Revolutions in American Life

The First Amendment

Freedom of speech is a point of contention in the contemporary United States.

in 1989, the Supreme Court ruled in Texas v. Johnson that the state could not punish an individual for burning the American flag. The Court ruled that flag burning was symbolic speech, protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution.

In recent years, a number of college campuses have attempted to restrict speech regarded as hateful or hurtful. At Fordham University in 2012, the Republican Club wanted to invite the conservative pundit Ann Coulter to speak and was not allowed to do this. In 2013, the New York City police commissioner was shouted down at Brown University. In 2016, the Israeli mayor of Jerusalem was shouted down at San Francisco State.

Smith College withdrew an invitation to Christine Lagarde, the first woman to head the International Monetary Fund, to speak to the graduating class. Scripps College effectively withdrew columnist George Will’s invitation to speak after the invitation generated controversy.

A 2015 survey of some 800 undergraduate students, sponsored by the William F. Buckley Jr. Program at Yale, found that 51 percent of students favor their school having speech codes and trigger warnings. Nearly one-third of the students could not name the constitutional amendment dealing with free speech. And 35 percent said that the First Amendment does not protect “hate speech.”

One way that the United States is unique is in its stringent protections against government restrictions of free speech and a free press. No other advanced society allows individuals the right to voice their beliefs without government approval or oversight. American law protects free speech more often, more intensely, and more controversially than is the case anywhere else in the world, including democratic nations such as Canada, England, or Germany.

The spirit of the First Amendment was perhaps best expressed by an English philosopher named John Stuart Mill. Mill argued in favor of a marketplace of ideas in which the best answer to bad ideas lies in better ideas.

Today, the First Amendment prohibits the government from censorship of a publication prior to publication.

Yet the protections for free speech and a free press are relatively recent developments. In the past, the government censored speech and publications by invoking obscenity, blasphemy, and sedition laws. Newspapers and magazines were frequently restricted.

The nation’s first controversy involving freedom of speech and of the press erupted in 1789, when the nation was engaged in a conflict with France. The Federalist party which controlled the executive, legislative and judicial branches of the government, made it a crime to publish “any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings…with intent to defame” the government, the Congress, or the President.” Several newspaper publishers were jailed under the Sedition Act.

A future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, John Marshall, then a Federalist member of Congress, declared that the First Amendment meant only the “liberty to publish, free from previous restraint”—that is, free from any licensing requirement or from censorship prior to publication. James Madison, who had drafted the Bill of Rights, rejected that argument. He declared that even speech that creates “a contempt, a disrepute, or hatred [of the government] among the people” should be tolerated because the only way of determining whether such contempt is justified is “by a free examination [of the government’s actions], and a free communication among the people thereon.”

It was not, however, until the First World War that the Supreme Court began to hear a range of cases dealing with freedom of speech and freedom of the press. In March 1919, in Schenck v. United States, the United States Supreme Court affirmed the conviction of Socialist Party official Charles Schenck under the 1917 Espionage Act which made it a felony to “cause, or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States, or…[to] willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the United States.” In the opinion written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., the Court held that speech is not protected if “the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about…substantive evils.”

In November 1919, in Abrams v. United States, the United States Supreme Court affirmed the conviction of Jacob Abrams under the 1918 Sedition Act for publishing pamphlets criticizing the war. The Sedition Act made it illegal to “willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States, or the Constitution of the United States.” However, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, the author of the Schenck opinion, issued a dissent, arguing that not all anti-government speech presents a clear and present danger and Congress “certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country.”

Even today, the right to free speech and freedom of the press is not absolute. The courts have upheld certain exceptions:

- Incitement: The government has the power to restrict speech that would result in imminent unlawful, violent conduct.

- Intentional false statements of fact.

- Obscenity: If a work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

- Child Pornography: Because it involves hard to children.

- Threats: That can be reasonably perceived as threatening violence.

- Fighting words: Face-to-face insults that are likely to result in violence.

- Plagiarism: Which violates the intellectual property rights of another person.

- Commercial Advertising: Which may not be misleading.

Revolutions in American Life

The past century has been a century of recurrent revolutions in every facet of life—in medicine, science, and technology, to be sure, but perhaps even more momentously, in gender roles, the life stages, and attitudes.

The past century has also been a century of conflict and struggle. The fundamental struggles were not between economic classes or geographical regions, but over values, as Americans waged a cultural civil war over the definition of what kind of country the United States is.

Key battlegrounds in this cultural civil war have involved civil liberties, foreign policy, gender, immigration, race and ethnicity, and the size and role of government. This cultural civil war has pitted political conservatives against political liberals, but also Fundamentalists, Pentecostals, and Evangelicals against religious liberals.

