Overview: The Progressive Era

The United States in 1900

Life expectancy for white Americans was just 48 years and just 33 years for African Americans—about the same as a peasant in early nineteenth century India. Today, Americans’ average life expectancy is 74 years for men and 79 for women. The gap in life expectancy between whites and non-whites has narrowed from fifteen years to seven years.

In 1900, if a mother had four children, there was a fifty-fifty chance that one would die before the age of five. At the same time, half of all young people lost a parent before they reached the age of twenty-one.

In 1900, the average family had an annual income of $3,000 (in today’s dollars). The family had no indoor plumbing, no phone, and no car. About half of all American children lived in poverty. Most teens did not attend school, instead they labored in factories or fields.

The nation’s population was still concentrated in the Northeast. In 1900, Toledo was bigger than Los Angeles. California’s population was the size of the population in Arkansas or Alabama. Today, Sunbelt cities like Houston, Phoenix, and San Diego have outpaced cities like Rochester, N.Y. and Providence, R.I. In 1900, about sixty percent of the population lived on farms or in rural areas. Today, one in four lives in rural areas. More than half live in suburbs.

The top five names in 1900 for boys were John, William, James, George and Charles. For girls, they were Mary, Helen, Anna, Margaret, and Ruth—almost entirely traditional biblical and Anglo-Saxon names. The top five names today: Michael, Jacob, Matthew, Christopher, and Joshua for boys; Emily, Samantha, Madison, Ashley, and Sarah for girls. These names still reflect the strong influence of the Bible on naming-patterns but also the growing influence of entertainment. Florence and Bertha no longer even make the top 10,000 list of names.

In 1900, two of America’s ten biggest industries were boot making and malt liquor production. There were only 8,000 cars in the country—none west of the Mississippi River. Dot-com communication still meant the telegraph.

Twentieth Century Revolutions

The twentieth century was a century of revolutions. We usually think of revolutions in terms of banners and barricades, and the twentieth century certainly witnessed social and political upheavals, including the Russian and Chinese Revolutions. But many of the century’s most lasting revolutions took place without violence. There was the sexual revolution, a civil rights revolution, the women’s liberation movement, and the rise of the giant corporation, big labor, and big government. Revolutions in technology, science, and medicine utterly transformed the way people lived.

The scientific revolution is perhaps the most obvious development. During the 1890s, physics and medicine radically changed our view of the world. The discovery of X-rays, radioactivity, sub-atomic particles, relativity, and quantum theory produced a revolution in how scientists viewed matter and energy. Medicine, too, underwent a radical transformation, as laboratory-based science reshaped medical practice. Scientists identified the first virus and research in scientific medicine first led to a cure for yellow fever. Then, it largely eliminated polio and smallpox.

Humankind developed air transport, discovered antibiotics, and invented computing. It also split the atom and broke the genetic code. Communication technology was revolutionized with the telephone, the radio, television, and the Internet. Contraceptives separated sex from procreation. The rapid spread of the automobile also modernized transportation technology.

The twentieth century also witnessed a revolution in economic productivity. Between 1900 and 2000, the world’s population roughly quadrupled—from almost 1.6 billion to 6 billion people. But global production of goods and services rose fourteen or fifteen-fold. In 1900, the Standard & Poor’s 500 index stood at 6.2. In 1998, the index was 1085.

Technological improvements shrunk the average work week by a day and a half. Technology also opened the workplace to increasing numbers of women, especially married and older women.

Equally important was the rise of mass communication and mass entertainment. In 1900, each person made an average of 38 telephone calls. By 1997, the figure had grown to 2,325 phone calls. In 1890, there were no billboards, no trademarks, and no advertising slogans. There were no movies, no radio, no television, and few spectator sports. No magazine had a million readers. The 1890s saw the advent of the mass circulation newspaper, the national magazine, the best-selling novel, many modern spectator and team sports, and the first million-dollar nationwide advertising campaign. In 1900, some 6,000 new books were published. By the end of the century, the number had increased more than ten-fold.

The twentieth century also brought about a revolution in health and living standards. The latter part of the nineteenth century was an era of tuberculosis, typhoid, sanitariums, child labor, twelve-hour work days, tenements, and outhouses. In 1900, more Americans died from tuberculosis than from cancer. Each day millions of horses deposited some twenty-five pounds of manure and urine on city streets. Life expectancy increased by thirty years. Child mortality fell ten-fold. In 1900, families spent an average of 43 percent of their income on food. Now, they spend fifteen percent.

The expansion of government was one of the twentieth century’s most striking developments. In 1900, the U.S. government took in just $567 million in taxes. In 2018, the total was over $3 trillion. Government spending as a share of Gross Domestic Product (the measure of wealth created) in 1913 ranged from 1.8 percent in the U.S. to 17 percent in France. At the end of the century, it ranged from 34 percent in the United States to 65 percent in Sweden.

