Domestic Communism

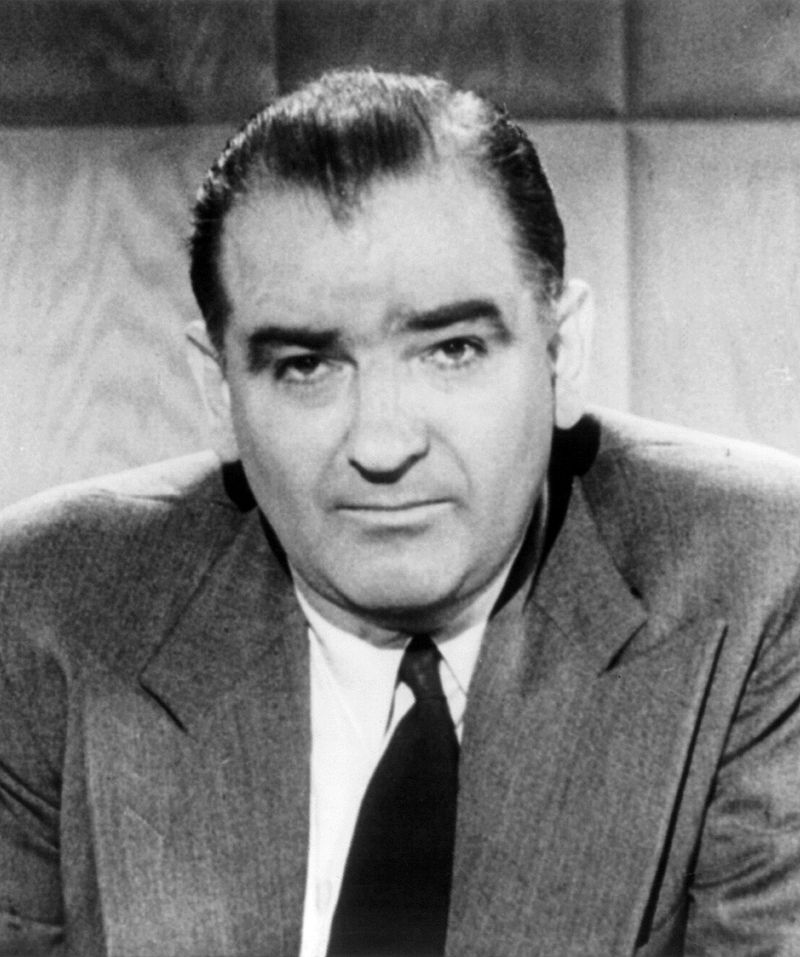

Tail-Gunner Joe

Joseph McCarthy could destroy political careers on a whim. Even the president of the United States treaded warily around him. Dwight D. Eisenhower said of McCarthy: “Never get in a pissing match with a skunk.”

A charismatic demagogue, Joe McCarthy grew up on a Wisconsin farm and attended a one-room schoolhouse. While still a teenager, he established a thriving business as a chicken farmer. He dropped out of school after eighth grade, but returned at the age of twenty and finished four years of schoolwork in just nine months. He worked his way through law school and, at the age of thirty, became the youngest circuit court judge in Wisconsin history. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the Marine Corps and served as an intelligence officer in the South Pacific. In 1946, at the age of 38, he was elected to the U.S. Senate.

McCarthy had an unsavory side. While a Marine, he forged a letter from his commander to obtain a citation for a phony combat wound. He also cheated on his taxes and violated campaign laws.

In an address in 1950 to a Republican women’s club in Wheeling, West Virginia, Senator Joseph McCarthy, R-Wisconsin, claimed to have a list of a great many “known Communists” employed by the State Department:”I have here in my hand a list of 205—a list of names that were known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who are nevertheless are still working and shaping the policy in the State Department.”

When asked by a reporter to produce his list, McCarthy replied: “That was just a political speech to a bunch of Republicans. Don’t take it seriously.”

