Migration as a Theme in U.S. History

Migration as a Key Theme in U.S. and World History

The massive movement of peoples as a result of voluntary choice, forced removal, and economic and cultural dislocation has been one of the most important forces for social change over the past 500 years. Changes produced by migration—such as urbanization or expansion into frontier regions—transformed the face of the modern world. Migration has also played a pivotal role in the formation of modern American culture. The United States has the most diverse population in the world. Our most cherished values as well as our art, literature, music, technology, and cultural beliefs and practices have been shaped by an intricate process of cultural contact and interaction. Because ours is a nation of immigrants, drawn from every part of the world, the study of migration provides a way to recognize and celebrate the richness of our population’s ancestral cultures.

Historical understanding demands more than a solid grasp of historical events and personalities. It also requires students to understand basic historical and sociological terms and concepts. The following skills-building exercises are designed to increase understanding of the complexity of migration.

Kinds of Migrants

When we think of migrants, one image quickly comes to mind: people who permanently depart their place of birth and travel hundreds and even thousands of miles to make a new home. But this kind of migration represents only one of many forms of migration.

Migration may be voluntary or involuntary. Involuntary migrants are those people who are forced to move—by organized persecution or government pressure. Migration may be temporary or permanent. Approximately a third of the European immigrants who arrived in the United States between 1820 and World War I eventually returned to live in their country of origin. These “birds of passage,” as they are known, often returned to the United States several times before permanently settling in their homeland.

Migration may also be short distance or long distance. Short-distance migrants might move from a rural community to a nearby urban area or from a smaller city to a larger one. Migration may be cyclical and repetitive, like the rhythmic migrations of nomadic livestock herders or present day farm laborers. Or it may be tied to a particular stage in the life cycle, like the decision of an adolescent to leave home to go to college.

The motives behind migration may also vary widely. Migration may occur in reaction to poverty, unemployment, overcrowding, persecution, or dislocation. It may also arise in response to employment opportunities or the prospects of religious or political freedom. In distinguishing between different kinds of migration, it is important to look at:

- The distance traveled;

- The causes of migration;

- Whether migration is temporary, semi-permanent, or permanent;

- Whether the migration is voluntary, involuntary, or the result of pressure.

Questions to think about:

- Do you think that temporary migrants are less likely to learn the language of their new place of residence or to marry individuals outside their ethnic group?

- Do you think they are more or less likely to establish community, culture, labor, or religious organizations in their land of residence?

- Do you think that temporary migrants are more likely to select jobs that allow them to be mobile?

History Through…

…Language of Cultural Mixture and Persistence

The study of migration encourages us to think about the process of cultural adjustment and adaptation that takes place after migrants move from one environment to another. In the early twentieth century, Americans commonly thought of migration in terms of a “melting pot,” in which immigrants shed their native culture and assimilated into the dominant culture. Today, we are more likely to speak of the persistence and blending of cultural values and practices.

Assimilation: Absorption into the cultural tradition of another group.

Creolization: Cultural patterns and practices that reflect a mixture of cultural influences. In terms of language, creolization refers to the way that a subordinate group incorporates elements of a dominant group’s language, simplifying grammar and mixing each groups’ vocabulary.

Fusion: The melding together of various cultural practices.

Hybridization: A fusion of diverse cultures or traditions.

Redefinition: To alter the meaning of an existing cultural practice, tradition, or concept.

Survival: The persistence of an earlier cultural practice in a new setting.

Syncretization: The way that a group of people adapts to a changing social environment by selectively incorporating the beliefs or practices of a dominant group.

History Through…

…Music and Migration

As they traveled from one environment to another, immigrant groups carried their musical traditions with them. These musical traditions included ceremonial music, folk music, work songs, dance music, instrumental music, and popular songs as well as distinctive forms of musical instrumentation.

The New World slaves, for example, created the banjo in the New World, modeled on earlier African musical instruments. West Africa had one of the most complex rhythmic cultures in the world, and in developing musical forms in the New World, African Americans made extensive use of rhythmic syncopation. This musical term refers to temporarily breaking the regular beat in a piece of music by stressing the weak beat and singing and embellishing around the beat. African Americans drew upon these earlier traditions to create music as diverse as the Spiritual (which blended together rhythmic and melodic gestures drawn from African music with white church music), Ragtime (which combined a syncopated melodic line with rhythms drawn from musical marches), the Blues (songs of lamentation which made extensive use of ambiguities of pitch), and Jazz (an improvisational form of music that represents an amalgam of blues, ragtime, and Broadway musical forms).

Migration resulted in the creation of new musical hybrids, styles, and genres. The polka, a popular dance of the mid-nineteenth century, represented an American adaptation of German tradition.