Less pleasantly, the twentieth century also saw a visible increase in the human capacity for violence. In 1900, British commander Horatio Kitchener came up with a new strategy in the Boer War in South Africa. He rounded up 75,000 people, mostly women and children, and confined them to prison camps where most quickly died. They were the first victims of one of the twentieth century’s most destructive inventions: the concentration camp.

The turn of the century also introduced genocide—the deliberate attempt to exterminate an entire people. In 1904, in the German colony of South-West Africa, now Namibia, the Kaiser’s troops systematically exterminated as many as 80,000 Herero. This slaughter produced forced labor camps, sex slaves, and the first academic studies of supposed Aryan superiority. After poisoning the water holes, the Herero were driven into the desert and were bayoneted, shot, or starved. Those not killed—20,000 Herero—were condemned to slavery on German farms and ranches.

The human capacity for mass killing increased exponentially as a result of improved weaponry and the increased power of the state. The twentieth century was scarred by gulags, concentration camps, secret police, terrorism, genocide, and war.

Technology helped make the twentieth century the bloodiest in history. World War I, which introduced the machine gun, the tank, and poison gas, killed ten million (almost all were soldiers). World War II, with its firebombs and nuclear weapons, produced 35 million war deaths. The Cold War added another seventeen million deaths to the total.

Technology made mass killing efficient. Ideologies and ethnicity justified it. Underdeveloped countries driven to modernize quickly were often scenes of repression and sickening mass killing, whether they were communist or non-communist.

A Century of the Young

Among the new words that entered the English language during the twentieth century were “adolescence,” “dating,” and “teenager.” For the first time there was a gap between puberty and incorporation into adult life.

In 1900, children and teenagers under the age of sixteen accounted for 44 percent of the population. Today, the young make up 29 percent. In 1900, less than two percent of young people graduated from high school.

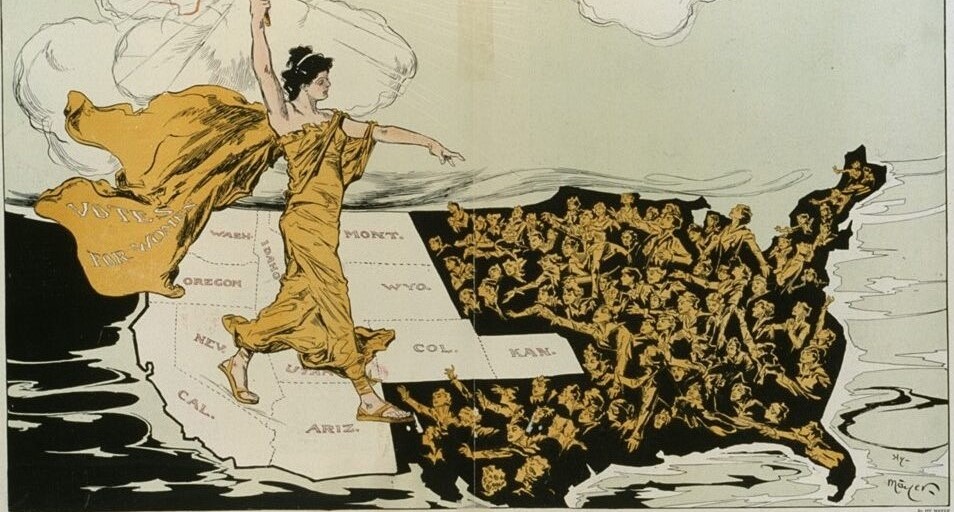

A Century of Women

In 1900, American women could vote in only four Western states. Just 700,000 married women (six percent) were in the paid labor force. Today, the figure is 34 million (64 percent).

In 1900, women accounted for one percent of lawyers and six percent of doctors. At the end of the century, those percentages had risen to 29 percent and 26 percent, respectively. The number of women with bachelor’s degrees increased by half, with women now earning almost sixty percent of such degrees. Today, women with comparable work and work histories as men earn 98 cents for every dollar that men do.

A Century of Prosperity

Despite an economic depression of unprecedented depth, the twentieth century was a century of an extraordinary improvements in health and increases in prosperity. The average lifespan increased by thirty years, from 47 years to 77 years. Infant mortality decreased by 93 percent, and heart disease deaths were cut by half.

The per person Gross Domestic Product was almost seven times higher in 1999 than in 1900. Manufacturing wages, in today’s dollars, climbed from $3.43 per hour in 1900 to $12.47 in 1999. This did not include the growth in fringe benefits such as vacation, medical insurance, and retirement benefits. Household assets—everything from the value of our homes to our personal possessions—were seven times greater. Meanwhile, home ownership increased by 43 percent. In 1900, only one percent of Americans invested in public companies or mutual funds. By the end of the century, the proportion of shareholders exceeded fifty percent.

