The Election of 2016 and the Fate of the White Working Class

The Election of 2016 and the Fate of the White Working Class

The election of Donald J. Trump to the presidency was one of the most surprising events in the history of American politics. A survey from the Princeton Election Consortium, released just before the election, gave Hillary Clinton a 99 percent chance of winning. Trump’s victory ran counter to virtually every forecast, which put Secretary Clinton’s chances of winning in the 77 to 99 percent range. Clinton won the popular vote, receiving roughly 3 million more votes than Trump. But he received more electoral votes in capturing the presidency.

The polls significantly underestimated Trump’s support in the Midwest, the Rust Belt (the area of declining manufacturing industries), and among white evangelical Protestants and especially middle-aged and older white Americans without a college degree.

The election suggested that economic anxiety and anti-establishment anger were far stronger than many political commentators imagined.

Many measures of economic hardship—poverty, joblessness, falling wages, foreclosures, and bankruptcies—had improved markedly since the Great Recession began in 2008. But in 2017, half the nation’s counties still had fewer jobs than in 2008.

Meanwhile, economic anxiety—including concerns about economic opportunity, retirement or potential layoffs and fears for their children’s prospects persisted, especially among the white working class. Trump support was especially strong in areas where jobs were especially vulnerable to outsourcing or automation, where the number of jobs available to workers without a bachelor’s degree was falling, and where more residents were receiving disability payments.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, candidate Trump’s stance on immigration and race provoked widespread protests as an appeal to bigotry. Capitalizing on worries about job loss, resentments over affirmative action, and fears of crime and terrorism, candidate Trump called for the building of a physical wall along the US-Mexican border to be paid for by Mexico, immediate deportation of undocumented immigrants, a ban on immigration from certain predominantly Muslim nations, and even ending the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship (that is, that principle that anyone born in the United States automatically becomes a U.S.citizen, with all Constitutional rights).

He also used inflammatory and racially charged language during the campaign, for example, referring to undocumented Mexican immigrants as rapists. This represented a sharp turn-around from the Obama administration’s emphasis on protecting the rights of African-Americans, Latinos, Muslims, and people who are gay or transgender and deporting only undocumented immigrants who were convicted criminals, terrorism threats, or who recently crossed the border. Unlike the Obama administration’s praise for the Black Lives Matter movement, which protested against shootings of African Americans by law enforcement officers, Trump praised police.

The 2016 election suggested that the nation was more polarized and divided politically, demographically, and geographically than it had been in many years. The election laid bare a fault line along the lines of education and economics.

In many parts of the country, the kinds of industries that employed non-college graduates were contracting, undercut by automation and foreign competition. Those jobs that remained, such as in the retail sector or home health care aids, paid little. In many rural areas, college graduates were fleeing, seeking access to higher pay.

In increasing numbers, middle-aged white Americans were experiencing rising rates of suicide and alcohol or drug overdoses, marital breakup, and mental health problems. In Appalachia, life expectancy was below that in Bangladesh.

None of this should be surprising. Millions of manufacturing jobs have disappeared, and no reliable replacements have emerged. Wages have stagnated, and economic mobility has fallen. College costs have risen rapidly, and many workers have no source of retirement income apart from Social Security.

At the same time, the institutions that had buttressed working class life—manufacturing, the church, unions and stable marriage—were eroding.

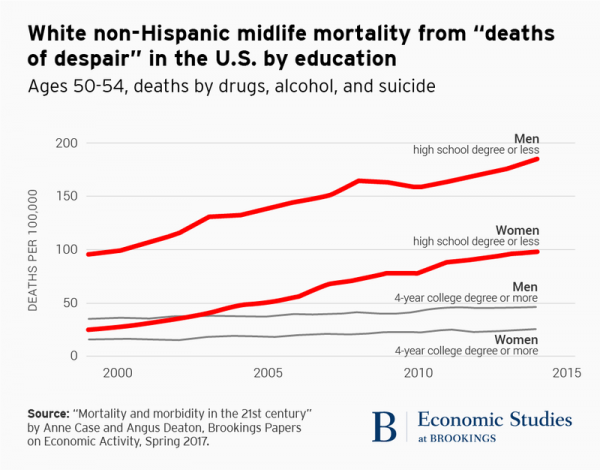

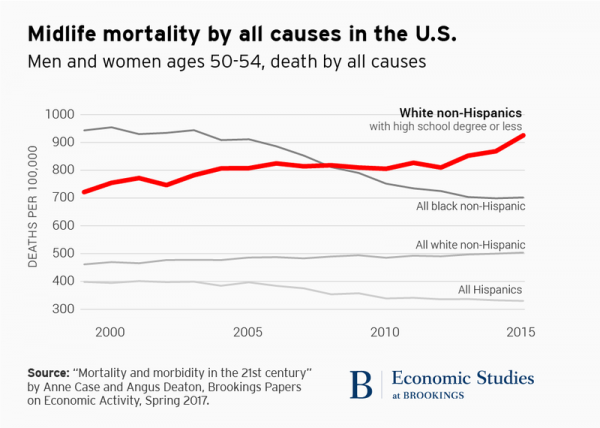

Despite advances in medical care, the death rate among middle class white Americans has risen steeply since the late 1990s. Driving this trend are people without college degrees. While blacks and Latinos have seen improvements in death rates, drug overdoses, alcoholism, and suicide have increased the mortality rate among non-college educated whites.