One of the earliest forms of commercial popular music was the minstrel song, which accompanied a popular form of nineteenth century theatrical entertainment. Minstrel songs represented an adaptation of earlier ethnic and popular musical traditions. The minstrel song—typified by Stephen Foster’s Old Folk’s at Home and his Camptown Race Track—drew its rhythm partly from the polka and its spicy syncopation from African and African American music. Minstrel songs, many performed by performers in blackface that we find particularly offensive, included both fast-paced dance music and slow-paced, sentimental ballads.

In Latin America, the music of various ethnic groups blended together to form musical and dance forms that would become recognizable worldwide. Spanish, African, and various Indian musical traditions combined in intricate ways to form the tango, the cha-cha, the mamba, the rumba, and reggae.

Language and Migration

As people move from one environment to another, they carry their language with them. What happens to their language as a result of migration?

Some groups of migrants maintain a distinctive language over many generations. For the Quebecois in Canada, the French language has served as an important emblem of identity. Similarly, for many European Jews, Yiddish (for Ashkenazi Jews) and Ladino (for Sephardic Jews) offered an instrument that allowed Jews in diverse countries to easily communicate. In some cases, an immigrant group is able to preserve forms of speech largely intact over hundreds of years. Thus, some inhabitants of the Appalachian Mountain region of the United States speak forms of English that closely resemble seventeenth century English. Somewhat similarly, in the sea islands off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, a distinctive Gullah language that combines elements of English and West African languages continues to thrive.

Over time, many migrants adopt the language of their new homeland. But even when migrants shed their native tongue, terms derived from the earlier language often persist. Many slaves in the United States, for example, selected English names that resembled African names or which followed the West or Central African practice of naming children after an event or a particular day of the week. African names with English phonetic and semantic equivalents were particularly likely to persist. Thus Quacko (meaning Wednesday) became Jack; Cudjoe (Monday) became Joe; and Phiba (Friday) became Phoebe.

