Korean War

Korean War

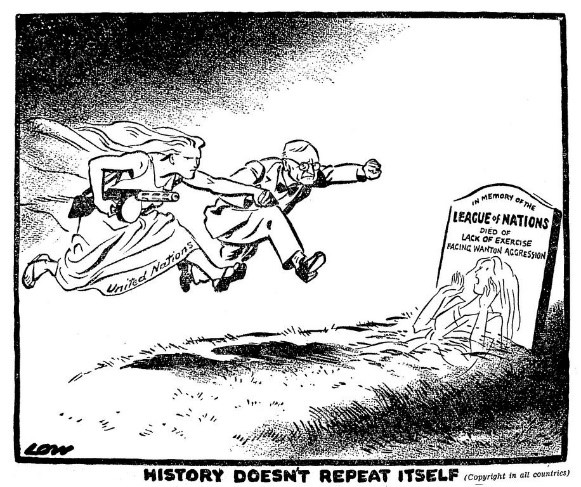

On June 25, 1950, Communist North Korean forces invaded South Korea, beginning a three-year war. It took just three days before the South Korean capital of Seoul fell to the North Koreans. President Truman immediately ordered U.S. air and sea forces to “give the Korean government troops cover and support.” The United States intervened even though it had no formal treaty with South Korea and had earlier implied that the Korean peninsula was outside its sphere of vital national interests.

The Korean War has often been called the “forgotten war,” since it is overshadowed by World War II and the Vietnam War. However, the conflict is anything but insignificant. It cost the lives of 54,246 U.S. soldiers and left 103,284 wounded.It expanded the global role of the United States and set the stage for tensions between North Korea and the United States that persist six decades later.

Korea was a Japanese colony from 1910 to 1945. At the end of World War II, the peninsula was occupied by the Soviet Union in the north and the United States in the south. In 1948, the U.S. backed administration in the south declared itself the Republic of Korea. Shortly later, the Soviet-backed, Communist administration in the north declared itself the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

Each regime denied the legitimacy of the other and both hoped to unify the peninsula under their own terms. The division of the Korean peninsula separated ten million Koreans from their families. Border skirmishes occurred frequently along the 38th parallel, the dividing line between the two nations.

The war pitted South Korea and the United States, fighting under the auspices of the United Nations, against North Korea, which received arms, tanks, and strategic advice from the Soviet Union and China. The conflict was brutal, with an estimated three to four million Koreans killed, over two-thirds of whom were civilians. That amounted to 25 percent of the pre-war Korean population. The South Korean capital, Seoul, changed hands four times during the war.

For three months, the United States was unable to stop the Communist advance. Then, the United States successfully landed two divisions ashore at Inchon, behind enemy lines. The North Koreans fled in disarray across the 38th parallel, the pre-war border between North and South Korea.

The initial mandate that the United States had received from the United Nations called for the restoration of the original border at the 38th parallel. But the South Korean army had no intention of stopping at the pre-war border, and on September 30, 1950, it crossed into the North. The United States pushed an updated mandate through the United Nations, and on October 7, the Eighth Army crossed the border.

By November, U.S. Army and Marine units thought they could end the war in just five more months. China’s Communist leaders threatened to send combat forces into Korea, but the U.S. commander, Douglas MacArthur, thought they were bluffing.

In mid-October, the first of 300,000 Chinese soldiers slipped into North Korea. When U.S. forces began what they expected to be their final assault in late November, they ran into the Chinese army. There was a danger that the U.S. Army might be overrun. The Chinese intervention ended any hope of reunifying Korea by force of arms.

General MacArthur called for the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff to unleash American air and naval power against China. But the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Army General Omar Bradley, said a clash with China would be “the wrong war, in the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy.”

By mid-January 1951, Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway succeeded in halting an American retreat fifty miles south of the 38th parallel. A week and a half later, he had the army attacking northward again. By March, the front settled along the 38th parallel and the South Korean capital of Seoul was back in South Korean hands. American officials informed MacArthur that peace negotiations would be sought.

In April, President Truman relieved MacArthur of his command after the general, in defiance of Truman’s orders, called for the bombing of Chinese military bases in Manchuria. The president feared that such actions would bring the Soviet Union into the conflict and violated the principle of civilian control of military policy.

The Korean War was filled with lessons for the future. First, it demonstrated that the United States was committed to the containment of Communism, not only in Western Europe, but throughout the world. Prior to the outbreak of the Korean War, the Truman administration had indicated that Korea stood outside America’s sphere of vital national interests. Now, it was unclear whether any nation was outside this sphere.

Second, the Korean War proved how difficult it was to achieve victory even under the best circumstances imaginable. In Korea, the United States faced a relatively weak adversary and had strong support from its allies. The United States possessed an almost total monopoly of sophisticated weaponry, and yet, the war dragged on for almost four years.

Third, the Korean War illustrated the difficulty of fighting a limited war. Limited wars are, by definition, fought for limited objectives. They are often unpopular at home because it is difficult to explain precisely what the country is fighting for. The military often complains that it is fighting with one armed tied behind its back. But if one tries to escalate a limited war, a major power, like China, might intervene.

Finally, in Korea U.S. policymakers assumed that they could make the South Korean government do what they wanted. In reality, the situation was often reversed. The South Korean government played a pivotal role in defining military strategy and shaping the peace negotiations. In the end, the United States was only able to extricate itself from the war by making a long-term commitment to the South Korean government in terms of money, men, and materiel.

