The Roots of Progressivism

The Social Gospel

Religious ideas and institutions have always been one of the wellsprings of the American reform impulse. Progressive reformers were heavily influenced by the body of religious ideas known as the Social Gospel, the philosophy that the churches should be actively engaged in social reform. As elaborated by theologians, such as Walter Rauschenbusch, the Social Gospel was a form of liberal Protestantism which held that Christian principles needed to be applied to social problems and that efforts needed to be made to bring the social order into conformity with Christian values.

Muckrakers

Muckraking reporters, exploiting mass circulation journalism, attacked malfeasance in American politics and business. President Theodore Roosevelt gave them the name “muckrakers” after a character in the book Pilgrim’s Progress, “the Man with the Muckrake,” who was more preoccupied with filth than with Heaven above.

Popular magazines, such as McClure’s, Everybody’s, Pearson’s, Cosmopolitan, and Collier’s published articles exposing the evils of American society—political corruption, stock market manipulation, fake advertising, vices, impure food and drugs, racial discrimination, and lynching. Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle exposed unsanitary conditions in the meat packing industry. John Spargo’s Bitter Cry of the Children disclosed the abuse of child laborers in the nation’s coal mines. Lincoln Steffens’ The Shame of the Cities uncovered corruption in city government.

Herbert Croly and The Promise of American Life

If any one book can be said to offer a manifesto of Progressive beliefs, it was Herbert Croly’s The Promise of American Life. Croly (1869-1930), a political theorist and journalist who founded The New Republic magazine. was Progressivism’s preeminent philosopher. Published in 1909, his book argued that Americans had to overcome their Jeffersonian heritage, with its emphasis on minimal government, decentralized authority, and the sanctity of individual freedom, in order to deal with the unprecedented problems of an urban and industrial age. Industrialism, he believed, had reduced most workers to a kind of “wage slavery,” and only a strong central government could preserve democracy and promote social progress.

Croly, like most Progressives, was convinced that only a public-spirited, disinterested elite, guided by scientific principles, could restore the promise of American life. Thus, he called for the establishment of government regulatory commissions, staffed by independent experts, to protect American democracy from the effects of corporate power. He also believed that human nature “can be raised to a higher level by an improvement in institutions and laws.”

