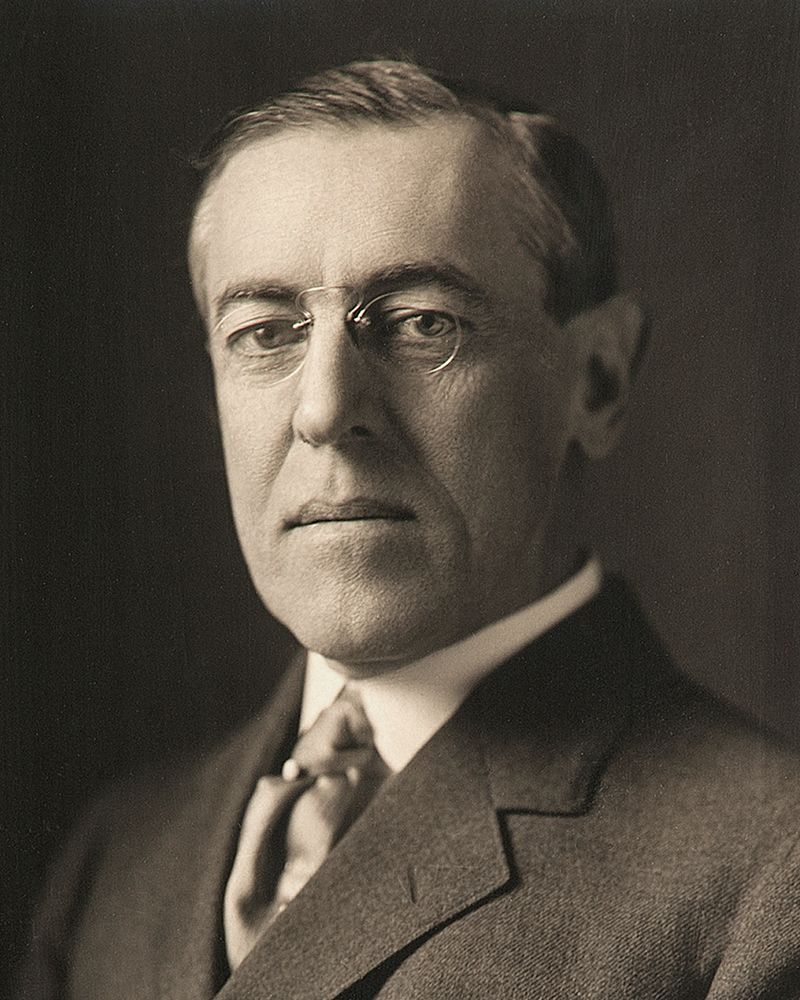

Woodrow Wilson

Wilson

The split in the Republican ranks in 1912 enabled Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency. Despite receiving only 42 percent of the popular vote, Wilson steered through Congress the creation of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Trade Commission, tariff reduction, anti-trust legislation, and a graduated income tax.

Wilson began as something of an isolationist in foreign policy. He apologized to Colombia for the U.S. role in Panama’s independence, and he appointed the pacifistic William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State. But he would later vow to teach Latin Americans lessons in democracy.

Only a week after taking office in 1913, Wilson called upon Mexico’s President, Victoriano Huerta, who had seized power after the constitutional president was murdered, to step aside when elections were held. When Huerta refused, Wilson used minor incidents—including the arrest of some American sailors in Tampico and the arrival of a German merchant ship carrying supplies for Huerta—as a pretext for occupying the Mexico port of Veracruz. Within weeks, Huerta was forced to leave his country.

During the conflict, the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa had made a number of raids into U.S. territory near the Mexican border. Wilson responded by ordering Gen. John J. (Black Jack) Pershing to cross into Mexico.

As president, Wilson also sent American troops to occupy Haiti in 1915 and the Dominican Republic in 1916. A year later, the United States bought the Virgin Islands, thereby gaining control of every major Caribbean island except British Jamaica. He engaged in more military interventions abroad than any other American president.