Today, the Korean peninsula remains one of the most tension-filled areas in the world. North Korea has amassed the fourth largest army in the world and has developed nuclear weapons and missiles capable of delivering these weapons to the U.S. mainland. Meanwhile, the United States has maintained a military presence in South Korea.

Podcast

“Korea—the Right War? At What Price”

Listen to the podcast entitled, “Korea—the Right War? At What Price?,” which can be accessed below.

Transcript “Korea–The Right War? At What Price?”

.. Making Historical Judgements

Between 1945 and 1962 the United States and Soviet Union went from military allies to the verge of nuclear war.

The Death of Stalin and the Cold War

In March 1953, Joseph Stalin, who had ruled the Soviet Union since 1928, died at the age of 73. His feared Minister of Internal Affairs, Lavrenti Pavlovich Beria, was subsequently shot for treason. Nikita Khrushchev then became first Secretary of the Communist Party.

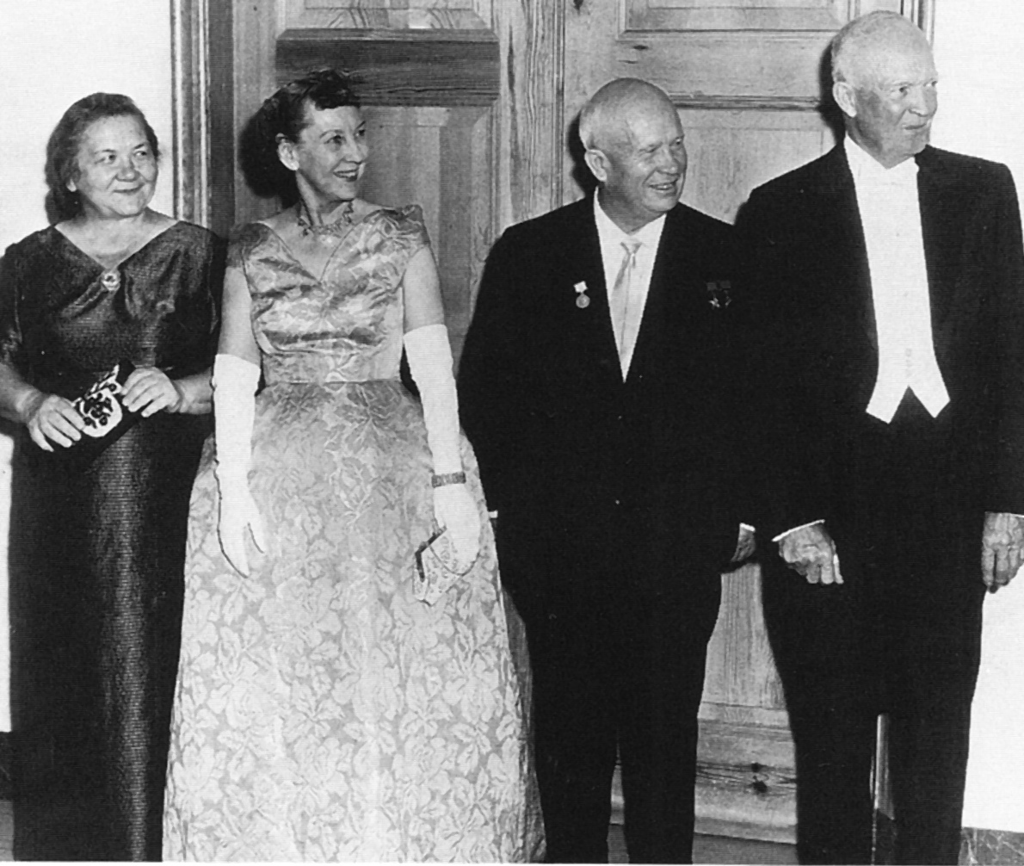

Stalin’s death led to a temporary thaw in Cold War tensions. In 1955, Austria regained its sovereignty and became an independent, neutral nation after the withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country. The next year, Khrushchev denounced Stalin and his policies at the twentieth Communist Party conference. After a summit between President Eisenhower and the new Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Geneva, the Soviets announced plans to reduce its armed forces by more than 600,000 troops. In early 1956, Khrushchev called for “peaceful coexistence” between the East and West.

Relaxation of economic and political controls encouraged Eastern Europeans to demand greater freedom. In 1953, after Communist authorities in East Germany attempted to increase working hours without raising wages, strikes and riots broke out in East Berlin and other cities. Some three million East Germans fled to the West. To halt this mass exodus, in August 1961, East German authorities erected a wall separating East and West Berlin.

In 1956, Polish workers rioted to protest economic conditions under the Communist regime. Poles also demanded removal of Soviet officers from the Polish army. More than a hundred demonstrators were killed as authorities moved to suppress the riots.

In Hungary, university students expressed solidarity with the Polish rebels. More than 100,000 workers and students demanded a democratic government, the withdrawal of Soviet troops, and the release of Jozsef Cardinal Mindszenty, who had been held in solitary confinement since the end of 1948. Sixteen Soviet divisions and 2,000 tanks crushed the Hungarian revolution after Hungary’s Premier Imre Nagy promised Hungarians free elections and an end to one-party rule and denounced the Warsaw Pact. Some 200,000 Hungarians fled the country after the suppression of the uprising.