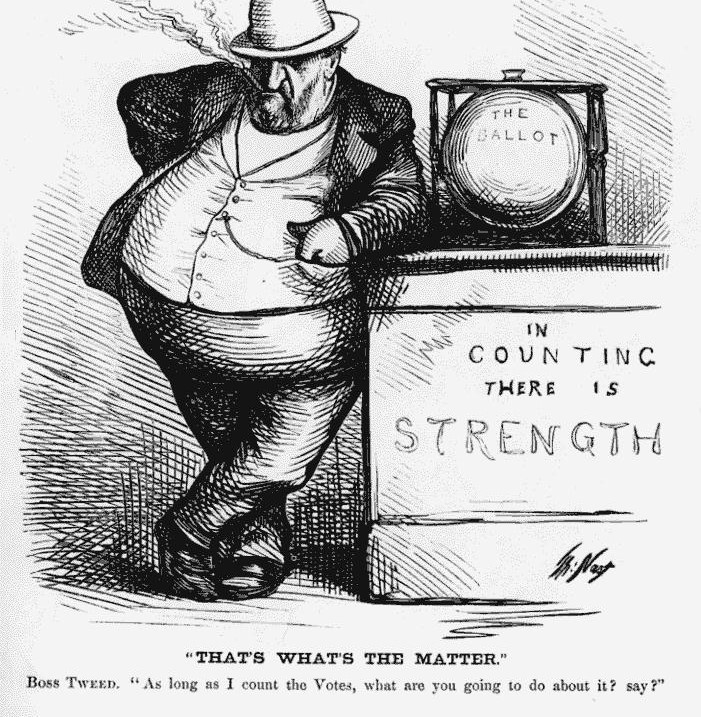

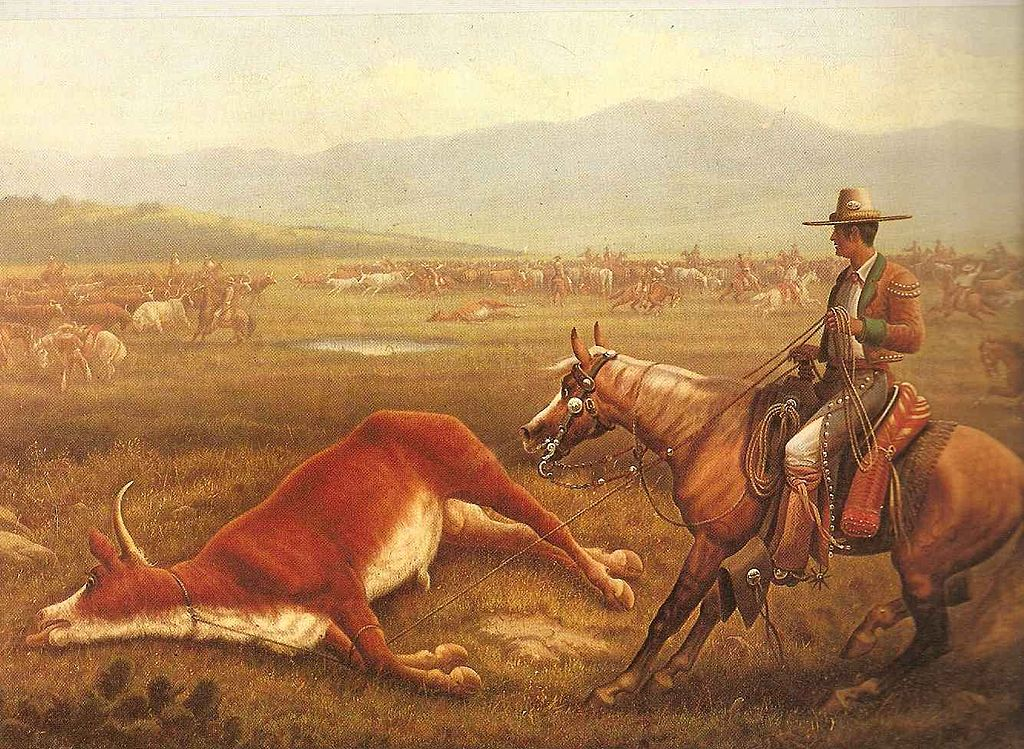

It is very common for words derived from one group of people to be absorbed or adopted by the “mainstream” or “dominant” culture. Thus, cowboys of the Southwestern United States adopted the language (as well as the clothing styles) of Mexican vaqueros, including such words as barbeque, chaps, lasso, ranch (from rancho), and rodeo.

Even when words derived from an earlier language disappear, forms of grammar, syntax, and sentence structure sometimes persist.

Movies and Migration

Many of our most memorable images of the past come from movies. Films set in the past provide a vivid record of history: of the “look,” the clothing, the atmosphere, and the mood of past eras. Nevertheless, movies remain a controversial source of historical evidence. Because moviemakers are not held to the same standards as historians, historical films often contain inaccuracies and anachronisms. Further, films frequently blur the line between fact and fiction and avoid complex ideas that cannot be presented visually.

Of course, no one goes to a movie expecting a history lesson. Feature films are a form of art and entertainment, and screenwriters frequently take license with historical facts in order to enhance a movie’s appeal and drama. Feature films rely on a variety of techniques that tend to distort historical realities. For one thing, popular films tend to be formulaic; they draw upon a series of conventions, stereotypes, and stock characters to tell a story. Also, films tend to “personalize” history by using individual characters to illustrate larger social processes and conflicts.

Still, if analyzed critically, films can provide a valuable window onto the past. History is not simply an accumulation of objective facts; it is also an attempt to interpret facts. Like a novel, a film can offer an interpretation of the past. Indeed, filmmakers’ freedom can give them an opportunity to explore issues of character and psychology that historians sometimes avoid.

Immigration has long been a popular cinematic theme. The birth of film coincided with an unprecedented wave of global immigration. Immigrants formed a large share of film’s early audience, and many early films, including the first “talkie,” The Jazz Singer, dramatized and personalized the immigrant experience.

Carlos E. Cortés (in Robert Brent Toplin, ed., Hollywood as Mirror (Westport, Connectifcut: Greenwood Press, 1993), argues that Hollywood films offer a great deal of valuable information on the subject of immigration. Silent movies, for example, can provide clues about popular attitudes toward immigrants, about immigrants’ aspirations, and about the obstacles immigrants encountered as they sought to enter new societies. In addition, silent films provide vivid glimpses of ethnic neighborhoods and enclaves. A number of films released during World War I address the issue of national loyalty. They ask whether immigrants would remain loyal to their place of birth or identify with their new homeland.

During the 1920s, many popular films emphasized themes of assimilation and acculturation. Such films as Abie’s Irish Rose (1929) celebrated ethnic intermarriage as a vehicle of assimilation, while other popular films, such as The Jazz Singer (1927), praise characters who overcome the pressure to maintain ethnic or religious traditions or refuse to follow their father’s vocation.

During the Great Depression’s earliest years, when the conventional ladder of success seemed to have broken down, many films looked at crime as a vehicle for upward mobility. The popular urban gangster film typically focused on the struggle of young ethnic of Chinese, Irish, or Italian descent to overcome a deprived environment and achieve wealth and power. Later in the Depression, many popular films celebrated immigrants’ efforts to enter mainstream society and achieve material success through a combination of optimism and hard work. World War II combat films portrayed the military as an ethnic melting pot where men of diverse ethnic backgrounds melded together to form an effective fighting unit.

