The Rise of the Industrial City

The Rise of the City

This section traces the changing nature of the American city in the late nineteenth century, the expansion of cities horizontally and vertically, the problems caused by urban growth, the depiction of cities in art and literature, and the emergence of new forms of urban entertainment.

In the forty years after the Civil War, over twenty four million people flocked to American cities. They came from rural areas in the United States but also across oceans from farming areas and industrial cities in Europe. While the United States’ rural population doubled during these years, the urban population increased more than seven-fold. In 1860, sixteen cities had a population over 50,000 and only nine had a population over 100,000. By 1900, thirty-eight cities had more than 100,000 inhabitants.

The modern American city was not simply a larger version of older towns. In the late nineteenth century, American cities changed dramatically in physical size and spatial layout. In Boston in 1873, the outer boundary of settlement stood just two-and-a-half miles from City Hall. In the 1890s, after the establishment of the electric street railway, the outer border of settlement was six miles away. By annexing surrounding lands and filling in bays, cities grew larger, allowing for greater differentiation in the use of space.

Manufacturing and commerce crowded into city centers. Meanwhile, the development of steam railroad lines in the 1860s, electric-powered streetcars and elevated railways in the 1880s, and electric trolleys in the 1890s allowed the wealthy and the middle class to move along newly constructed trolley and rail lines to the country’s first suburbs. At the same time the urban poor were concentrated in newly constructed tenements, few of which had outside windows. Less than ten percent had indoor plumbing or running water.

