Why Vietnam?

John Kennedy and Vietnam

In his 1991 blockbuster, JFK, the director Oliver Stone claimed that President John F. Kennedy was planned to end U.S. involvement in Vietnam in 1965. This claim seems unlikely.

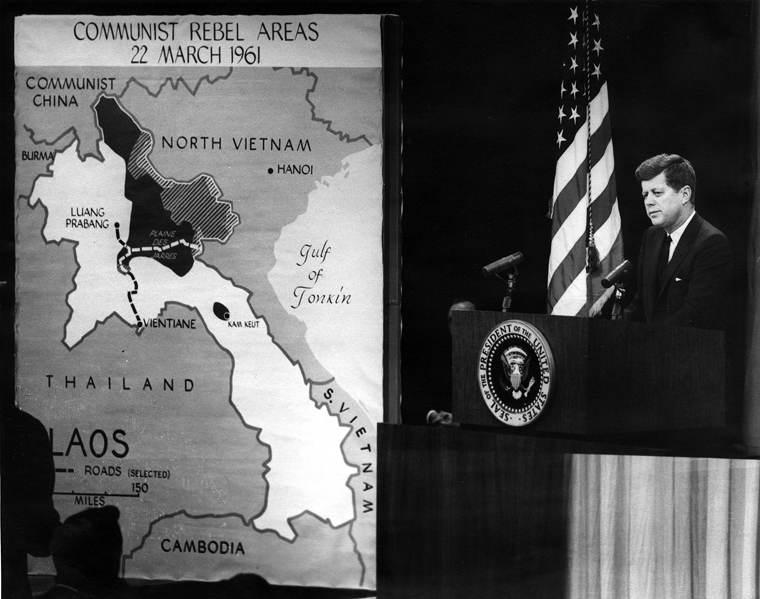

After the erection of the Berlin Wall and the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, an attempt to overthrow the government of Fidel Castro, Kennedy told a New York Times’s reporterJames Reston late in 1961, “Now we have a problem in making our power credible, and Vietnam is the place.” As late as September 26, 1963, two months before his assassination, he stated publicly: “We have to stay with it. We must not be fatigued.”

In fact, President Kennedy escalated US involvement in Vietnam. At the time Kennedy assumed office in 1961, American military involvement in Southeast Asia was limited to arms shipments and no more than 2,000 military advisers. At the time of his death, the number had risen to 16,732. And many of these advisers actually engaged in combat.

In 1961, when Kennedy assumed the presidency, the situation in South Vietnam was worsening. Support for the South Vietnamese government was evaporating. In a country that was predominantly Buddhist, the president was Catholic. The military situation, too, was exceedingly delicate. Arms and supplies from North Vietnam were flowing without interruption into the South, making it virtually impossible to put down the insurgency. Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense, Secretary of State, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff warned that it would be difficult to prevent “the fall of South Vietnam by any measures short of the introduction of U.S. forces on a substantial scale.”

It was during Kennedy’s presidency that the United States made a fateful new commitment to Vietnam. In addition to increasing the number of military advisers, the administration authorized the use of napalm (jellied gasoline), defoliants, and jet planes.