McCarthy’s stock-in-trade was reckless accusations. Centering around Communist victories in China and Eastern Europe in the late 1940s, McCarthy charged that Secretary of State Dean Acheson had sold the country out to the Communists, that the Truman administration was riddled with subversives, and that the men who guided the country for the previous twenty years were dupes of the Communists. In 1951, Senator McCarthy called George C. Marshall a Communist agent. Senator Millard E. Tydings, D-Maryland, attacked McCarthy for perpetrating “a fraud and a hoax.”

In 1954, McCarthy charged that a Communist spy ring was operating at a U.S. Army Signal Corps installation in New Jersey. McCarthy also accused the Secretary of the Army of concealing evidence. The Secretary retained a Boston attorney, Joseph Nye Welch, to represent him. When McCarthy made a vicious charge, Welch said: “Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or recklessness…. Have no sense of decency, sir, at long last?”

Much of McCarthy’s strongest support came from Catholics of east European descent who were appalled by Communist expansion into their ancestral countries and who viewed McCarthy as a populist figure who stood up to East Coast elites who had failed to stand firm against Communist expansion abroad or subversion at home.

The Second Red Scare

Senator Joseph McCarthy did not create the national obsession with Communist subversion. It had arisen in the late 1930s, years before McCarthy had come to public notice. Angry that they had been barred from the corridors of power for twenty years, conservative Republicans used everything they could to discredit the Roosevelt and Truman administrations. Opponents of the New Deal were not always scrupulously careful to distinguish between liberals and Communists and used anti-Communism as a way to attack labor unions and liberal social programs.

In fact, most liberals did not deny the threat of domestic and global Communism. Most adopted a staunchly anti-Communist stance from the middle 1940s onward. Labor leader Walter Reuther employed stern measures to purge Communists from the CIO in the 1940s. And even the perennial Socialist Party presidential candidate, Norman Thomas, supported efforts to ban Communists from teaching positions on grounds that they had surrendered their right to academic freedom through subservience to Moscow.

The Hatch Act of 1938 made membership into the Communist Party grounds for refusal of federal employment. That same year, the House of Representatives established the House Committee on Un-American Activities to investigate Communist and fascist subversion. Two years later, the Smith Act made it a federal offence to advocate the violent overthrow of the government. In 1949, under the Smith Act, eleven top U.S. Communist Party members were sent to prison for up to five years.

Investigations by executive agencies into the loyalty of federal employees began as early as 1941. Executive Order 9835, signed in 1947 by President Truman, called for a loyalty investigation of all federal employees. Truman hoped that these investigations would help to rally public opinion behind his Cold War policies, while quieting those on the right who thought that the Democrats were soft on Communism. Of the three million government employees who were investigated, 308 were fired as security risks.

If the president had thought that his investigation would end the call to rid government of subversive influences, he was wrong. Accusations that a former high state department official named Alger Hiss had passed classified documents to Soviet agents fueled fears of subversion.

Alger Hiss

In August 1948, Whittaker Chambers, a Time magazine editor and a former Communist, told the House Un-American Activities Committee that Alger Hiss, a former State Department official and president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, supplied Soviet agents with classified U.S. documents.

A federal grand jury indicted Hiss for perjury after Chambers produced a microfilm he had kept hidden in a pumpkin on his Maryland farm. The microfilm contained photographs of the documents Hiss allegedly passed to Chambers. Hiss’s first trial ended in a hung jury, but in 1950, he was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison. The Hiss case was offered as proof that there had been Communists in high government positions.

Anti-Communism During the Early 1950s

In February 1950, Senator Joseph R. McCarthy had charged that the Department of State knowingly harbored Communists. Hearings on McCarthy’s accusations were held under the chairmanship of Senator Millard Tydings of Maryland. The committee exonerated the State Department. Critics called the proceedings a “whitewash.”

