The Struggle for Women’s Suffrage

The Struggle for Women’s Suffrage

Among the most radical of all struggles in American history is the on-going struggle of women for full equality. The ideals of the American Revolution raised women’s expectations, inspired some of the first explicit demands for gender equality, and witnessed the establishment of female academies to improve women’s education. By the early nineteenth century, American women had the highest female literacy rate in the world.

Nevertheless, restrictions on women’s rights remain intact. Married women could not own property, make contracts, bring suits, or sit on juries. They could be legally beaten by their husbands and were required to submit to their husbands’ sexual demands.

During the early nineteenth century, however, a growing number of women became convinced that they had a special mission and responsibility to purify and reform American society. Women were at the forefront of efforts to establish public schools, abolish slavery, and curb drinking. But faced with discrimination within the antislavery movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others organized the first Women’s Rights Convention in history in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848.

The quest for full equality involved not only the struggle for the vote, but for divorce, access to higher education, the professions, and other occupations, as well as birth control and abortion. Women have had to overcome laws and customs that discriminated on the basis of sex in order to overcome the oldest form of exploitation and subordination.

“Failure is Impossible”

Months before her death in 1906, the pioneer suffragist, Susan B. Anthony, told guests at her 86th birthday party not to abandon the fight for the vote for women. “Failure,” she insisted, “is impossible.”

Fifty-five years earlier in 1851, Anthony had met Elizabeth Cady Stanton at a temperance meeting in Seneca Falls, New York. Stanton would persuade her to dedicate her life to women’s rights. Anthony, a school teacher and the daughter of an abolitionist Quaker mill owner, was a brilliant organizer and a tireless orator. She would press on in the face of ridicule and indifference.

In 1854, Anthony collected 10,000 signatures on a petition supporting women’s suffrage and property rights for married women. At the time, the property and even the wages of a married woman in New York State legally belonged to her husband. It would not be until 1860 that New York gave women control over their wages, the right to bring court actions, and guardianship over their children.

During the Civil War, Anthony and Stanton set aside the suffrage issue and worked for passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery. After the war, they were angry when the Fifteenth Amendment failed to give women the right to vote. They refused to support the amendment.

In 1869, they persuaded an Indiana member of Congress to introduce an amendment to establish women’s suffrage. Three years later, Anthony, her mother, her sisters, and a number of friends, voted in Rochester, New York, after persuading a sympathetic male voting registrar that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed equal rights to all citizens. “It is downright mockery,” she said, “to talk to women of the blessings of liberty when they are denied the only means of securing them—the ballot.” Anthony was fined a hundred dollars, but she refused to pay. The judge did not try to collect the fine to prevent her from appealing his decision.

It would not be until fourteen years after Anthony’s death that the women’s suffrage amendment would be ratified—in the Tennessee legislature, by a single vote.

72 Years

There were 72 years of struggle by women and their male supporters before women achieved political equality. In order to win the vote, suffragists had to engage in petitioning, lobbying, politicking, marching, and picketing the White House. They also ran campaigns to defeat anti-suffrage legislators.

Proponents of women’s suffrage waged 480 campaigns in state legislatures to persuade them to adopt suffrage amendments to state constitutions. There were 56 statewide referenda among male voters and 47 campaigns to convince state constitutional conventions to adopt women’s suffrage provisions. There were also 277 campaigns at state party conventions, thirty at national conventions, and nineteen in separate Congresses to get state parties to adopt women’s suffrage planks.

The Drive for the Vote Begins

New Jersey was the only one of the original states to allow any women to vote. Its first constitution granted single and widowed women property holders the right to vote from 1776 to 1807. In 1838, Kentucky authorized women to vote in school elections, and many other states followed suit. In 1848, at the first Women’s Rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, some 68 women and 32 men signed the first formal demand that women receive the right to vote.

The first Women’s Rights convention based its demand for women’s suffrage on natural rights. The Declaration of Sentiments, which the convention issued, enumerated women’s lack of economic and educational opportunities, inequalities in pay and property rights, as well as their lack of representation in government.

When Elizabeth Cady Stanton urged participants at the convention to include voting rights among their demands, many balked. “This will make us appear ridiculous,” one participant cautioned. The suffrage resolution passed, but it was the only one not to receive unanimous approval. Indeed, the resolution would have been defeated if Frederick Douglass had not rallied support for it.