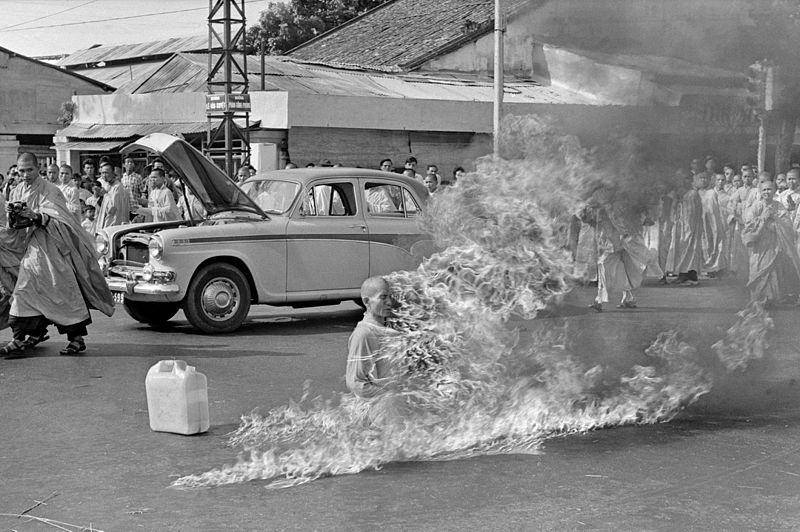

These efforts, however, were not working. By July 1963, Washington faced a major crisis in Vietnam. Buddhist priests had begun to set themselves on fire to protest persecution of Buddhists by South Vietnamese authorities and corruption in the country’s government. The American response was to help engineer the overthrow the South Vietnamese president, Ngo Dinh Diem.

In 1963, South Vietnamese generals overthrew and murdered Diem. It appears that the Kennedy administration sanctioned Diem’s overthrow, partly out of fear that Diem might strike a deal to create a neutralist coalition government including Communists, as had occurred in Laos in 1962. Dean Rusk, Kennedy’s Secretary of State, remarked, “This kind of neutralism…is tantamount to surrender.”

By the spring of 1964, fewer than 150 American soldiers had died in Vietnam. But escalation was already underway. in March 1964, four months after Kennedy’s death, President Lyndon Johnson sent the first 3,500 Marines to Vietnam. Within months he had approved deploying 175,000 combat troops and launched a massive bombing campaign against targets in the North Vietnam.

Podcast

“Why Was the U.S. in Vietnam?”

Listen to the podcast entitled, “Why Was the U.S. in Vietnam?”

Transcript “Why Was the United States in Vietnam”

In his 1972 bestseller, journalist David Halberstam argued that the roots of U.S. involvement in Vietnam came from a series of highly intelligent but extremely arrogant foreign policy experts, intellectuals, and policymakers in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, who knew little about Vietnam itself but had extraordinary faith in American military might and their managerial capabilities and who focused on broad geopolitical concerns rather than realities on the ground.

LBJ

President Lyndon Johnson was reluctant to commit the United States to fight in South Vietnam. “I just don’t think it’s worth fighting for,” he told McGeorge Bundy, his national security adviser. The president, however, feared looking like a weakling if he withdrew from Vietnam, and was convinced that his dream of a Great Society would be destroyed if he backed down on the Communist challenge in Asia. But each step in deepening U.S. involvement in Vietnam made it harder to admit failure and reverse direction.

