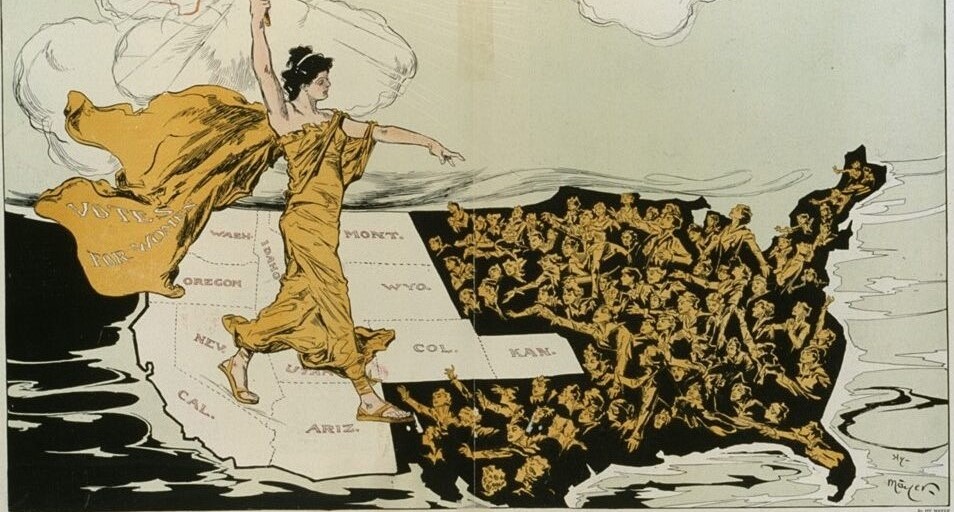

A New Era

A New Era

The turn of the twentieth century witnessed a sudden clamor for social, political, and economic reform. Progressives boldly challenged the received wisdom in every aspect of life.

Birth Control

Of all the changes that took place in women’s lives during the twentieth century, one of the most significant was women’s increasing ability to control fertility. In 1916, Margaret Sanger, a former nurse, opened the country’s first birth control clinic in Brooklyn. Police shut it down ten days later. “No woman can call herself free,” she insisted, “until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother.” Margaret Sanger coined the phrase “birth control” and eventually convinced the courts that the Comstock Act did not prohibit doctors from distributing birth control information and devices. As founder of Planned Parenthood, she aided in the development of the birth control pill, which appeared in 1960.

