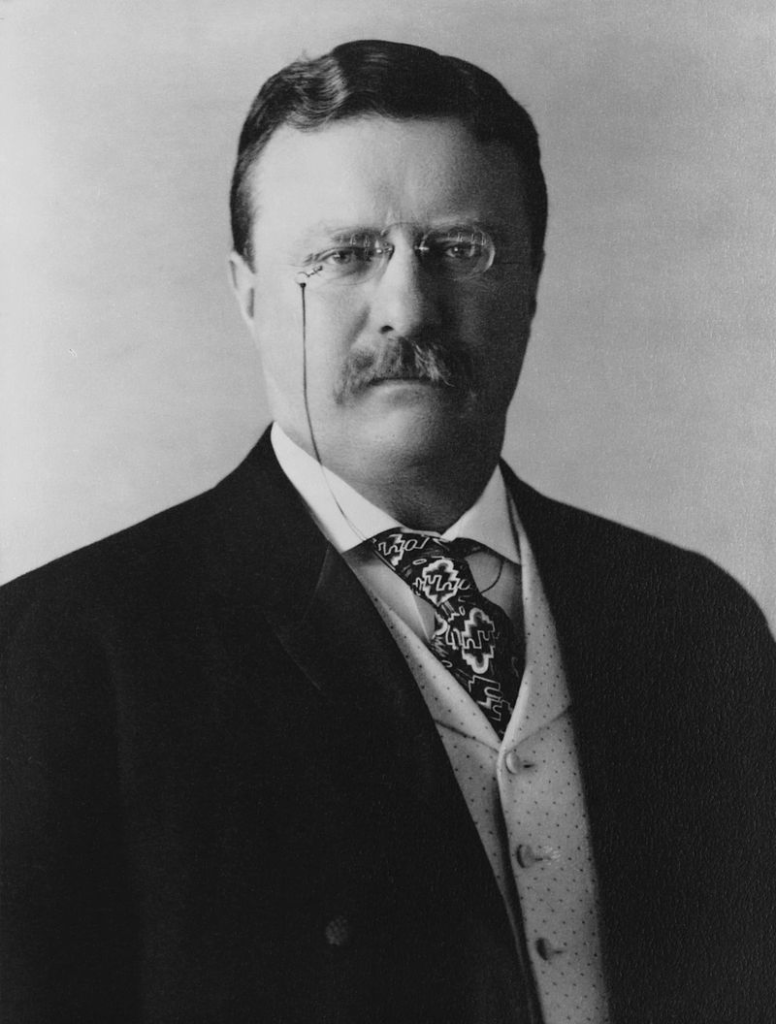

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

At the Republican convention in 1900, a senator warned his colleagues not to make Theodore Roosevelt their vice presidential nominee: “Don’t any of you realize that there’s only one life between this madman and the presidency?” As New York’s governor, Roosevelt had challenged banking and insurance interests; The state’s Republican Party boss Tom Platt wanted him out of state affairs and therefore supported him as a candidate for the vice presidency.

Born in New York City in 1858, Roosevelt was, in his own words, “nervous and timid” as a youth. He suffered headaches, fevers, and stomach pains. He was so frail and asthmatic that he could not blow out a bedside candle. So he hiked, swam, boxed, and lifted weights to build up his strength and stamina. In 1912, he would be shot in the chest by a deranged man, but proceeded to deliver an hour-long speech before having the bullet removed.

At the age of twenty-three, Roosevelt was elected to the New York state legislature. Then in 1884, his wife and his mother died on the same day. To distance himself from these tragedies, he retreated to a 25,000-acre ranch in North Dakota’s Badlands and became a cowboy. He wore spurs and carried a pearl-handled revolver from Tiffany, the New York jewelers.

Roosevelt returned to serve as a U.S. Civil Service commissioner. He also served as New York City’s crusading police commissioner, wearing disguises in order to root out corruption. He subsequently became Assistant Secretary of the Navy and governor of New York, before his election as vice president in 1900.

Lacking any military experience and wearing a uniform custom-tailored by Brooks Brothers, Roosevelt served as second-in-command of the Rough Riders, a volunteer cavalry unit that fought in Cuba during the Spanish American War. With William McKinley’s assassination, he became, at the age of 42, the youngest president in American history.

Even those who know nothing about his presidency instantly recognize his image carved on Mount Rushmore—his huge, toothy smile and his wire-rimmed glasses. As president, he made anti-trust, conservation of natural resources, and consumer protection national priorities. He forced coal operators to recognize the United Mine Workers.