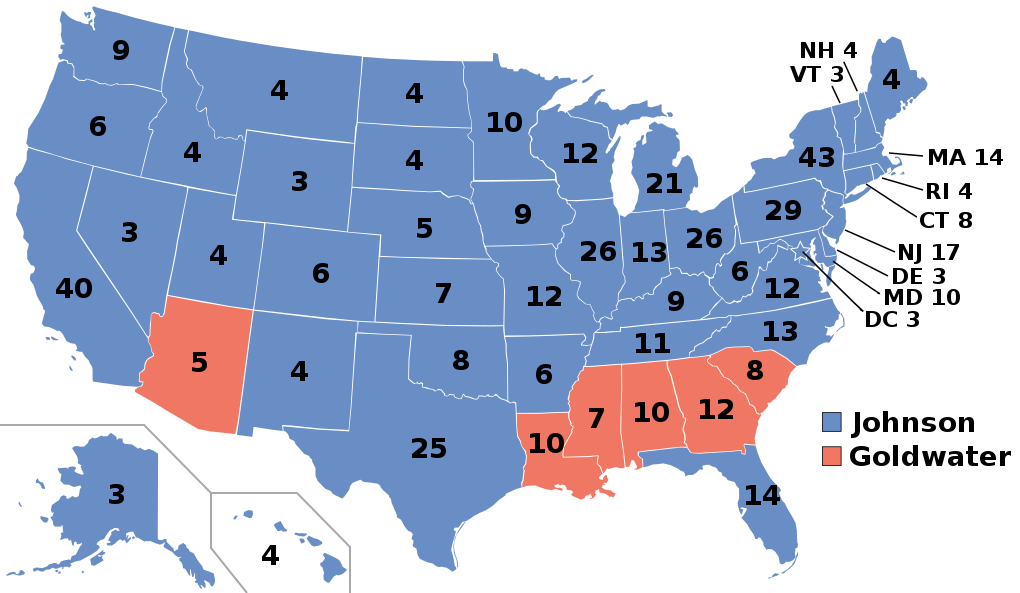

President Johnson campaigned in the 1964 election with the promise not to escalate the war. “We are not about to send American boys 9 or 10,000 miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves,” he said. But following reports that the North Vietnamese had attacked an American destroyer, which was engaged in a clandestine intelligence mission off the Vietnamese coast, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, giving President Lyndon Johnson power to “take all necessary measures.”

In February 1965, Viet Cong units operating autonomously attacked a South Vietnamese garrison near Pleiku, killing eight Americans. Convinced that the Communists were escalating the war, Johnson began the bombing campaign against North Vietnam that would last for 2 ½ years. He also sent the first U.S. ground combat troops to Vietnam.

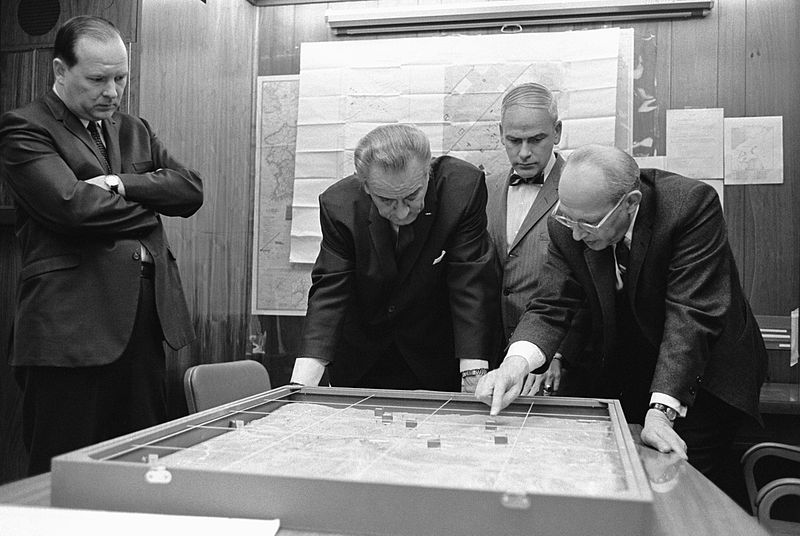

Johnson believed he had five options. One was to blast North Vietnam off the map using bombers. Another was to pack up and go home. A third choice was to stay as we were and gradually lose territory and suffer more casualties. A fourth option was to go on a wartime footing and call up the reserves. The last choice—which Johnson viewed as the middle ground—was to expand the war without going on a wartime footing. Johnson announced that the lessons of history dictated that the United States use its might to resist aggression. “We did not choose to be the guardians at the gate, but there is no one else,” Johnson said. He ordered 210,000 American ground troops to Vietnam.

Johnson justified the use of ground forces by stating that it would be brief, just six months. But the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese were able to match our troop build-up and neutralize the American soldiers. In North Vietnam, 200,000 young men came of draft age each year. It was very easy for our enemy to replenish its manpower. By April 1967, the United States had a force of 470,000 men in Vietnam.

