The Cold War in Developing Countries

The Cold War in Developing Countries

In Europe, there was less violence in the half century following World War II then in almost any previous period of modern European history. Yet outside of Europe and North America, violent conflict became commonplace. In the decades following World War II, many underdeveloped countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America were wracked by civil war, guerrilla movements, and other social conflicts.

Some of these conflicts were traditional wars pitting one nation against another in struggles for territory, natural resources, or national honor; most, however, were conflicts within societies. At first, most of these were struggles to achieve independence from colonial rule. In succeeding years, however, new conflicts pitted various ethnic, economic, and political groups against one another as these groups struggled for power or independence.

Since World War II, American foreign policy makers seriously debated how best to respond to social conflicts within developing societies. In many instances, the United States viewed revolutionary efforts to redistribute land or to overthrow corrupt, repressive governments as part of Soviet attempt to expand Communism throughout the world.

It was in Iran that the United States first responded to the growth of left-wing nationalism.

In 1953, the United States assisted the Iranian military to overthrow the country’s premier, Mohammed Mosaddeq. The premier, a fierce nationalist, called for the expropriation and nationalization of British-run oil fields. Convinced that Mosaddeq had Communist leanings, the CIA helped to organize the coup against the Mosaddeq government. Once Mosaddeq was overthrown and imprisoned, the Shah of Iran was installed as the nation’s ruler, and he subsequently assigned over 40 percent of Iran’s oil fields to U.S. companies.

Guatemala

In 1954, a CIA-backed coup overthrew the elected government of Guatemala, which had nationalized property owned by the United Fruit Company. President Eisenhower’s Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, accused the Guatemalan president of installing “a communist-type reign of terror” and plotting to spread Communism throughout the region. As proof that Guatemala had ties to the Soviet Union, CIA operatives planted Soviet weapons in Guatemala, and CIA pilots bombed airfields in Honduras.

The Guatemalan president had allowed Communists to participate in his government and had instituted a land reform program that had expropriated land owned by the Boston-owned United Fruit Company. The company owned Guatemala’s telephone and telegraph system, its railroad lines, its harbor, and monopolized the banana business.

To undermine the government’s support, the CIA bribed military officers to turn on their commanders and to broadcast combat sounds from the U.S. embassy roof. Finally, it sent American pilots to bomb Guatemalan buildings.

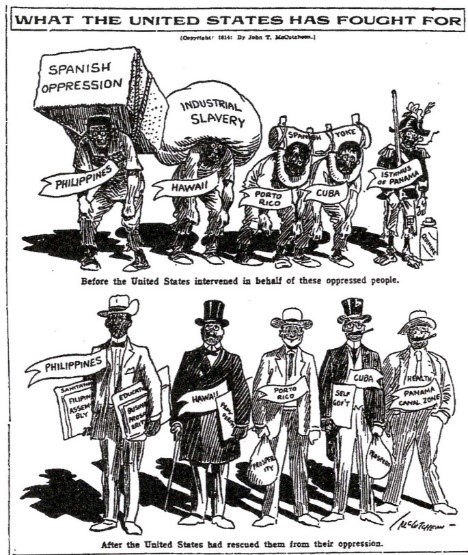

…Political Cartoons: “What the United State Has Fought For”

What does this 1914 cartoon imply is the driving force behind U.S. military interventions overseas?

The Military-Industrial Complex

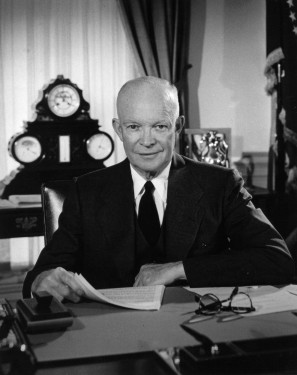

Beginning with George Washington, presidents have used their farewell address to look back on their experience in office and to offer the public practical advice. In his farewell address, President Dwight D. Eisenhower said that a high level of military spending and the establishment of a large arms industry in peacetime were something “new in the American experience.” In the most famous words of his presidency, Eisenhower warned that the country “must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence…by the military-industrial complex.”

President Eisenhower believed that the United States had “to maintain balance” between defense spending and the needs of a healthy economy. During his second term, Congress, the press, and the armed services had pressured Eisenhower to increase defense spending. But even after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first satellite to orbit the earth, he refused to let defense spending unbalance the federal budget. Eisenhower worried that presidents who did not have his military experience would be poor judges of the country’s defense needs.

