A Struggle for Hearts and Minds

Kefauver Committee

In May 1950, at the very moment that Senator Joseph McCarthy was beginning his crusade against Communist subversion, the U.S. Senate created a special committee to investigate another “enemy within”: organized crime.

Crime statistics suggested that the nation was in the midst of an unprecedented wave of violence. Criminologists attributed a surge in burglary, murder, and prostitution to such factors as the wartime disruption of families, shortages of goods, and a continuing public demand for illicit gambling. But journalists and citizen crime commissions identified another villain, organized crime.

For fifteen months, a committee headed by Tennessee Democrat Estes Kefauver held hearings in fourteen major cities. Television made the committee’s hearings among the most influential in American history. As many as twenty to thirty million Americans watched spellbound as crime bosses, bookies, pimps, and hit-men appeared on their television screens. Americans listened intently as the committee’s chairman informed them that “there is a secret international government-within-a-government” that controlled gambling, vice, and narcotics trafficking, all of which were protected by corrupt police officers, judges, and politicians.

The Kefauver Committee failed to produce effective crime-fighting legislation. It did, however, lead the Special Rackets Squad of the FBI to launch 46,000 investigations and helped defeat proposals to legalize gambling in Arizona, California, Massachusetts, and Montana.

The investigations also helped popularize the myth that organized crime was an alien import, brought into the United States by Sicilian immigrants in the form of the Mafia, a highly centralized, secret organization that used violence and deceit to prey on the public’s weaknesses. In fact, the committee’s conclusion—that organized crime was rooted in a highly centralized ethnic conspiracy—was in error. Most organized crime in the United States is organized on a municipal or regional, rather than a national, basis. And despite the image portrayed in such novels as Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, diverse ethnic groups have participated in gambling, loan sharking, narcotics trafficking, and labor racketeering.

In recent years, the power of the nation’s traditional Mafia families has dwindled. The decline of the mob, however, has not meant the end of organized crime. Rival crime groups have stepped in and taken over such activities as illegal gambling and drug dealing.

Emmett Till

On August 28, 1955, Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old African American youth who was on a summer vacation from his home on Chicago’s South Side, was kidnapped by two white men from his uncle’s home in LeFlore County, Mississippi. Four days later, Till’s badly beaten body was recovered from the Tallahatchie River. A 75-pound cotton gin fan was attached with barbed wire to his neck.

Till had allegedly entered a grocery store, bought some bubble gum, and whistled at a white woman who worked there. The woman’s husband and his half-brother kidnapped and killed Till. As one put it: “I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice.” An all-white jury acquitted the two men in an hour and seven minutes. One juror commented: “If we hadn’t stopped to drink a pop, it wouldn’t have taken that long.”

Emmett Till’s mother held an open-casket funeral. Thousands of African-American Chicagoans attended the viewing, and the African-American press closely followed the episode. Jet magazine even published a picture of the mutilated corpse. In the African-American community the Till murder case became a cause célèbre. To many Americans, white as well as black, Till’s murder and the failure to convict his killers raised the question of whether African Americans could receive equal justice and full civil rights in the United States.

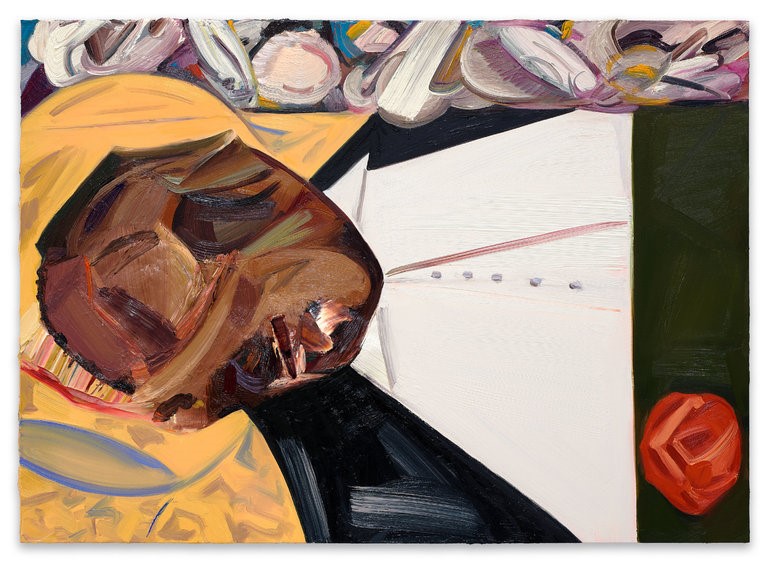

A painting entitled “Open Casket” by the artist Dana Schutz aroused controversy in 2017, with critics arguing that a white artist was commercially exploiting Emmitt Till’s murder and defenders claiming that it spoke to issues of race and violence.

