The Philippines

The Philippine American War

The twentieth century began with the United States engaged in a bloody, but largely forgotten, war in the Philippines that cost hundreds of thousands of lives. The Philippine American War, fought from February 1899 to July 1902, claimed perhaps 250,000 lives and helped establish the United States as a power in the Pacific.

Today, few Americans are aware of the Philippine American War. The conflict was a sequel to the Spanish American War of 1898, which had been waged, in part, in support of Cubans fighting for independence from Spain. But it was also fueled by American desire to become a world power.

The Philippine American War prompted Mark Twain and other writers and artists to speak out against those who advocated American expansion. It fueled a bitter national debate over U.S. involvement overseas, a precursor to the outcry over the Vietnam War a half-century later. Some who opposed the occupation were motivated by racism, fearful that annexation of the Philippines would lead to an influx of non-white immigrants. One U.S. senator warned of the coming of “tens of millions of Malays and other unspeakable Asiatics.” Many, who considered the occupation immoral and inconsistent with American traditions and values, joined the Anti-Imperialist League.

The conflict helped popularize the concept of the “white man’s burden,” the notion that the United States and Western European societies had a duty to civilize and uplift the “benighted” races of the world. A U.S. senator from Indiana declared: “We must never forget that in dealing with the Filipinos, we deal with children.”

The Philippine American War also paved the way for migration from the Philippines. Shortly after the war, Filipino immigrants began arriving in the United States as students, U.S. military personnel, and farm and cannery workers. Today, there are more than three million Filipinos and Filipino Americans in the United States, making them one of the nation’s largest Asian communities.

On May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey entered Manila Bay and destroyed the decrepit Spanish fleet. In December, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States for $20 million. Mark Twain called the $20 million payment an “entrance fee into society—the Society of Scepter Thieves.” “We do not intend to free but to subjugate the people of the Philippines,” he wrote. “We have pacified some thousands of the islanders and buried them, destroyed their fields, burned their villages, and turned their widows and orphans out of doors.”

On June 12, 1898, a young Filipino, General Emilio Aguinaldo, had proclaimed Philippine independence and established Asia’s first republic. He had hoped that the Philippines would become a U.S. protectorate. But pressure on President William McKinley to annex the Philippines was intense. After originally declaring that it would “be criminal aggression” for the United States to annex the archipelago, he reversed his stance, partly out of fear that another power would seize the Philippines. Six weeks after Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay, a German fleet sought to set up a naval base there. The British, French, and Japanese also sought bases in the Philippines. Unaware that the Philippines were the only predominantly Catholic nation in Asia, President McKinley said that American occupation was necessary to “uplift and Christianize” the Filipinos.

On February 4, 1899, fighting erupted between American and Filipino soldiers, leaving 59 Americans and approximately 3,000 Filipinos dead. With the vice president casting a tie-breaking vote, a congressional resolution declaring the Philippines independent was defeated. American commanders hoped for a short conflict, but in the end, more than 70,000 would fight in the archipelago. Unable to defeat the United States in conventional warfare, the Filipinos adopted guerrilla tactics. To suppress the insurgency, villages were forcibly relocated or burned. Non-combatant civilians were imprisoned or killed. Vicious torture techniques were used on suspected insurrectionaries, such as the water cure, in which a suspect was made to lie face up while water was poured onto his face. One general declared:

It may be necessary to kill half of the Filipinos in order that the remaining half of the population may be advanced to a higher plane of life than their present semi-barbarous state affords.

The most notorious incident of the war took place on Samar Island. In retaliation for a Filipino raid on an American garrison, in which American troops had been massacred, General Jacob W. Smith told his men to turn the island into a “howling wilderness” so that “even birds could not live there.” He directed a marine major to kill “all persons…capable of bearing arms.” He meant everyone over the age of ten. Smith was later court-martialed and “admonished” for violating military discipline.

Aguinaldo was captured by a raid on the Filipino leader’s hideout in March 1901. The war was officially declared over in July 1902, but fighting continued for several years. The Philippine war convinced the United States not to seize further overseas territory.

