The Rise of Modern America

Chicago and the Rise of the Modern America

In each decade, a single city has often served as a symbol of broader social transformations. There was Los Angeles in the 1940s, San Francisco in the 1960s, Houston in the 1970s, and Miami in the 1980s. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Chicago was the place that foreigners went to see what America was really about. The poet Carl Sandburg called it the “City of the Big Shoulders.” The author Theodore Dreiser dubbed it “a new world” in the making. The British writer Rudyard Kipling declared that “the other places do not count. This place is the first American city I have encountered…Having seen it, I urgently desire never to see it again.”

Chicago was not only the center of railroads, meat packing, and grain—it also was the center of a literary renaissance. Many of the nation’s foremost writers gravitated to Chicago, like Hamlin Garland, Upton Sinclair, and Sinclair Lewis.

In less than a century, an empty piece of prairie located where the Great Lakes and Great Plains converged was transformed into an urban behemoth of towering skyscrapers, sprawling stockyards and immense factories. As the terminus for four percent of the world’s railroads, Chicago also became the center of the nation’s mail order business, serving as headquarters both for Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward.

It was in Chicago that modern architecture and urban design were born. Following the Great Fire of 1871, Chicago rebuilt itself into a modern city, complete with imposing municipal parks, wide boulevards, imposing public buildings, and something entirely new: the skyscraper. Chicago was at the very center of competing schools of design, from neoclassicism to the modernist architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Chicago was also a city of almost unbelievable filth and squalor, of desperate poverty and exploitation, of wrenching labor conflict and radicalism. Chicago was the setting for the symbols of labor-related violence, including the 1886 Haymarket Square bombing, the 1893 assassination of the city’s mayor, and the nation’s most visible labor strike, the 1894 Pullman strike.

However, it was also in Chicago that a new popular culture was taking shape. The nineteen-year-old magician and escape artist Harry Houdini was there, as was the strong man Bernarr Macfadden and the impresario Florence Zeigfeld.

Chicago was also central to the emergence of new kinds of American music. In Chicago, ragtime gained popularity, altering the beat, rhythm, and pace of popular music. Chicago would soon become a center for other kinds of music heavily influenced by African Americans, including the blues and jazz.

Today, only one of the 1893 fair’s buildings survives: the Fine Arts Building, recast as the Museum of Science and Industry.

The Cotton States and International Exposition, 1895

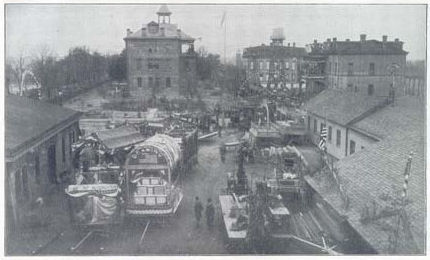

Two years after the World’s Columbian Exposition closed, another fair opened in Atlanta. It was just thirty-one years since the city had been burned to the ground by General William Tecumseh Sherman. The Atlanta exposition contained a horse track for racing, handsome Greek-columned buildings, beautiful lawns and lakes and express trains to downtown. The city’s leaders wanted to lure Northern wealth, create jobs and present Atlanta as a sophisticated place.

In one year of hectic construction, 500 workers carved a park and two lakes out of the clay hills. Using plaster of Paris, lumber and shingles, they built fifty fancy, though temporary, structures. And 800,000 visitors came to marvel at it all.

Compared with the 1893 Chicago Exposition, Atlanta’s fair was strictly minor league. It cost one-ninth as much, the midway was one-fourth as long and the Ferris wheel was half as big as Chicago’s.

In their efforts to attract business to Atlanta, leaders tried to dispel worries about racial problems. Construction of a Negro Pavilion was mandated by Congress as a condition for $200,000 in federal appropriations. The building, intended to feature “the progress made by the Negro since emancipation.”

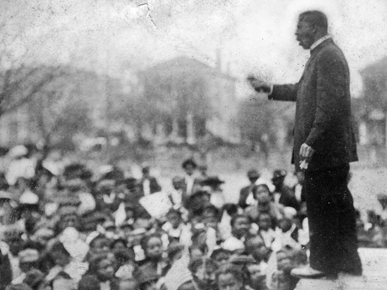

The Cotton States Exposition put Atlanta on the map. The fair linked Atlanta with the New South in the national mind. It also marked the ascent of a new African American leader, a former slave, Booker T. Washington. Frederick Douglass, the old, great African-American leader who had seen his people through slavery, had died several months earlier. Washington closed the vacuum in leadership almost immediately.

Booker T. Washington no longer enjoys the esteem he once did—when almost every city in the segregated South had a ”colored” school named in his honor.

Indeed, there was a time when his gospel of patience, thrift, hard work, and education was viewed as the sole means of what an earlier generation called ”Negro uplift.”