Following McCarthy’s charges, anxiety over domestic Communism intensified. In 1950, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of eleven top leaders of the Communist Party under the Smith Act. The court also refused to review the convictions of two Hollywood writers who had refused to answer questions before a Congressional committee about possible Communist connections. Meanwhile, a Justice Department official, Judith Coplon, was convicted of conspiracy with a Soviet representative at the United Nations (later reversed on procedural grounds), and four people—Harry Gold, David Greenglass, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg—were arrested on charges of atomic espionage.

Around the same time, a grand jury issued indictments for the illegal transfer of hundreds of classified documents from the State Department to the offices of a journal called Amerasia.

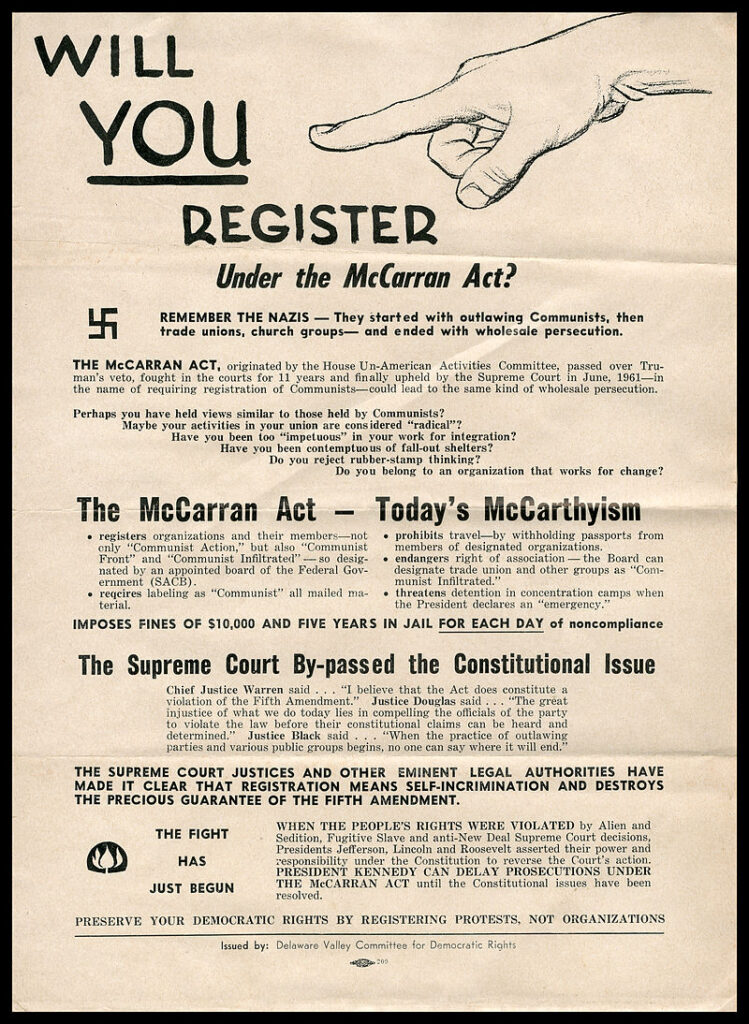

In September 1950, Congress passed the McCarran Act over President Truman’s veto. The act required members of Communist-front organizations to register with a Subversive Activities Control Board. A book by a former U.S. Naval Intelligence officer, Vincent Hartnet, titled Red Channels, made sweeping accusations about Communist influence in the entertainment industry. The book’s charges led the House Un-American Activities Committee to investigate actors, producers, and screenwriters, all of whom were accused of using film, stage, and radio as vehicles for Communist propaganda.

In 1951, the head of the FBI assured Congress that his organization was ready to arrest 14,000 dangerous Communists in the event of war with the Soviet Union. A foundation offered $100,000 to support research in creating a device for detecting traitors.

Domestic Communism

In the 1930s, the Communist Party and associated organizations attracted the support of a glittering array of novelists, screenwriters, critics, and artists. Within the Communist Party, these individuals had found comradeship, acceptance, and a sense of mission.

