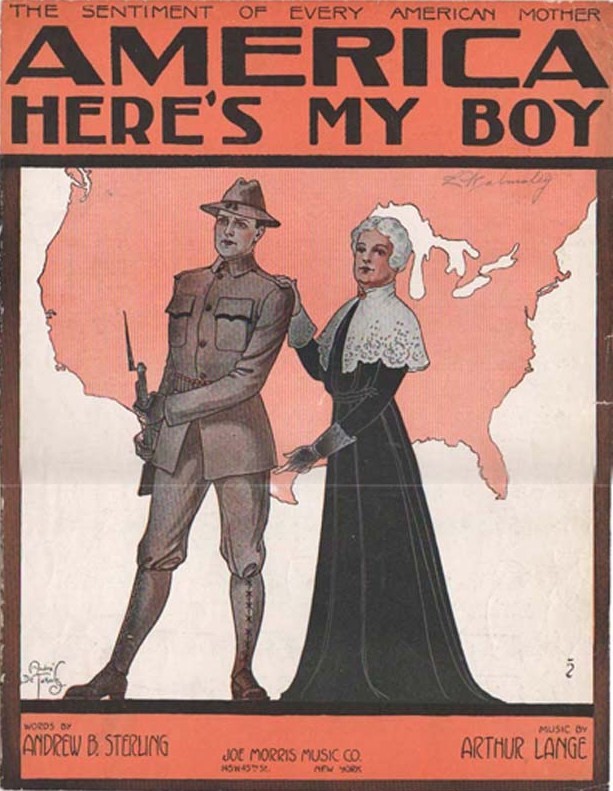

President Wilson was reluctant to enter World War I. When the war began, Wilson declared U.S. neutrality and demanded that the belligerents respect American rights as a neutral party. He hesitated to embroil the United States in the conflict, with good reason. Americans were deeply divided about the European war, and involvement in the conflict would certainly disrupt Progressive reforms. In 1914, he had warned that entry into the conflict would bring an end to Progressive reform. “Every reform we have won will be lost if we go into this war,” he said. Public sentiment was, at least at first, significantly opposed to U.S. involvement in the conflict. A popular song in 1915 was “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier.”

In 1916, President Wilson narrowly won re-election after campaigning on the slogan, “He kept us out of war.” He won the election with a 4,000 vote margin in California.

Toward Intervention

Shortly after war erupted in Europe, President Wilson called on Americans to be “neutral in thought as well as deed.” The United States, however, quickly began to lean toward Britain and France.

Convinced that wartime trade was necessary to fuel the growth of the American economy, President Wilson refused to impose an embargo on trade with the belligerents. During the early years of the war, trade with the Allies tripled.

This volume of trade quickly exhausted the Allies’ cash reserves, forcing them to ask the United States for credit. In October 1915, President Wilson permitted loans to belligerents, a decision that greatly favored Britain and France. By 1917, American loans to the Allies had soared to $2.25 billion. Loans to Germany stood at a paltry $27 million.

In January 1917, Germany announced that it would resume unrestricted submarine warfare. This announcement helped precipitate American entry into the conflict. Germany hoped to win the war within five months, and was willing to risk antagonizing Wilson on the assumption that even if the United States declared war, it could not mobilize quickly enough to change the course of the conflict.

