Progressivism in Government

Progressivism in Government

According to Croly, the challenge confronting early twentieth century America was to respond to the problems that had accompanied the transformation of American society from a rural, agricultural culture into an urban, industrial society. Filled with faith in the power of government, Progressives launched reform in the areas of public health, housing, urban planning and design, parks and recreation, workplace safety, workers’ compensation, pensions, insurance, poor relief, and health care.

Municipal Progressivism

Tom L. Johnson represented a model of Progressivism at the local level. He was a four-term mayor of Cleveland from 1901 to 1909. In office, he removed all the “Keep Off the Grass” signs from parks and embarked on an aggressive policy of municipal ownership of utilities. He fought the streetcar monopoly, reformed the police department, professionalized city services, and built sports fields and public bathhouses in poor sections of the city. He also coordinated the architecture and placement of public buildings downtown, set around a mall.

James Michael Curley, Boston’s mayor, represented the kind of leader that many Progressives opposed. The Boston Evening Transcript called Curley “as clear an embodiment of civic evil as ever paraded before the electorate.” Twice sent to prison for fraud, he acquired a 21-room mansion (which had gold-plated bathroom fixtures) paid for by kickbacks from contractors.

The son of an Irish washerwoman, Curley won office by speaking the language of class and ethnic resentment. But Curley also built new schools for the children of working-class Bostonians, tore down slum dwellings, established beaches and parks for the poor, and added an obstetrics wing to the city hospital. He also helped the poor in very direct ways. He provided bail money, funeral expenses, and temporary shelter for those made homeless by fire or eviction. When he died, a million people lined Boston’s streets to pay their last respects.

To weaken political machines, municipal Progressives sought to reduce the size of city councils and to eliminate the practice of electing officials by ward (or neighborhood). Instead, they proposed electing public officials on a city-wide (an at-large) basis. Candidates from poorer neighborhoods lacked funds to publicize their campaigns across an entire city. Urban Progressives also diminished the influence of machines by making municipal elections non-partisan, by prohibiting the use of party labels in local voting. A number of cities attempted to eliminate politics from city government by introducing city managers. Beginning with Staunton, Virginia, in 1908, a number of cities began to hire professional administrators to run city government.

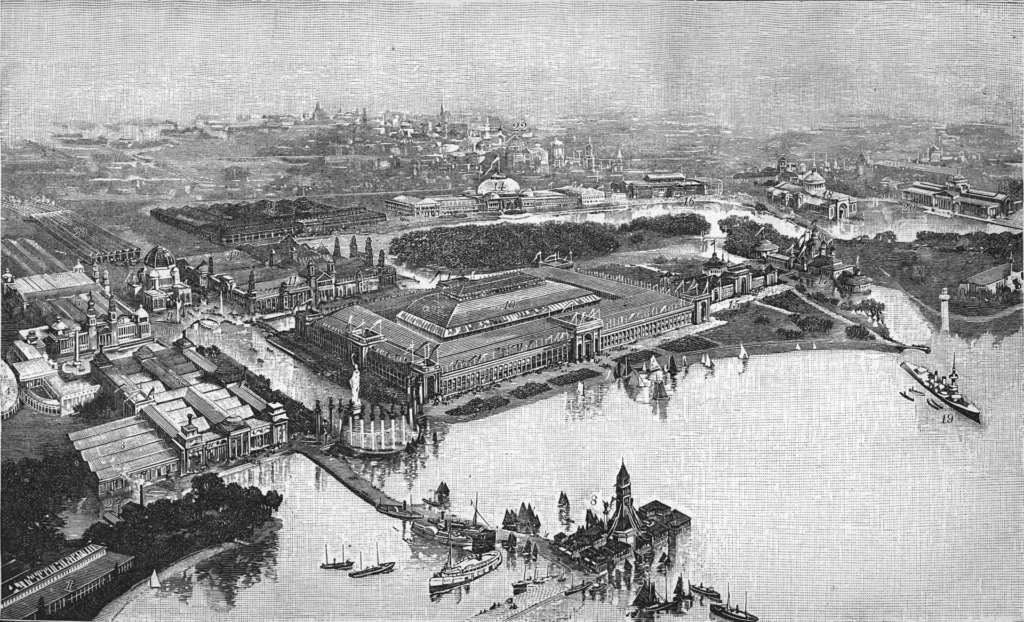

Many Progressives wanted to improve the quality of urban life. The World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893, marking the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage of discovery, was an inspiration to many urban reformers. As a symbol of its recovery from the disastrous Great Fire of 1871, Chicago erected a massive “White City” to hold the event. Chicago’s White City demonstrated the value of careful planning and beautification and provided the impetus for many Progressive efforts to introduce city planning, zoning regulations, housing reform, and slum clearance.

The most far-reaching progressive effort to transform the city was known as “municipal socialism.” Many cities established municipal waterworks, gasworks, and electricity and public transportation systems.

State Progressivism

During the Progressive era, the states were “laboratories for democracy,” where state governments experimented with a wide range of reforms to eliminate governmental corruption, abolish unsafe working conditions, make government more responsive to public needs, and protect working people.

The severe Depression beginning in 1893 had discouraged states from engaging in policy innovation. Government retrenchment was the watchword of many lawmakers in the 1890s. Most of the endeavors reformers undertook during these years were efforts to eliminate political bossism, corruption, and governmental waste. The Depression also encouraged the consolidation of corporations, a development that would make trusts a major issue after the turn of the century. The Spanish American War had also diverted attention from domestic matters.

