Emerging Threats

Emerging Threats

Predicting the future is a mug’s game, a game you are likely to lose no matter the odds. Virtually no one anticipated the Great Depression or the Stock Market Crash, or, much later in time, the Great Recession that began in 2008, or the rise of terrorist groups such as Al-Qaeda and ISIS.

No one can predict the future.

And yet, it can be helpful to identify certain geopolitical trends that pose tactical and strategic challenges. Only by imagining the future can we prepare for what might lie ahead.

These scenarios vividly illustrate how recent developments in technology, demographics, economics, and politics can expose challenges that may eventually materialize.

Here are a few possibilities:

- Tensions between two nuclear-armed states where a single miscommunication or technical failure could lead to a missile launch. India, Pakistan, Israel, Iran, and North Korea are among the states for which nuclear weapons play a central role in their military strategies. In the midst of an international crisis, one of these countries might turn to such weapons.

- The migration of hundreds of thousands of people from areas where they face political violence or environmental devastation. Already, a desperate tide of people is flowing into Europe from North Africa and the Middle East, producing a great deal of political tension and a surge in ethnic, religious, and political nationalism across the West. Nearer the United States is migration from Guatemala, El Salvador, Venezuela, and Honduras

- A miscalculation by a major power that spirals out of control. China is currently expanding its military and economic presence in the South China Sea, threatening to provoke responses from the United States and its east Asian allies that could, potentially, lead to a confrontation.

- The breakdown of a nuclear-armed nation state that might loosen control over nuclear weapons. Should a major nation, such as Pakistan, disintegrate, it is imaginable that central control over its nuclear stockpile could break down.

- The proliferation of nuclear weapons as nations arm themselves in the face of potential foreign threats. Japan, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and Turkey are among the states that might develop nuclear weapons if they doubt the United States’ willingness to protect them.

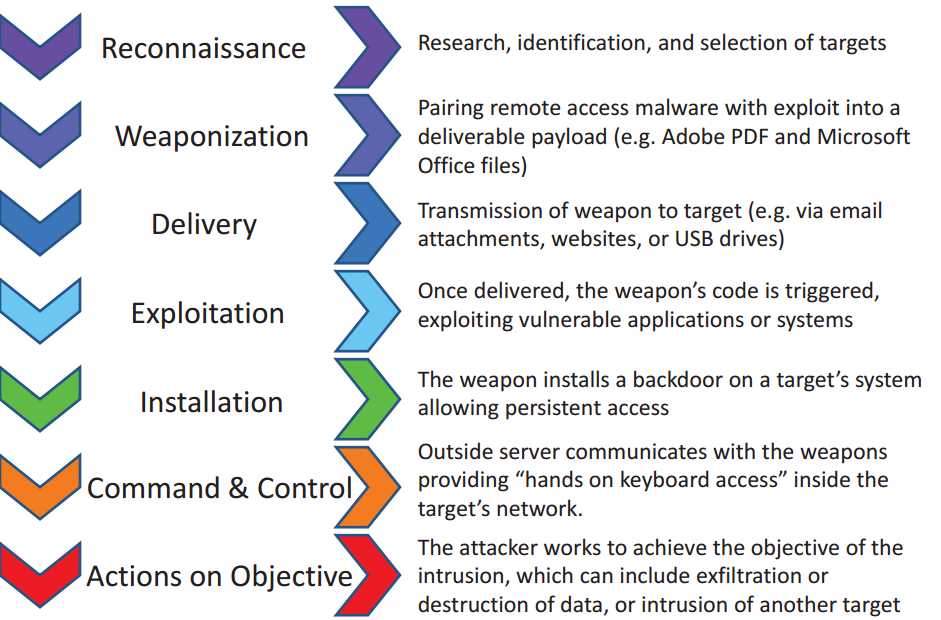

- A cyberattack that undermines banking or the electrical grid or other utilities. Small cyberattacks, such as one that triggered Dallas’s emergency sirens and hacking have revealed this country’s vulnerability to malicious software and other Internet threats, which could potentially compromise financial transfers or health care or transportation, communication, or electrical and water systems.

- An accident where a faulty reading or hardware failure might provoke a nuclear response. Spin the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Wheel of Near Misfortune, which identifies instances where the world only narrowly avoided a nuclear strike.

- A global pandemic that crosses borders. Ebola and Zika are two examples of diseases that pose spread rapidly as a result of global trade, climate change, and ecological disruption.

- The decline of post-World War II internationalist values that prioritized international cooperation and freedom of trade and migration. The Cold War system of alliances propped up many weak and newly independent states with money to build infrastructure and to control their borders. In large parts of the world there are now areas without a single central power. Rather, we see militias, pirates, and terrorist and criminal organizations filling the vacuum.

- Terrorist acts shut down a major city. Attacks in Boston, London, Manchester, and Paris might turn out to be smaller examples of greater challenges in the future.

In certain respects, the international environment seems more perilous than at any time since the height of the Cold War. Challenges include insurgent groups in the Middle East, tensions over Iran’s efforts to extend its influence across the region, North Korea’s ambitious nuclear program, China’s rise to global power, Russian meddling in U.S. and European elections, secessionist impulses in Europe and elsewhere, the impact of Syria’s civil war, the flow of heightened refugees in response to disorder especially in the Middle East and North Africa, and various cyber threats.

Instead of focusing on a single threat — the situation during the Cold War, when the focus was on the Soviet Union — the United States worries about multiple threats. The number and potential magnitude of these threats is uncertain, breeding deep anxieties and uncertainty about how best to respond.

Some worry that the United States is overextended. As of 2018, the country had been at war continuously since the attacks of 9/11 and now has just over 240,000 active-duty and reserve troops in at least 172 countries and territories. American forces are actively engaged not only in the conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen, but also in Niger and Somalia, as well as Jordan, Thailand and elsewhere.

In addition, U.S. forces remain deployed in Japan (where 39,980 troops are currently based) and South Korea (23,591) to defend against North Korea and China, if needed, along with 36,034 troops in Germany, 8,286 in Britain and 1,364 in Turkey — all NATO allies. There are also 6,524 troops in Bahrain and 3,055 in Qatar, where the United States has naval bases.

With the world so uncertain, the United States must pay attention to a multiplicity of potential threats.