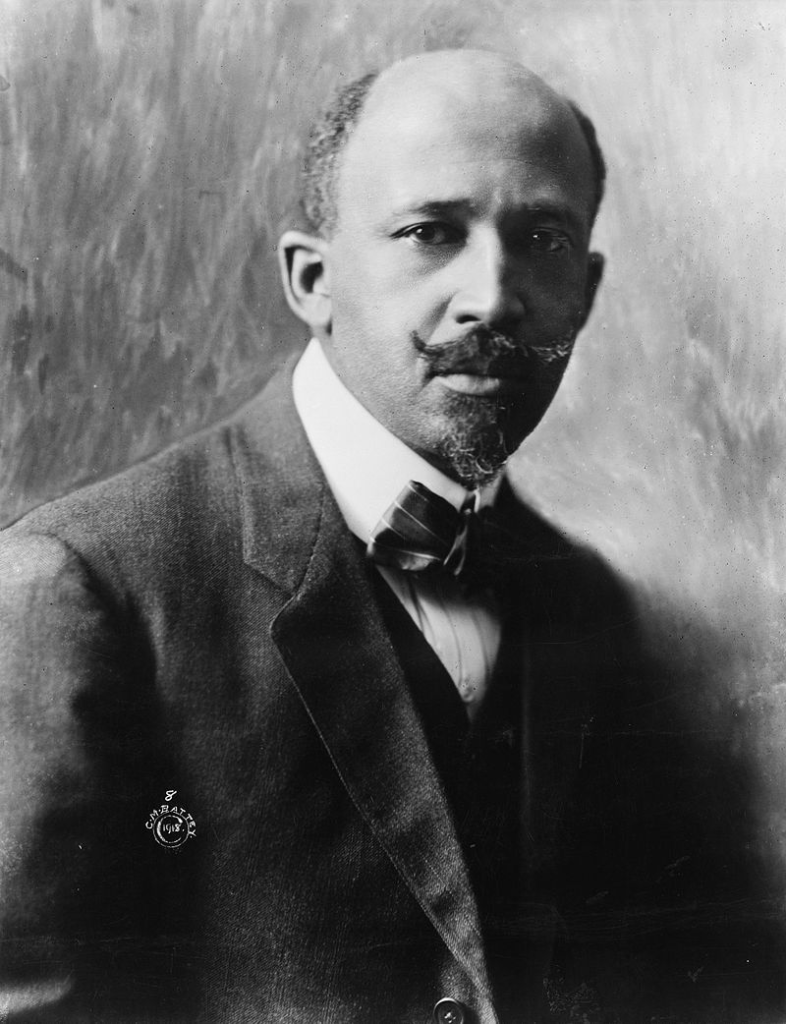

Civil Rights

The publication of W.E.B. DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folk heralded a new, more confrontational approach to civil rights. “The problem of the twentieth century,” DuBois’s book begins, “is the problem of the color line.” In his book, DuBois, the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard, condemns Booker T. Washington’s philosophy of accommodation and his idea that African Americans should confine their ambitions to manual labor.

The Nashville Banner editorialized: “This book is dangerous for the Negro to read, for it will only excite discontent and fill his imagination with things that do not exist, or things that should not bear upon his mind.” In 1908, after anti-black rioting took place in Springfield, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln’s home town, DuBois and a group of African Americans and whites convened at a convention in Harpers Ferry, Virginia The meeting became the basis for the first country’s first national civil rights organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). By 1914, the NAACP had 6,000 members and offices in fifty cities.

Conservation

In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt stated,

We are prone to speak of the resources of this country as inexhaustible; this is not so. The mineral wealth of the country, the coal, iron, oil, gas, and the like does not reproduce itself, and therefore is certain to be exhausted ultimately; and wastefulness in dealing with it today means that our descendants will feel the exhaustion a generation or two before they otherwise would.

During Roosevelt’s presidency, 148 million acres were set aside as national forest lands and more than 80 million acres of mineral lands were withdrawn from public sale.

Government Reform

A Republican governor in Wisconsin, Robert LaFollette, put into effect the “Wisconsin idea,” which provided a model for reformers across the nation. It provided for direct primaries to select party nominees for public office and for a railroad commission to regulate railroad rates. The model also presented tax reform, opposition to political bosses, and the initiative and recall, devices to give the people more direct control over government.

Labor Relations

In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt became the first president to intervene on the side of workers in a labor dispute. He threatened to use the army to run the coal mines unless mine owners agreed to arbitrate the strike. The president handpicked a commission to mediate the settlement.

Medical Education

Abraham Flexner’s 1910 study of American medical colleges transformed the training of doctors. His report led to the closing of second-rate medical schools and to sweeping changes in medical curricula and teaching methods.

Philanthropy

John D. Rockefeller revolutionized philanthropy by setting up a foundation staffed by experts to evaluate proposals and support programs to solve critical public problems. His foundation and others funded social surveys—systematic, non-partisan examination of subjects by experts.

Radical Trade Unionism

“One Big Union for All” was the goal of the radical labor leaders and Socialists who met in Chicago in 1905. This group also formed the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Rejecting the approach of the American Federation of Labor, which only admitted skilled craft workers to its ranks, the IWW opened its membership to any wage earner regardless of occupation, race, creed, or sex.

Socialism

A new political party, the American Socialist Party, was founded in 1901. At its peak in 1912, the party had 118,000 members. The largest socialist newspaper, The Appeal of Reason, published in Girard, Kansas, had a weekly circulation of 761,000. In the 1912 election, socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs received 800,000 votes. Socialists captured 1,200 political offices, including the mayors of 79 cities.

