Expositions and Fairs as History

World’s Fairs as History

It is curious that in our current age of globalization, world’s fairs have largely disappeared.

Since World War II, there have only been four official world’s fairs: in Brussels, Belgium, in 1958, Montreal, Canada, in 1967, Osaka, Japan, in 1970, and Seville, Spain, in 1992.

Although there would be influential world’s fairs in the twentieth century—such as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904 and the 1939 New York World’s Fair, which focused on “the world of tomorrow”—the second half of the nineteenth century was the golden age of world’s fairs. The prototype for later fairs was the Crystal Palace Exposition in London in 1851, which drew more than six million visitors who came to celebrate the industrial revolution and view some 13,000 exhibits. The symbol of the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle was the Eiffel Tower.

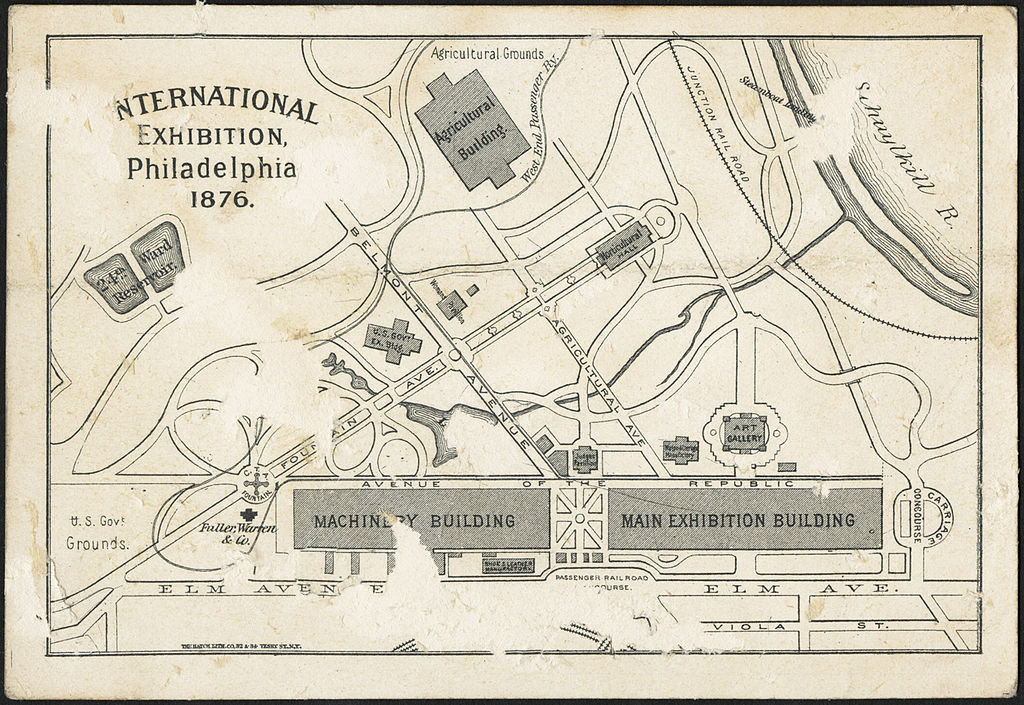

Three late-nineteenth century American expositions were of particular significance. The Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 commemorated a century of American independence. The World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 marked the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of the New World. The Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895 sought to attract northern investment into the New South three decades after the end of the Civil War.

The Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia, 1876

To celebrate the one-hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the United States held its first international exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. After ten years of planning, the exposition ran for over five months. Nearly ten million people attended.

The exposition covered over 450 acres, and more than thirty thousand exhibitors from the thirty-eight states and fifty nations participated. The exhibits were placed in seven categories, most of which reflected the predominantly industrial orientation of the exhibition: mining and metallurgy, manufactured products, science and education, machinery, agriculture, fine arts, and horticulture.

The exposition’s central symbol was the gigantic Corliss Steam Engine, demonstrating that industrial America had come of age. The exposition was also an effort to proclaim American greatness and affirm national unity to Americans weary of Reconstruction and the political scandals of the Grant administration.

The World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s epoch voyage of discovery, Chicago built an entire new city—”The White City”—larger, more elaborate, and more truly international in scope than any previous fair.

The White City represented an unprecedented collaboration of artists, architects, engineers, sculptors, painters, and landscape architects who joined forces to create a single work—an ideal model city. Lauded as an American Venice, the White City consisted of a “Court of Honor” of classically styled white buildings with columns and gilded domes linked to the other parts of the grounds by a series of lagoons and canals. Leading national architects and architectural firms including Richard Morris Hunt, McKim, Mead, and White, and Louis Sullivan designed the major buildings. Well-known sculptors, such as Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French designed the architectural decorations.

“The Pledge of Allegiance” was written so that school children could participate in the fair’s dedication.

There were 65,000 exhibits displayed at the fair, showcasing every conceivable product from a 1,500-pound chocolate Venus de Milo to a 46-foot cannon by Krupp, the German munitions manufacturer. Among the many products introduced at the fair were Cracker Jacks, Aunt Jemima Syrup, Cream of Wheat, Pabst Beer, and Juicy Fruit gum. The Fair also introduced picture postcards to the American public, as well as two mainstays of the late-twentieth century diet—carbonated soda and hamburgers. The fair was lit by 7,000 arc lights and 120,000 incandescent lamps.

The fair’s symbol and centerpiece was an enormous Ferris Wheel, which, at 246 feet in height, was Chicago’s tallest structure. Fully loaded, the wheel could carry more than 2,000 people at a time, forty to sixty people in each of the thirty-six cars. One ride was two revolutions of ten minutes each. The fare for riding the Ferris Wheel was an enormous fifty cents, ten times the price of a merry-go-round. Still, 1.5 million people rode the wheel, and a few actually got married on it.

