Race and Progressivism

Along the Color Line

The period late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries represented the low point of American race relations. Nine-tenths of African Americans lived in the South, and most supported themselves as tenant farmers or sharecroppers. Most Southern and border states instituted a legal system of segregation, relegating African Americans to separate schools and other public accommodations. Under the Mississippi Plan, involving the use of poll taxes and literacy tests, African Americans were deprived of the vote. The Supreme Court stripped the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of their meaning, especially in the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, which declared that racially “separate but equal” facilities were permissible under the fourteenth Amendment. Each year approximately a hundred African Americans were lynched.

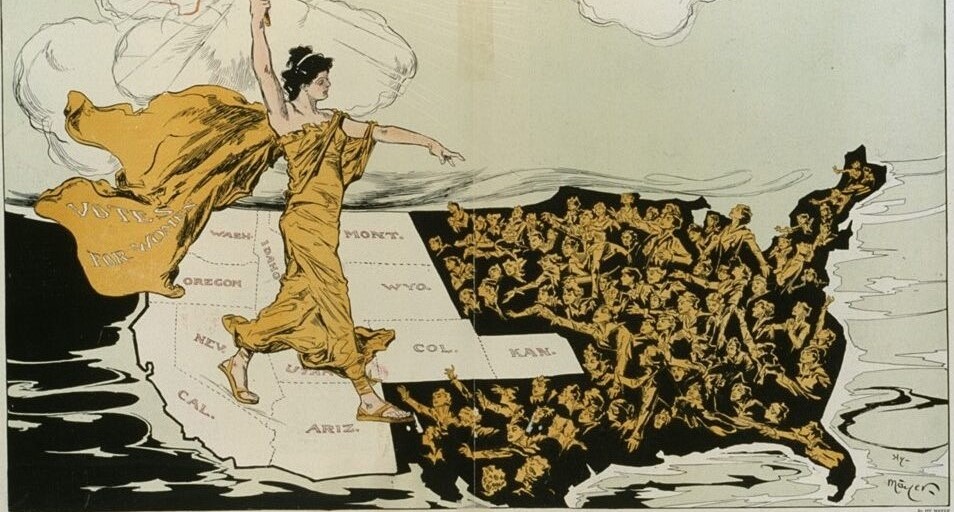

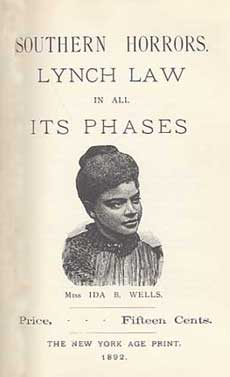

Booker T. Washington, the most prominent black leader, argued that African Americans should make themselves economically indispensable to southern whites, cooperate with whites, and accommodate themselves to white supremacy. But other figures adopted a more activist stance, such as the anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells, and W.E.B. DuBois, a founder of the NAACP, who demanded an end to caste distinctions based on race.

A tight labor market during World War I triggered the “Great Migration” of African Americans to the North, which continued into the 1920s. But the movement of blacks out of the South was met by racial violence in Chicago, East St. Louis, Houston, Tulsa, and other cities.

The Great Migration was accompanied by new efforts at black political and economic organization and cultural expression, including Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, which emphasized racial pride, economic self-help, and pan-Africanism, the political unity of all people of African descent, and the Harlem Renaissance, a literary and artistic movement.

The State of African Americans in the South

In 1900, the plight of African Americans in the South was bleak. The average life expectancy of an African American was thirty-three years—a dozen years less than that of a white American and about the same as a peasant in early nineteenth century India.

Thirty-five years after the abolition of slavery, the overwhelming majority of African Americans toiled in agriculture on land that they did not own. Nine out of ten African Americans lived in the South (almost the same proportion as in 1860), and three out of four were tenant farmers or sharecroppers.

