Into the Quagmire

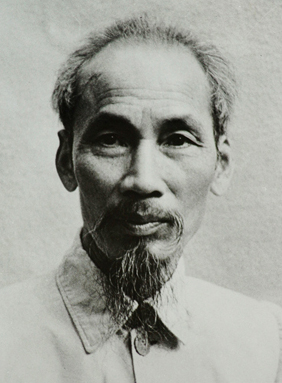

Ho Chi Minh

Ho Chi Minh was a tiny man, frail in appearance and extremely deferential. He wore simple shorts and sandals. To his followers, he was known simply as “Uncle Ho.”

Ho Chi Minh was born in 1890 in a village in central Vietnam. In 1912, he left his homeland and signed aboard a French freighter. For a time, he lived in the United States—visiting Boston, New York, and San Francisco. Ho was struck by Americans’ impatience. Later, during the Vietnam War, he told his military advisers, “Don’t worry, Americans are an impatient people. When things begin to go wrong, they’ll leave.”

After three years of travel, Ho Chi Minh settled in London where he worked at the elegant Carlton Hotel. He lived in squalid quarters and learned that poverty existed even in the wealthiest, most powerful countries. In Paris, he came into contact with the French left. He was still in Paris when World War I ended and the peace conference was held. Inspired by Woodrow Wilson’s call for universal self-determination, Ho wrote,” all subject peoples are filled with hope by the prospect that an era of right and justice is opening to them.”

Ho wanted to meet Wilson and plead the cause of Vietnamese independence. Wilson ignored his request.

Ho then traveled to Moscow, where Lenin had declared war against imperialism. While in the Soviet Union, Ho embraced socialism. By the early 1920s, he was actively organizing Vietnamese exiles into a revolutionary force.

In 1941, Ho returned to Vietnam. The time was right, he believed, to free Vietnam from colonial domination. Ho aligned himself with the United States. In 1945, borrowing passages from the Declaration of Independence, Ho declared Vietnamese independence.

However, the French, who returned to Vietnam after World War II, had different plans for Vietnam.

Into the Quagmire

The failure of South Vietnam to fulfill the terms of the Geneva Accord and allow unification elections to take place led the North Vietnamese to distrust diplomacy as a way to achieve a settlement.

In 1955, the first U.S. military advisers arrived in Vietnam. President Dwight D. Eisenhower justified this decision on the basis of the domino theory—that the loss of a strategic ally in Southeast Asia would result in the loss of others. “You have a row of dominoes set up,” he said, “you knock the first one, and others will fall.” President Eisenhower felt that with U.S. help, South Vietnam could maintain its independence.

In 1957, South Vietnamese rebels known as the Viet Cong began attacks on the South Vietnamese government of Ngo Dinh Diem. In 1959, North Vietnam approved armed struggle against Ngo Dinh Diem’s regime in Saigon.

The Causes of War

War is as old as human history, but that does not mean that violent conflict is “rooted in biology” or “hard-wired” in human nature. Rather, wars are the product of ideology and social circumstances. In the past, wars were often fought over God, glory, and gold: on behalf of a religious faith or to acquire power, territory, slaves, and wealth.

Such motives still exist. But over the past two hundred years, many wars have been fought for other reasons: out of a sense of nationalism, out of ethnic antagonism, out of manipulation by demagogues, in response to economic decline—not to mention miscalculation, fear, power hunger, or disruptions in the international balance of power.

The rise of the modern nation state was a major contributor to war, and not simply because industrialization produced weapons more deadly than ever came before. Nation states tend to possess a monopoly on legitimate, organized force, which has had the effect, over time, of reducing certain kinds of violence, including mob violence, lynchings, and riots. But when wars or internal conflicts erupt, the death tolls can be staggering.

A strong sense of national identity accompanied the development of the nation state. Especially in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was a sense that nations were engaged in a Darwinian struggle for survival, which encouraged the violence that accompanied national expansion, the violent quest for colonies, and ultimately direct conflict between the major imperial powers.

In addition, the rise of the nation state spurred the growth of ethnic consciousness. Whereas empires had included a wide range of ethnicities and nationalities, the modern nation state often sought to purge “alien” elements. And European colonialism often resulted in the “invention” of new ethnic groups that often struggled over resources or political influence.

Meanwhile, the patriotism that accompanied the growth of the nation state encouraged many young men to put their lives on the line on behalf of their homeland.

Ideology, too, proved to be a powerful contributor to war, from Napoleonic France’s efforts to spread “Enlightenment” values across Europe to the titanic twentieth century struggles between fascism, Communism, and liberal democracy. During the twentieth century, conflicts involving fascism and Communism produced well over 100 million deaths.

Not surprisingly, economic decline and uncertainty have often contributed to the outbreak of war. The most notable example involves Germany in the 1930s.

In recent years, self-interested outsiders have played a crucial role in fomenting and prolonging wars. In Syria, for example, Russia, the United States, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, and Qatar, helped intensify and prolong the conflict through their arms, training, and direct military intervention.

Among the bloodiest wars in recent years was the Second Congo War, which began in 1998 and resulted in about five million deaths. Of the nine African nations involved, eight had, at one point or another, been provided with arms and military training by the U.S. government.

The collapse of authoritarian or highly centralized regimes, too, contributed to violent conflict within and between states. The breakup of the Soviet Union, for example, contributed to conflicts between Georgia and Armenia and between Ukraine and Russia.

Ironically, the policies of international organizations—which are often thought to contribute to international peace and prevent war—have also spurred conflict by imposing severe austerity policies upon countries. Neo-liberal policies that required countries to eliminate subsidies for agriculture, liberalize trade, devalue the local currency, privatize state enterprises, and reduce the number of civil servants contributed to the outbreak of violence in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia by sharply reducing employment, especially among the young, and by generating struggles for control of the government.

The modern nation state has also contributed to violence in yet another way. It gave government insiders and outsiders access to media that allows them to disseminate propaganda, stigmatize adversaries, and arouse tensions. In Iraq, for example, extremists terrorized minority groups, leading them to flee, and resulted in the seizure of their property. In Rwanda, Tutu propagandists spurred the killing of 800,000 Tutsis in the course of 100 days. In both instances, groups that had lived together peacefully for decades and frequently intermarried turned against one another, as certain groups sought to scapegoat other ethnic groups and use social conflict for their own purposes.