Roosevelt’s life was filled with contradictions. He was a member of one of the country’s twenty richest families, yet he denounced business magnates as “malefactors of great wealth.” The first president born in a big city, he was a hunter as a well as a conservationist. He was a bellicose man who boxed in the White House. He was also the first American to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for brokering peace between Russia and Japan.

Incredibly active and energetic, Roosevelt was “a steam engine in trousers” who somehow found time to write three dozen books, on topics ranging from history to hunting and in languages ranging from Italian and Portuguese to Greek and Latin. He was the first celebrity president known simply by his initials. Said a British envoy, “You must always remember the president is about six.”

In office, Roosevelt greatly expanded the powers of the presidency. A bold and forceful leader, he viewed the White House as a “bully pulpit” from which he could preach his ideas about the need for an assertive government, the inevitability of bigness in business, and an active American presence in foreign policy. He broke up trusts that dominated the corporate world and regulated big business. He created the Departments of Commerce and Labor and the U.S. Forest Service. He supported a revolt in a province of Colombia that allowed the United States to build the Panama Canal. He sent a Great White Fleet on an around-the-world voyage to symbolize America’s rise to world power. He made a dramatic public statement about race when he invited Booker T. Washington to dine at the White House.

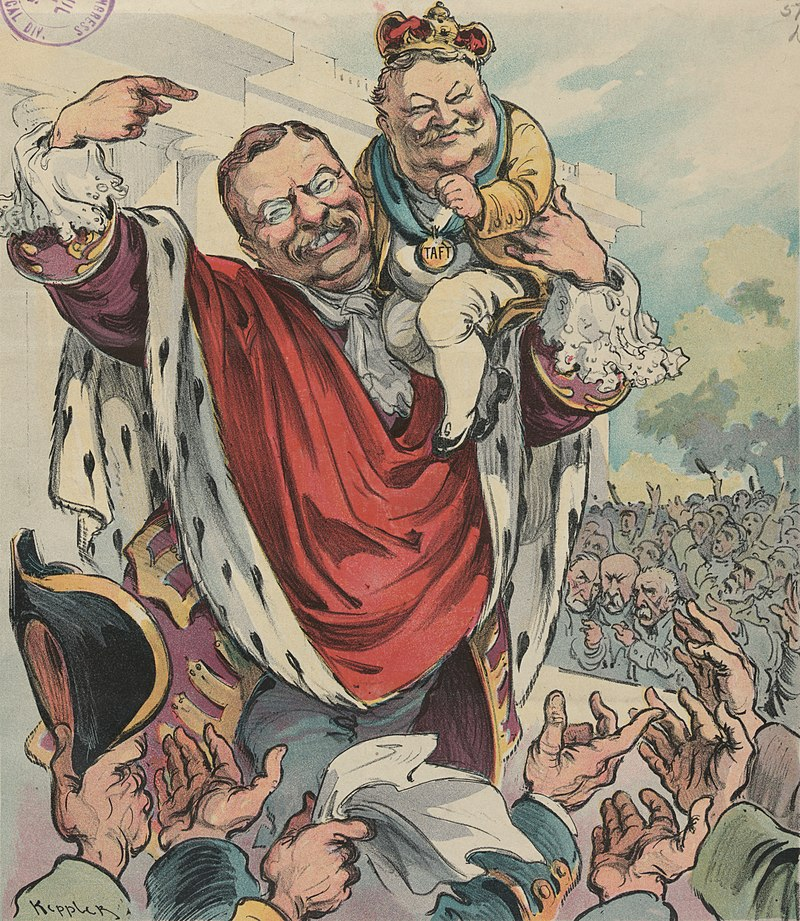

Roosevelt pushed legislation through Congress, authorizing and establishing the authority of the Interstate Commerce Commission to set railroad rates. In 1904, he won reelection by the largest popular majority up to that time. But on election night, he announced that he would not seek reelection in 1908—a statement that undercut his influence during his second term. In 1909, he retired to hunt big game in Africa, and passed the presidency to his hand-picked successor, William Howard Taft.

Apart from his philosophy of an active, interventionist government, Roosevelt’s most lasting legacy is that he became the model for a new kind of president: a charismatic, hyper kinetic, heroic leader, who sought to improve every aspect of society. He made the presidency as large as the problems posed by industrialization and urbanization.

Anti-Trust

One of the most significant issues Roosevelt confronted as president was how best to deal with the growth of corporate power. Between 1897 and 1904, a total of 4,227 firms merged to form 257 corporations. The largest merger combined nine steel companies to create U.S. Steel. By 1904, some 318 companies controlled nearly forty percent of the nation’s manufacturing output. A single firm produced over half the output in 78 industries.