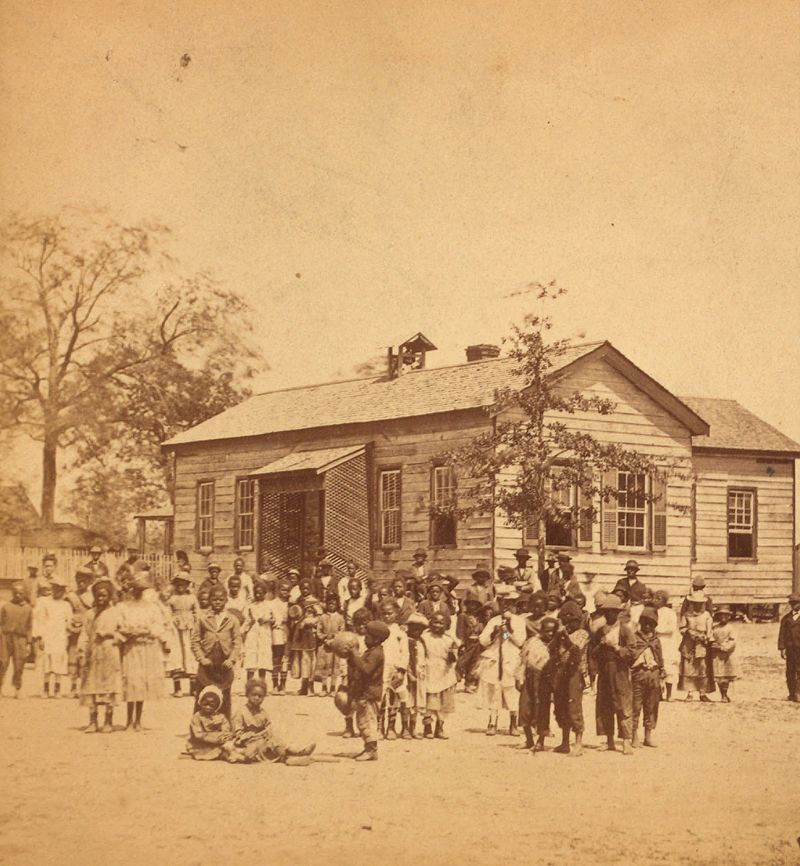

At the beginning of the twentieth century, some 44.5 percent of all African American adults were illiterate. In 1915, South Carolina spent one-twelfth as much on the education of a black child as on a white child. In 1916, only nineteen black youths were enrolled in public high schools in North Carolina and 310 were enrolled in Georgia.

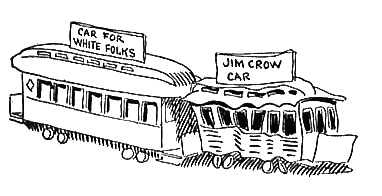

Increasingly, African Americans in the South were subject to a degrading system of social segregation and deprived of the right to vote and other prerogatives of citizenship. This system of racial discrimination based on law and custom was called “Jim Crow,” after a mid-nineteenth century black-faced minstrel act. Beginning with Mississippi in 1890, every Southern state, except Kentucky and Tennessee, had disenfranchised the vast majority of its African American population by 1907 through the use of literacy tests and poll taxes.

Lynching

A crowd of nearly 2,000 people gathered in Georgia in 1899 to witness the lynching of Sam Holt, an African American farm laborer charged with killing his white employer. A newspaper described the scene:

Sam Holt…was burned at the stake in a public road…. Before the torch was applied to the pyre, the Negro was deprived of his ears, fingers, and other portions of his body…. Before the body was cool, it was cut to pieces, the bones were crushed into small bits, and even the tree upon which the wretch met his fate were torn up and disposed of as souvenirs. The Negro’s heart was cut in small pieces, as was also his liver. Those unable to obtain the ghastly relics directly paid more fortunate possessors extravagant sums for them. Small pieces of bone went for 25 cents and a bit of liver, crisply cooked, for 10 cents.

From 1889 to 1918, more than 2,400 African Americans were hanged or burned at the stake. Many lynching victims were accused of little more than making “boastful remarks,” “insulting a white man,” or seeking employment “out of place.”