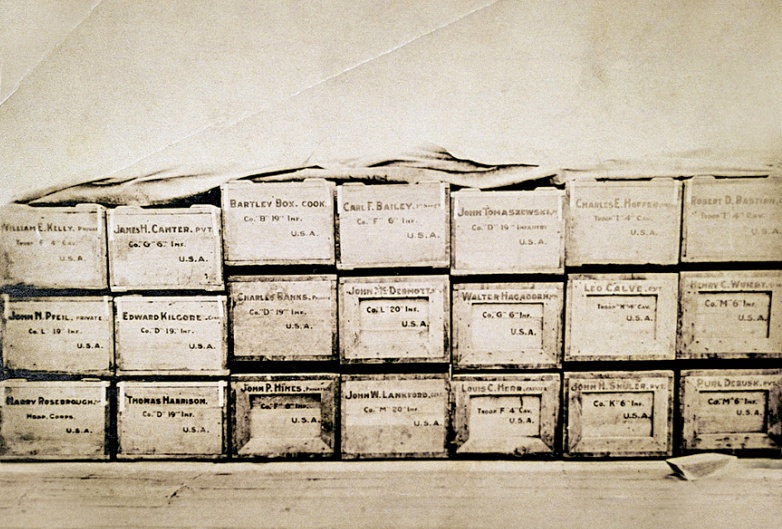

More than 4,000 American soldiers and about 20,000 Filipino fighters died. An estimated 200,000 Filipino civilians died during the war, mainly of disease or hunger. Reports of American atrocities led the United States to turn internal control over to the Philippines to Filipinos in 1907 and pledged to grant the archipelago independence in 1916.

U.S. leaders tried to transform the country into a showcase of American-style democracy in Asia. But there was a strong undercurrent of condescension. U.S. President William Howard Taft, who had served as governor-general of the Philippines, called the Filipinos “our little brown brothers.” The Philippines were finally granted independence in 1946.

