Hidden History of Drugs

Hidden History

Hidden History of Drugs

The United States, we are told, is in the midst of an opioid crisis. In 2014, 47,000 Americans died of opioid-related causes. Since 1999, there was a quadrupling of the number of opioids prescribed to treat chronic pain; deaths from prescription opioids also quadrupled.

The history of psychoactive drugs in the United States has followed a curious pattern. There are periods in which the drugs are viewed extremely positively, even euphorically, as a solution to a host of personal and social ills. Then, as problems mount, a reaction sets in, and drug use is severely punished. Then the problems are forgotten and a new surge in drug use appears.

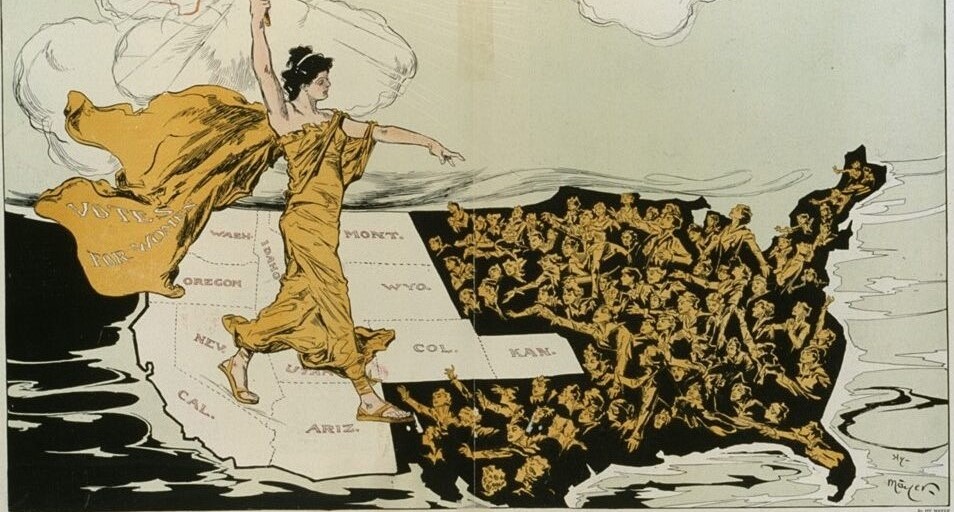

In the late nineteenth century, the United States had no national laws restricting the sale of drugs, and narcotics and other psychoactive drugs, including opium or cocaine, were widely available. Cocaine first became widely available in 1885 and was advertised as a cure for many physical and psychological ailments. A drug manufacturer claimed that cocaine could “supply the place of food, make the coward brave, the silent eloquent, free the victims of the alcohol and opium habits from their bondage, and, as an anesthetic, render the sufferer insensitive to pain…” A leading neurologist echoed those sentiments, claiming that cocaine could “make the most dismal melancholic cheerful and [the cocaine would] act permanently.”

Drugstores sold coca cigarettes and cigars. Not surprisingly, drug use reached levels never equaled in American history. In Eugene O’Neill’s play “A Long Day’s Journey into Night,” set in 1912, the protagonist, Mary Tyrone, is addicted to morphine, a drug obtained from opium.

Laws combined with a growing popular fear of addictive drugs to greatly reduce the use of cocaine and opiates. The early twentieth century saw a surge in public health concerns, with movements to prohibit the manufacture and sale of alcohol, restrict food additive, and ensure pure foods and meats. The first federal drug law, the Food and Drug Act of 1906, required any over-the-counter remedy containing cocaine to list it as an ingredient. In 1914 the federal government, enacted the Harrison Anti-Narcotic Act, which strictly regulated the distribution of opiates and cocaine. Drugs were increasingly associated with gangs and the disreputable. Heroin manufacture was banned in 1924, and the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 criminalized marijuana.

Over time, however, public memory of the earlier drug crisis faded. Around 1970, cocaine use began to rise, culminating in the 1980s in the spread of crack, a smokable crystal form of cocaine, which was associated with a sharp rise in urban crime. The crack epidemic prompted enactment of harsh legal penalties that sharply increased the prison population.