From its earliest days, the American Communist Party received substantial funding from the Soviet government. In January 1920, the Communist International (or Comintern) supplied the Communist journalist John Reed with approximately $2 million dollars of gold, silver, and jewelry to foster Communism in America. The party also received a constant stream of Soviet political directives that it implemented without question.

In the early 1930s, some 35 states had criminal syndicalism laws — that made it a crime to defend, advocate, or set up an organization committed to the use of violence, sabotage, or other unlawful means to bring about a change — which targeted the American Communist party. Meanwhile, foreign-born Communists (a large proportion of party membership in the 1920s and early 1930s) were in danger of deportation. In a California case, a young woman was sentenced to ten years in prison for raising the Communist banner on a flagpole at a children’s camp.

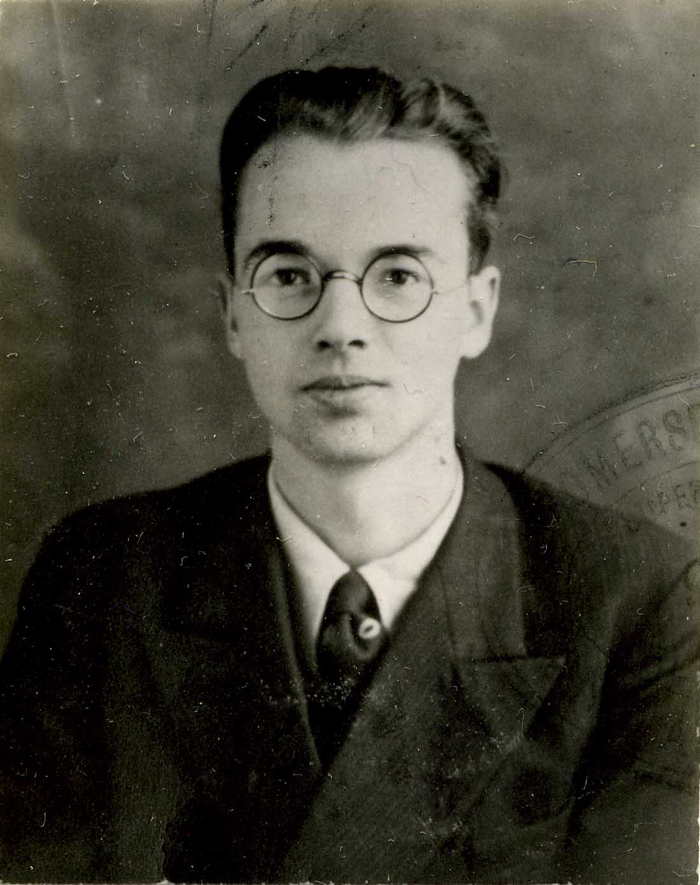

During the 1930s, the U.S. Communist Party’s involvement in espionage was ad hoc, amateurish, and sporadic, and mainly involved pilfered State Department documents. But during World War II, Soviet intelligence agents successfully penetrated the Manhattan Project, the top-secret program to develop an atomic bomb.

Perhaps as many as 300 American Communists were accomplices of Soviet espionage during World War II. From small beginnings in the 1930s, Soviet espionage efforts in the United States increased exponentially during the war years. Pro-Soviet Americans, many of them secret members of the Communist Party working within such sensitive agencies as the State Department, the Treasury Department, and the Office of Strategic Services (the forerunner of the CIA), provided K.G.B. agents with information ranging from well-informed political comments to purloined classified documents. Recently declassified government files indicate that Alger Hiss was involved in passing on government documents; while others, who had been accused of links with the K.G.B., including the head of the Manhattan Project, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and the journalist I.F. Stone, were innocent.

With the end of World War II, the Soviet Union’s most valuable sources within the U.S. government dried up. The defection of Elizabeth Bentley, the notorious “spy queen” who gathered information for transmission to Moscow from dozens of Federal employees, was a critical blow. Some departed under suspicion and pressure.