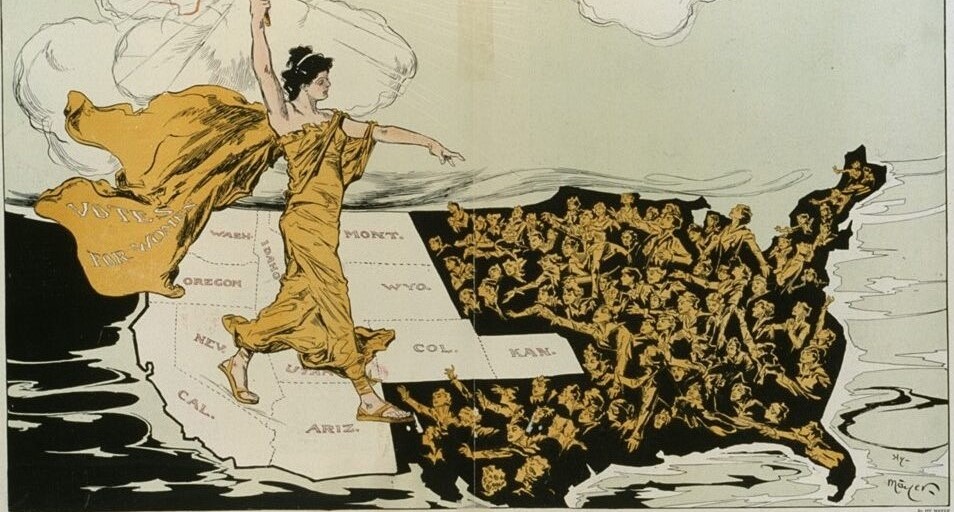

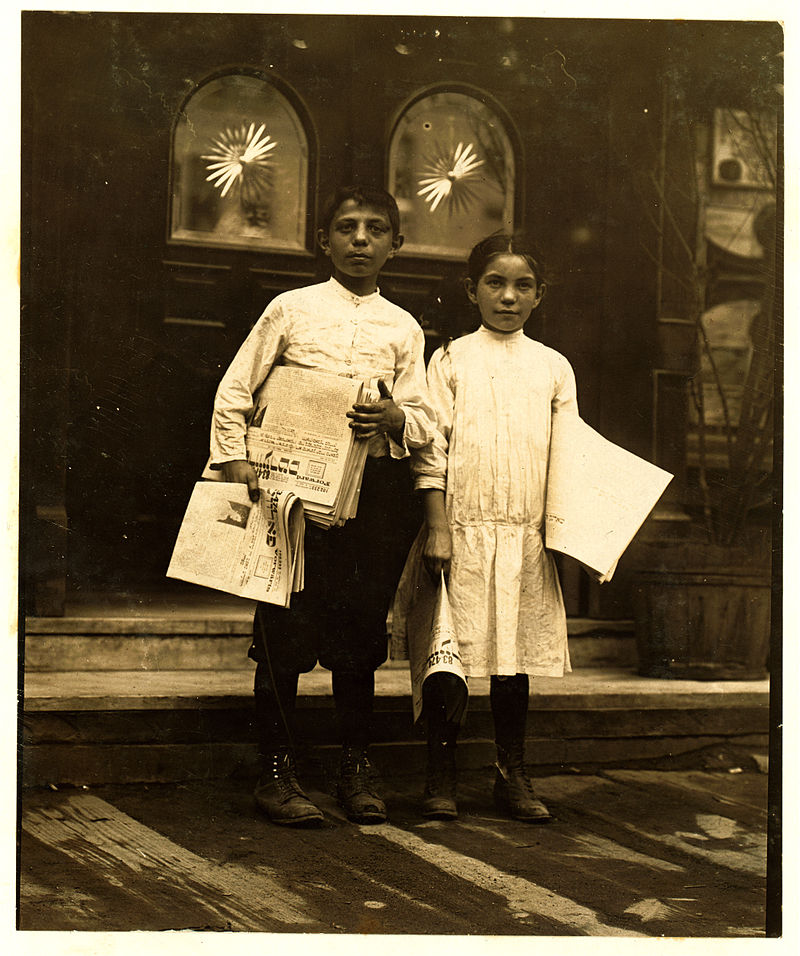

Newsies

In the movies, scrappy, urban newsboys hawk papers with screaming headlines, shouting, “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!” Real newsboys in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, however, were very different from the Hollywood image of lovable street urchins singing and dancing in the streets.

Newsboys first appeared on city streets in the mid-nineteenth century with the rise of mass circulation newspapers. They were often wretchedly poor, homeless children who often shrieked the headlines well into the night and often slept on the street.

In 1866, a reformer named Charles Loring Brace described the condition of homeless newsboys in New York City:

I remember one cold night seeing some 10 or a dozen of the little homeless creatures piled together to keep each other warm beneath the stairway of The [New York] Sun office. There used to be a mass of them also at The Atlas office, sleeping in the lobbies, until the printers drove them away by pouring water on them. One winter, an old burnt-out safe lay all the season in Wall Street, which was used as a bedroom by two boys who managed to crawl into the hole that had been burned.

In 1872, James B. McCabe, Jr., wrote:

There are 10,000 children living on the streets of New York…. The newsboys constitute an important division of this army of homeless children. You see them everywhere…. They rend the air and deafen you with their shrill cries. They surround you on the sidewalk and almost force you to buy their papers. They are ragged and dirty. Some have no coats, no shoes and no hat.

In 1899, several thousand newsboys—who made about thirty cents a day—called a strike, refusing to handle the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. Competing papers lavished coverage on the strikers, who were depicted as colorful characters who spoke in an oddly rendered Irish-immigrant dialect and had names like Race Track Higgins and Kid Fish. The news accounts gave much attention to the exhortations of a pint-sized newsboy and strike leader named Kid Blink (because he was blind in one eye). The New York Tribune quoted Kid Blink’s speech to 2,000 strikers: “Friends and feller workers. Dis is a time which tries de hearts of men. Dis is de time when we’se got to stick together like glue…. We know wot we wants and we’ll git it even if we is blind.”

The lot of newsboys began to improve as urban child-welfare practices took root, and publishers began competing for newsies by giving them prizes and trips.