Before he was hanged in Fayette, Missouri, in 1899, Frank Embree was severely whipped across his legs and back and chest. Lee Hall was shot, then hanged, and his ears were cut off. Bennie Simmon was hanged, then burned alive, and shot to pieces. Laura Nelson was raped, then hanged from a bridge.

They were hanged from trees, bridges, and telephone poles. Victims were often tortured and mutilated before death: burned alive, castrated, and dismembered. Their teeth, fingers, ashes, clothes, and sexual organs were sold as keepsakes.

Lynching continues to be used as a stinging metaphor for injustice. At his confirmation hearings for the U.S. Supreme Court, Clarence Thomas silenced Senate critics when he accused them of leading a “high-tech lynching.”

Lynching was community sanctioned. Lynchings were frequently publicized well in advance, and people dressed up and traveled long distances for the occasion. The January 26, 1921, issue of The Memphis Press contained the headline: “May Lynch 3 to 6 Negroes This Evening.” Clergymen and business leaders often participated in lynchings. Few of the people who committed lynchings were ever punished. What makes the lynchings all the more chilling is the carnival atmosphere and aura of self-righteousness that surrounded the grizzly events.

Railroads sometimes ran special excursion trains to allow spectators to watch lynchings. Lynch mobs could swell to 15,000 people. Tickets were sold to lynchings. The mood of the white mobs was exuberant—men cheering, women preening, and children frolicking around the corpse.

Photographers recorded the scenes and sold photographic postcards of lynchings, until the Postmaster General prohibited such mail in 1908. People sent the cards with inscriptions like: “You missed a good time” or “This is the barbeque we had last night.”

Lynching received its name from Judge Charles Lynch, a Virginia farmer who punished outlaws and Tories with “rough” justice during the American Revolution. Before the 1880s, most lynchings took place in the West. But during that decade the South’s share of lynchings rose from twenty percent to nearly ninety percent. A total of 744 blacks were lynched during the 1890s. The last officially recorded lynching in the United States occurred in 1968. However, many consider the 1998 death of James Byrd in Jasper, Texas, at the hands of three whites who hauled him behind their pick-up truck with a chain, a later instance.

It seems likely that the soaring number of lynchings was related to the collapse of the South’s cotton economy. Lynchings were most common in regions with highly transient populations, scattered farms, few towns, and weak law enforcement—settings that fueled insecurity and suspicion.

The Census Bureau estimates that 4,742 lynchings took place between 1882 and 1968. Between 1882 and 1930, some 2,828 people were lynched in the South, 585 in the West, and 260 in the Midwest. That means that between 1880 and 1930, a black Southerner died at the hands of a white mob more than twice a week. Most of the victims of lynching were African American males. However, some were female, and a small number were Italian, Chinese, or Jewish. Mobs lynched 447 non-blacks in the West, 181 non-African Americas in the Midwest, and 291 in the South. The hangings of white victims rarely included mutilation.

Apologists for lynching claimed that they were punishment for such crimes as murder and especially rape. But careful analysis has shown that a third of the victims were not even accused of rape or murder; in fact, many of the charges of rape were fabrications. Many victims had done nothing more than not step aside on a sidewalk or accidentally brush against a young girl. In many cases, a disagreement with a white storeowner or landowner triggered a lynching. In 1899, Sam Hose, a black farmer, killed a white man in an argument over a debt. He was summarily hanged and then burned. His charred knuckles were displayed in an Atlanta store window.

The journalist G.L. Godkin wrote in 1893: “Man is the one animal that is capable of getting enjoyment out of the torture and death of members of its own species. We venture to assert that seven-eighths of every lynching part is composed of pure, sporting mob, which goes…just as it goes to a cock-fight or prize-fight, for the gratification of the lowest and most degraded instincts of humanity.”

Opponents of lynching, like the African American journalist Ida B. Wells, sent detectives to investigate lynchings and published their reports.

