The Political Crisis of the 1890s

The Political Crisis of the 1890s

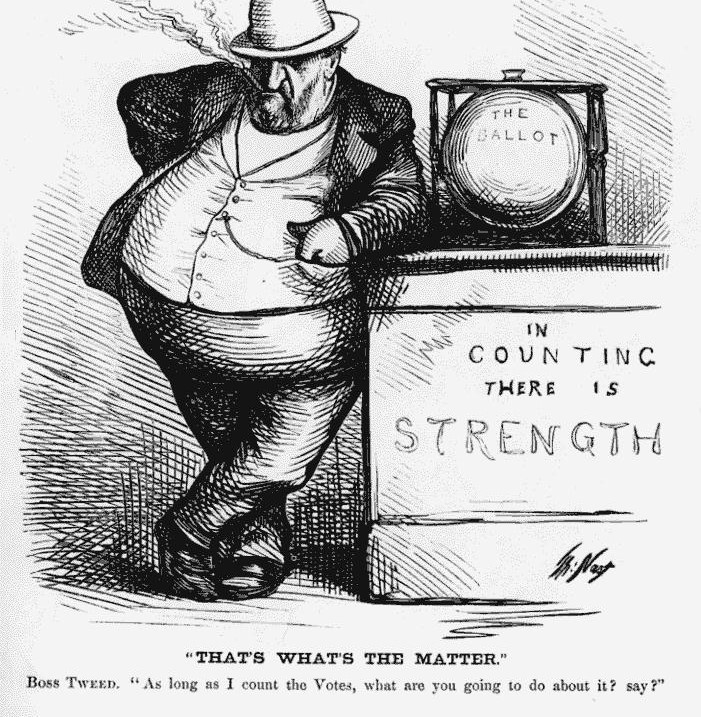

The 1880s and 1890s were years of turbulence. Disputes erupted over labor relations, currency, tariffs, patronage, and railroads The most momentous political conflict of the late nineteenth century was the farmers’ revolt. Drought, plagues of grasshoppers, boll weevils, rising costs, falling prices, and high interest rates made it increasingly difficult to make a living as a farmer. Many farmers blamed railroad owners, grain elevator operators, land monopolists, commodity futures dealers, mortgage companies, merchants, bankers, and manufacturers of farm equipment for their plight. Farmers responded by forming cooperatives to allow them to buy goods at lower prices and get better prices for their crops and organizing Granges, Farmers’ Alliances, and the Populist party and trying to forge an alliance with industrial workers to influence politics. In the election of 1896, the Populists and the Democrats nominated William Jennings Bryan for president. Bryan’s decisive defeat inaugurated a period of Republican ascendancy, in which Republicans controlled the presidency for twenty-four of the next thirty-two years.

In the South, conservative Democrats put down the Populist insurgency of the 1890s by appealing to racial prejudice. Southern Democrats enacted literacy tests and poll taxes not only to disfranchise African Americans, but many poorer whites too.This was a quarter century after the Civil War and more than a dozen years after the end of Reconstruction.

Panacea’s for the Nation’s Ills

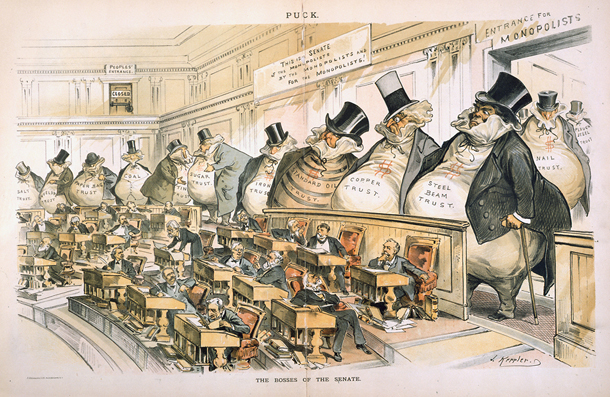

During the late nineteenth century, a growing number of Americans feared that the country’s republican traditions were being steadily eroded by the growth of business monopolies, government corruption, and the violent struggle between capital and labor. In a series of best-selling books, a number of Protestant reformers envisioned a “cooperative society” and proposed cure-all formulas to solve the nation’s social and economic problems.

Henry George’s 1879 book Progress and Poverty, argued that poverty and inequality were the product of the unearned increase in land values and that unemployment and monopolies could be eliminated through the abolition of all taxes except for a single tax on land. Edward Bellamy, in an 1888 bestseller Looking Backward, described an ideal society in the year 2000 in which the government nationalized all resources and takes over all business operations. William Hope Harvey, in Coin’s Financial School, proposed to solve the nation’s economic problems by backing the dollar with silver as well as gold.

At a time when the nation’s problems seemed intractable, books like George’s and Bellamy’s kept alive a faith that the problems of inequality, poverty, and monopoly could be solved. But their books failed to provide practical, realistic steps forward. It would not be until the next era in American history, the Progressive Age, that a new generation of reformers would devise ways for government to improve the quality of American life.

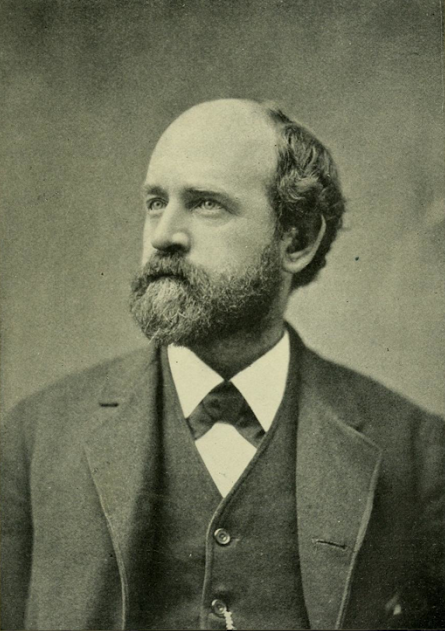

Henry George

Henry George wrote the most influential American economic treatise of the nineteenth century. Entitled Progress and Poverty, and published in 1879, it was translated into 25 languages, outsold Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, and inspired H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw to become Socialists.

