Overview: Vietnam War

Overview

The Vietnam War was the longest, costliest, and most divisive American war of the twentieth century. For a quarter century, the United States sought unsuccessfully to prevent South Vietnam from becoming a Communist country, first by supporting France’s efforts to defeat Communist nationalists, and then, by using American aid and military force to support pro-American governments in South Vietnam. The conflict cost 58,000 American lives and one to two million Vietnamese combatants and civilians. In addition, the war displaced some 10 million South Vietnamese.

American involvement in Vietnam was a product of a Cold War mentality. Despite warnings that the United States would find itself in a “bottomless military and political swamp” (as France’s President Charles de Gaulle told John F. Kennedy), five presidents — Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon — maintained U.S. involvement in Vietnam at a high price in terms not simply of lives and money, but in many other ways: In the emergence of deep political divisions at home and harm to the nation’s reputation overseas.

More than four decades after the war ended, the conflict continues to arouse controversy. Debates still rages about what motivated the United States to intervene in Vietnam: To resist Communist aggression? To prevent the loss of much of Southeast Asia to Communism? Or were some other factors driving American policy, such as a desire to maintain U.S. credibility or to halt movements of national liberation?

Moral debates also rage. Was the Vietnam War a noble cause, a tragic mistake, a misguided aberration, or an immoral intervention into what was a civil war?

Then, too, there is the practical question: Could the United States have preserved a non-Communist South Vietnam by adopting a different strategy?

The Road to the Vietnam War

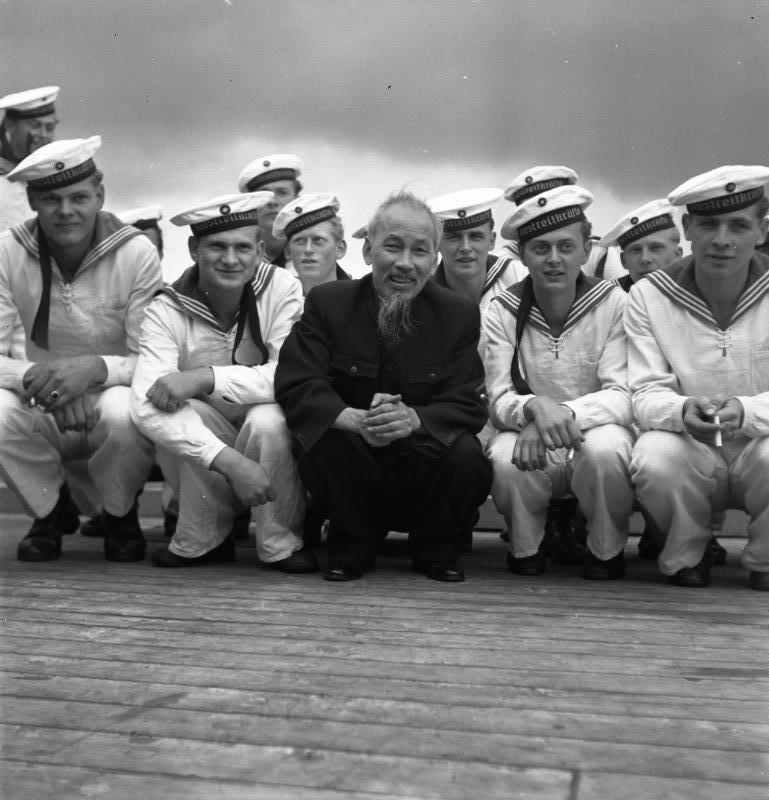

U.S. involvement in Vietnam began shortly after the end of World War II. Vietnam had been under French colonial rule since the mid-nineteenth century, and a source of of tea, rice, coffee, pepper, coal, zinc and tin. But during the Second World War, Japanese forces invaded Vietnam, and dislodged the French. Leading resistance to the Japanese was Ho Chi Minh, a Vietnamese nationalist sympathetic to Communism. When the war was over, France sought to reimpose colonial rule.– only to be challenged by Ho and his supporters, who announced establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the country’s north. Armed conflict between Ho’s Viet Minh forces and French-backed forces in the south raged from 1946 to 1954.

After World War II, neither France nor England wanted to see the end of their colonial empires. England was anxious to control Burma, Malaya, and India. France wanted to rule Indochina.

Under Franklin Roosevelt, the United States sought to bring an end to European colonialism. As he put it, condescendingly: “There are 1.1 billion brown people. In many Eastern countries they are ruled by a handful of whites and they resent it. Our goal must be to help them achieve independence. 1.1 billion potential enemies are dangerous.”

But under Harry Truman, the United States was concerned about its naval and air bases in Asia. The U.S. decided to permit France into Indochina to re-assert its authority in Southeast Asia. The result: The French Indochina War began.

From the beginning, American intelligence officers knew that France would find it difficult to re-assert its authority in Indochina. The French, however, refused to listen to American intelligence. To them, the idea of Asian rebels standing up to a powerful Western nation was preposterous.

Although President Truman allowed the French to return to Indochina, he was not yet prepared to give the French arms, transportation, and economic assistance. It was not until anti-Communism became a major issue that the United States would take an active role supporting the French. The fall of China, the outbreak of the Korean War, and the rise of Joe McCarthy would lead policymakers to see the French War in Vietnam, not as a colonial war, but as a war against international Communism.

Beginning in 1950, the United States started to underwrite the French war effort. For four years, the United States provided $2.6 billion; however, this had little effect on the war. The French command, frustrated by a hit-and-run guerrilla war, devised a trap. The idea was to use a French garrison as bait, have the enemy surround it, and mass their forces. Then, the French would strike and crush the enemy and gain a major political and psychological victory.

The French built their positions at Dien Bien Phu in northwestern Vietnam. The French located a network of eight bases, surrounded by barbed wire and minefields, in a valley and left the high ground to their adversaries. An American asked what would happen if the enemy had artillery. A French officer assured him that they had no artillery, and even if they did, they would not know how to use it. Yet, as the journalist David Halberstam noted, “They did have artillery and they did know how to use it.”

The Viet Minh, Vietnamese Nationalists led by Ho Chi Minh, bombarded these bases with artillery from the surrounding hillsides. Heavy rains made it impossible to bomb the Vietnamese installations or to supply the garrisons. The French, trapped, were reduced to eating rats and pleading for American air support.

Despite support from Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, President Eisenhower was not willing to commit American air support without support from Britain, Congress, and the chiefs of staff. Following the advice of Winston Churchill, General Matthew Ridgway, and Senator Lyndon Johnson, President Eisenhower decided to stay out.

On May 7, 1954, a ragtag army of 50,000 Vietnamese Communists decisively defeated the remnants of an elite French force at Dien Bien Phu.

Despite American financial supports, amounting to about three-quarters of France’s war costs, 250,000 veteran French troops were unable to crush the Viet Minh. Altogether, France had 100,000 men dead, wounded, or missing trying to re-establish its colonial empire.

The French defeat was followed by a peace conference in Geneva, Switzerland. Under the Geneva Accords, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam received their independence, and Vietnam was to be temporarily divided between an anti-Communist South and a Communist North pending elections to be held in 1956 to reunify the country. However, South Vietnam, with U.S. backing, refused to hold unification elections, convinced that Ho Chi Minh would win an overwhelming victory at the polls.

Consequences

- The Vietnam War cost the United States 58,000 lives and 350,000 casualties. It also resulted in between one and two million Vietnamese deaths.

- Congress enacted the War Powers Act in 1973, requiring the president to receive explicit Congressional approval before committing American forces overseas.