The Meaning of the Vietnam War

History Through…

…Photographs

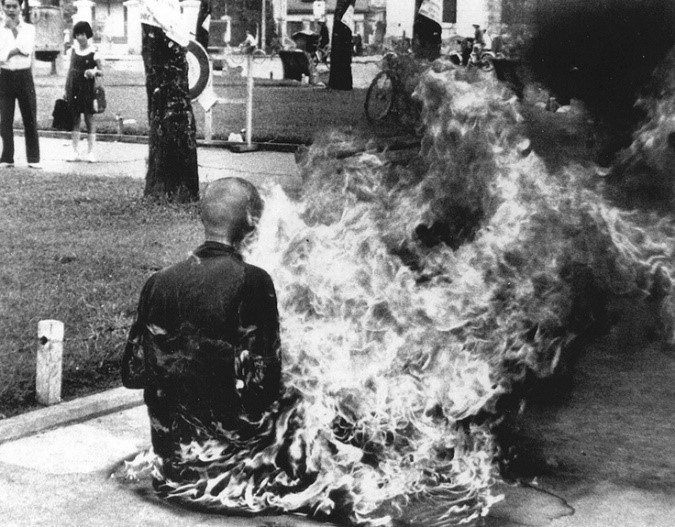

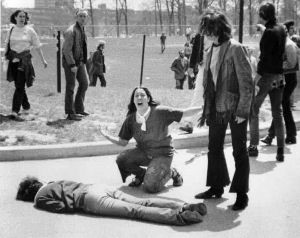

The prize-winning photographs are among the most searing and painful images of the Vietnam War era. These images helped define the meaning of the war. They also illustrate the immense power of photography to reveal war’s brutality.

One photograph shows a Buddhist monk calmly burning himself to death to protest the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese government. Photographs of this horrific event raised a public outcry against the corruption and religious discrimination of the government of Ngo Dinh Diem, the Catholic president of South Vietnam. Eight more monks and nuns immolated themselves in the following months.

Another photograph shows a nine-year-old girl, running naked and screaming in pain after a fiery napalm attack on her village. The napalm (jellied gasoline) has burned through her skin and muscle down to her bone. The photograph of her anguished, contorted face helped to end American involvement in the Vietnam War.

A third image shows a stiff-armed South Vietnamese police chief about to shoot a bound Viet Cong prisoner in the head. The victim, a Viet Cong lieutenant, was alleged to have wounded a police officer during North Vietnam’s Tet offensive of 1968. The photograph became a symbol of the war’s casual brutality.

A fourth photograph, taken by a twenty-one-year-old college journalist, shows the body of a twenty-year-old student protestor at Ohio’s Kent State University lying limp on the ground, shot to death by National Guardsmen. In the center of the picture, a young woman kneels over the fallen student, screaming and throwing up her arms in agony.

A fifth picture captured the fall of Saigon during the last chaotic days of the Vietnam War. The photo shows desperate Vietnamese crowding on the roof of the U.S. Agency for International Development building trying to board a silver Huey helicopter. Taken on April 30, 1975, the photograph captured the moment when the last U.S. officials abandoned South Vietnam, and South Vietnamese military and political leaders fled their own country, while hundreds of Vietnamese left behind raise their arms helplessly.

Photographs have the power to capture an event and burn it into our collective memory. Photographs can trap history in amber, preserving a fleeting moment for future generations to re-experience. Photographs can evoke powerful emotions and shape the way the public understands the world and interprets events. Each of these pictures played a role in turning American public opinion against the Vietnam War. But pictures never tell the full story. By focusing on a single image, they omit the larger context essential for true understanding.

Phan Thi Kim Phuc, the nine-year-old girl running naked down the road in the photograph, was born in 1963 in a small village in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. She was the daughter of a rice farmer and a cook. In June 1972, she and her family took refuge in a Buddhist temple when South Vietnamese bombers flew over her village. Four bombs fell toward her. The strike was a case of friendly fire, the result of a mistake by the South Vietnamese air force.