Today, Washington’s political philosophy of patience, thrift, hard work, racial accommodation, and gradualism, when faced with the white racism of his time, seems thoroughly discredited. His idea that the education of blacks should focus primarily on, what today we would call, ”vocational training” seems like a tacit acceptance of what most whites in his time believed: that blacks should accept only the most rudimentary education.

Washington delivered a speech at the opening of the Fair that thrust him to national prominence. Within a short time, this son of a black slave woman and a white father was anointed by the white press of his day as the spokesman and the ”representative of the Negro race in America.” It was a mantle he would wear until his death in 1915.

In an oft quoted line from his speech, Washington declared: “In all things that are purely social we (blacks and whites) can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

He continued: ”The wisest of my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly…. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared to exercise those privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is infinitely more important than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera house.”

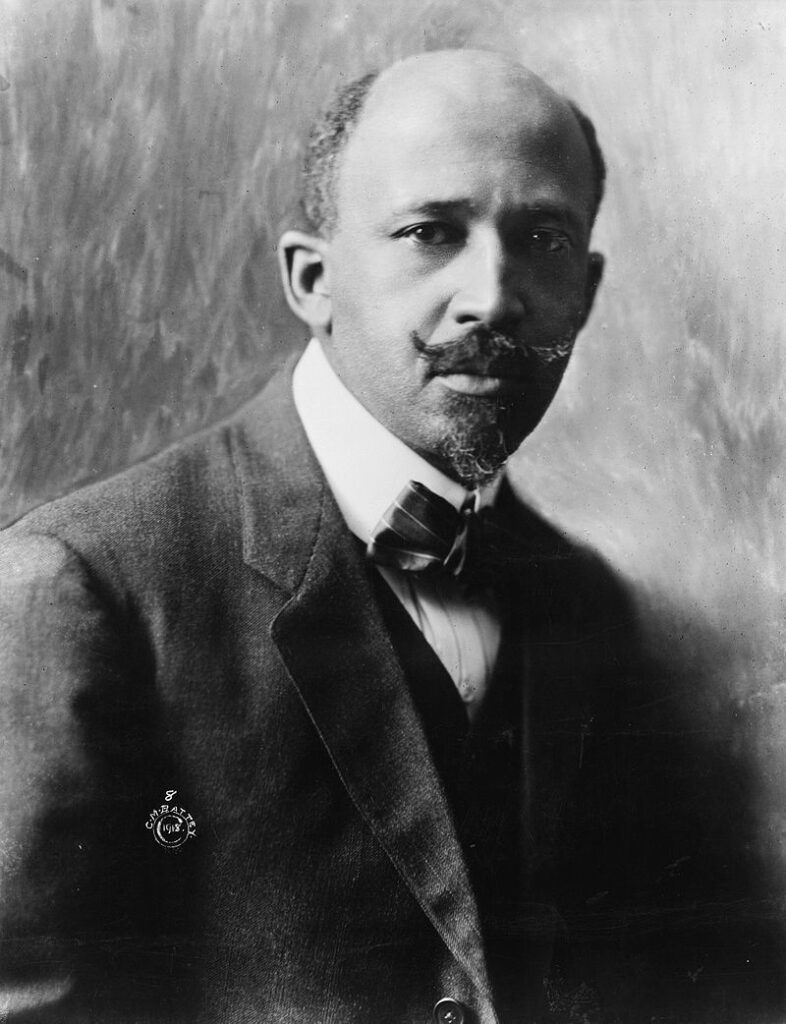

Many African American leaders, led by W.E.B. DuBois, Harvard’s first black Ph.D. and a founder of the NAACP, soon condemned the speech as the wrong approach to take at a time when blacks were losing the few rights they had won since the Civil War. Southern states were stripping away the right of blacks to vote. Lynchings were on the increase. A year after Washington’s speech, the U.S. Supreme Court sanctioned segregation in the public schools. And in the popular culture of the time, blacks were the steady object of ridicule and scorn in books, magazines and newspapers.

Booker T. Washington, “Atlanta Compromise”

First listen to Booker T. Washington’s “Atlanta Compromise” speech

“Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Board of Directors and Citizens: One-third of the population of the South is of the Negro race. No enterprise seeking the material, civil, or moral welfare of this section can disregard this element of our population and reach the highest success.

… To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man, who is their next-door neighbor, I would say: “Cast down your bucket where you are”— cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded.

Cast it down in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service, and in the professions. … Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour…. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities.

To those of the white race who look to the incoming of those of foreign birth and strange tongue and habits for the prosperity of the South, were I permitted I would repeat what I say to my own race, “Cast down your bucket where you are.” Cast it down among the eight millions of Negroes whose habits you know, whose fidelity and love you have tested in days when to have proved treacherous meant the ruin of your firesides. Cast down your bucket among these people who have, without strikes and labour wars, tilled your fields, cleared your forests, builded your railroads and cities, and brought forth treasures from the bowels of the earth, and helped make possible this magnificent representation of the progress of the South.

… The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly…” -Booker T. Washington