Spying and Communist Party membership were not identical categories. Of the approximately 50,000 party members in the war years, only about 300 were involved in spying. Some members refused to disclose knowledge when approached for information; others used discretion in the company they kept; while others convinced themselves that the information they leaked was intended chiefly for Communist Party leaders in New York.

Most of the Americans who betrayed their country did not participate because they were blackmailed, needed money, or were psychological misfits; they joined in because of a “romantic anti-fascism” notion—a commitment to such causes as civil rights and improvement in the lives of the working class.

Following the war, support for the Communist Party rapidly declined. In 1956, following the suppression of the Hungarian uprising, three-quarters of U.S. Communists, including many of its most dedicated members, left the party.

The Rosenberg Case

In 1951, in the midst of the Korean war, a federal judge found Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and their associate, Morton Sobell, guilty of having passed atomic secrets to Soviet agents. Ethel Rosenberg’s brother, David Greenglass, had worked at the Los Alamos nuclear research station in New Mexico. The couple was sentenced to death. Judge Irving Kaufman told the Rosenbergs: “I consider your crime worse than murder.”

It now appears likely that Ethel Rosenberg, who was sent to the electric chair in 1953, along with her husband for the crime of atomic espionage, was at most a minor participant in his activities.

Margaret Chase Smith: The Conscience of the Senate

Margaret Chase Smith was the first woman elected to both houses of Congress. She was also the first woman to enter the Senate without being appointed to the position. During World War II, she was the only civilian woman to go to sea in a Navy ship in wartime. She was also the first woman to have her name placed in nomination for president at a major party convention. With only a high school education, she entered politics after her husband, a Republican member of Congress, died. She served four terms in the House and four terms in the Senate.

Smith, known as “the conscience of the Senate,” gained a reputation for courage and independence when she became the first person in Congress to condemn the anti-Communist witch hunt led by Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin. In a fifteen-minute speech on June 1, 1950, barely a year after entering the Senate, she denounced McCarthy for destroying reputations with his reckless charges about Communists and “fellow travelers” in government. She never mentioned the anti-Communist crusader by name; although, no one doubted who she referred to. She told the Senate it was time to stop conducting “character assassination” behind “the shield of congressional immunity.”

Smith then read a “Declaration of Conscience,” signed by six fellow Republicans. “The nation sorely needs a Republican victory,” she declared, “but I don’t want to see the Republican Party ride to political victory on the four horsemen of calumny [misrepresentation]—fear, ignorance, bigotry, and smear.”

McCarthy threatened to destroy her political career. But she was so highly regarded that voters easily re-elected her to the Senate. Many speculated that she would run for president in 1952. Asked what she would do if she woke up in the White House, she replied: “I’d go straight to Mrs. Truman and apologize. And then I’d go home.”

McCarthy Condemned

In 1954, a Senate committee found that Senator McCarthy had wrongfully defied the authority of the Senate, and that he had been abusive of his colleagues (one he had called them “a living miracle, without brains or guts”). After the fall elections of 1954, the Senate voted to condemn McCarthy for conduct unbecoming to his office. The final vote was bipartisan, with 22 Republicans joining 44 Democrats, and 22 Republicans opposed.

Paranoid Style

The film was titled Invasion of the Body Snatcher. Winds carried seed pods into the small California town of Santa Mira. Apparently a result of nuclear tests in the New Mexico desert, the pods had acquired the capacity to gain possession of human bodies. In Santa Mira, the pods began to replace individual townspeople. Children began to notice that adults weren’t themselves and that they lacked emotion. A local doctor investigated only to discover that the police chief and other local dignitaries had become pawns of the invaders.

The film’s themes—infiltration and mind control—reflected some of the preoccupations of the Cold War period. A certain paranoid style, a way of viewing everything in conspiratorial terms, permeated the early Cold War years. It was seen in the rantings of Joe McCarthy and in the tough language of the Truman Doctrine. It was also seen in popular culture.