The Movement Splits

After the Civil War, women’s rights supporters split over whether they should push to include women in the Fifteenth Amendment, which extended voting rights to African American men. In 1869, two competing organizations emerged, each with its own strategies and goals. The National Woman Suffrage Association, headquartered in New York and led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, favored a constitutional amendment giving the vote to women as well as to African American men. In addition to a constitutional amendment, this organization advocated an agenda broader than suffrage, including divorce reform, property rights for women, and dress reform. It was wary of men’s involvement in the organization and was willing to forge tactical alliances with Democrats who opposed equal rights for African Americans.

The American Woman Suffrage Association, led by former abolitionist Lucy Stone and based in Boston, believed that the voting rights of black men needed to receive priority. This organization welcomed men into its ranks and favored a state-by-state approach and a single-minded focus on suffrage.

In 1878, Stanton persuaded Senator Aaron A. Sargent of California to introduce a women’s suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It was reintroduced in every session for the next forty years.

The First Breakthroughs

The first breakthroughs for women’s suffrage took place in the West. In 1869, Wyoming territory was the first to give women the vote on equal terms with men. This led Wyoming to call itself the “Equality State” after its admissions to the Union in 1890. Utah territory enacted women’s suffrage in 1873, and Colorado in 1893, where the movement received support from the state’s coal miners, many of whom had lost their jobs during the financial panic of that same year. In Colorado, Caroline Nickols, who edited a newspaper for women called The Colorado Antelope, had written in 1879:

All women are victims more or less; all suffer in one way or another from a preponderance of masculine influence….[men fear] her emancipation will be the death blow to their pet vices and their darling sins.

Idaho adopted women’s suffrage in 1896. Not another state would give women the vote until 1910.

In the West, support for suffrage was intermixed with a variety of seemingly unrelated issues. Some Westerners favored women’s suffrage as a way to attract settlers. Others believed that it would attract women and help “civilize” the region. In Utah, suffrage was related to efforts to maintain a Mormon voting majority within the state.

New Arguments and New Constituencies

In 1890, the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The new organization’s leaders were more pragmatic than their predecessors. Instead of arguing for suffrage in terms of equal rights, they increasingly emphasized arguments based on utility, contending that the vote for women was necessary to clean up politics and fight social evil.

One pro-suffrage cartoon pictured a man sitting on a pier holding a life preserver while women identified as sweatshop workers and “white slaves,” who had been forced into prostitution, drown. Sitting at the man’s side is a woman labeled as anti-suffrage. The cartoon’s caption: “When all women want it, I will throw it to them.”

At times, some suffrage supporters made the ugly argument that giving the vote to women would guarantee that white, native-born voters would outnumber immigrant and non-white voters. Particularly in the South, the struggle for the vote was linked to the issue of race. In Florida, a leader in the suffrage movement argued that “letting the women vote will double the number of white voters and make the colored seem rather small.” In the end, four Southern states did ratify the amendment: Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Texas.

In the North, some suffragists questioned why women could not vote while illiterate and immigrant men could. In nineteenth century America, immigrants who had declared their intention of becoming citizens were allowed to vote in most states.