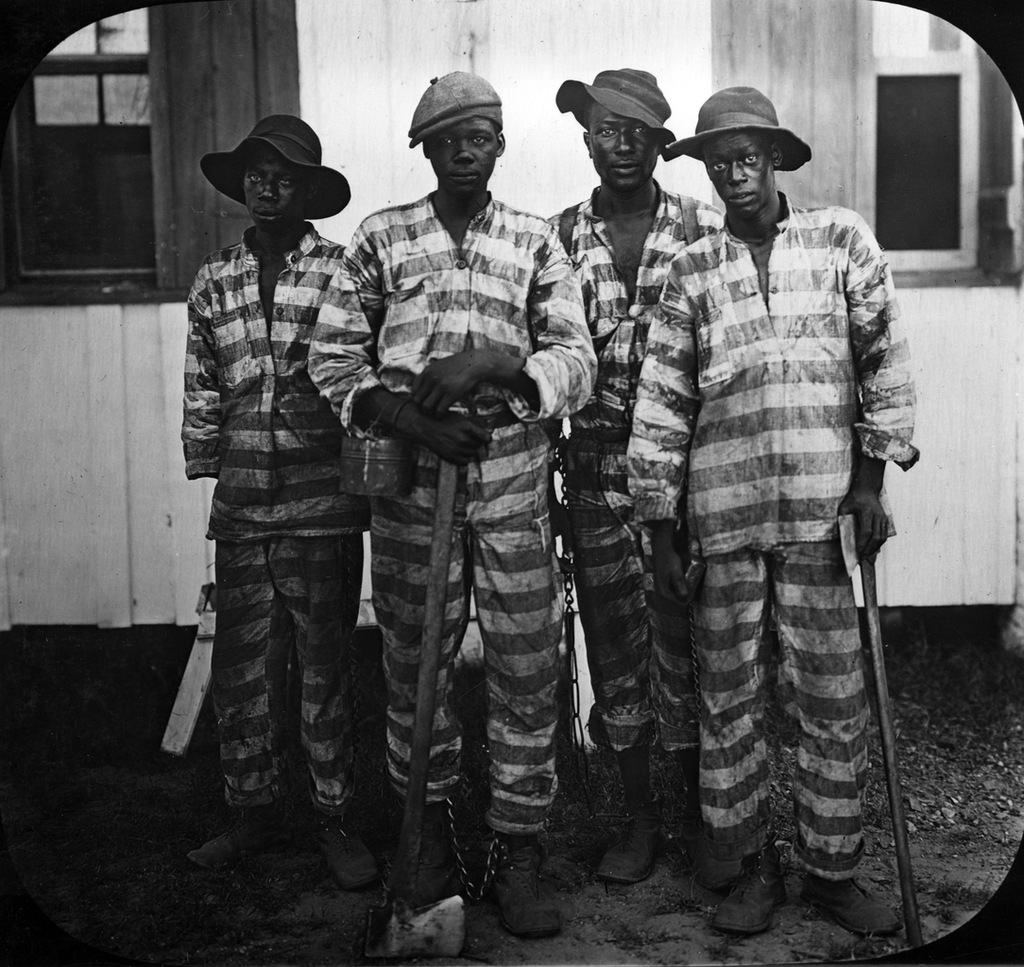

Convict Lease System

While most believe that the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, a loophole was opened that resulted in the widespread continuation of slavery in the Southern states of America—slavery as punishment for a crime. According to the Thirteenth Amendment, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, nor any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Convict leasing began in Alabama in 1846 and lasted until July 1, 1928, when Herbert Hoover was vying for the White House. In 1883, about ten percent of Alabama’s total revenue was derived from convict leasing. In 1898, nearly 73 percent of total revenue came from this same source. Death rates among leased convicts were approximately ten times higher than the death rates of prisoners in non-lease states. In 1873, for example, 25 percent of all black leased convicts died. Possibly, the greatest impetus to the continued use of convict labor in Alabama was the attempt to depress the union movement.

Convicts were leased to prominent and wealthy Georgian families who worked them on railroads and in coal mining. Arkansas actually paid companies to work their prisoners for much of the time the system was in place. No state official was empowered to oversee the plight of the prisoners, and businesses had complete autonomy in the disposition and working conditions of convict laborers. Mines and plantations that used convict laborers commonly had secret graveyards containing the bodies of prisoners who had been beaten and/or tortured to death. Convicts would be made to fight each other, sometimes to the death, for the amusement of the guards and wardens.