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was born in Virginia but grew up in Augusta, Georgia, where his father was an official of the Southern Presbyterian church. After briefly practicing as a lawyer (he only had two clients, one of whom was his mother), he attended graduate school at Johns Hopkins and taught history and political science at Bryn Mawr, Wesleyan, and Princeton—his alma mater. He wrote several highly acclaimed books, including Congressional Government, which decried the weakening of presidential authority in the United States, and The State, a call for increased government activism.

As Princeton’s president, he developed a reputation as a reformer for trying to eliminate the school’s elitist system of eating clubs. Professional politicians in New Jersey, wrongly thinking that they could manipulate the politically inexperienced Wilson, helped make him the state’s governor, and then, arranged his nomination as president in 1912. The nomination was a way to block another bid by William Jennings Bryan, whose prairie populism had been rejected three times by voters. Before he launched his campaign, Wilson described himself with these words:

I am a vague, conjectural personality, more made up of opinions and academic prepossessions than of human traits and red corpuscles. We shall see what will happen!

With the Republican vote split between Taft and Roosevelt, Wilson became the first Southerner to be elected president since the Civil War. He carried 40 states, but only 42 percent of the vote. After his election, the moralistic, self-righteous Wilson told the chairman of the Democratic Party: “Remember that God ordained that I should be the next president of the United States.” Wilson later said that the United States had been created by God “to show the way to the nations of the world how they shall walk in the paths of liberty.”

During his first term, he initiated a long list of major domestic reforms. These included:

- The Underwood Simmons Tariff (1913), which substantially lowered duties on imports for the first time since the Civil War and enacted a graduated income tax.

- The Federal Reserve Act (1913), which established a Federal Reserve Board and 12 regional Federal Reserve banks to supervise the banking system, setting interest rates on loans to private banks and controlling the supply of money in circulation.

- The Federal Trade Commission Act (1914), which established the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The FTC sought to preserve competition by preventing businesses from engaging in unfair business practices.

- Clayton Act Anti-Trust Act (1914), which limited the ownership of stock in one corporation by another, implemented non-competitive pricing policies, and forbade interlocking directorship for certain banking and business corporations. It also recognized the right of labor to strike and picket and barred the use of anti-trust statutes against labor unions.

Unlike Roosevelt, who believed that big business could be successfully regulated by government, Woodrow Wilson believed that the federal government should break up big businesses in order to restore as much competition as possible. Other social legislation enacted during Wilson’s first term included:

- The Seaman Act (1915), which set minimum standards for the treatment of merchant sailors.

- The Adamson Act (1916), which established an eight-hour workday for railroad workers.

- The Workingmen’s Compensation Act (1916), which provided financial assistance to federal employees injured on the job.

- The Child Labor Act (1916), which forbade the interstate sale of goods produced by child labor.

- The Farm Loan Act (1916), which made it easier for farmers to get loans.

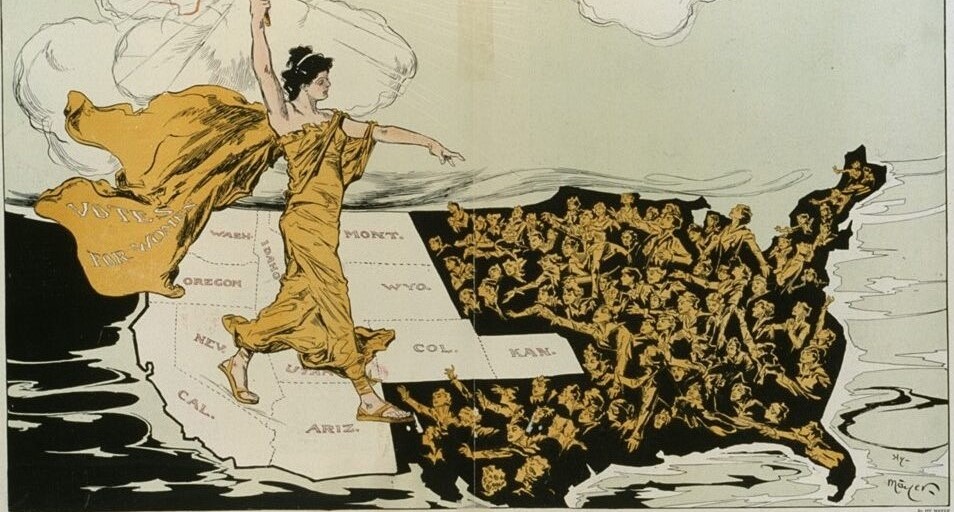

Following Wilson’s election in 1912, four constitutional amendments were ratified:

- Sixteenth Amendment (1913) gave Congress the power to impose an income tax.

