Central America and the Caribbean

Policing the Caribbean and Central America

In 1904, Germany demanded a port in Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) as compensation for an unpaid loan. Theodore Roosevelt, who had become President after William McKinley’s assassination, told Germany to stay out of the Western Hemisphere and said that the United States would take care of the problem.

He announced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine:

Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the western hemisphere, the adherence of the U.S. to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of international police power.

Several recent developments led Roosevelt to declare that the United States would be the policeman of the Caribbean and Central America. Three European nations had blockaded Venezuela’s ports, violating the Monroe Doctrine’s unilateral declaration that Europe should not interfere in the Americas. Meanwhile, an international court in The Hague in the Netherlands had ruled that a creditor nation that had used force would receive preference in repayment of a loan. Further, Roosevelt had recently gained the right to build the Panama Canal. He believed that any threat to the canal threatened U.S. strategic and economic interests.

To enforce order, forestall foreign intervention, and protect U.S. economic interests, the United States intervened in the Caribbean and Central America some twenty times over the next quarter century—namely, in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Panama. Each intervention followed a common pattern: after intervening to restore order, U.S. forces became embroiled in the countries’ internal political disputes. Before exiting, the United States would train and fund a police force and military to maintain order and would sponsor an election intended to put into power a strong leader supportive of American interests. Unfortunately, the men who took power in many of these countries, such as Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua, Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, and Francois Duvalier in Haiti, established despotic rule.

Intervention in Haiti

In July 1915, a mob murdered Haiti’s seventh president in seven years. Vilbrun Guillaume Sam was dragged out of the French legation, where he had sought sanctuary, and hacked to death. The mob then paraded his mutilated body through the streets of the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince. During the preceding 72 years, Haiti had experience 102 revolts, wars, or coups. Only one of the country’s twenty-two presidents had served a complete term, and merely four died of natural causes.

With the European powers engaged in World War I, President Woodrow Wilson feared that Germany might occupy Haiti and threaten the sea route to the Panama Canal. To protect U.S. interests and to restore order, the president sent 330 marines and sailors to Haiti.

This was not the first time that Wilson had sent marines into Latin America. Determined to “teach Latin Americans to elect good men,” he had sent American naval forces into Mexico in 1913 during the Mexican Revolution. American Marines seized the city of Veracruz and imposed martial law.

The last marines did not leave Haiti until 1934. To ensure repayment of Haiti’s debts, the United States took over the collection of customs duties. Americans also arbitrated disputes, distributed food and medicine, censored the press, and ran military courts. In addition, the United States helped build about a thousand miles of unpaved roads and a number of agricultural and vocational schools, and trained the Haitian army and police. It also helped to replace a government led by blacks with a government headed by mulattoes. The U.S. forced the Haitians to adopt a new constitution which gave American businessmen the right to own land in Haiti. While campaigning for vice president in 1920, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had served as assistant secretary of the Navy in the Wilson Administration, later boasted, “I wrote Haiti’s Constitution myself, and if I do say it, it was a pretty good little Constitution.”

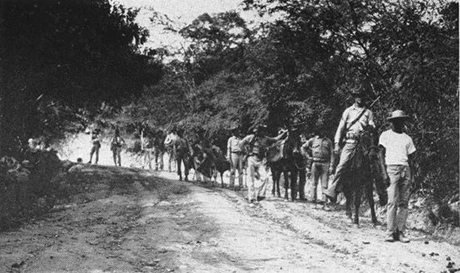

Many Haitians resisted the American occupation. In the fall of 1918, Charlemagne Péralte, a former Haitian army officer, launched a guerrilla war against the U.S. Marines to protest a system of forced labor imposed by the United States to build roads in Haiti. In 1919, he was captured and killed by U.S. Marines, and his body was photographed against a door with a crucifix and a Haitian flag as a lesson to others. During the first five years of the occupation, American forces killed about 2,250 Haitians. In December 1929, U.S. Marines fired on a crowd of protesters armed with rocks and machetes, killing twelve and wounding twenty-three. The incident stirred international condemnation and ultimately led to the end of the American occupation.