One revolution was a revolution in language and thought. Among the most far-reaching developments in human understanding came with the growing impact of psychology. The way we think about ourselves—the unconscious, the subconscious, defense mechanisms—was profoundly influenced by the growing influence of psychology.

Another revolution took place in Americans’ diet. Processed and frozen foods became staples of the diet. So, too, did convenience foods and fast food, along with ethnic foods. And food increasingly became a class marker, with the more affluent eating quite different foods than those who are poorer.

Yet another striking revolution has involved shifting notions of fashion and beauty. Everyday dress became far more casual than in the past.

The triumph of consumerism, too, represented a revolution in American life. It was over the past century that the United States became the world’s first consumer society, fueling extraordinary economic growth. Aggressive advertising and the ready availability of consumer credit allowed consumerism to thrive.

Opportunities for consumer spending multiplied over the past century. The car was among the first and most significant consumer good, providing mobility and privacy, but also contributing to congestion, stress, and pollution. During the early post World War II period, consumerism brought families together: But increasingly consumerism divided and isolated Americans, and became a crucial symbol of class divisions. This country produced some of the world’s sharpest critique of consumerism, through cultural critics, such as Thorstein Veblen, Rachel Carson, and Ralph Nader. But the United States remains the exemplar of a consumer society.

A revolution in the life course constitutes yet another revolution in American life. Americans became acutely sensitive to class and racial differences in childhood. They also became much more attentive to risks to children’s health or well-being, including sexual and gender abuse. Over the course of the past century, new life stages arose: adolescence, the teenager, young adulthood, a period between adolescence and full adulthood, and the young old and the old old.

There was also a revolution in how and where Americans live. Today, more Americans live in suburbs than in urban and rural areas combined. During the twentieth century, suburbanization was motivated not only by a dream of home ownership but by a quest for security and a sanctuary from class, racial, and ethnic issues. Suburbanization was fueled by cheap energy, by government transportation and housing policies, land speculators, developers, real estate brokers, and banks and savings and loans. Especially important were accelerated depreciation, federal highway funds, and cheap farmland that encouraged fringe development.

Although clichés about suburbia remain integral parts of popular culture, classic urban problems—crime, congestion, corruption, ethnic tension, drug use, school violence—have now reached the suburbs. Today, the suburbs have become democratized. They include apartments as well as single family homes. Their residents include Asian Americans, blacks, and Hispanics as well whites. The drive for profits has transformed suburbs into mini-cities—but without planning, without downtowns, and without many urban amenities. Today, many suburbs suffer from sprawl, overdevelopment, inadequate public transportation, and a host of other problems.

Another shift in how Americans live involves the rise of the Sunbelt and the decline of the industrial Midwest.

But of all the revolutions in American life, three stand out: A revolution in government, in America’s role in the world, and in attitudes toward freedom.

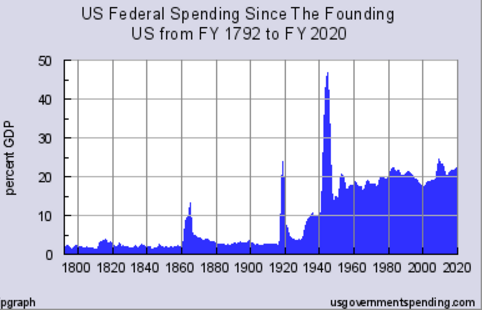

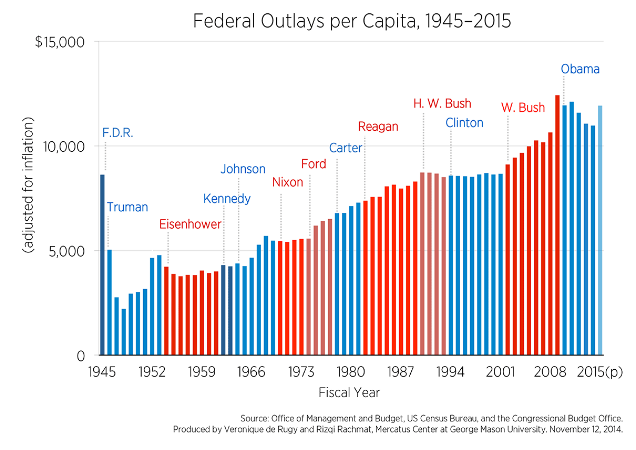

Government was America’s number one growth industry in the twentieth century—bigger than cars, computers, or even health care. Over the course of the twentieth century, both the state and federal governments expanded their functions, expenditures, and developed a far-flung administrative apparatus.

Americans are of two minds about government. Americans want limited government and low taxes and also want an activist government and more benefits.

The growth of government is not only a function of increased spending or government employment, but of increasing legal and bureaucratic power. Executive orders and administrative agency decisions provided new ways for government to exercise authority. Meanwhile, power has shifted from states and localities to the federal government and from Congress to the president and the executive branch.