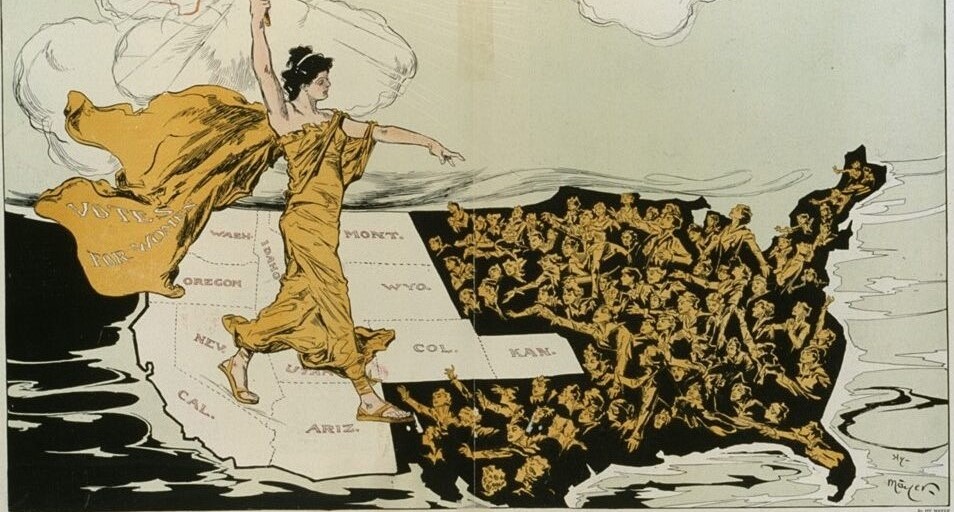

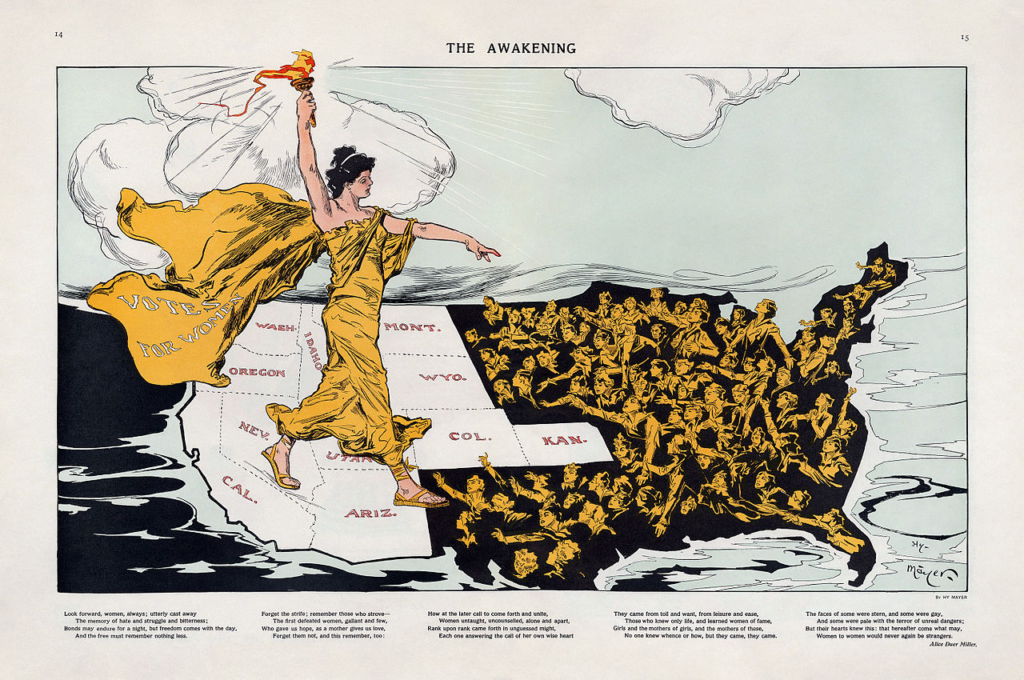

After 1900, the suffrage campaign developed a new, broader constituency, drawing support from many women who had received a college education or who held white collar jobs. Beginning in 1910, a new wave of states adopted women’s suffrage. As in the past, all the states were in the West, including Arizona, California, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. By 1916, eleven Western states had given women the right to vote.

In 1915, Carrie Chapman Catt became head of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. The Iowa-born former schoolteacher had paid her own way through Iowa State College, where she was the valedictorian and the only woman in her class. She married a journalist and after he died, a civil engineer. When she married her second husband, she negotiated a prenuptial agreement that allowed her to work on the suffrage movement away from home four months a year.

Catt developed a new political strategy to win the vote. Called the “Winning Plan,” it involved fighting on two fronts: for state laws that would give women the vote and for ratification of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Her strategy called for referenda campaigns in six states east of the Mississippi River, the defeat of several key senators, and the identification of supporters ready to lobby in every state legislative district in the country.

Meanwhile, a group of younger women grew impatient with the slow pace of change and the cautious approach of the NAWSA and adopted more confrontational tactics. Many of these women had received graduate education abroad, held professional jobs, and were influenced by the example of the militant British suffrage movement. They were led by Alice Paul, a Philadelphia Quaker who formed the National Woman’s Party. Its strategies included picketing, marches, outdoor rallies, and hunger strikes in jail.

On the day of Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration in 1913, Alice Paul organized a protest of 5,000 women, who marched up Pennsylvania Avenue while 100,000 spectators watched. Protesters crossed the barriers that had been set up along the march’s route, heckled the suffragists, and blocked their march. Police refused to come to their aid. Finally, cavalry was called in to allow the march to proceed.

In 1915, some 40,000 women and men marched in a suffrage parade in New York, the largest parade that had ever been held in the city. In January 1917, Alice Paul and her supporters began to picket the White House—the first time this had ever taken place. Six days a week, picketers marched in front of the White House, regardless of the hour or the weather. They carried banners that read: “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty” and “Mr. President, What Will You Do for Woman Suffrage.”

The picketers were physically attacked. In June 1917, some 168 picketers were arrested for obstructing traffic and sentenced to up to six months in jail. When thirty prisoners went on hunger strikes, they were force-fed three times a day with tubes. In 1918, an appeals court struck down the convictions.