Trust-Busting

In 1902, President Roosevelt instructed his attorney general to file suit against Northern Securities, a railroad holding company, and the Beef Trust in Chicago, for illegal constraint of trade. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ruled on the government’s behalf. A clear message was sent: That monopolies that abused the public would be broken up.

Sight and Sound

Progressivism and Photography

The development of photography in the mid-nineteenth century made images an integral part of American life. Today, it is more important than ever to develop visual literacy and understand how to “read” a photograph.

The first photograph was an image recorded on a pewter plate by a Frenchman, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, in 1826. It showed the view from an upper story window in his home. Great strides in photography would not take place until the next decades, when Louis Daguerre created images on silver-plated copper, coated with silver iodide, which developed with mercury. In daguerreotypes, the images seem to float above the highly polished silver.

At first, there was no agreement about what to call the process of capturing an image. Among the terms bandied about were daugerreotype, crystalotype, talbototype, colotype, crastalograph, panotype, hyalograth, ambrotype, and hyalotype. Ultimately, a new word won out—photography–which means writing with light.

Daugerreotypy was a cumbersome and time consuming process. The biggest problem was that it was impossible to duplicate daguerreotypes. But by the end of the 1850s, the daugerreotype had been replaced by a new method of photography known as the wet plate process. A British photographer named Frederick S. Archer discovered that a glass plate coated with a mixture of silver salts and an emulsion made of collodion could record an image. The image had to be developed immediately, before the emulsion dried. But it was now possible for the first time to make unlimited prints from a negative. It was also possible for photographers to take pictures outside of a studio.

A key figure in early American photography was Mathew Brady, who was just twenty-two years old when he took up photography in 1844. At first, many of his photographs were portraits of famous Americans, such as Senator Daniel Webster. These photographs tended to portray individuals in solemn poses that reflected the republican emphasis on dignity and virtue and made no effort to show the background or setting.

Brady gained lasting fame for his Civil War photographs, which created lasting images of the conflict in terms of rotting corpses and razed cities. Yet however lifelike these pictures seem, we must realize that they were not accurate depictions of wartime realities. Brady carefully arranged the scenes, and even moved corpses to ensure that they appeared where he wanted them.

In 1885, American inventor George Eastman introduces film made on a paper base instead of glass, eliminating the need for glass plates. Three years later, he introduced the lightweight, inexpensive Kodak camera, using film wound on rollers. He also began to develop films in his own processing plants. No longer did amateur photographers have to process their own pictures.

Some professional photographers responded to the growth of amateur photography by attempting to transform the photograph into a work of art. One of the most famous American photographers, Alfred Stieglitz, experimented with camera angles, close ups, and focus to created photographs that resemble impressionist paintings.

Another group of professional photographers used photographs as an instrument of social reform. The two most important early documentary photographers were Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine.

A Danish immigrant, Jacob Riis was the pioneer in the use photography as an instrument of reform. A crusading newspaper reporter who took his camera into urban slums.

Riis gained lasting recognition as a result of a book entitled How the Other Half Lives. In the past, he wrote, “the half that was on top cared little for the struggles, and less for the fate of those who were underneath.” But he wanted to rectify that omission.

Reading Riis’s book today can be a disturbing experience. His book is filled with condescending and insulting generalizations. Italian immigrants were “content to live in a pig-sty.” Chinese immigrants were “in no sense a desirable element of the population. For Eastern European Jews, he wrote, “Money is their God. Life itself is of little value compared with even the leanest bank account.” About African Americans, he wrote, “Poverty, abuse and injustice alike the Negro accepts with imperturbable cheerfulness.”

The son of an Oshkosh, Wisconsin storekeeper, Lewis Wickes Hine was one of America’s most successfully socially-conscious reform-minded photographers. No one was more effective in arousing public passion over child labor than Hine. Hired by the National Child Labor Committee in 1908 to document child labor, he took over 5,000 photographs of children working in agriculture, canneries, coal mines, factories, mills, and sweatshops, mainly in the South. His photographs revealed the brutal conditions of child labor and the inadequacy of existing child labor laws. His photographs awoke the nation’s conscience in a way that statistics and reports had failed to accomplish