At the beginning of the century, forty to fifty percent of all Americans had income levels that classified them as poor. At the end of the century, that was cut to between ten and fifteen percent. Until the twentieth century, large numbers of working class men and women faced “the poor house” at the conclusion of their working lives. Today, thanks to social security and retirement plans, most Americans can expect to enjoy a period of more than a decade when they no longer have to work.

During the twentieth century, household incomes of African Americans increased ten-fold. Although African Americans still earn less than whites, the gap has decreased. In 1900, blacks earned about forty percent of what whites earn. Today, they earn about eighty percent of what whites earn.

The average length of the work week decreased by thirty percent, falling from 66 hours to 35 hours. With the introduction of more holidays and a shorter work week, the average number of hours worked in a year is half of what it was in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Meanwhile, the percent of workers on the farm fell by 93 percent.

The percentage of households with electricity went from ten percent to near universal. At the same time, the average American in 1900 had to work six times as many hours to pay his electric bill than did an American a century later.

The number of telephone calls per capita increased 5,600 percent. The number of households with cars increased ninety-fold. The percentage of people completing college was four times higher. Today, more people (28 percent) have bachelor’s degrees than the number of Americans who held high school degrees in 1900 (22 percent).

The Expansion of Freedom

Perhaps the greatest of all twentieth century revolutions was an expansion in human freedom and its extension to new groups of people. Vast strides were made in civil rights, women’s rights, and civil liberties.

European imperialism and colonial empires came to an end. In 1900, the British Empire contained roughly 400 million people, about a quarter of the world’s population. Lesser empires, including the Austro-Hungarian, the Ottoman, and the French, ruled large parts of the globe. In the span of less than twenty years, Europe had partitioned nine-tenths of Africa. France ruled Southeast Asia. The Netherlands established rule in Indonesia and part of New Guinea. Japan established a colonial empire in Korea, Manchuria, Taiwan, and many Pacific Islands. Not to be left out, the United States acquired the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico as a result of war with Spain, and also annexed Hawaii.

At the start of the twenty-first century, 88 of the world’s 191 countries were free. These countries are home to 2.4 billion people—about forty percent of the total world population. These nations enjoy free elections and the rights of speech, religion and assembly.

The very meaning of freedom expanded in the twentieth century. In the nineteenth century, freedom’s meaning was surprisingly limited. It referred simply to equality before the law, freedom of worship, free elections, and economic opportunity. Subsequently, early twentieth century reformers argued that individual freedom could only be realized through the efforts of an activist, socially-conscious state. Freedom increasingly was seen to depend on government regulation, consumer protection, minimum wage, and old-age pensions.

Free speech became a major issue during World War I, largely because of socialists agitating against the war, labor radicals struggling for the right to strike, and feminists seeking to end broad restrictions on contraception.

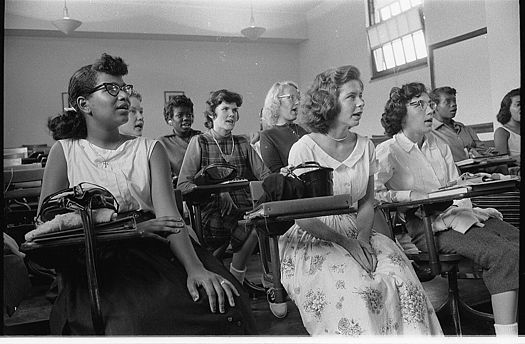

World War II brought the most basic contradiction in American life to a head. It underscored the jarring discrepancy between American ideals of equality and the realities of discrimination, racial exclusion, and inequality. In a series of decisions, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the white-only primary, restrictive covenants that barred blacks and Jews from segregated neighborhoods, and most significant of all, separate schools for African American students.

The conflicts in Korea, Vietnam, Guatemala, the Belgian Congo, and the clashes during the Cold War cost millions of lives. But these struggles had an ironic consequence: they doomed Europe’s empires, and they ultimately reinvigorated the idea of freedom.

During the 1960s, notions of rights extended still further. The discourse of rights expanded to include gay rights, abortion rights, the right to privacy, and the rights of criminal defendants.

At the end of the century, a process of democratization took place on a global scale. “People power” led to the overthrow of the corrupt Marcos regime in the Philippines and the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. The 1990s witnessed the end of apartheid in South Africa, the weakening of clerical tyranny in Iran, the overthrow of dictatorship in Indonesia, and the liberation of East Timor.

Immense attitudinal changes also took place during the twentieth century. Ecological consciousness grew, thus, leading people around the world to recognize that the world’s resources are not limitless. New standards of human rights spread, transcending race, ethnicity, nationality, and gender.