Apart from the Ferris Wheel, the fair’s most popular and profitable attraction were its sideshows. The Midway’s featured the “Street in Cairo” with its “hootchie-cootchie” dancing girls (who introduced Americans to belly-dancing).

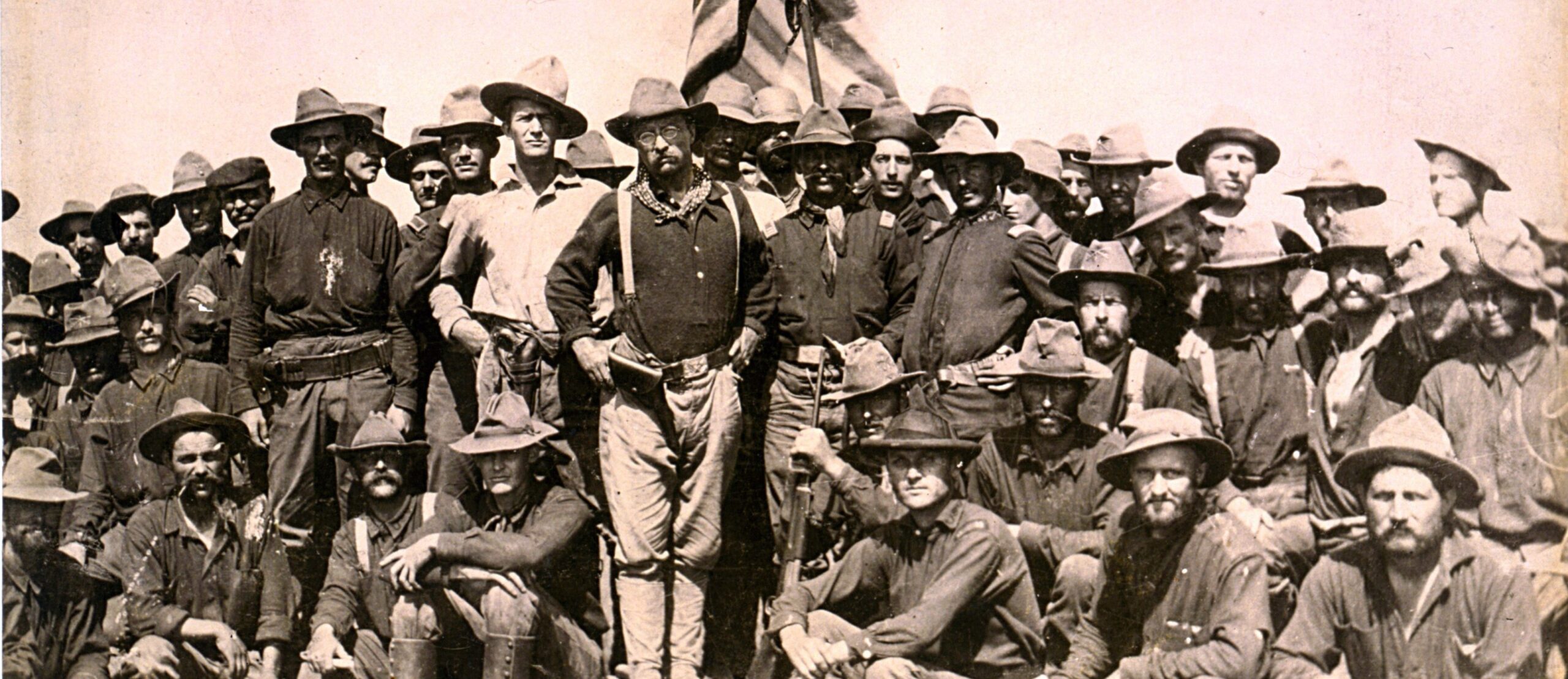

The fair attracted 27 million visitors, equivalent to one-third of the U.S. population at the time. Visitors included the fugitive slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, the social reformer Jane Addams, the ragtime composer Scott Joplin, the women’s rights leader Susan B. Anthony, and the historian Frederick Jackson Turner, who presented a famous paper on the disappearance of the American frontier and its consequences for the American character. Buffalo Bill Cody brought his Wild West show to town to take advantage of the crowds.

The fair reflected the racism of the time. The ethnological exhibitions of nonwhite peoples were arranged according to a sliding scale of humanities. Nearest to the White City were the Teutonic and Celtic races, then the Muslim and Asian worlds, and finally Africa and the American Indian.

Blacks were prohibited from constructing the fair or working in it. African American exhibits had to be approved by all-white screening committees before they could be displayed. In the end, the only official display presented the Hampton Institute’s educational program. A special day (Jubilee Day) was set aside for black visitors. Some black leaders, led by Ida B. Wells, called on blacks to boycott the fair. Others, like Frederick Douglass, were willing to accommodate themselves to the fair’s racism.

The fair took place at a time of upheaval and wrenching economic and cultural transformations related to mass immigration, labor violence, the farmers’ revolt, and racial tensions evident in the spread of lynching, voter disfranchisement, and legalized segregation.

The exposition offers a unique vantage point from which to view broader political, social, economic, and cultural transformations.

Why Have World’s Fairs Largely Disappeared?

Beginning with the first world’s fair in London in 1851, these expositions were major cultural events that captured the popular imagination. The Paris exposition of 1889 introduced the Eiffel Tower. The World’s Columbia Exposition of 1893 in Chicago brought the Ferris Wheel. The 1939 New York World’s Fair introduced television. Other fairs introduced such groundbreaking technologies as the telephone and the X-Ray machine and exhibited art, architecture, and design. These events showcased national achievements, highlighted new inventions, and introduced the public to visions of modernity. The tagline for the 1939 fair was “Building the world of tomorrow with the tools of today.”