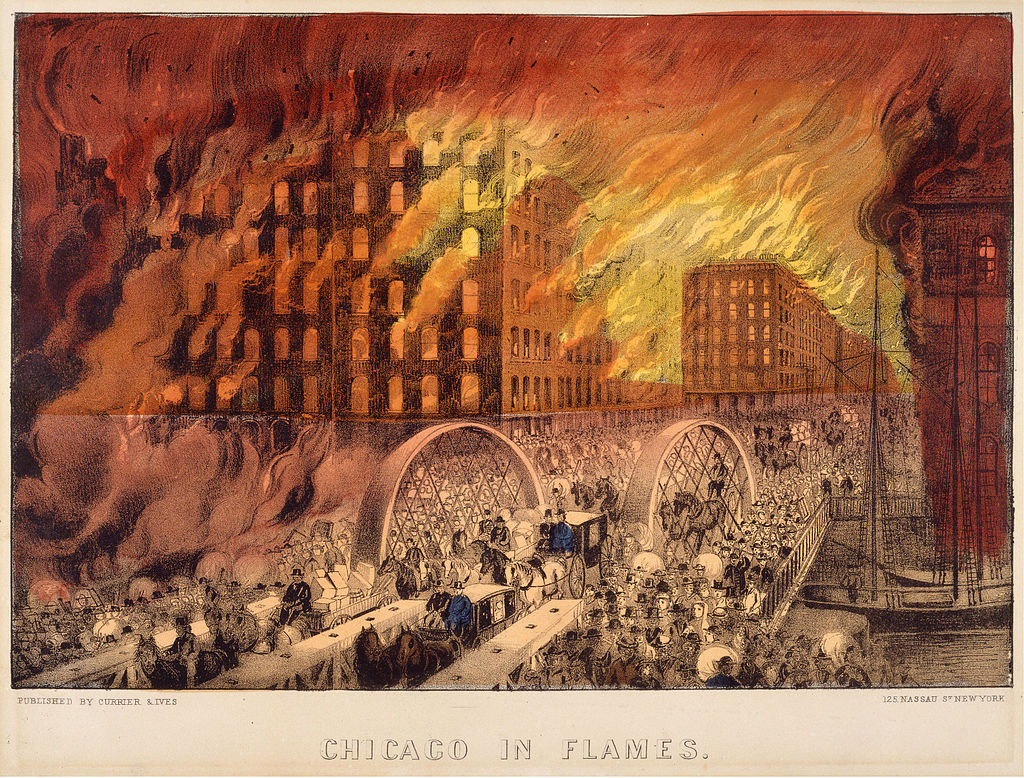

The Great Chicago Fire of 1871

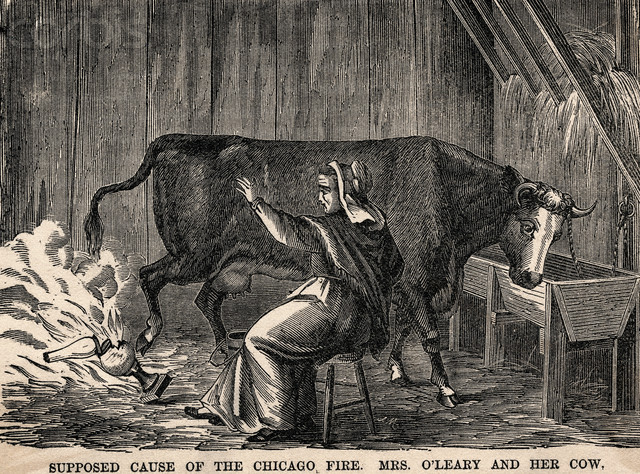

Legend has it that on the evening of October 7, 1871, Mrs. Catherine O’Leary’s cow kicked over a lantern, touching off the Great Chicago Fire. On the drought-stricken evening that the fire started, a thirty-mile-per-hour wind was blowing from the southwest. Fanned to ferocity the blazed scorched its way north and east. Curiously, Mrs. O’Leary’s house was almost untouched. Even the barn where the fire started had only a corner burned out. Today, the Chicago Fire Academy occupies their place.

The fire raged for thirty hours. The blaze, leaping from house to house, ultimately destroyed four-and-a-half square miles of Chicago—some 17,500 buildings. By the time the fire burned itself out on October 10th, the entire business district was destroyed. Six railroad depots and Marshall Field’s department store had gone up in flames. At times, temperatures reached 1,500 to 1,800 degrees. People were incinerated. Limestone disintegrated into powder. Some 250 people were known dead and another 200 were listed as missing and 100,000 people were left homeless.

It seems doubtful that Mrs. O’Leary’s cow actually started the fire. It seems likely that this myth, which was popularized by a 1938 movie In Old Chicago, was the product of anti-Irish, anti-Catholic prejudice. Lyrics about Mrs. O’Leary were written to the tune of “Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight.” Chicago had thousands of wooden buildings and miles of wood-paved streets and sidewalks to burn. There was a months-long drought that year. In 1997, the Chicago City Council passed a resolution officially exonerating Mrs. O’Leary of blame.

Firefighters were exhausted from battling a sixteen-hour fire the previous days. That blaze had injured thirty firefighters. To fight the new fire, Civil War General Philip Sheridan mobilized private citizens. When the fire was finally extinguished, he declared martial law and used guards from the Pinkerton Detective Agency to prevent looting.

The Great Fire overshadowed another huge blaze at the same time. On October 8, 1871, the most devastating forest fire in American history swept through northeast Wisconsin. Apparently, railroad workers clearing land for tracks started a brush fire that soon became an inferno. Peshtigo, Wisconsin, a lumber town not far from Green Bay, was devastated along with sixteen other towns and 1.25 million acres of surrounding forest. Nearly 1,200 people died.

The Skyscraper

Cities grew upward as well as outward. In 1889, the tallest building in the United States was New York’s Trinity Church, near Wall Street. The next year, it was overtaken by the twenty-six-story New York World Building. Fueled by an intense demand for office space in downtown areas, the skyscraper transformed the appearance of American cities.

Brick could not bear the weight of buildings higher than five or six stories. But beginning in Chicago in 1884, steel frame construction allowed architects to design buildings of unprecedented height.

William LeBaron Jenney, a Chicago architect, designed the first skyscraper in 1884. Nine stories high, the Home Life Insurance Building was the first structure whose entire weight, including the exterior walls, was supported on an iron frame. But it would not be for another fourteen years, when the Equitable Life Assurance Building was constructed in Manhattan that a skyscraper contained all the characteristics of a modern skyscraper, including central heating, elevators, and pressurized plumbing.

The arrival of several new technologies permitted the construction of buildings taller than ever before. Foremost among the new technologies was the metal frame, a method pioneered by architect William Jenney in Chicago. Although it was possible to construct buildings more than sixteen stories high using masonry walls, the buildings had to have such thick walls and small windows that they were unappealing to landlords. The falling price of steel during the 1880s meant that tall buildings with steel frames became cheaper to build. The metal skeleton not only supported the roof and floors, but also the external walls. Meanwhile, understanding of fireproofing advanced rapidly after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and construction of the Eiffel Tower in 1889 taught architects how to brace a metal frame against the winds.

To transport people within the building, skyscraper needed elevators. During the 1870s, some five and six story buildings had steam-powered elevators, which had cables wound around a huge rotating drum; but these were not suitable for taller buildings, since the drum would have to be impractically large. The Eiffel Tower used hydraulic-powered elevators, which required a huge power source. During the 1880s, the electric elevator offered a more practical solution.