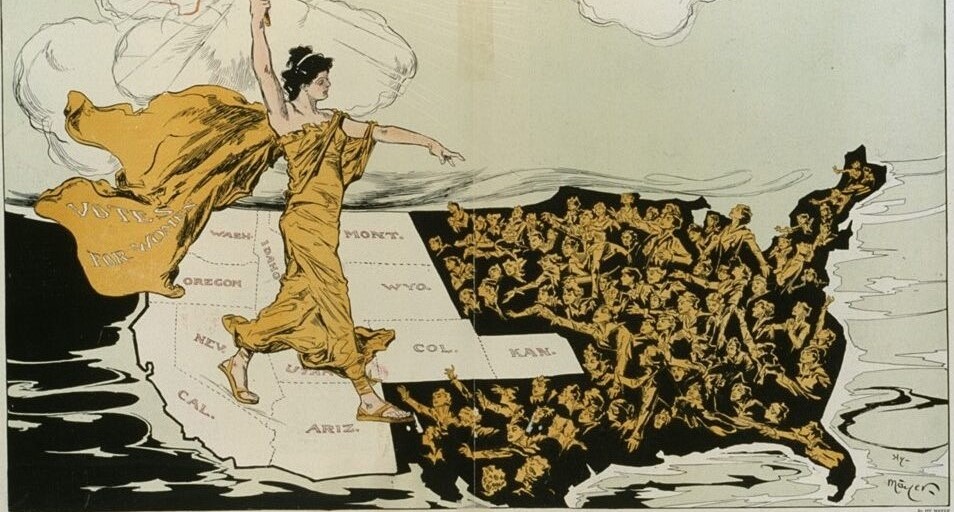

Many Progressives feared that concentrated, uncontrolled, corporate power threatened republican government. Public opinion feared that large corporations could impose monopolistic prices to cheat consumers and could squash small independent companies.

Roosevelt’s Justice Department launched 44 anti-trust suits, prosecuting railroad, beef, oil, and tobacco trusts. Henry Clay Frick, the steel baron complained, “We bought the son of a bitch and then he didn’t stay bought.” The most famous anti-trust suit, filed in 1906, involved John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. It took five years for Roosevelt to win his case in the Supreme Court. In the end, however, Standard Oil was broken into 34 separate companies.

Theodore Roosevelt did not oppose bigness in and of itself. He only opposed irresponsible corporate behavior. He distinguished between “good trusts” and bad trusts” and advocated regulating big corporations in the public interest by means of a government commission.