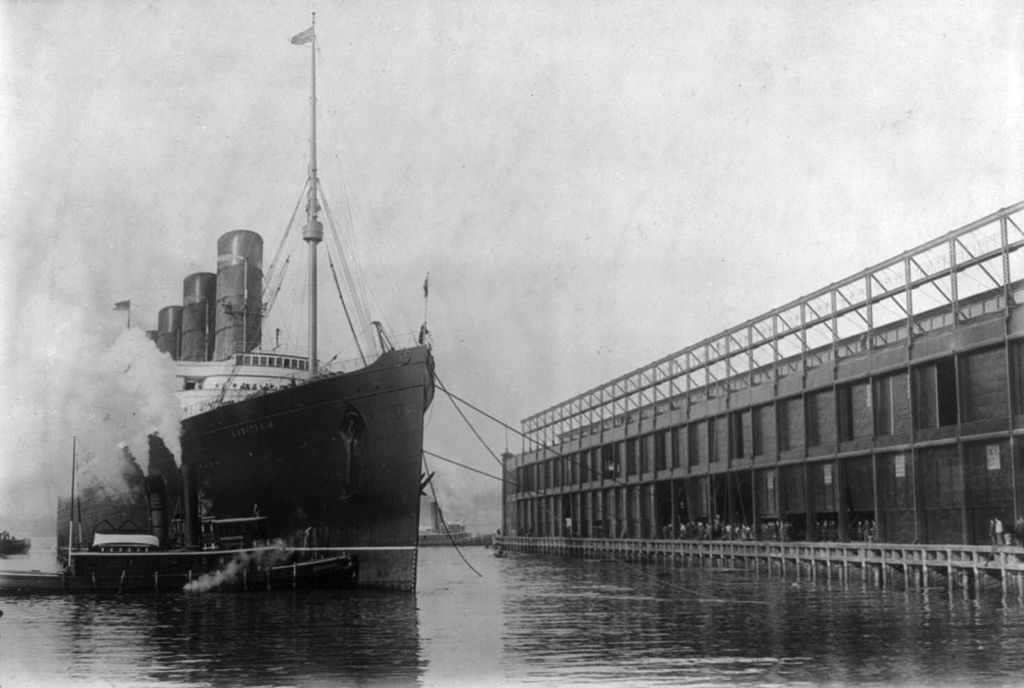

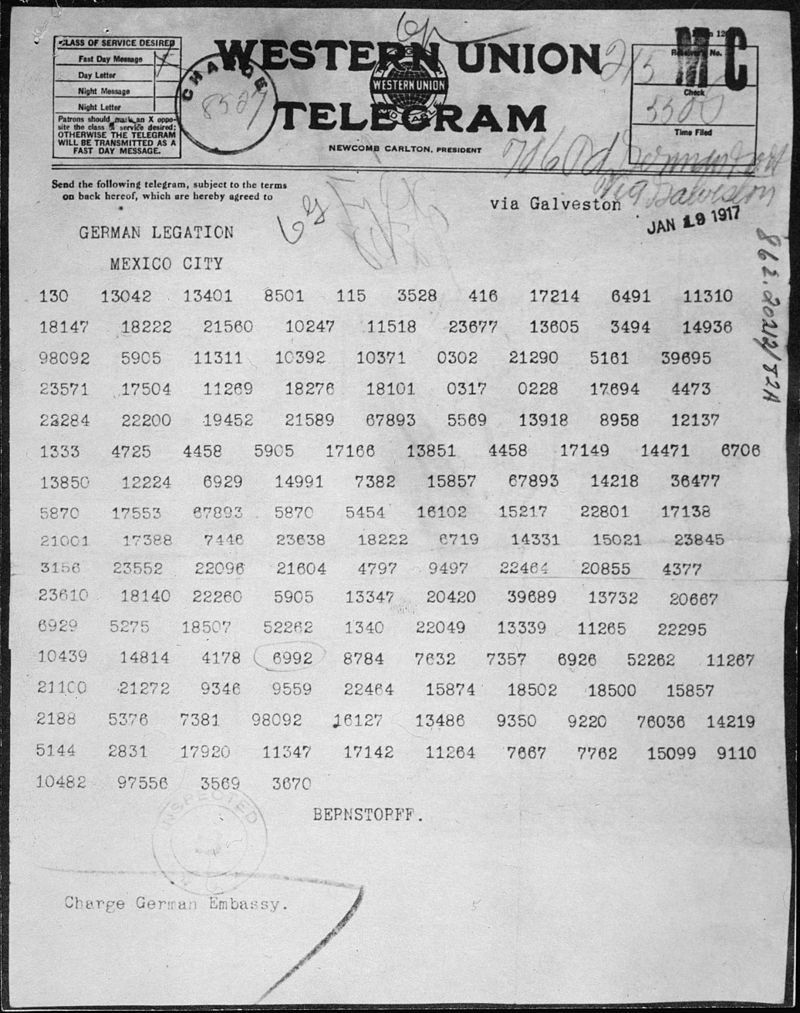

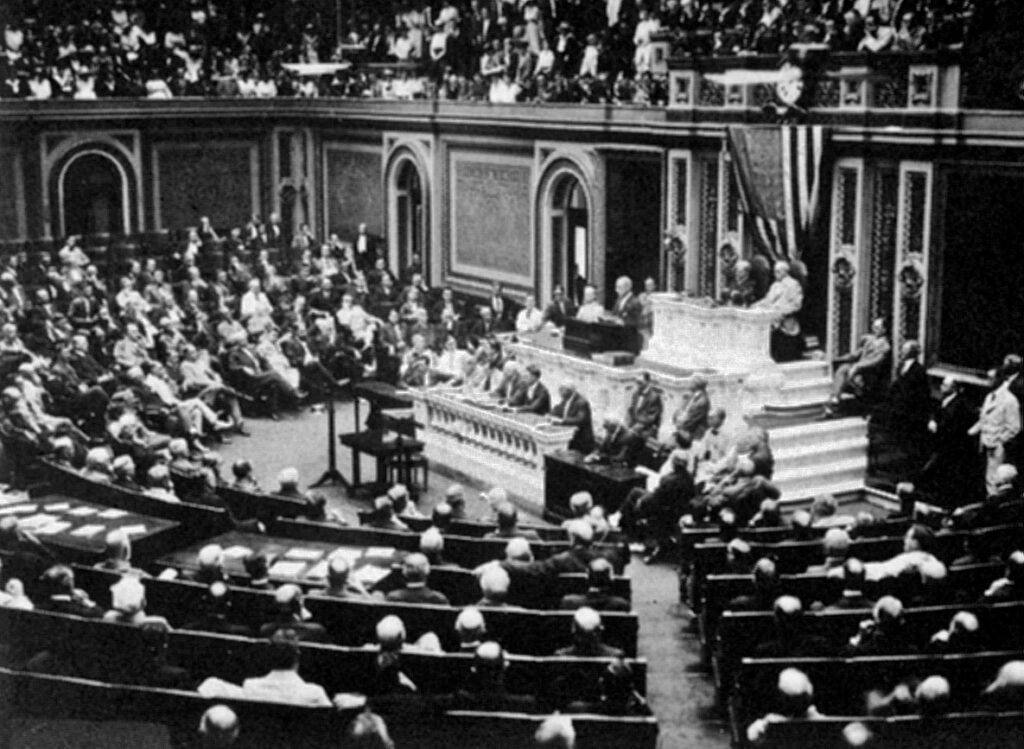

Then a fresh insult led Wilson to demand a declaration of war. In March 1917, newspapers published the Zimmermann Note, an intercepted telegram from the German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmerman to the German ambassador to Mexico. The telegram proposed that Mexico ally with Germany in the event that the United States entered the war against Germany. In return, Germany promised to help Mexico recover the territory it had lost to the U.S. during the 1840s, including Texas, New Mexico, California, and Arizona. The Zimmerman Note and German attacks on three U.S. ships in mid-March led Wilson to ask Congress for a declaration of war.

Wilson decided to enter the war so that he could help design the peace settlement. Wilson viewed the war as an opportunity to destroy German militarism. “The world must be made safe for democracy,” he told a joint session of Congress. Only six Senators and fifty Representatives voted against the war declaration.

14 Points

In January 1918, World War I was in its fourth year of stalemate. Russia, following the Communist Revolution, announced that it was withdrawing from the war.

President Woodrow Wilson chose this moment to present a proposal to end the conflict, indeed to head off future wars. The United States had entered the war nine months earlier.

Wilson’s Fourteen Points offered a framework for peace. He rejected the notion that diplomacy should be based on national self-interest. Instead, it should rest on the principles of international law and cooperation.

Wilson’s Fourteen Points rested upon seven principles:

- “Open covenants…openly arrived at”: In response to the cynical dealmaking and secret alliances, Wilson called for open diplomacy.

- “Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas”: Freedom of the shipping without restriction.

- “The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers”: Free trade and the elimination or reduction of protective tariffs.

- “National armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety.”: Arms reduction

- “In determining . . . questions of sovereignty, the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined.”: Respect for the sovereignty of the people.

- The right to national self-determination, that each national group should have its own state.

- An international body (that would be called the League of Nations) to maintain peace: A general association of nations…affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike. A league of nations to maintain peace.

The Fourteen points are often dismissed as idealistic, but unrealistic. Georges Clemenceau, France’s prime minister, who during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 supposedly mumbled, “God gave us his Ten Commandments, and we broke them. Wilson gave us his Fourteen Points – we shall see.”

Of all the ideas incorporated into the Fourteen Points, perhaps the most explosive was Wilson’s call for national self-determination. In a message to Congress he declared that “self-determination is not a mere phrase. It is an imperative principle of action which statesmen will henceforth ignore at their peril.”

His Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, worried that the call for national self-determination was “simply loaded with dynamite.” He wondered:

What effect will it have on the Irish, the Indians, the Egyptians, and the nationalists among the Boers? Will it not breed discontent, disorder, and rebellion?… How can it be harmonized with Zionism, to which the President is practically committed?