During the early twentieth century, many states adopted reforms that had been enacted years earlier in Massachusetts, which, along with Rhode Island, had been the first state to have a majority of its population live in cities. Many of these reforms involved protections for working people, including:

- Compulsory school attendance laws, adopted in every state except Mississippi by 1916.

- Laws limiting work hours for women and children in 32 states, and minimum wages for women workers in eleven states.

- Workmen’s compensation, which provided compensation for workers injured on the job in 32 states.

Other laws established an eight-hour workday for state employees, authorized credit unions, created public utility commission, established state employee pensions, and instituted a host of health and safety regulations. Several states also passed laws prohibiting children from working at night.

To make the electoral process more democratic, all but three states adopted direct primaries by 1916, which allowed voters to choose among several candidates for a party’s nomination. To allow voters to express their dissatisfaction with elected officials, Progressives proposed the recall, which allowed voters to vote to remove them before the end of their term in office. To give voters a greater voice in law making, Progressives proposed the initiative and the referendum. The initiative allowed voters to propose a bill and legislation, and the referendum permitted them to vote directly on an issue. Oregon, South Dakota, and Utah were the first states to adopt the initiative and referendum.

Beginning in the 1880s, Britain, France, Germany, and Scandinavia adopted a series of social welfare programs—unemployment insurance, old-age pensions, and industrial accident and health insurance. During the Progressive era, many reformers borrowed these ideas and adapted them to meet American circumstances.

Perhaps the most dramatic American innovation was “widow’s pensions.” Adopted by most states, these programs provided widows with a monthly payment that allowed them to keep their children at home, rather than putting them in orphanages or up for adoption.

National Progressivism

On September 6, 1901, President William McKinley was shaking hands with a line of well-wishers at the Pan American Exposition held in Buffalo, New York. Fifty soldiers and secret service agents roamed the premises, scrutinizing the crowd. A 28-year-old ex-Cleveland factory worker and farm hand named Leon Czolgosz (pronounced Chol-gots) moved toward the president and drew a 32-caliber revolver from his pockets. He wrapped his left hand and the gun with a large handkerchief.

A secret service agent touched Czolgosz shoulder. “Hurt your hand?” the agent asked. Czolgosz nodded. “Maybe you better get to the first aid station.” Czolgosz replied: “After I meet the president. I’ve been waiting a long time.”

Czolgosz approached McKinley and said, “Excuse my left hand, Mr. President.” McKinley shook his hand and the farm hand moved on. After several more citizens extended their greetings, Czolgosz lunged toward the president. As a secret service agent tried to grab him, Czolgosz fire twice in rapid succession. One bullet was deflected by McKinley’s breastbone, but the other ripped through his stomach and lodged in his back. “I done my duty!” Czolgosz cried out. The president died eight days later.

Czolgosz was an anarchist who did not believe in governments, rulers, voting, religion, or marriage. In a handwritten confession, he complained that McKinley had been going around the country shouting about prosperity, when there was no prosperity for the working man.

McKinley’s assassination marked the symbolic end of one era in national politics and the beginning of a new one. The 1890s had been a decade of depression, labor strife, and agrarian unrest, and the upheaval was not confined to the United States. The great European powers were struggling to control Africa, the Near East, and the Far East. An attempted revolution took place in Russia. At the turn of the century, six heads of state were assassinated by anarchists.

By 1900, many of the great questions of the nineteenth century seemed to be settled. Corporate enterprise would dominate the American economy, justified by Social Darwinism. The United States had decided to join the global struggle for trade and markets. The status of African Americans was going to be largely defined by white Southerners.

But in fact, the twentieth century would not be a continuation of the nineteenth century. It was obvious from the moment that Theodore Roosevelt became president that new issues would dominate the twentieth century.

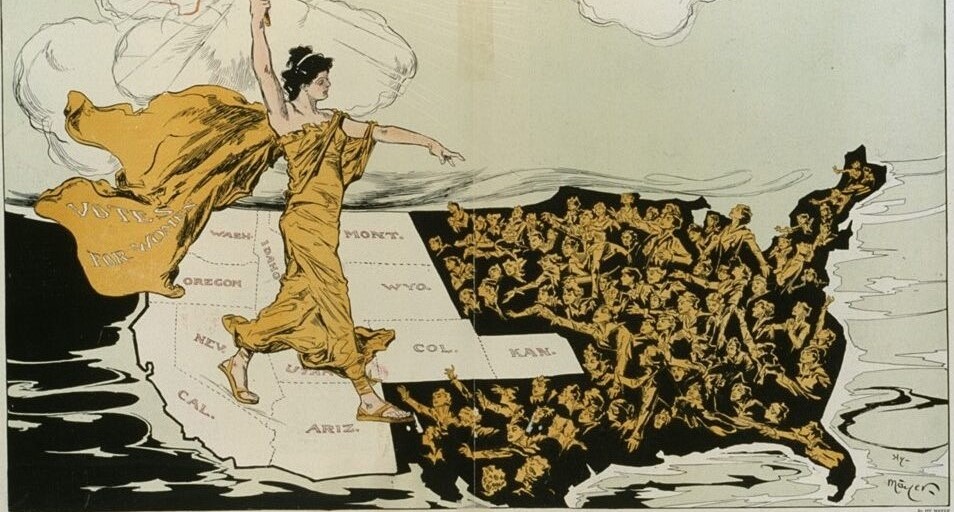

The Progressive era is one of this country’s most far-reaching and comprehensive eras of reform. Reform took place at the city, state, and national levels, encompassing everything from the banking system to conservation and woman suffrage.