Although, on average, African Americans and Hispanic Americans experienced greater economic hardship than non-college educated whites, they were doing better than their white counterparts in terms of life expectancy, rates of chronic illness, and deaths from suicide or substance abuse.

Two leading economists attribute this to the erosion of institutions that provided stability for the working class for much of the twentieth century: manufacturing, churches, labor unions, and stable marriages.

The Populist Impulse

The word Populism is much in the news. Political figures as diverse as Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, an avowed socialist, are labeled as populists. Populism is a label that has been applied to a wide range of political movements, on the left, the center, and the right.

Sometimes, the term is a synonym for anti-establishment. At other times, it is deployed as an epithet. Populists are often dismissed as angry, even demagogic, as illiberal, bigoted, paranoid, and xenophobic, as prone to naïve, unsophisticated panaceas. Hitler, Mussolini, and Putin have all been called Populists.

But Populism generally has its roots planted in economic distress and cultural upheavals that have undermined a group of people’s way of life.

The term “Populist” dates to the late nineteenth century, when two very different groups–western and southern farmers in the United States and the anti-Czarist Russian intelligentsia – adopted the term. Populists claim to speak for the people. The definition of the people, however, tends to be vague

In the United States, there are several Populist traditions. One, which dates back to Thomas Jefferson, represented an alliance between the South and West against Northeastern banking and commercial interests. This anti-monopoly, anti-banking tradition was particularly powerful during the presidency of Andrew Jackson. It gained new life toward the end of the nineteenth century, when debt-ridden farmers, in alliance with urban workers and small town business people, organized against corporate cartels and oligopolies, debt peonage, and the degradation of labor.

Especially during the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal revived the anti-monopoly tradition by seeking to break up concentrations of power. Giant utility holding companies were broken up. Commercial and investment banks were separated. Chain stores were barred from using predatory pricing to put small stores out of business. Anti-trust laws were used to prevent consolidation of many industries and government regulation controlled pricing in such areas of the economy as trucking, airlines, and telecommunications.

Another Populist tradition was rooted less in economic grievances than in a reaction to cultural transformation. It represented a response to rapid urbanization, immigration, and secularization, as well as profound changes in women’s roles.

What Populists share in common is a distinct rhetorical style and an ideology that pits the people against corrupt elites. Populists view themselves as the champions of ordinary people. Their goal is to transfer power to the people, where it belongs.

Populists are angry at a corrupt establishment. Populists regard government as unresponsive to the people’s grievances and beholden to moneyed interests. Populists also believe that ordinary people are victims of exploitation: by profit seeking corporations, privileged elites, and self-serving politicians.

But Populism sometimes has a nasty side. “The people” tend to be defined narrowly, in ways that exclude those who do not share a common religion or ancestry. If Populism is generally driven by economic and political grievances, it has sometimes been fueled by an animus directed against Catholics, Jews, or immigrants. Populists tap into genuine fears of economic stress, stagnating living standards, and of cultural displacement.

In the 2016 presidential campaign, both Donald Trump, a real estate tycoon, and Bernie Sanders, an independent senator from Vermont and an avowed socialist, tapped into a strong anti-establishment sentiment. Despite stark differences in their attitudes toward immigration, government regulation, healthcare, and other issues, the two candidates symbolized the spread of Populist sentiments.

“Why Don’t More Americans Vote?”

Listen to the podcast entitled, “Why don’t more Americans vote?”

In the 2017 presidential election, 59.7 percent of eligible voters cast their ballots. That compares to 87 percent in Belgium, 83 percent in Sweden, and 80 percent in Denmark. Among developed countries only Switzerland trails the United States. There, less than 39 percent of the voting age population cast a ballot. In many countries, voter registration is mandatory, but not in the United States. Roughly 30 percent of adult US citizens fail to register—compared to 91 percent in Canada and 99 percent in Japan.

The Biden Presidency

A former vice president and senator, and a three-time candidate for the presidency, Biden ran in 2020 as a moderate alternative to his Democratic opponents, strongly opposing ideas like Medicare for all and defunding the police. He held out the promise of helping the country recover economically and psychologically from the pandemic that killed 1.2 million Americans, calming the country’s intense partisan and ideological divisions,

He had experienced terrible personal tragedies, including the death of his first wife and a son in a car accident and the death of another son from a glioblastoma brain tumor.

His margin of victory in the 2020 election was extremely narrow. It was followed by an assault on the US Capitol by thousands of Trump supporters, egged on, in part, by the then president’s false claim that the election had been stolen.

Once in office, the new president faced a host of serious challenges. One was surging inflation, which peaked at 9 percent in June 2022, which was partly a response to snarled supply chains and pent-up consumer demand.