Unlike the other Southern states, only half of Texas inmates were black. Blacks were sent to sugar plantations.

The Southern states were generally broke and could not afford either the cost of building or maintaining prisons. The economic but morally weak and incorrect solution was to use convicts as a source of revenue, at least, to prevent them from draining the fragile financial positions of the states. The abolition of the system was also motivated mostly by economic realities. While reformers brought the shocking truths and abuses of this notorious system before the eyes of the world, the real truth was far different. In every state, the evils of convict labor and abuses were in newspapers and journals within two years of implementation and were generally repeated during every election cycle.

The convict leasing system was not abolished but merely transformed. Prisoners, who labored for private companies and businesses increasing their profits, now labored for the public sector. The chain gang replaced plantation labor.

Segregation and Disfranchisement

During the 1880s, many African Americans continued to vote in the South. The physical segregation of the races, which a later generation took for granted was not yet a codified system. But beginning in Florida in 1887, Southern states moved to separate the races on railroads. After 1900, segregation spread to nearly every facet of Southern life. In 1890, Mississippi adopted several devices—including the poll tax and the literacy test—to disfranchise African Americans. All other Southern states followed suit by 1910.

Why race relations worsened in the late 1880s and 1890s is a hotly contested question.

In part, it reflected the collapse of the cotton economy, which led many whites to search for scapegoats.

Mounting discrimination was also related to a fear among many Southern whites that a new generation of African Americans, which had been born after the Civil War and had not been subjected to slavery, would not defer to white authority.

In addition, the extreme violence was a reaction against the increasing economic independence of Southern blacks. From 1880 to 1900, black farm ownership increased from 19.6 to 25.4 percent, while sharecropping declined from 54.4. to 37.9 percent.

Jim Crow and the Courts

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the court severely limited federal power to fight lynchings and private discrimination. When the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted in 1868, it was expected that the Supreme Court would protect the rights of African Americans. But in the thirty years after the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, the Supreme Court restricted its scope. Eight years after the Civil War, the Supreme Court ruled in the Slaughter-House Cases that the Fourteenth Amendment’s prohibition against states restricting the privileges or immunities of American citizens was not intended to protect citizens of a state against the legislative power of their state. The court made this 1873 ruling even though the Fourteenth Amendment states in its first paragraph:

No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The Supreme Court decision in the Slaughter-House Cases reduced the “privileges and immunity” clause to a dead-letter. A five to four majority held that the clause only protected the rights of national citizenship and placed no new obligations on the states. This ruling left African American residents of the South powerless against discriminatory actions by state legislatures.

In the Civil Rights Case (1883), involving an inn in Jefferson, Missouri, which barred blacks, the court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment did not give Congress the power to ban private discrimination in public accommodations.

In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the court said that the Fourteenth Amendment “could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.” It would not be until 1954 that a unanimous Supreme Court would rule that legal segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause.

Plessy v. Ferguson

In 1890, Louisiana passed a law prohibiting people of different races from traveling together on trains. This law was one of many forms of segregation, formal and informal, that came to be known as Jim Crow (named after a minstrel song). A group of African American educators, lawyers, journalists, and civic leaders in New Orleans decided to test the law in court. At the time, New Orleans had the country’s largest African American population. “This act,” black leaders declared, “will be a license to the evilly disposed…to insult, humiliate and maltreat…those who have a dark skin.”

Homer Plessy, a shoemaker whose great-grandmother was black, challenged the law by sitting in a car reserved for white passengers. Despite the fact that he was seven-eighths white, he was arrested and convicted. Plessy’s attorney argued that the state law violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws.

The Supreme Court ruled in Louisiana’s favor in 1896. Segregation statutes were constitutional, the court said, as long as equal provisions were made for both races. The court’s majority declared:

We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.

The court’s majority distinguished between legal or political equality and social equality. According to the majority opinion, the Fourteenth Amendment only protected legal and political equality.