There was an orange fireball, and she was hit by napalm. Her clothes were vaporized. Her ponytail was sheared off by the napalm. Her arms, shoulders, and back were so badly burned that she needed 17 major operations. She started screaming, “Nong qua! Nong qua!” (too hot!) as she ran down the road. Her scarring is so severe that she will not wear short-sleeve shirts to this day. She still suffers from severe pain from the burns, which left her without sweat or oil glands over half of her body.

Two infant cousins died in the attack, but she, her parents, and seven siblings survived. The man who took her photograph, 21-year-old Huynh Cong “Nick” Ut, was also Vietnamese. His brother was killed while covering combat in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta for the Associate Press. After the napalm attack, Ut put her into a van and rushed her to a South Vietnamese hospital, where she spent fourteen months recovering from her burns.

In 1986, Kim Phuc (whose name means “Golden Happiness”) persuaded the Vietnamese government to allow her to go to Cuba to study pharmacology. In 1992, while in Cuba, she met and married a fellow Vietnamese student. Later that year, she and her husband defected to Canada while on a flight from Cuba to Moscow. Today, she serves as an unpaid Goodwill Ambassador for UNESCO and runs a non-profit organization that provides aid to child war victims. Her husband cares for mentally disabled adults.

General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, the South Vietnamese police chief who executed the Viet Cong prisoner in 1968, had a reputation for ruthlessness. While serving as a colonel in 1966, he led tanks and armored vehicles into the South Vietnamese city of Danang to suppress rebel insurgents. Hundreds of civilians as well as Viet Cong were killed. In early 1968, at the height of the Tet offensive, Loan was working around the clock to defend the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon. He had asked a regimental commander to execute the prisoner, but when the commander hesitated, Loan said, “‘I must do it.’ If you hesitate, if you didn’t do your duty, the men won’t follow you.”

The photograph taken at Kent State in Ohio shows a terrified young woman, Mary Ann Vecchio, a fourteen-year-old runaway from Florida, kneeling over the body of Jeffrey Miller. Miller, a Kent State University student, had been protesting American involvement in Vietnam even before attending college. At the age of fifteen, he had composed a poem titled “Where Does It End,” expressing his horror about “the war without a purpose.”

Miller was shot and killed during an anti-war protest that followed the announcement that U.S. troops had moved into Cambodia. An ROTC building on the university’s campus was burned, and in response, the mayor of Kent called in the National Guard.

On May 4, 1970, the guardsmen threw tear gas canisters at the crowd of student protesters. Students threw the canisters back along with rocks, the guardsman later claimed. The 28 guardsmen fired more than 60 shots, killing four students (two of them protesters) and injuring nine (one was left permanently paralyzed).

A Justice Department report determined that the shootings were “unnecessary, unwarranted and inexcusable,” but an Ohio grand jury found that the Guard had acted in self-defense and indicted students and faculty for triggering the disturbance.

The Vietnam War was the first and perhaps the last “living room war,” with its reality brought directly into American homes through graphic, largely uncensored imagery on television and in magazines and newspapers.

The Meaning of the Vietnam War

For today’s students, the Vietnam War is an event that occurred more than a quarter century before their birth. Now that the United States and Vietnam have normalized relations, it is especially difficult for many young people to understand why the war continues to evoke deeply felt emotions. Thus, it is especially important for students to learn about a war whose consequences strongly influence attitudes and policies even today.

The Vietnam War was the first war to come into American living rooms nightly, and the only conflict that ended in defeat for American arms. The war caused turmoil on the home front, as anti-war protests became a feature of American life. Americans divided into two camps—pro-war hawks and anti-war doves.

The questions raised by the Vietnam War have not faded with time. Even today, Americans still ask:

- Whether the American effort in Vietnam was a sin, a blunder, or a necessary war; or whether it was a noble cause, or an idealistic, if failed, effort to protect the South Vietnamese from totalitarian government.

- Whether the military was derelict in its duty when it promised to win the war, or whether arrogant civilians ordered the military into battle with one hand tied and no clear goals.

- Whether the American experience in Vietnam should stand as a warning against state building projects in violent settings; or whether it taught Americans to perform peacemaking operations and carry out state building correctly.

- Whether the United States’ involvement in Vietnam meant it was obligated to continue to protect its South Vietnamese allies once the war was over.