The combination of Catt’s careful organizing and Paul’s militant tactics, which included publicly burning copies of speeches by President Wilson, helped to make suffrage an inescapable issue. By 1916, a million American women already had the vote in national elections and were an influential force.

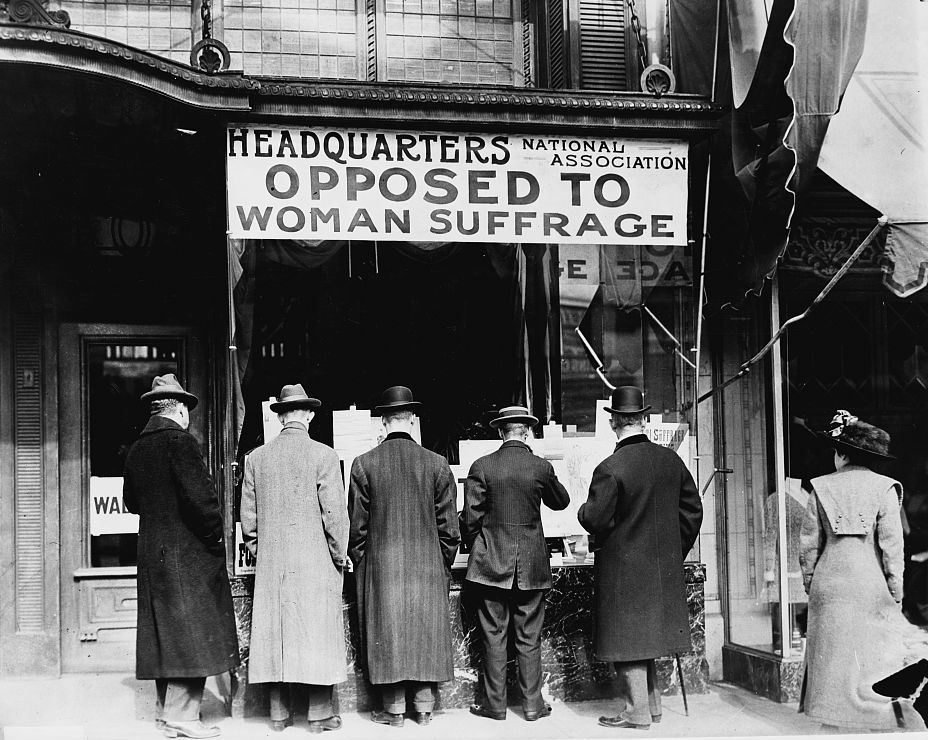

Opponents of Suffrage

Liquor manufacturers and saloon owners opposed suffrage out of fear that women would vote to ban alcohol sales. The suffrage amendment was not ratified until a year after the country adopted prohibition. Some business interests opposed suffrage out of fear that women would vote against the use of child labor and for limitations on work hours.

Many opponents of suffrage argued that politics would debase and de-feminize women and destroy the family. At an 1894 state convention, Kansas Democrats said the vote for women would “destroy the home and family.” In 1918, an Alabama representative predicted:

There will be no more domestic tranquility in this nation. No more “Home Sweet Home,” no more lullabies to the baby. Suffrage will destroy the best thing in our lives and leave in our hearts an aching void that the world can never fill.

Some arguments against suffrage reflected simple gender bias. President William Howard Taft said that he opposed suffrage because women were too emotional. “On the whole,” he wrote, “it is fair to say that the immediate enfranchisement of women will increase the proportion of the hysterical element of the electorate.”

The Final Push

After the United States entered World War I, many suffrage supporters argued that women should receive the vote as a war measure. Adoption of women’s suffrage would prove that the allies were fighting for democracy. In January 1918, President Woodrow Wilson announced his support for a women’s suffrage amendment. That year Michigan, Oklahoma, and South Dakota gave women the vote. Additionally, the House of Representatives ratified a suffrage amendment by the precise two-thirds vote needed for passage.

Ratification was repeatedly defeated in the Senate. It was not until 1919, when Republicans had a majority, that the Senate finally passed what would become the Nineteenth Amendment and sent it to the states for ratification. One member of Congress left his wife’s deathbed to vote on ratification. When he returned home, she was dead.

Within six days of Congress’ ratification of the amendment, six states also ratified the amendment. To become part of the Constitution, the amendment had to be ratified by 36 states. In March 1920, West Virginia, by a single vote, became the 34th state to ratify. Washington State quickly followed.

There appeared to be one state left to go. But Ohio’s state constitution provided for a voter referendum to confirm the legislature’s ratification of a constitutional amendment. Petition drives were mounted in other states to reverse their ratification of the amendment. In June 1920, the Supreme Court ruled that the Ohio referendum provision was unconstitutional, ending the threat of reversals in other states.

