Levittown

Levittown

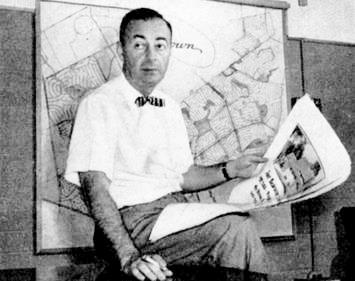

On the morning of March 7, 1949, builder William J. Levitt opened a sales office for a new development of inexpensive single-family homes in a potato field in the center of Long Island’s Nassau County outside of New York City. In bitter-cold weather, more than a thousand young couples crowded outside the sales office, waiting for a chance to buy a four-room, 25-by-32-foot house for $6,999—government financed, no money down. Some had camped out in tents for as long as four days.

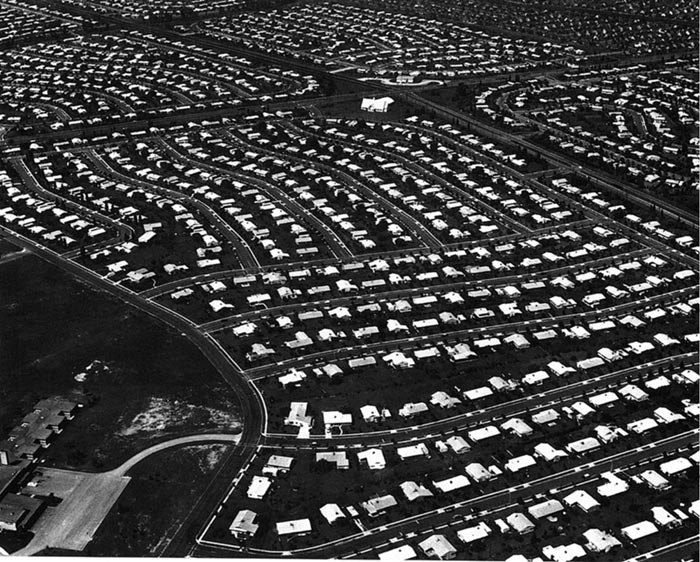

To build houses rapidly and inexpensively, Levitt used the method made famous by Henry Ford: the production line. Levitt broke down the construction of a home into 26 separate steps. Teams of construction workers leveled the land, paved streets, poured concrete slabs, planted trees every 28 feet, and installed plumbing and electrical wiring. A hundred houses were built at a time. Construction was governed by clockwork. By 8 a.m., trucks unloaded prefabricated siding at each house site, at 9:30 a.m., toilets arrived, at 10 a.m., sinks, tubs and Sheetrock™ were delivered, and at 11 a.m., flooring was sent. To speed construction and trim costs, painters used spray guns instead of brushes, and carpenters used power saws. Interior partitions, roof trusses, and door and window units were cut to the required shape before they left the factory.

In order to give young couples a chance to buy an affordable house, Levitt cut costs by eliminating basements and giving all houses in his development the same floor plan. Interior and exterior painting was limited to a single two-tone color scheme. Critics derided the monotony and uniformity of this new suburban development. A popular song “Little Boxes” described suburban homes as “all made out of ticky-tacky and they all looked just the same.” Nevertheless, newlyweds caught in the post-war housing shortage flocked to Levittown by the thousands. When the first phase of construction was completed, 17,500 families had moved in. A second massive development, near Philadelphia, housed 70,000 people. These communities refused to sell to African Americans and reinforced the racial segregation of American housing.

One of the most profound social changes of the post-war era was the rapid growth of suburbs. In the ten years following 1948, some thirteen million homes were built in the United States. Eleven million (85 percent) were built in the suburbs. By 1960 as many Americans lived in the suburbs as in central cities, and the suburban way of life was shaping the patterns and rhythms of American life.

Suburbs, which only began to emerge as fringe communities around central cities in the late 1940s, became the country’s main hometown. In 1940, most Americans lived on farms, small towns with fewer than 2,500 inhabitants, or in big cities. But by 2000, four Americans in five live in suburbs.