In his speech, Eisenhower warned that the United States faced a “hostile ideology—global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose,” and must bear “without complaint the burdens of a long and complex struggle.” He also feared that the arms industry, military officers, and members of Congress with military installations and defense plants in their districts, would lead the country to build unnecessary weapons. He worried that the “military-industrial complex” would skew national priorities and dictate the direction of American foreign policy.

The election of a new president, John F. Kennedy, was accompanied by intensified Cold War tensions. During the 1960 presidential campaign, Kennedy spoke of a “missile gap” and claimed that the Soviet Union had achieved an advantage in long-range missiles. In response to Soviet Premier Khrushchev’s pledge to support wars of liberation, Kennedy called for the training of counter-insurgency forces that could combat guerrilla warfare.

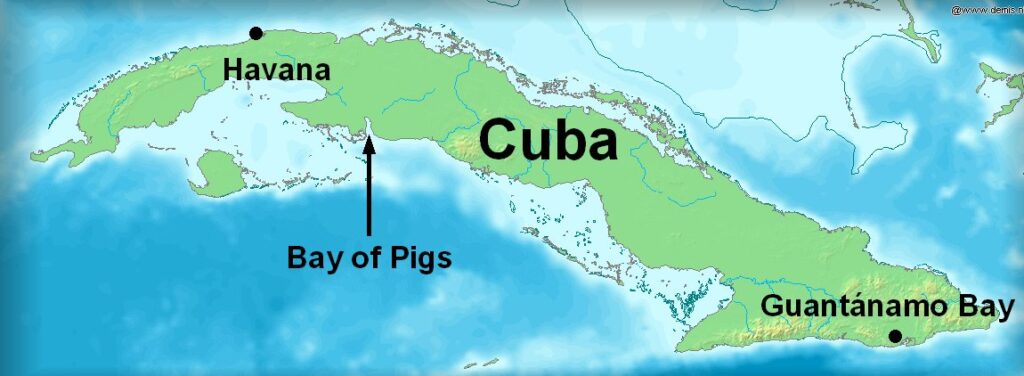

Cuba and the Bay of Pigs Invasion

In 1959, rebel leader Fidel Castro toppled Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. In Washington, Castro told U.S. officials that “The [Cuban] movement is not a Communist movement…. We have no intention of expropriating U.S. property, and any property we take we’ll pay for.”

The next year, the Soviet Union agreed to provide Cuba with $100 million in credit and to purchase five million tons of Cuban sugar. After President Eisenhower declared that the United States would not allow a regime “dominated by international Communism” to exist in the Western hemisphere, Havana nationalized all banks and large commercial industrial enterprises in Cuba. The United States responded by imposing a trade embargo.

In April 1961, a U.S.-sponsored invasion of Cuba led by anti-Castro Cuban émigrés turned into a rout. The members of the invasion force, who had been trained by the CIA in Florida, Louisiana, and Guatemala, were defeated in just three days. On Christmas 1962, the United States traded $53 million worth of medical supplies and food stuff for 1,113 captured invaders and 922 of their relatives.

Even after the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, the United States sought to assassinate Fidel Castro in a series of bizarre plots that involved a contaminated skin-diving suit, a booby-trapped seashell, botulism-laced cigars, a hypodermic needle concealed within a pen, and a poisoned pills. These attempts convinced Cuba and the Soviet Union that the United States would stop at nothing in its efforts to overthrow Cuba’s Communist regime and resulted in a crisis that brought the world to the edge of a nuclear confrontation.

Cuban Missile Crisis

In October 1962, the Soviet Union and the United States went eyeball-to-eyeball and were on the brink of nuclear war.

Surveillance photographs taken by a U-2 spy plane over Cuba revealed that the Soviet Union was installing intermediate-range ballistic missiles. Once operational, in about 10 days, the missiles would need only five minutes to reach Washington, D.C.

President Kennedy decided to impose a naval blockade. Soviet freighters were steaming toward Cuba. The president realized that if the ships were boarded and their cargoes seized, the Soviet Union might regard this as an act of war.

Soviet Premier Khrushchev sent a signal that he might be willing to negotiate. In exchange for the Soviets agreeing to remove the missiles, the United States publicly pledged not to invade Cuba and secretly agreed to remove its aging missiles from Turkey.

After the Cuban Missile Crisis, Cold War tensions eased. In July 1963, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Britain approved a treaty to halt the testing of nuclear weapons in the atmosphere, in outer space, and under water. The following month, the United States and Soviet Union established a hotline providing a direct communication link between the White House and the Kremlin.