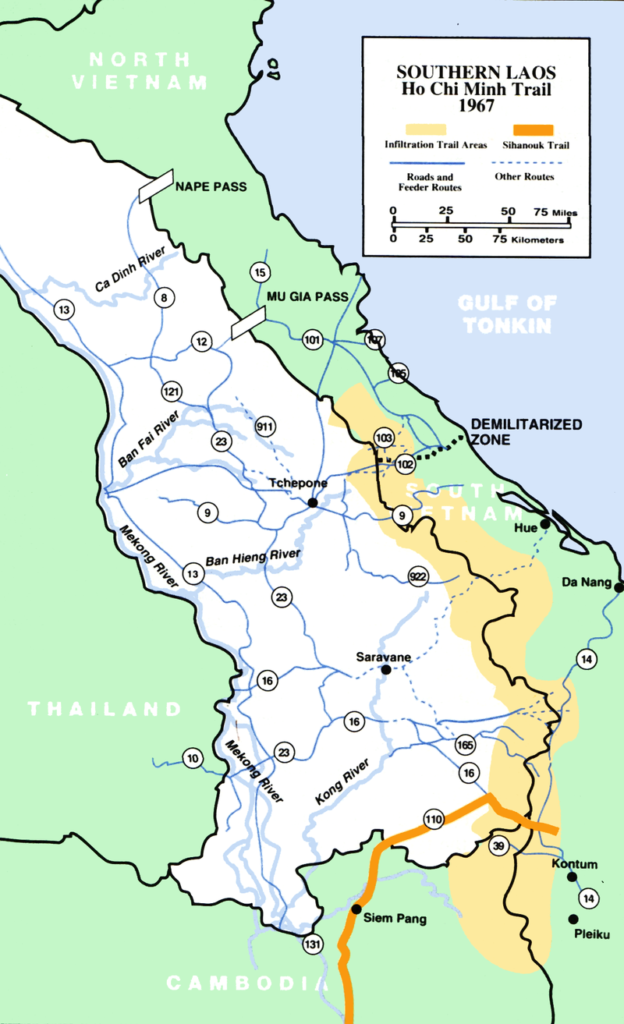

The Johnson administration’s strategy—which included search and destroy missions in the South and calibrated bombings in the North—proved ineffective, though highly destructive. Despite the presence of 549,000 American troops, the United States had failed to cut supply lines from the North along the so-called Ho Chi Minh Trail, which ran along the border through Laos and Cambodia. By 1967, the U.S. goal was less about saving South Vietnam and more about avoiding a humiliating defeat.