Lansing rejected Wilson’s idealistic vision as “the dream of an idealist who failed to realize the danger until too late. What a calamity that the phrase was ever uttered!” But the concept was enshrined in the first article of the United Nations Charter.

Making Ethical Judgements

Universal Self-Determination: A Good Idea?

At the height of World War I, Woodrow Wilson argued that self-determination for Europe’s myriad ethnic minorities, suddenly freed by the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires, would provide stability in the postwar environment. But even as the concept of self-determination was being born, President Wilson’s own Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, worried that the idea might make the world more dangerous.

“Will it not breed discontent, disorder and rebellion?” Lansing wrote. “The phrase is simply loaded with dynamite. It will raise hopes which can never be realized. It will, I fear, cost thousands of lives.”What a calamity that the phrase was ever uttered! What misery it will cause!”

Around 1776, there were about 35 empires, kingdoms, countries and states in the world. By World War II the number had doubled to roughly seventy. And that figure almost doubled again to more than 130 in the late 1960’s. Today some 190 entities are generally recognized as sovereign nation-states.

Most of these nations define themselves largely in terms of culture, language, and religion. The United States is somewhat unique in considering itself a nation of immigrants.

Over There: American Doughboys Go to War

In 1917, a High German official scoffed at American might: “America from a military point-of-view means nothing, and again nothing, and for a third time nothing.” The U.S. Army at the time had only 107,641 men.

Within a year, however, the United States raised a five million-man army. By the war’s end, the American armed forces were a decisive factor in blunting a German offensive and ending the bloody stalemate.

Initially, President Wilson hoped to limit America’s contribution to supplies, financial credits, and moral support. But by early 1917, the allied forces were on the brink of collapse. Ten divisions of the French army had begun to mutiny. In March 1917, the Bolsheviks, who had seized power in Russia in November, accepted Germany’s peace terms and withdrew from the war. Then, German and Austrian forces routed the Italian armies.

The United States was forced to quickly assume an active role in the conflict. As a preliminary step, American ships relieved the British of responsibility for patrolling the Western Hemisphere, while another portion of the U.S. fleet steamed to the north Atlantic to combat German submarines.

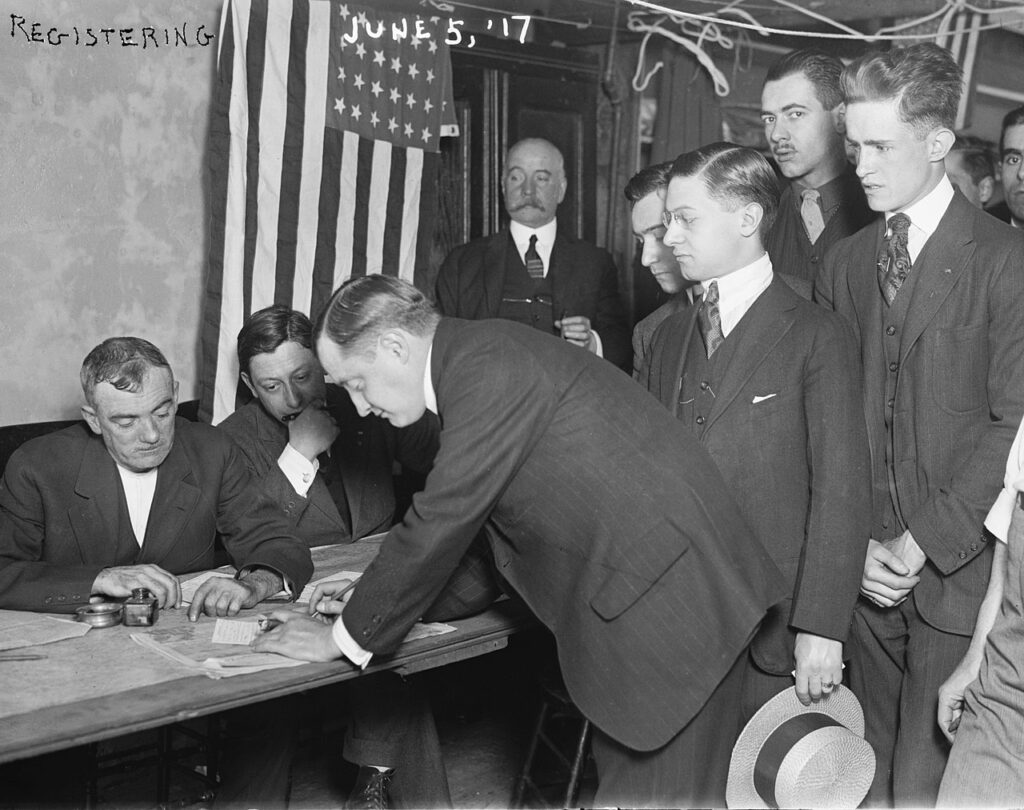

To raise troops, President Wilson insisted on a military draft. More than 23 million men registered during World War I, and 2,810,296 draftees served in the armed forces. To select officers, the army launched an ambitious program of psychological testing.