- Seventeenth Amendment (1913) required the direct election of senators.

- Eighteenth Amendment (1919) banned the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages.

- Nineteenth Amendment (1920) gave women the right to vote.

Wilson’s second term was dominated by American involvement in World War I. At the end of September 1919, Wilson suffered a mild stroke. Then in early October, he had a major stroke that almost totally incapacitated him.

More than most presidents, Wilson’s historical reputation had swung up and down. During World War I, he was regarded by many Europeans as a latter-day Prince of Peace, who offered a vision of a new world that would promote peace and national self-determination. During the 1920s, he was viewed as a priggish and an anti-business president, an impractical visionary and fuzzy idealist who embroiled the United States in a needless war. During the 1940s, in sharp contrast, he was depicted in the Hollywood film, Wilson (1944), as an idealistic leader struggling to create a new world order based on international law. Today, Wilson is criticized on the left for his racial bias and by the right for his concentration of power in Washington. Staunch nationalists criticize Wilson’s commitment to collective security in which the United States would work hand-in-hand with other nations to promote world order. Meanwhile, many civil libertarians condemn Wilson’s administration for unprecedented violations of civil liberties.

Yet for all of the criticism that Wilson currently receives, succeeding presidents have, for the most part, followed his lead. He, like Theodore Roosevelt, was an activist president who viewed presidential leadership as essential to national progress.

Soaring words—like Abraham Lincoln’s, John F. Kennedy’s, and Martin Luther King’s—carry enormous power. They can inspire, enthrall, and drive public opinion.

Woodrow Wilson was a gifted phrasemaker, indeed, one of the most eloquent Presidents. Phrases like “The world must be made safe for democracy” and “universal self-determination” had enormous public consequences. His vision of an activist President and liberal internationalism continues to shape American foreign policy more than a century later. Today, his name is synonymous with the advancement of liberal democracy, national self-determination, and collective security as a way to prevent future wars.

Income Tax

The federal income tax is a surprisingly recent innovation. The modern progressive income tax was only introduced in 1913 as a result of the 16th Amendment to the Constitution.

Prior to the introduction of an income tax, the United States relied largely on revenues from tariffs and excise taxes. Indeed, as a result of revenue primarily generated by tariffs, the federal government ran surpluses from 1866 to 1893.

Republicans defended protective tariffs as a positive good. They claimed that a high tariff encouraged industrialization and urbanization, generated high wages and profits, and created a rich home market for farmers and manufacturers. Beginning in 1887, the Democrats, led by Grover Cleveland, argued that the tariff was a tax on consumers for the benefit of rich industrialists. Indeed, the tariff probably added ten percent or more to the cost of living for working-class Americans. Democrats claimed that the tariff raised prices, encouraged foreign countries to retaliate against American farm exports, and encouraged the growth of economic trusts. The tariff’s major beneficiaries were the producers of raw material, especially sugar, wool, hides, and timber.

By the end of the 1890s, revenue from the tariff was declining (since the United States was mainly importing raw materials), as was revenue from federal land sales. Meanwhile, government spending was increasing. By 1905, the expanding U.S. Navy was receiving twenty percent of the federal budget. At the same time, Congress expanded pensions for Civil War veterans.

In 1894, the government ran the first deficit since the Civil War and enacted a short-lived income tax, which was declared unconstitutional in 1895. The Supreme Court ruled that it violated a constitutional provision that taxes had to be apportioned among the states. The court reached this decision even though it had earlier upheld an income tax levied during the Civil War.