Forgotten Lessons of History: The Philippines

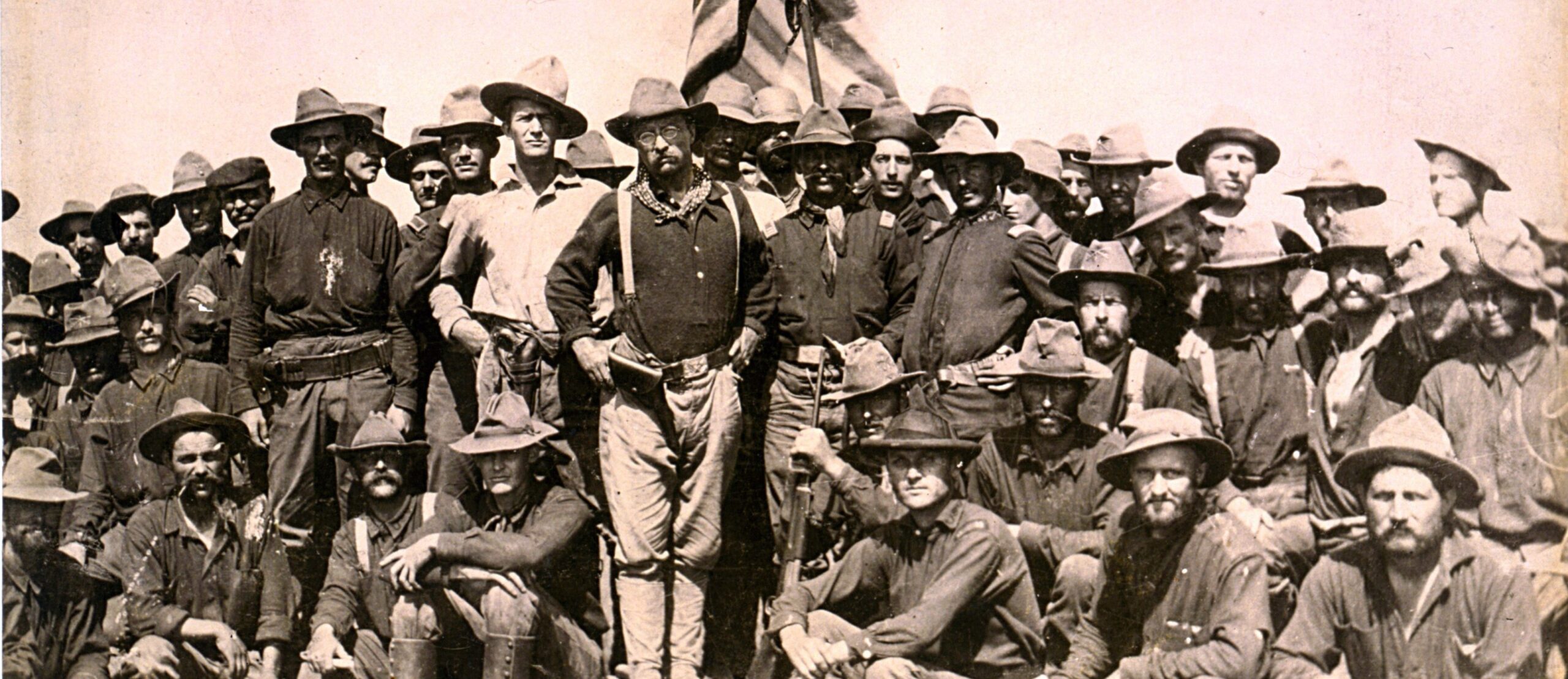

Why did the United States seek to conquer the Philippines during the Spanish American war when its ultimate goal was to dislodge Spain from Cuba? Some, including Theodore Roosevelt, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge,, and naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, wanted the United States to become a power across the Pacific, boosting trade with China and Japan. Many religious denominations were eager to spread Christianity across Asia. In a poem entitled “The White Man’s Burden,” Rudyard Kipling called on Americans to improve the condition of benighted pagans.

But many others opposed American involvement, regarding it as little more than imperialistic adventure.

It took just seven hours for the United States navy under Commodore George Dewey to dismantle the Spanish fleet. Unsure what to do next, President William McKinley said that he kneeled to God for help, and decided to “take them all and uplift and civilize and Christianize them.” Of course, most Filipinos were already Catholic.

A guerrilla conflict erupted, which lasted five years. By the end of the conflict, the Filipinos lost about 20,000 guerrillas, four times the number of American dead. As many as 250,000 Filipino civilians also died, largely as a result of epidemics of cholera and typhus.

One effect was to turn American leaders away from the any thoughts of permanently ruling the archipelago.

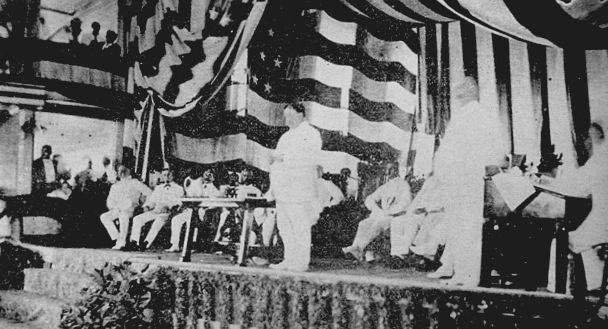

In 1904, after the war had been suppressed, William Howard Taft was appointed governor and proceeded to model the Philippines’s largest city, Manila, along U.S. lines, with broad boulevards, plazas, parks, and classically designed civic buildings. Two years earlier, the Filipinos elected a Parliament and soon the entire bureaucracy consisted exclusively of the native born.

Filipinos successfully lobbied Congress to be classified as American “nationals,” given free access to the United States, unlike all other Asians. Meanwhile, hundreds of American teachers arrived to establish a public school system, with English as the primary language of instruction, and train Filipino teachers. U.S. popular culture also swept the Philippines.

Why was it that the United States was able to exit the Philippines successfully, unlike later experiences in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq? In part, it was the brutal suppression of the resistance against U.S. forces, coupled with the trauma that accompanied the mass deaths due to epidemic disease. But it was also the decision to quickly shift governmental authority to the Filipinos themselves as well as the appeal of the U.S. educational system and of American culture and the existence of a safety valve, allowing Filipinos to enter the United States.

In stark contrast, in Vietnam it took seven years after the United States launched peace negotiations in 1968 for the Americans to fully withdraw from that country. Instead of achieving a negotiated peace in 1969, which might have allowed for an orderly withdrawal of American forces and of many South Vietnamese allies, the sudden collapse of the South Vietnamese military in early 1975 resulted in a chaotic situation, with thousands of former government officials, military officers, and members of the intelligentsia sent to re-education camps, millions of city dwellers were forced into rural areas, and a million South Vietnamese “boat people” fleeing the country often spending years in refugee camps in neighboring countries.

In Afghanistan and Iraq, the United States was often regarded as an intrusive and alien presence. Those societies were, in turn, deeply divided, in which struggles over politics, religion, and ethnic boundaries turned violent. The United States largely failed in its efforts to create an inclusive government that respected the interests of Afghanistan’s and Iraq’s sub-communities.