Still, with the Senate divided 50-50, he succeeded in enacting the greatest expansion of the federal government since Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society. Congress enacted a $1.9 trillion Covid relief bill in March 2021 followed by the Inflation Reduction Act, which provided $1 trillion in green subsidies, the Chips act to promote the manufacture of semiconductors, and bills to repair the nation’s crumbling infrastructure.

During his single term in office, US oil production soared to record levels as did energy from renewable sources, including solar and wind power. He also released substantial amounts of oil from the country’s strategic petroleum reserves, helping to blunt inflation.

With a series of landmark bills, his administration sought to restore American manufacturing, prompting a boom in factory construction, with much of the new spending on production of semiconductors and batteries.

To his conservative critics, President Biden had promised to be a moderate who would shun extremism, govern from the center, and unite the country after the divisive Trump years, but once in office pursued much of the agenda advanced by his campaign’s opponents, Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. He forgave substantial amounts of student debt.

In the realm of foreign policy, his decision to withdraw US forces from Afghanistan was quickly followed by the collapse of the American-back Afghani government and the return of the Taliban to power. Whether the withdrawal could have been better handled remains the subject of debate, but as a result, his popularity sagged and never fully recovered.

Shortly afterward, Russia launched an unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, a former Soviet republic. The Ukrainians fought back, and with supplies provided by NATO, including antitank missiles, tanks, precision artillery, and jet fights, was able to resist the attempted conquest of their country, though at a terrible cost in lives and property destruction. The Biden administration’s success in forging unified Western response to the Russian invasion is, without a doubt, a remarkable feat of diplomacy.

Following President Trump’s example, President Biden took a tough line toward China, slapping tariffs on Chinese manufactured goods and imposing export controls on advanced semiconductors. To check China’s territorial ambitions in Asia. His administration signed agreements with India, strengthened ties with Japan and Australia, and rekindled America’s alliance with the Philippines.

Conflict in the Middle East also dominated the Biden presidency. Following an October 2023 attack from Gaza that left 1,200 Israelis dead and hundreds taken captive, the Israeli response threatened to touch off full-scale regional war, pitting the Jewish state against Iran and its proxy forces in Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen. The Israel-Gaza conflict also provoked bitter clashes in the United States, where protests against the war and establishment of encampments on mainly elite campuses prompted investigations led by House Republicans.

Culture war issues over abortion, affirmative action, and transgender rights also roiled the country, with the Supreme Court, overturning Roe v. Wade and ruling that the states were free to establish their own abortion policies; rejecting affirmative action in college admissions as a violation of equal rights; and the administration’s proposals about transgender rights in educational settings provoking a strong backlash from legislators in the “red” states.

The administration could count many successes. The American economy rebounded from the pandemic faster than any other country, with unemployment falling to less than 4 percent. After peaking at 9 percent in June 2022, the inflation rate fell to less than 3 percent by mid-2024. Violent crime, after spiking during and shortly after the pandemic, plummeted.

Nevertheless, despite these successes, anti-Biden sentiment was intense. Many voters were angry over rising prices, high interest rates, and a substantial influx of undocumented immigrants across the nation’s southern border. Many thought he was too old to remain as president.

In 2024, the Democratic party, fearing a resounding election defeat, pressured him to end his reelection campaign. Facing a loss of donor support, he backed his vice president Kamala Harris, for the presidency.

How President Biden’s legacy will be evaluated, only time will tell. But it seems fair to say that his was a transformational presidency, which brought to an end the “neoliberal” economic consensus that emphasized free trade and limited government interference in industry. With his administration’s emphasis on climate change, anti-trust enforcement, reindustrialization, international agreements, and industrial policy – to support strategically-important industries, like semiconductors – he sought to strengthen the role of the federal government in American life, to shore up the nation’s safety net, and forge an international coalition to resist authoritarian governments that threatened their neighbors.

He also helped maintain the unify of the Democratic party in the face of deep policy divisions and saw the United States emerge from the pandemic in better economic shape than any other developed country.

How his presidency will be viewed will hinge, to a great degree, on what happens next. Will the public mood brighten or will the country remain deeply riven? Will conflicts spread across the Middle East and will tensions in the Far East intensify? Will the United States successfully address its current challenges, including very steep housing costs, the difficulty in building and repairing infrastructure (including its roads, public transportation system, and power grids), and the threats posed by climate change?

The full impact and historical significance of a presidency is not fully understood or appreciated into well into the future. Contemporary judgments of political figures and their legacies are often subject to revision as events unfold and new information comes to light.

The long-term effects of Biden’s economic policies, including his response to inflation and efforts to boost job growth, will not be fully evident for years. Future economic conditions will influence how these policies are perceived.

The outcomes of current international situations, such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict or U.S.-China relations, will significantly impact assessments of Biden’s foreign policy approach. Similarly, the effectiveness of Biden’s climate policies will be judged based on future environmental conditions and global climate action.

The success or failure of Biden’s initiatives in areas like infrastructure modernization and clean energy will be more apparent in the future. Crises or opportunities that arise after Biden’s presidency may retroactively impact perceptions of his leadership and decision-making.

Evaluating a presidency requires historical distance: As time passes, a more holistic view of Biden’s presidency will emerge, divorced from immediate political tensions.