Government Regulation

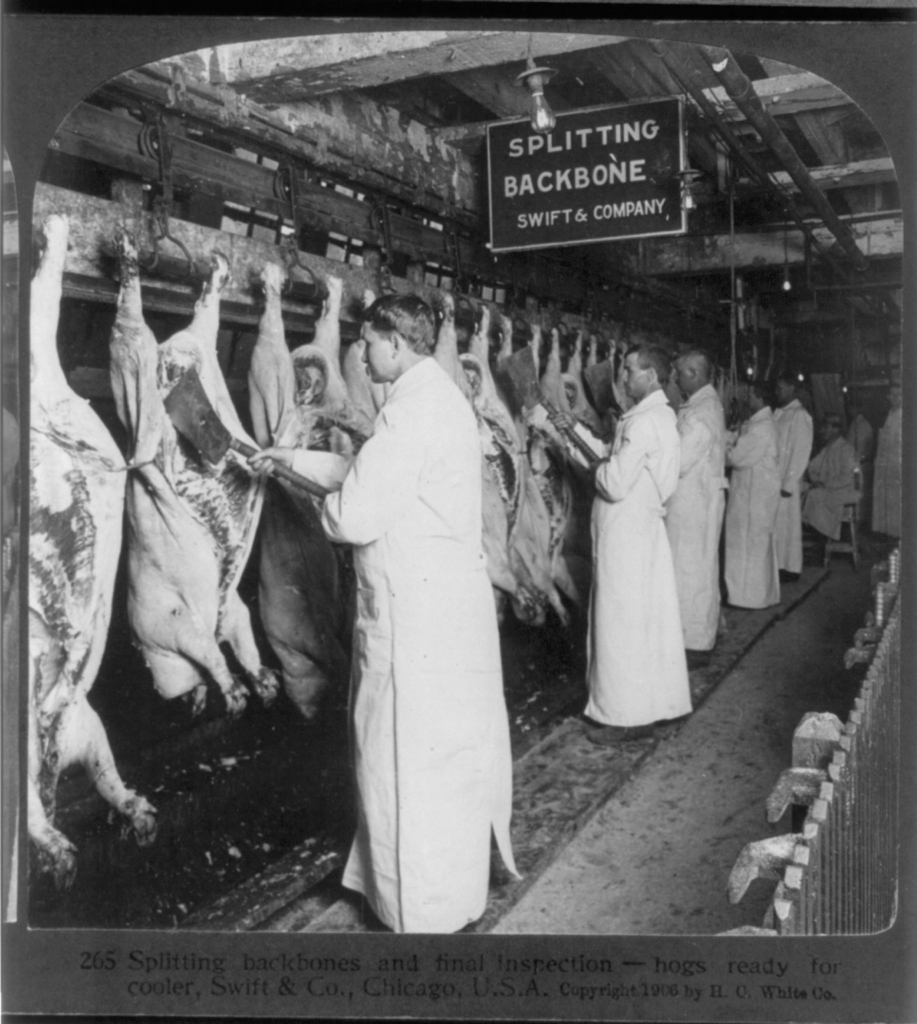

At the beginning of the twentieth century, milk distributors frequently adulterated milk by adding chalk or plaster to improve its color and molasses and water to cut costs. Meatpackers killed rats by putting poisoned pieces of bread on their floors. Sometimes, the poisoned rats made their way onto the production lines.

The publication of Upton Sinclair’s book, The Jungle, exposed unsanitary conditions in the meatpacking industry, generating widespread public support for federal inspection of meatpacking plants. The Department of Agriculture disclosed the dangers of chemical additives in canned foods. A muckraking journalist named Samuel Hopkins uncovered misleading and fraudulent claims in non-prescription drugs.

To deal with these problems the federal government enacted:

- The Meat Inspection Act (1906), mandating government enforcement of sanitary and health standards in meatpacking plants.

- The Pure Food and Drug Act (1906), prohibiting false advertising and harmful additives in food.

Progressives often portrayed their battles as simply the latest example of an older struggle between “the people” and business interests and proponents of democracy against the defenders of special privilege. In fact, this view is quite misleading. Corporate managers were often strong supporters of Progressive reform. During Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency, mining companies worked closely with the administration in order to try to rationalize the extraction of natural resources. Big meatpackers promoted the Meat Inspection Act of 1906 to prevent smaller packers from exporting bad meat and closing foreign markets to all American meat products.

Conservation

The United States was the first nation in the world to create wilderness parks. Theodore Roosevelt launched conservation as a national political movement. As president, he argued on behalf of conserving natural resources and preserving wild lands. He set aside the first national monuments and wildlife refuges. In 1906, he signed the Antiquities Act, which enabled a president to protect wild lands as national monuments. The Grand Canyon was among the places he protected under the act.

The youngest person to ever become president, Theodore Roosevelt as chief executive conserved millions of Western acres, swung his “big stick” at business trusts, advanced progressive agendas on race and labor relations, fostered a revolution in Panama (in order to build a canal), won the Nobel Peace Prize for mediating an end to the Russo-Japanese War, and pushed through the Pure Food and Drug Act.

An arch opponent of socialism, he played a pivotal role in ending the era of laissez-faire economics and fought for stronger government regulation of business. In direct opposition to Republican doctrine of his era and today, he favored a much stronger centralized government.

Roosevelt helped to transform the popular conception of the presidency. He used his “bully pulpit”—his position of authority—to shape the public agenda. In office, he greatly contributed to the growth of presidential power, decisively shifting the balance between the three branches of government.