Justice John Marshall Harlan, the son of a Kentucky slave owner and himself a former Confederate officer, issued the lone dissent, saying it was wrong to separate citizens on the basis of race. “Our Constitution is color blind,” he wrote, “…all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful.” “What can more certainly arouse race hate, what more certainly create and perpetuate a feeling of distrust between these races,” he asked, “than state enactments which…proceed on the ground that colored citizens are so inferior…that they cannot be allowed to sit in public coaches occupied by white citizens?”

Harlan, who had a black half-brother sixteen years his senior, warned that the Plessy decision “will in time prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case.” Harlan’s half-brother, Robert Harlan, had purchased his freedom for $500 and gone on to become Ohio’s most prominent black Republican.

In the Plessy decision, the court gave its sanction to the “separate but equal doctrine” and gave states permission to legally separate blacks and whites at everything from drinking fountains to schools. Plessy v. Ferguson remained in effect until it was reversed in 1954 by the court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision to integrate public schools.

The implications of the Plessy decision for education became apparent three years later. In 1897, the Richmond County, Georgia, school board closed the only African American high school in Georgia, even though state law required that school boards “provide of the same facilities for each race, including schoolhouses and all other matters appertaining to education.” At that time, the school board provided two high schools for white children. It also provided sufficient funds to educate all white children in the county, while it provided funding for only half of school-aged African American children.

The Supreme Court upheld the county’s decision. In the case of Cumming v. School Board of Richmond County, Georgia (1899), it ruled that African Americans not only had to show that a law or practice discriminated against them, but that it was adopted because of “racial hostility.”

The issues raised in the Plessy case are at the heart of a debate about race in America today: Whether race may be taken into account in hiring and promoting in the workplace, admission to schools, and the makeup of legislative districts. Today, it is opponents of affirmative action who quote Justice Harlan, arguing that race should not be used to remedy the effects of past discrimination.

Segregation

In Alabama, hospitals were segregated, as were homes for the mentally handicapped, the elderly, and the blind and the deaf. In Florida, a law ordered that textbooks used for black and white children be kept separate, even when they were in storage. In Louisiana, a law regulating circuses and sideshows required separate entrances, exits, and ticket windows, and required that they be at least twenty-five feet apart.

In South Carolina, a code required that black and white workers in textile factories labor in different rooms, using different water fountains and toilets as well as different stairways and pay windows.

In Atlanta, an ordinance banned amateur baseball games within two blocks of each other if the players were of different races. In New Orleans, ferries, public libraries, and even brothels were segregated. For a time, public education for African American children was eliminated past the fifth grade. On streetcars, there was a movable screen that black riders had to sit behind.

Woodrow Wilson became the first Southern president since before the Civil War. He brought segregation to the federal bureaucracy, setting up all-black divisions within agencies.

Disfranchisement

Within five years of the Plessy decision, most Southern states had circumvented the Fifteenth Amendment and deprived African Americans of the vote by using such devices as literacy tests, property requirements, poll taxes, and white-only primaries. In 1896, in Louisiana there were 130,334 black registered voters. In 1904, there were only 1,342. Proponents of disfranchisement justified it as a way to end electoral fraud and violence and to ensure that only an educated citizenry would take part in elections.

The poll tax was typically a one or two-dollar tax, which was the equivalent of several days’ pay. By 1910, all of the Southern states had adopted a poll tax. Turnout dropped dramatically, and in most areas, all-white primaries determined the election of government officials. As late as 1935, the Supreme Court allowed the Texas Democratic Party to exclude black voters from the Democratic primary, even though a primary victory was tantamount to election.

It should be noted that after 1900, Northern states also imposed literacy tests and registration requirements to “purify” their own electorate and to reduce the influence of “ignorant” or boss-controlled votes in urban centers.