By that time, Roosevelt had changed his mind. In 1928, he had criticized the Republican administrations for relying on the Marines and “gunboat diplomacy.” “Single-handed intervention by us in the internal affairs of other nations in this hemisphere must end,” he wrote. After he became president in 1933, Roosevelt proclaimed a new policy toward Latin America. Under the Good Neighbor policy, he removed American Marines from Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua.

Historical Debates

Humanitarian Intervention

In 2005, the United Nations, with the support of nearly 200 nations, endorsed a principle known as “Responsibility to Protect.” This is the notion that when nations violate their citizens’ human rights, by committing atrocities or engaging in repression, other nations are empowered to intervene militarily to stop these violations.

Debates over humanitarian intervention have a long history in the United States. The argument began during the early nineteenth century, when many European peoples, including those in Greece and Hungary, sought to end rule by the Ottoman and Austrian empires. Louis Kossuth, a leader of the Hungarian struggle for independence, argued that the United States had a responsible to help beleaguered peoples to achieve independence as they had achieved their own independence with the help of France, the Netherlands, and Spain.

In 1898, President McKinley called for war with Spain to liberate Cuba from the “barbarities, bloodshed, starvation, and horrible miseries now existing there.”

From the U.S. intervention in Haiti in 1915 to the overthrow of Libya’s government in 2011, the United States has repeatedly justified military interventions on humanitarian grounds. The record of humanitarian interventions by the United States, however, has been very mixed.

The intervention in Haiti lasted for nineteen years and did not substantially improve the lives of the Haitian peoples. The intervention in Somalia during the early 1990s did not bring an end to factional fighting and the overthrow of the Libyan government in 2011 resulted in a failed state. In contrast, a U.S.-led intervention in a war in Kosovo in the Balkans in 1998 did bring the conflict to an end.

Also, U.S. decisions to intervene have been inconsistent. During the administration of President Bill Clinton, 800,000 people died during a conflict in Rwanda without a U.S. intervention; similarly, during the presidency of Barack Obama, the United States remained largely uninvolved in a conflict in Syria where an estimated half million people died.

History Through…

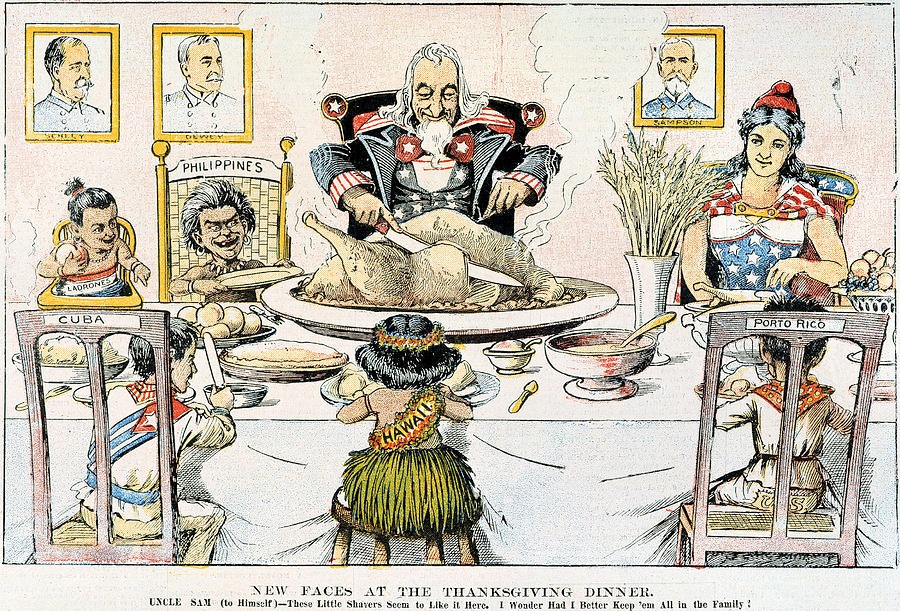

…Political Cartoons: “New Faces at the Thanksgiving Dinner”