All eyes turned to Tennessee, which seemed to be the most likely remaining state to ratify the amendment. At the urging of President Wilson, the governor called a special session. The decisive vote was cast by the assembly’s youngest member, Harry Burn, who was just twenty-four years old and had earlier opposed ratification. He said that he changed his vote after receiving a letter from his mother, urging him to be a good boy and “help Mrs. Catt put rat in Ratification.” The measure passed 49 votes to 47 votes. On August 26, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

In 1920, the United States became the 27th country to give women the vote, after countries such as Denmark, Mexico, New Zealand, and Russia. In fact, most of these countries adopted women’s suffrage during or immediately after World War I.

Did the Vote Make a Difference?

Observers expected a flood of women voters in the 1920 presidential election. In fact, women’s turnout matched that of men, about fifty percent—one of the lowest turnouts in years.

Nevertheless, women’s suffrage did make a difference. Even during the 1920s, women voters showed a special concern for social issues. Women voters were more likely than men to attach priority to issues involving children, education, and health care. They also tended to be strong advocates of peace. The issues that dominated American politics during the 1920s—education, the establishment of maternal and infant health care clinics, pacifism, and prohibition—reflected women’s mounting political influence.

After the adoption of the nineteenth Amendment, Alice Paul went to law school. On the 75th anniversary of the first Women’s Rights convention in 1923, she went to Seneca Falls, New York, and proposed an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution which declared that rights should not be abridged on account of sex. The amendment was introduced in Congress every year from 1923 until 1972.

Who Was the First Woman Senator?

Rebecca Felton of Georgia (1922): A pioneering feminist but also a defender of lynching, she served for a single day.

Hattie Caraway of Arkansas (1932): She was appointed to the Senate following her husband’s death, and subsequently became the first woman elected to the Senate.

Margaret Chase Smith: She was elected to the House of Representatives following the death of her husband, a member of Congress. She was the first woman who was not appointed to the Senate, but was elected in her own right.

Hazel Hempel Abel, a Republican from Nebraska, was the first woman to follow another woman in a Senate seat. She was also the first woman Senator whose husband had not been a member of Congress. However, she only served two months, having agreed not to seek a six-year term. Eva Bowring had previously been appointed to the seat to serve until an election was held.

Nancy Kassenbaum was the first woman ever elected to a full term in the Senate without her husband having previously served in Congress. She was the second woman elected to a Senate seat without it being held first by her husband (Margaret Chase Smith of Maine was first elected to the House of Representatives to fill her husband’s vacancy but later won four Senate elections) or appointed to complete a deceased husband’s term. She was the daughter of a Republican Governor and presidential nominee, Alf Landon.

Barbara Mikulski, who served in Congress longer than any woman in history, was the first woman who was elected to the Senate (in 1986) who did not have a husband or father who served in high political office.

Political Firsts

Many political firsts for women took place in the West. Argonia, Kansas, elected the first woman mayor in 1887. Colorado elected three women state legislators in 1894. Montana elected the first woman to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1916—Jeannette Rankin, a Republican. Wyoming elected the nation’s first woman governor in 1925—Nellie Taylor Ross, a Democrat, who succeeded her deceased husband.

In 1922, Rebecca Felton of Georgia was the first woman appointed to the U.S. Senate. She served for only two days. It was not until 1978, with the election of Republican Nancy Kassebaum of Kansas, that a woman was elected to the U.S. Senate in a general election. Earlier women Senators had been appointed to fill a vacancy or were elected to fill an unexpired term.

Sandra Day O’Connor became the first woman appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1981. Geraldine Ferraro, a New York Democrat, became the first woman nominated for vice president by a major political party in 1984.

Who was the Most Influential Woman in U.S. History?

Harriet Tubman: A key figure in the Underground Railroad.

Harriet Beecher Stowe: Whose novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin energized antislavery sentiment in the North.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Leading figure in the campus for women’s rights.

Susan B. Anthony: A leader in the campaign for women’s suffrage.

Helen Keller: An advocate for those with physical disabilities.

Margaret Sanger: Led the effort to legalize birth control in the United States and the effort to develop the birth control pill.

Eleanor Roosevelt: Advocate for the interests of women, African Americans, and others during the New Deal and World War II and helped draft the 1948 UN Declaration of Human Rights.

Rachel Carson: Her book Silent Spring, on the detrimental effects of pesticides on the environment, helped launch the environmental movement.

Rosa Parks: A Civil Rights activist.

Betty Friedan: Her best-selling book The Feminine Mystique helped spark the rise of the feminist movement.