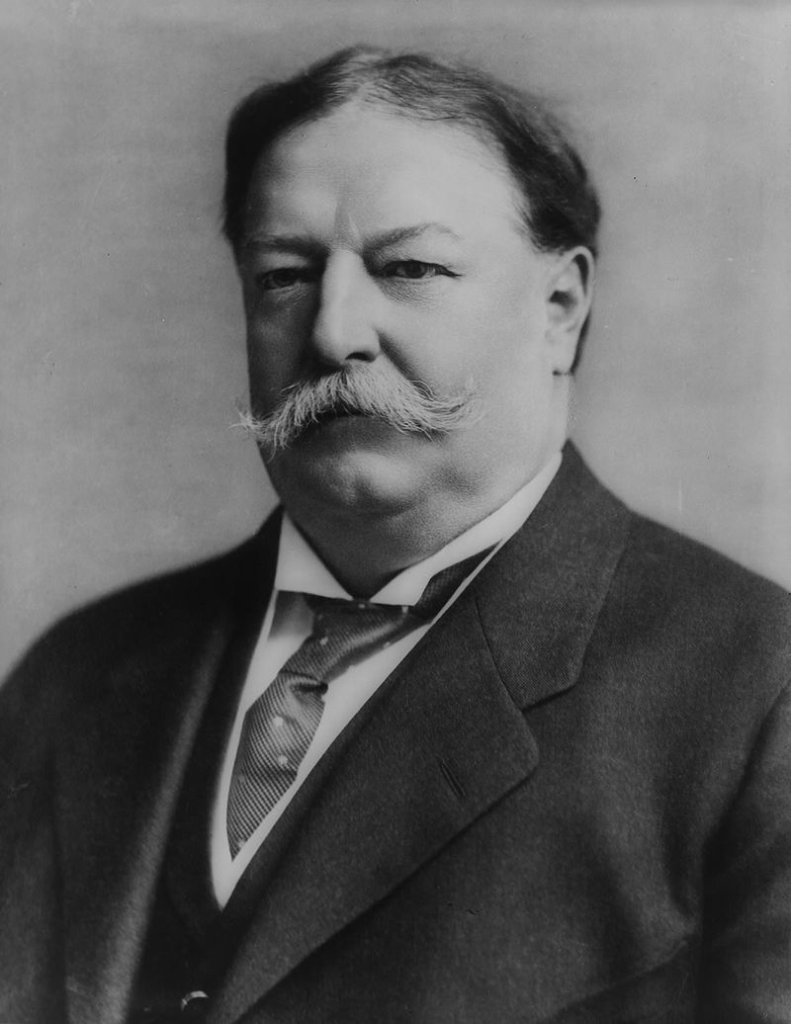

Taft

Today, William Howard Taft is better known for his weight than for his presidency. The most corpulent president, he was six-feet, two-inches tall and weighed 330 pounds. A special bathtub was installed in the White House large enough to accommodate four average sized adults. When he was governor of the Philippines, he sent a cable that referred to a horseback ride he had taken into the mountains. The reply: “Referring to your telegram—how is the horse?”

Taft had served as a federal judge and as the appointed governor of the Philippines before Roosevelt named him secretary of war. However, his talents as administrator served him poorly as a president. He was perceived, wrongly, as a tool of entrenched interests. In 1930, he was appointed chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

As president, Taft had very substantial Progressive accomplishments. He filed twice as many anti-trust suits as Roosevelt, expanded Roosevelt’s program of conserving public lands, created a Children’s Bureau within the Labor Department, and pushed through Congress the Mann-Elkins Act of 1910, which strengthened the federal government’s power to regulate the railroads. He also submitted a proposal for a tax on corporate income and called for a constitutional amendment to permit an income tax. The amendment was ratified in 1913 during the waning days of days of his administration.

Taft also fired Roosevelt’s trusted lieutenant, Gifford Pinchot, who had attacked his conservation policies. He supported the reelection of Joe Cannon, the Republican old guard speaker of the House, in return for conservative support on other issues. He tried to lower tariffs on foreign trade, only to have his proposal gutted by Congress. Said Roosevelt of his successor:

Taft, who is such an admirable fellow, has shown himself such an utterly commonplace leader, good-natured, feebly well-meaning, but with plenty of small motive; and totally unable to grasp or put into execution any great policy.

Disenchanted with Taft and missing the glory of the presidency, Roosevelt challenged his successor for the 1912 presidential nomination. “We stand at Armageddon,” said Roosevelt in 1912, “and we battle for the Lord.”

During the campaign, Roosevelt called the president a “fathead” and a “puzzlewit” who was “dumber than a guinea pig.” Roosevelt’s remarks deeply embittered Taft. “Even a cornered rat will fight,” he reported said to a journalist.

Roosevelt won most of the primaries, but lost a rules fight at the Republican convention, and won only a third of the delegates. Charging Taft with “hijacking” the nomination, Roosevelt launched a third party. As the Progressive Party candidate, Roosevelt received 27 percent of the vote—which today is still a record for a third-party presidential candidate. Taft only won 23 percent of the popular vote, partly due to his failure to publicize his progressive achievements.

It is not easy to follow a highly popular president. A third place finisher in the election of 1912, William Howard Taft—the only person to serve both as President and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court—resides in the shadows of both Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

Roosevelt’s hand-picked successor, Taft busted more trusts than TR did, advanced the cause of conservation, and strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission’s ability to regulate railroad rates. On his watch, Congress passed the Sixteenth and Seventeenth amendments, providing for a federal income tax and the direct election of senators.

Yet for all his achievements, Taft was in important ways a throwback to an earlier, more restrained conception of the office of the presidency. As a result, his reputation pales in comparison to Roosevelt and Wilson.