The growth of government has not been gradual or incremental. The paramount reason government has grown is in response to crises—real or imagined. These included wars and economic upheavals and international tensions. With each crisis, government has gained new powers over social and economic affairs.

Also contributing to the growth of government were the pressure of interest groups, voter demands, and readiness of public officials to do something for their constituents.

To sustain its broad new functions, government spending rose. In 1916, federal spending per person was $83.60. Today, the figure is $25,735.

Of all the changes that have taken place in government in the twentieth century, the most dramatic is the concentration of power in the executive branch. Whether we regard the president as a white knight, a potential savior, or a villain and potential tyrant, the executive branch acquired powers unimaginable in the nineteenth century.

For much of the nineteenth century, the presidency was largely passive. The Constitutional separation of powers was taken seriously. The president’s job was to execute the laws passed by Congress.

Congress took the lead in formulating public policy.

There was outright hostility to the idea that a president should initiate legislation. Presidents did not address Congress in person. Their public speeches rarely contained policy pronouncements. It was commonly assumed that a president should not veto legislation to express policy preferences.

Even in the realm of foreign policy, presidents were restrained

There were, to be sure, exceptions, including Lincoln’s initiatives during the Civil War. Yet even Lincoln felt he needed the retroactive approval of Congress.

It was not until the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson that the presidential role began to change. According to Progressives, the president supposedly better represented the public interest than did Congress

During the early years of the twentieth century, the president began to monopolize power rather than share it with Congress: drafting a budget and administering government agencies. Administrative rulemaking replaced legislation as the major way that government intervened in society.

But it would be FDR and the New Deal that would institutionalize the supremacy of the executive branch. FDR, more than any preceding president, established the practice of advocating particular policies and winning political support for them.

Of course, war was essential to creating the Imperial Presidency. After World War II, presidents substituted executive agreements for treaties requiring Senate approval. Even more important, presidents gained the power to wage undeclared war, despite the fact that Congress is the sole branch of government empowered by the Constitution to declare war.

The Cold War gave the president wide latitude in the exercise of power in the name of anti-Communism. It also generated an acceptance of indiscriminate involvement across the globe. President Truman vastly expanded the president’s war-making powers. President Eisenhower substantially increased America’s international commitments, including a network of agreements with nearly fifty nations. President Kennedy, in the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis, acted without consulting Congress. President Johnson took the position that a president could deploy American military forces abroad without formal Congressional approval

No president went further than Richard Nixon in concentrating powers in the presidency. He refused to spend funds that Congress had appropriated. He claimed executive privilege against disclosure of information on administration decisions. He refused to allow key decision makers to be questioned before congressional committees; he reorganized the executive branch and broadened the authority of new cabinet positions without congressional approval. And during the Vietnam War, he ordered harbors mined and bombing raids launched without consulting Congress.

Watergate brought a temporary end to the “imperial presidency” and the growth of presidential power. Over the president’s veto, Congress enacted the War Powers Act (1973), which required future presidents to win specific authorization from Congress to engage U.S. forces in foreign combat for more than ninety days. Under the law, a president who orders troops into action abroad must report the reason for this action to Congress within 48 hours.

If Watergate and Vietnam brought a temporary end to the imperial presidency, since the early 1980s, presidential power has reasserted itself. This can be seen in the reassertion of the president’s:

- War-making and treaty-making powers

- In the growth of presidential authority over surveillance, intelligence, and domestic security

- In expanded claims of executive privilege and confidentiality

- In growing discretion in negotiating trade agreements

- In a declining willingness to consult and share information with Congress

Alongside the growth of government came a revolution in America’s role in the world. Today, military spending by the United States is larger than in the next ten countries combined. The United States is the only country capable of projecting an army across the globe

How did the United States become the world’s policeman? What motivates American foreign policy?

- Economics: To ensure opportunities to invest, find markets, acquire raw materials, and trade freely.

- A sense of national mission: To advance democracy, ensure stability, protect national security, and channel nationalism and revolutionary agitation in acceptable directions.

Of all the revolutions over the past century, the most radical is a revolution in American ideas about freedom.

The freedoms that Americans expect today are much more expansive than those they expected in the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries. In the past, freedom meant freedom of religion, rule of law, and the right to democratic self-government. In the twenty-first century, freedom includes the right to certain entitlements—to aid in response to old age or unemployment or destitution—to opportunity through educati, and, perhaps most important of all, to self-realization, evident in the struggle for women’s rights, gay and lesbian rights, and the rights of the disabled.

The past century witnessed an unprecedented revolution in women’s rights and civil rights, in civil liberties, and the rights of criminal defendants. Especially noteworthy is the invention of a right to privacy and to gender equality and sexual freedom.