Tall buildings also needed ventilation systems to heat them in the winter and cool them in the summer. The early ventilation systems, introduced in the 1860s, used steam-powered fans to move air through ducts. After 1890, fans were driven by electricity. Steam heating using radiators was widely used by 1885. Plumbing to circulate water through the building relied on pressure from electric pumps.

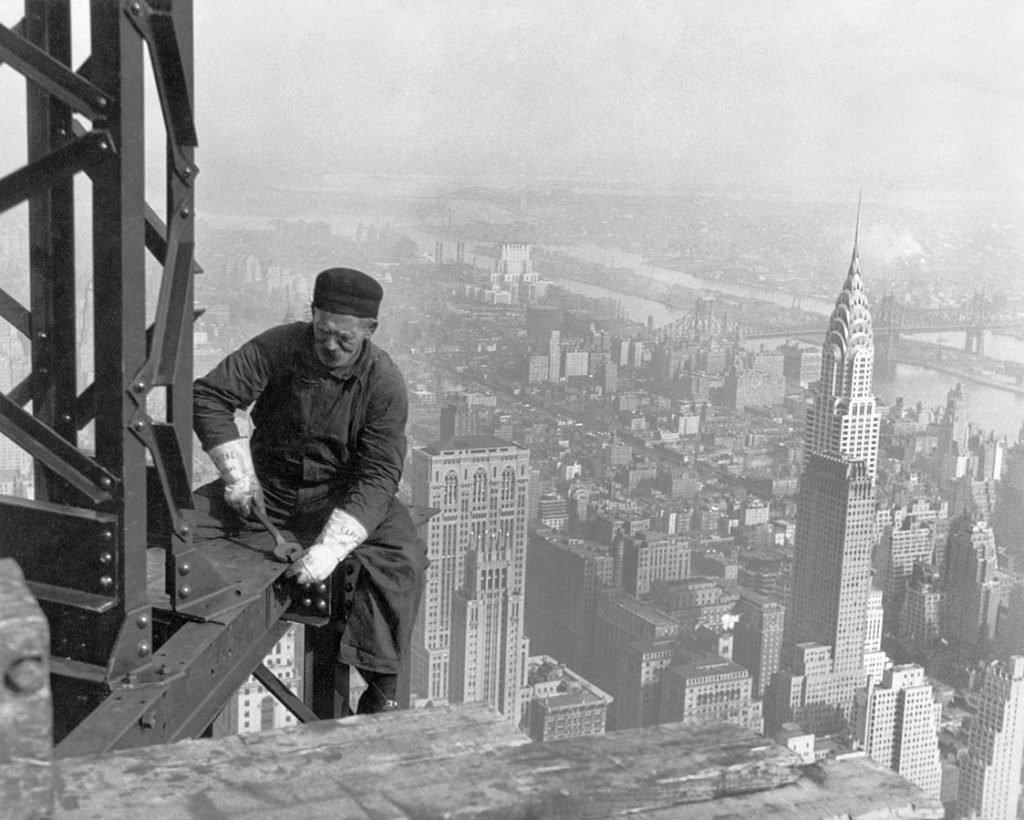

The early twentieth century skyscraper culminated with New York City’s Empire State Building formally opened on May 1, 1931. President Herbert Hoover and New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt attended the dedication of the 102-story, 1,250 foot high building. Erected in just thirteen months, the building grew at a rate of more than a story a day, while constructed workers toiled on girders a fifth of a mile above the ground. The building would remain the world’s tallest for forty years, before it was overtaken by the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Center.

When the Empire State Building opened in the midst of the Depression, only twenty-eight percent of the office space was rented. Revenue generated by thousands of visitors who stood on the building’s observation deck helped keep the building from going bankrupt. A symbol of the modern city, the Empire State Building was where King Kong made his last stand in the 1931 movie.

Tenements

The immigrant poor lived in overcrowded, unsanitary, and unsafe housing. Many lived in tenements, dumbbell-shaped brick apartment buildings, four to six stories in height. In 1900, two-thirds of Manhattan’s residents lived in tenements.

In one New York tenement, up to eighteen people lived in each apartment. Each apartment had a wood-burning stove and a concrete bathtub in the kitchen, which, when covered with planks, served as a dining table. Before 1901, residents used rear-yard outhouses. Afterward, two common toilets were installed on each floor. In the summer, children sometimes slept on the fire escape. Tenants typically paid ten dollars a month rent.

In tenements, many apartments were dark and airless because interior windows faced narrow light shafts, if there were interior windows at all. With a series of newspaper articles and then a book, entitled How the Other Half Lives, published in 1889, Jacob Riis turned tenement reform into a crusade.