The federal government had a great deal to do with the spread of the population into the suburbs, as it made mortgage money available at low interest rates through the Veterans Administration and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Administration. This, combined with an abundance of cheap energy for automobile transportation and state and federal policies that encouraged highway construction, propelled many middle-class Americans into the suburbs.

In 1947, the United States had, by far, the world’s most productive and prosperous economy. With six percent of the world’s population, the U.S. had produced fifty percent of the world’s manufactured goods, 57 percent of its steel, 62 percent of its oil, and over 80 percent of its cars. The average American made fifteen times as much as the average European. Yet, many Americans looked to the future with anxiety. Many Americans feared that the end of heavy wartime spending would bring a return of the economic depression.

Post-war labor strife and inflation contributed to a sense of foreboding. Americans had saved $44 billion during World War II, and pent-up demand caused inflation to soar. By 1948, prices were 48 percent higher than they were in 1945.

Adding to this anxiety was a wave of labor strikes. In January 1946, the automobile, electrical appliance, meatpacking, and steel workers all went on strike. Congress responded to the labor strife by enacting the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, over President Truman’s veto. Opposed by organized labor, the act restricted union activities, such as mass picketing and boycotts, and allowed states to pass “right to work” laws making it illegal to require workers to join unions. It also allowed the attorney general to seek court orders delaying for eighty days any strike endangering public health or safety.

The federal government would take aggressive steps in the post-war period to stimulate economic growth and to ensure that the country would not return to high levels of unemployment. By encouraging the growth of suburbs and of the Sunbelt, these policies transformed the country’s face.

The Rise of the Sunbelt

In 1950, California was the size of Pennsylvania. Florida ranked 21st in size. Now, California is by far the largest state in population and Florida ranks fourth.

One of the central developments of the second half of the twentieth century was the shift in political and economic power from the older industrial cities of the Northeast and Midwest to the South and West. From 1964 to 2008, every elected U.S. president has been born or has claimed residence in the Sunbelt.

At the end of World War II, the South was the nation’s poorest region, with per capita income barely one-half of the national average. Air conditioning, lower taxes and wages, desegregation, and weaker unions contributed to the postwar growth of the South. So, too, did government spending. During World War II, the federal government invested almost $9 billion in the South, mainly in defense plants, shipyards, oil refineries, and chemical plants. As recently as 1980, nearly half of the nation’s soldiers were stationed in the South, and the Defense Department spent nearly forty percent of its budget in the region.

The West also prospered as a result of an infusion of federal dollars. Government spending in the West began to increase steeply during the 1930s, as the Roosevelt administration financed major dam, power, and irrigation projects. World War II accelerated the West’s growth. During the war years, the federal government spent $70 billion in the Western states, over half in California. Southern California’s defense and aerospace industries created more than 250,000 new jobs during the war.

The Interstate Highway System

In 1956, President Dwight Eisenhower authorized the largest public works project in the history of the world. The president had been impressed by Hitler’s autobahns and believed that a national system of highways was necessary to move troops and military equipment and to provide evacuation routes during national emergencies.

In 1919, it took Eisenhower 62 days to travel over mostly unpaved roads from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco. Today, the same trip takes 72 hours.

Presently, there are 46,300 miles of interstate highways, which initially cost $129 billion to build. The federal government paid ninety percent of the system’s construction costs. Unlike older highways, the interstate had no intersections or traffic signs. To ensure that traffic would not have to stop, engineers had to build more than 55,000 bridges or overpasses.

The Interstate Highway System changed the nation’s landscape. Instead of taking trains or buses, workers commuted by cars. Suburbs flourished, and so did suburban sprawl. Shopping centers appeared, like the Detroit shopping center, Northland, that opened with a hundred stores in 1954. At the same time, highways slashed through the hearts of the nation’s cities, cutting through lower-economic class neighborhoods, dividing communities, and facilitating white-flight to the suburbs.