Henry George was convinced that all of the society’s ills were rooted in rising land values, which prevented the poor from acquiring property, reduced farmers to tenancy, and discouraged investment. He believed that society was responsible for increases in land value and that it was unfair for landlords alone to profit from this increase. He claimed that a tax on land would penalize those who leave land idle, and would therefore encourage investment and eliminate poverty and unemployment. As he put it:

What I propose, therefore, is the simple yet sovereign remedy, which will raise wages, increase the earnings of capital, extirpate pauperism, abolish poverty, give remunerative employment to whoever wishes it, afford free scope to human powers, lesson crime, elevate morals, and taste, and intelligence, purify government and carry civilization to yet nobler height.

At the age of fourteen, George left his home in Philadelphia and migrated to San Francisco, where he became a successful journalist. Dismayed by the “shocking contrast between monstrous wealth and debasing want,” he wanted to understand the explanation for “advancing poverty with advancing wealth.” He believed that the problem was that wealth was accumulated by landlords rather than those who actually produced wealth. Rather than investing in productive enterprise, the wealthy speculated in land. This was the theme of Progress and Poverty.

After his book brought him international fame, he moved to New York in 1880 and ran for mayor as an independent in 1886. He lost, because he was unable to convince the working class that his scheme would benefit them, but he did finish ahead of Theodore Roosevelt, the Republican candidate. He ran again for mayor in 1897, but died before the election. He was fifty-eight years old.

Although George’s single tax on land was simplistic, his goal was not nonsensical. He wanted to use tax policy to narrow the gap between rich and poor and to encourage productive investment. He was also among the first advocates of urban planning and rational land use policies.

In 1894, twenty-eight people from Iowa moved to Alabama, and established a community founded on George’s ideas. The community’s land was held by the community, who paid only a single tax to cover public services. Today, the community still exists, leasing land to 1,300 farmers, business owners, and homeowners, and remains as a reminder of Henry George’s utopian ideas.

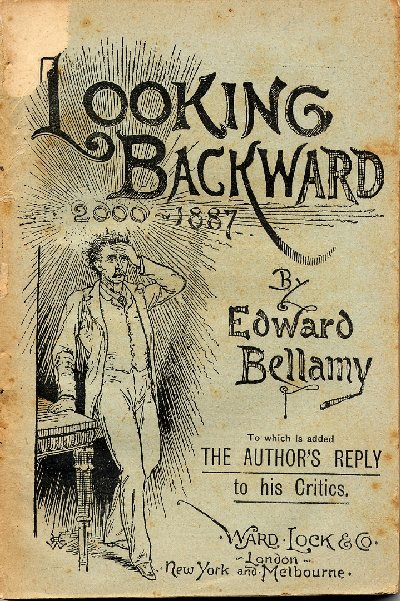

Looking Backward

Only Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben-Hur sold more copies during the nineteenth century. Published in 1888, Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, 2000-1887 sold more than a million copies. When the book appeared, the nation was still suffering from a financial contraction in 1883 and the aftermath of the 1886 Haymarket Square bombing in Chicago.

The book’s main character, Julian West, lives in Boston in 1887, a time of wrenching poverty, labor strikes, and ostentatious wealth. One night, while he is in a hypnotic trance in an underground chamber, his house burns down. His servant, the only person who knows about the underground chamber, dies. He is not awakened until the year 2000. By then, all companies have merged to form one giant trust. Less attractive jobs are made more desirable by shorter hours. At the age of forty-five, all men and women retire.

Politicians and corruption have disappeared. So too have lawyers, since in a society without want or inequality, there is no need for laws. War has also been abolished. A world body regulates international relations and nations’ “joint policy toward the more backward races, which are gradually being educated up to civilized institutions.”

The Atlanta Constitution feared that the novel might bring “a new crusade against property and property rights in general.”

William Hope Harvey

In 1893, William Hope Harvey, a Chicago journalist, published Coin’s Financial School, which sold 400,000 copies within a year. It argued that the gold standard penalized farmers and working people and that backing the dollar with silver as well as gold would solve the nation’s economic problems.

In 1792, Congress had made both gold and silver coins legal tender. In 1873, no provision was made for continuing the silver dollar as legal tender, and Congress declared gold the single unit of value. Falling crop prices and high interest rates led farmers to focus on the elimination of silver as legal tender as the prime reason why money had become so scare. This decision to make gold the sole legal tender was known as “the crime of 1873.”

Using an easy-to-read style, Coin’s Financial School argued that since the world’s gold supply was limited, the amount of money available for investment and loans was restricted. Backing the dollar with silver would expand the currency, cut interest rates, and make investment capital more readily available. But the clash between gold and silver came to symbolize a much deeper conflict—about whether the United States would be a rural and agricultural or an urban and industrial society.

The early and mid-1890s were years of bitter contention. Farmers, who had suffered depressed prices, difficulties in obtaining credit, and high costs in producing and shipping their crops since the 1870s, saw conditions worsen. The depression of 1893 was one of the most severe in the nation’s history. Labor violence broke out in many parts of the country, culminating in 1894 with the Pullman strike that temporarily paralyzed half the nation’s railroads.