In March 1918, the Germans launched a massive offensive on the western front in France’s Somme River valley. With German troops barely fifty miles from Paris, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the leader of the French army, assumed command of the allied forces. Foch’s troops, aided by 85,000 American soldiers, launched a furious counteroffensive. By the end of October, the counterattack pushed the German army back to the Belgian border.

American entry into the war quickly overcame the German military’s numerical advantage. In June 1918, some 279,000 American soldiers crossed the Atlantic, in July over 300,000, in August, 286,000 more. All told, 1.5 million American troops arrived in Europe during the last six months of the war. By the end of the conflict, the allies could field 600,000 more men than the Germans. The influx of American forces led the Austro-Hungarian Empire to ask for peace, Turkey and Bulgaria to stop fighting, and Germany to request an armistice.

President Wilson announced that he would negotiate only with a democratic regime in Germany. When the military leaders and the Kaiser wavered, a brief revolution forced the Kaiser to abdicate, and a civilian regime assumed control of the government. At 11:00 a.m., November 11, 1918, the guns stopped.

Historical Debates

Great Debates Should the U.S. Have Entered World War I?

World War I is the most consequential event in the past century and a half. The war to end war resulted in over forty million casualties, including twenty million military and civilian deaths. Among its results were a Second World War, the Holocaust, and the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan.

Far from bringing peace, the Allied victory helped bring about an even more destructive war.

Supporters of Wilson’s decision to declare war on Germany argue that it was a reluctant, measured response to German actions that flagrantly violated international law and threatened U.S. interests. These included:

German War Crimes in Belgium: Following its invasion of Belgium in August 1914, German forces executed about 850 Belgium civilians in four days, accusing them, incorrectly, of being snipers. In subsequent incidents, German troops killed 383 civilians in the Belgian industrial town of Tamines on a single day, 674 in Dinant, and 248 in Louvain. Altogether, massacres of civilians in Belgium left 5,521 dead; another 2,500 civilians died in forced-labor camps.

German Violations of U.S. Rights as a Neutral Nation: The U.S. asserted a right as a neutral nation to trade with all countries, even those at war. This included the right to sell munitions and war materiel. German actions, above all, unrestricted submarine warfare, threated the U.S. right to freedom of the seas. Germany initially took the position that it had a right to sink any vessel carrying war materiel to Allied ports after conducting an inspection of its cargo and after ensuring the safety of the crew.

But in late January 1917, Germany abandoned this policy, and informed the U.S. that it would initiate a campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, attacking merchant ships suspected of carrying arms or other supplies without warning.

In response, President Wilson called for a policy of “armed neutrality.” The government would provide protection and arm American merchant ships against German submarines. But such a policy proved ineffective.

The Zimmermann Note: Around the same time, British intelligence released a German communiqué, in which the Germans offered to reward Mexico with Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico if it joined the German side in the event of war. The Zimmermann Note helped inflamed public opinion and helped sway Congress against Germany.

Others maintain that the U.S. entered the war less for reasons of principle or because of a string of worrisome events than because of underlying cultural ties with Britain and business interests. Although President Wilson called on Americans to be neutral in thought as well as deed, U.S. economic interests aligned closely with the Allies, which were a substantial market for munitions, food stuffs, and loans.

Those who criticize U.S. entry into the war argue that it was unnecessary, since the conflict would have ended in mutual exhaustion in 1917—and thus U.S. entry actually prolonged the conflict. These critics contend that:

- U.S. national security was not threatened, since Germany lacked the power to stage a trans-Atlantic attack.

- U.S. entry into the conflict led to an unprecedented campaign against civil liberties.

- U.S. participation in the war exacerbated ethnic, sectional, and political divisions, and led to heightened animosity toward immigrants.

- The war resulted in a peace settlement that set the stage for future conflicts.

Many historians believe that a fundamental reason that the United States entered the war was because of President Wilson’s desire to shape the peace settlement. Even before U.S. entry, the President called for “peace without victory” and the establishment of a new world order that would guarantee of all nations’ independence, territorial integrity, and freedom from aggression through a league of nations.