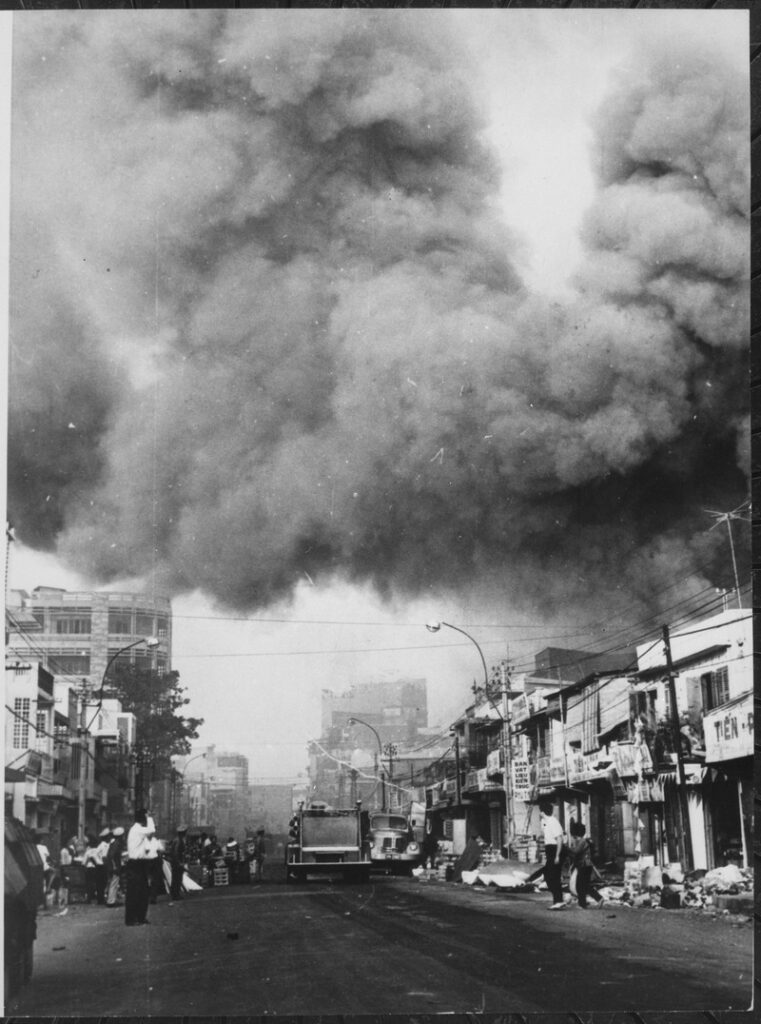

Then, everything fell apart for the United States. U.S. leaders suddenly learned the patience, durability, and resilience of our enemy. In the past, the enemy had fought in distant jungles. But during the Tet Offensive of early 1968, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese fought in cities. across South Vietnam

The size and strength of the 1968 Tet Offensive undercut the optimistic claims by American commanders that their strategy was succeeding. Communist guerrillas and North Vietnamese army regulars blew up a Saigon radio station and attacked the American Embassy, the presidential palace, police stations, and army barracks. Tet, in which more than 100 cities and villages in the South were overrun, convinced many policymakers that the cost of winning the war, if it could be won at all, was out of proportion to U.S. national interests in Vietnam. The former Secretary of State Dean Rusk, who had assured Johnson in 1965 that he was “entirely right” on Vietnam, now stated, “I do not think we can do what we wish to do in Vietnam.” Two months after the Tet Offensive, Johnson halted American bombing in most of North Vietnam and called for negotiations.

As a result of the Tet Offensive, Lyndon Johnson lost much of his support among the American people. He faced a challenge in the 1968 Democratic presidential primary in New Hampshire from Senator Eugene McCarthy, who would pick up more than forty percent of the vote. The next primary was in Wisconsin, and polls showed the president getting no more than thirty percent of the vote. Johnson knew he was beaten and withdrew from the race.

Why Vietnam?

Numerous factors contributed to the U.S. involvement in Vietnam: the Cold War fears of Communist domination of Indochina, a mistaken belief that North Vietnam was a pawn of Moscow, overconfidence in the ability of U.S. troops to prevent the Communist takeover of an ally, and anxiety that withdrawal from Vietnam would result in domestic political criticism. So, too, did a series of events in 1961, including the disastrous attack on Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, the erection of the Berlin Wall, and the threat made by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to sponsor national liberation movements around the world.

The architects of the Vietnam War overestimated the political costs of allowing South Vietnam to fall to Communism. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson feared that losing South Vietnam would damage their chances for re-election, weaken support for domestic social programs, and make Democrats vulnerable to the charge of being soft on Communism. The North Vietnamese strategy was to drag out the war and make it increasingly costly to the United States.

American leaders also grossly underestimated the tenacity of their North Vietnamese and Viet Cong foes. Misunderstanding the commitment of our adversaries, U.S. General William C. Westmoreland said that Asians “don’t think about death the way we do.” In fact, the Vietnamese Communists and Nationalists were willing to sustain extraordinarily high casualties in order to overthrow the South Vietnamese government. The United States intervened in Vietnam without appreciating the fact that the Vietnamese people had a strong nationalistic spirit rooted in centuries of resisting colonial powers. In a predominantly Buddhist country, the French-speaking Catholic leaders of South Vietnam were generally viewed as representatives of France, the former colonial power. Communists were able to capitalize on nationalistic, anti-Western sentiment.

The Tet Offensive

At 3 a.m. on January 31, 1968, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces launched simultaneous attacks on cities, towns, and military bases throughout South Vietnam.

The fighting coincided with the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, Tet. At one point, a handful of Viet Cong wearing South Vietnamese uniforms actually seized parts of the American Embassy in Saigon. The North Vietnamese expected that the Tet attacks would spark a popular uprising.

The Tet offensive had an enormous psychological impact on Americans at home, convincing many Americans that further pursuit of the war was fruitless. A Gallup Poll reported that fifty percent of those surveyed disapproved of President Johnson’s handling of the war, while only 35 percent approved.

When the offensive ended in late February, after the last Communist units were expelled from Vietnam’s ancient imperial city of Hue, an estimated 33,249 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong had been killed, along with 3,470 South Vietnamese and Americans.