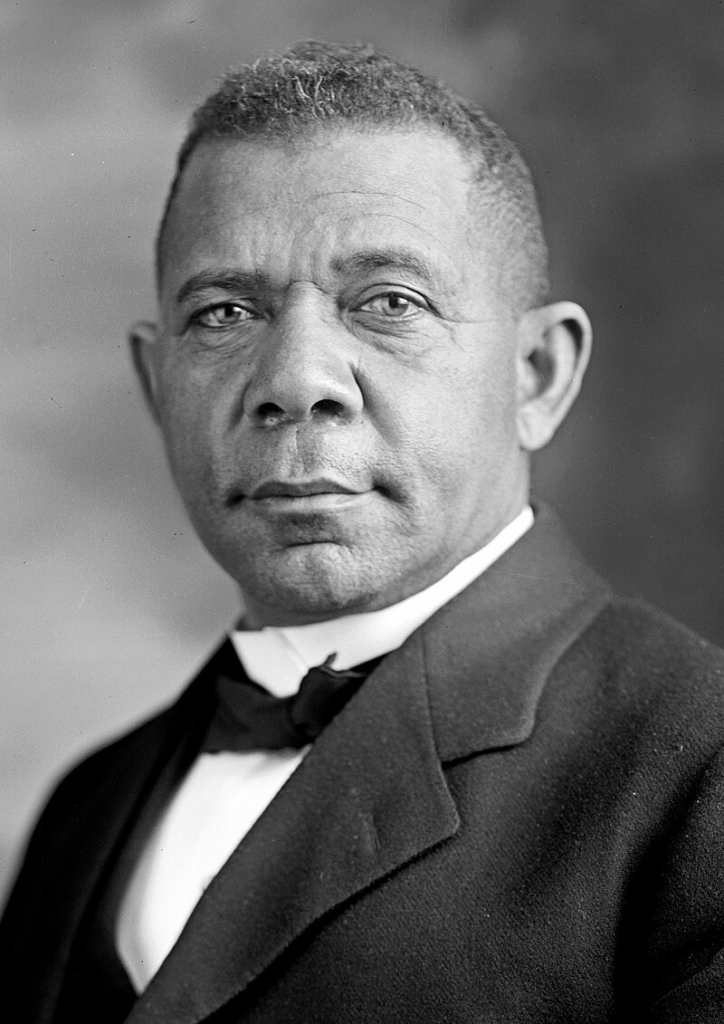

Booker T. Washington and the Politics of Accommodation

As the plight of African Americans in the South was beginning to worsen, Booker T. Washington, principal of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, was invited to speak before a bi-racial audience at the opening of the 1895 Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition—a celebration of the “new” industrializing South. A former slave who had toiled in West Virginia’s salt mines and earned a degree from Hampton Institute, Washington was the first African American to ever address such a large group of Southern whites. Frederick Douglass had died several months earlier, and Washington would immediately take his place as the spokesperson for his people.

In his ten-minute oration, which is often termed the “Atlanta Compromise,” Washington called for patience, accommodation, and self-help. He played down political rights and emphasized vocational education as the best way for African Americans to advance. “In all things that are purely social,” Washington said, “we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” African Americans, he recommended, should accommodate themselves to racial prejudice and concentrate on economic self-improvement. To his critics, this was capitulation to segregation.

From 1895 to 1915, Washington was viewed as African Americans’ leading spokesperson. His autobiography, Up from Slavery, became a best seller. He was the first African American to dine at the White House, and he had an audience with Britain’s Queen Victoria.

Yet, he also received bitter opposition from critics led by W.E.B. DuBois, the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard and a co-founder of the National Association of Colored People. DuBois, born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, believed that the only way to defeat segregation was through protest and agitation.

Washington was harshly criticized for failing to ask President Theodore Roosevelt to suppress a race riot in Atlanta (in which ten blacks died) or to condemn the President’s dismissal of three companies of black soldiers after a riot in Brownsville, Texas. What Washington’s critics did not know was that he sometimes worked quietly behind the scenes. He secretly bankrolled legal challenges to disfranchisement and segregation on railroads.

At his death, a commentary in the Nation criticized Washington for failing to demand full civil and political equality for African Americans:

He had failed to speak out on the things which the intellectual men of the race deemed of far greater moment than bricks and mortar, industrial education, or business leagues—the matter of their social and political liberties.