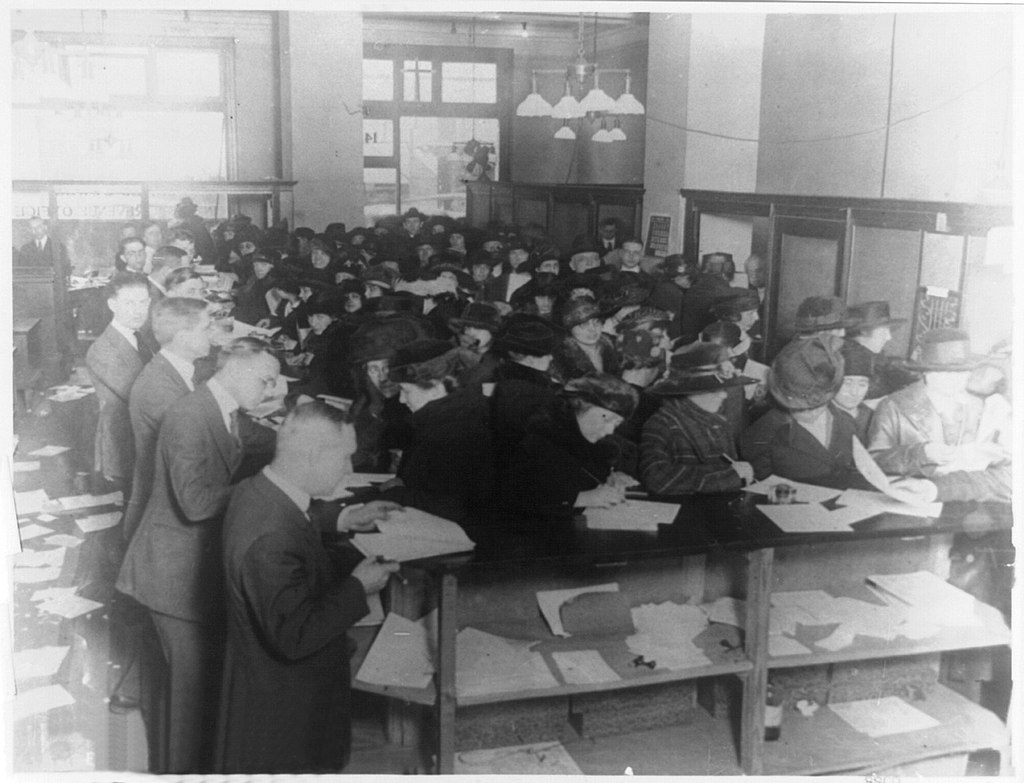

In April 1909, Southern and Western congressmen sponsored another income tax bill, hopeful that the Supreme Court with a new membership might approve it. Their opponents responded by sponsoring a constitutional amendment that would authorize an income tax, which they thought could not be ratified by three-fourths of the states. Congress approved the amendment overwhelmingly. The Senate vote was 77 to 0 votes; the House vote was 318 to 14 votes.

By the end of 1911, a total of 31 states (including New York and Maryland as well as many Southern and Western states) had approved the amendment—five short of the required number to pass. It appeared that the amendment had failed since no previous amendment had taken so long to be ratified.

But during the 1912 election, Democrat Woodrow Wilson and third-party candidate Theodore Roosevelt rekindled support for the amendment. The amendment eventually passed and went into effect when Wyoming became the 36th state to ratify in February 1913.

The new federal income tax was modest and affected only about one-half of one percent of the population. It taxed personal income at one percent and exempted married couples earning less than $4,001. A graduated surtax, beginning on incomes of $20,000, rose to six percent on incomes of more than $500,000. The $4,000 exemption expressed Congress’ conclusion that such a sum was necessary to “maintain an American family according to the American standard and send the children through college.” It was about six times the average male’s income. State officials were exempt from paying any taxes, as were federal judges and the president of the United States.

American involvement in World War I caused government expenditures to soar and international trade (and tariff revenues) to shrink. By 1919, the minimum taxable income had been reduced to $1,000, and the top tax rate was 77 percent. As late as 1939, only 3.9 million Americans had to file taxes. But just six years later, 42.6 million Americans filed. Tax withholding was introduced in congressional legislation in 1943. President Franklin Roosevelt vetoed this provision, but Congress overrode his veto.