Hearts and Minds

The Cold War was a struggle for the hearts and minds of people across the globe. By the early 1960s, a third of the world’s population lived under Communism and another third lived in non-aligned countries. Public service advertisements on television showed Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev warning Americans that their grandchildren would live under Communism.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union exploited the glaring discrepancy between American ideals of liberty and equality and the harsh reality of racial discrimination. During the late 1940s and 1950s, there were strenuous efforts to bring American realities in line with the country’s founding ideals. In May 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that restrictive covenants prohibiting the sale of homes to blacks and Jews are not legally enforceable. Two months later, President Truman issued Executive Order 9981, ending segregation in the U.S. armed forces.

The Integration of Professional Sports

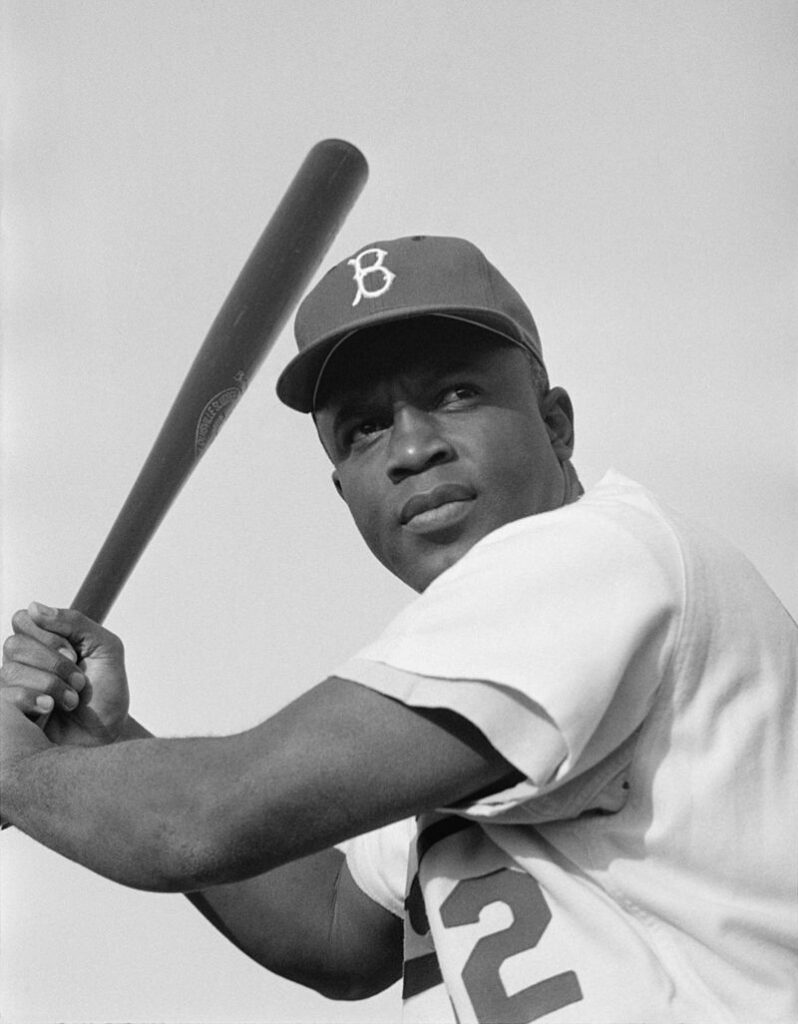

The 1947-1948 baseball season opened with a new Brooklyn Dodger at second base: Jackie Robinson, the first African American in the major leagues. For the first time in the twentieth century, professional baseball—the national pastime—was integrated.

Since the late nineteenth century, pro-baseball and other professional sports had barred black players. The only venues open to black professional athletes were the Harlem Globetrotters, the “clown princes” of basketball, and segregated black teams.

In 1946, when the football Rams moved from Cleveland to Los Angeles, they signed two black football stars from UCLA, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. In 1950, the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball League signed Chuck Cooper, and the New York Knicks signed Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton. In the wake of the defeat of the Nazis and their abhorrent racial policies, American professional sports were integrated.

The Peace Corps

Some 150,000 Americans have served in the Peace Corps since it was formed in 1961. Peace Corps volunteers live and work for two years in communities in the developing world. They must learn the languages of the people they serve. They have worked in 132 nations. In its early years, as many as 15,000 volunteers worked in schools, clinics, and in agricultural and environmental projects.

The Peace Corps was a product of the Cold War. A week before the 1960 presidential election, John F. Kennedy observed that the Soviet Union had “hundreds of men and women, scientists, physicists, teachers, engineers, doctors, and nurses…prepared to spend their lives abroad in the service of world communism.” The United States had no equivalent. Kennedy feared that the United States was in danger of losing the battle for the hearts and minds of the world’s peoples.

He believed that a “peace corps” was the answer. “I am convinced,” he said, “that our men and women, dedicated to freedom, are able to be missionaries, not only for freedom and peace, but to join in a worldwide struggle against poverty and disease and ignorance.”

When John F. Kennedy proposed creating the Peace Corps during the 1960 presidential campaign, the Wall Street Journal asked: “What person can really believe that Africa aflame with violence will have its fires quenched because some Harvard boy or Vassar girl lives in a mud hut and speaks Swahili?” But today, many believe that the Peace Corps volunteers are this country’s best ambassadors.

History Through…

…Political Cartoons