Nixon and Vietnam

In the 1968 election, Republican Richard Nixon claimed to have a plan to end the war in Vietnam, but, in fact, it took him five years to disengage the United States from Vietnam. Indeed, Richard Nixon presided over as many years of war in Indochina as did Johnson. About a third of the Americans who died in combat were killed during the Nixon presidency.

Insofar as he did have a plan to bring “peace with honor,” it mainly entailed reducing American casualties by having South Vietnamese soldiers bear more of the ground fighting—a process he called “Vietnamization”—and defusing anti-war protests by ending the military draft. Nixon provided the South Vietnamese army with new training and improved weapons and tried to frighten the North Vietnamese to the peace table by demonstrating his willingness to bomb urban areas and mine harbors. He also hoped to orchestrate Soviet and Chinese pressure on North Vietnam.

The most controversial aspect of his strategy was an effort to cut the Ho Chi Minh supply trail by secretly bombing North Vietnamese sanctuaries in Cambodia and invading that country and Laos. The U.S. and South Vietnamese incursion into Cambodia in April 1970 helped destabilize the country, provoking a bloody civil war and bringing to power the murderous Khmer Rouge, a Communist group that evacuated Cambodia’s cities and threw thousands into re-education camps.

Following his election, President Nixon began to withdraw American troops from Vietnam in June 1969 and replaced the military draft with a lottery in December of that year. In December 1972, the United States began large-scale bombing of North Vietnam after peace talks reach an impasse. The so-called Christmas bombings led Congressional Democrats to call for an end of U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia.

In late January 1973, the United States, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong, and North Vietnam signed a cease-fire agreement, under which the United States agreed to withdraw from South Vietnam without any comparable commitment from North Vietnam. Historians still do not agree whether President Nixon believed that the accords gave South Vietnam a real chance to survive as an independent nation, or whether he viewed the agreement as a face-saving device that gave the United States a way to withdraw from the war “with honor.”

The War at Home

The United States won every battle it fought against the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong, inflicting terrible casualties on them. Yet, it ultimately lost the war because the public no longer believed that the conflict was worth the costs.

The first large-scale demonstration against the war in Vietnam took place in 1965. Small by later standards, 25,000 people marched in Washington. By 1968, strikes, sit-ins, rallies, and occupations of college buildings had become commonplace on elite campuses, such as Berkeley, Columbia, Harvard, and Wisconsin.

The Tet Offensive cut public approval of President Johnson’s handling of the war from 40 to 26 percent. In March 1968, anti-war Democrat Eugene McCarthy came within 230 votes of defeating Johnson in the New Hampshire primary. Anti-war demonstrations grew bigger. At the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago, police beat anti-war protesters in the streets while the Democrats nominated Hubert Humphrey for president. Ironically, the anti-war protesters probably helped to elect Richard Nixon as president in 1968 over Humphrey and in 1972 over George McGovern. Anti-war demonstrations peaked when 250,000 protesters marched in Washington, D.C., in November 1969.

President Nixon’s decision to send American troops into Cambodia triggered a new wave of campus protests across the nation. When National Guardsmen at Kent State University shot four students to death in northeastern Ohio, 115 colleges went on strike, and California Governor Ronald Reagan shut down the state’s university system.

The Final Collapse

On the morning of April 30, 1975, a column of seven North Vietnamese tanks rolled down Saigon’s deserted streets and crashed through the gates of South Vietnam’s presidential palace. A soldier leapt from the lead tank and raised a red, blue, and yellow flag. The Vietnam War was over.

Tens of thousands of South Vietnamese massed at the dock of Saigon harbor, crowding into fishing boats.

In the fall of 1974, President Nguyen Van Thieu of South Vietnam abruptly ordered his commanders to pull out of the central highlands and northern coast. His intention was to consolidate his forces in a more defensible territory. However, the order was given so hastily, with so little preparation or planning, that the retreat turned into an uncontrollable panic. Consequently, North Vietnamese forces were able to advance against little resistance. On April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese soldiers captured Saigon, bringing the Vietnam War to an end.