The early post-war era saw a proliferation of “social problem” films that emphasized the problems of poverty, prejudice, and discrimination immigrants faced as they entered a new society. The late 1960s and 1970s witnessed a host of popular films that explored Italian and Jewish ethnic groups’ immigrant roots, sometimes nostalgically, as in Hester Street (1975), and sometimes critically, as in The Godfather (1972).

Popular film’s interest in migration persists. In recent years, many films have examined the plight of undocumented immigrants, economic competition among ethnic groups, problems of cultural and linguistic adjustment, and the generation gap among immigrants and their children.

Why Do People Migrate?

In trying to understand why people migrate, some scholars emphasize individual decision-making, while others stress broader structural forces. Many early scholars of migration emphasized the importance of “push” and “pull” factors. According to this viewpoint, people decide to leave their homeland when conditions there are no longer satisfactory and when conditions in another area are more attractive.

In recent years, many scholars have argued that a thorough understanding of the decision to migrate involves looking at various levels of explanation: the individual, the familial and the structural-institutional. The first level of explanation—the individual or the psychological—focuses on individual perception and asks what advantages individuals hope to obtain by migrating. These often include the prospects of increased economic opportunity or a higher standard of living or escape from social turmoil.

A second level of explanation focuses on family needs. Often, the decision to migrate is not simply a personal but a family decision, reflecting the desire of a larger family unit to enhance its security or improve its well-being. Many family or kin groups receive “remittances”—cash payments that help to support family members—from relatives who have migrated to another area.

A third level of explanation—the structural and institutional—focuses on the broad social, political and economic contexts that encourage or discourage population movement. Factors that stimulate migration include improvements in transportation and communication or income differentials between more economically advanced and less advanced areas. War, too, often induces migration. Factors that inhibit migration include immigration laws restricting exit or entry or laws or social practices that tie farmers to the land (such as sharecropping or debt peonage which prevented many African Americans from leaving the post-Civil War American South).

Push Factors: Factors that repel migrants from their country of origin—include economic dislocation, population pressures, religious persecution, or denial of political rights.

Pull Factors: Factors that attract migrants to move, including the attraction of higher wages, job opportunities, and political or religious liberty.

Uneven Development: Disparities in income, standards of living, and the availability of jobs within and across societies.

Who Migrates?

Even in societies with high rates of emigration, not everyone migrates. Who chooses to stay and who goes?

Migrants are rarely a random cross-section of the population. Rather, migrants usually share certain social characteristics, including age, sex, marital status, occupation, and ethnic background. Thus, for example, many early twentieth century Italian migrants were unmarried men in their teens or twenties; most early-twentieth century Russian migrants were Jews.

Migration often takes place during a particular stage of the life cycle. It is particularly common for individuals to migrate during adolescence or early adulthood or at the time of marriage.

Many studies of migration have emphasized the idea that migrants have a different psychology than those who decide to remain behind. Some speculate that migrants are less tradition-bound, more restless, or more aspiring than non-migrants. Many scholars distinguish between the true “innovators,” the first individuals in a particular society to migrate to a new area, and those who follow in their footsteps.

In some instances, it seems clear that migrants are traditionalists who seek to preserve an older way of life. During the mid-nineteenth century, many German emigrants to the United States were motivated by a desire to maintain pre-industrial crafts in the face of disruptive social and economic changes linked to the rise of industry. Many migrated to rural areas in the U.S. Midwest, where they set up farms or engaged in crafts.

What, then, are the effects of migration on their community of origin? Migration often entails the loss of people with certain characteristics—age, sex, social attitudes, education, religion, ethnicity, and income. Because migrants often consist of a disproportionate number of young men, migration tends to reduce a community’s population growth rate. Recently, many economically underdeveloped societies have expressed a fear that migration has resulted in a “brain drain”—a loss of the society’s most educated and highly skilled members—to wealthier countries.

Innovators: The first individuals in a society to migrate to a new area.

Traditionalists: Immigrants who seek to preserve an earlier way of life.

The United States’ Changing Face

Today, immigration to the United States is at its highest level since the early twentieth century. Some ten million legal and undocumented immigrants entered the country during the 1980s, exceeding the previous high of nine million between 1900 and 1910.

Shaped by an unprecedented wave of immigrants from Latin America, Asia and Africa, the face of the United States has changed in the space of twenty years. In 1996, nearly one in ten U.S. residents was born in another country, twice as many as in 1970. Since 1965, when the United States ended strict national immigration quotas, the number of Hispanics in the United States tripled and the number of Asians increased nearly eight-fold.

As recently as the 1950s, two-thirds of all immigrants to the United States came from Europe or Canada. Today, more than eighty percent are Latin American or Asian. The chief sources of immigrants are Mexico, the Philippines, China, Cuba, and India. Nearly half of the foreign-born population is Hispanic; a fifth is Asian; a twelfth is black.

As a result of massive immigration, the United States is becoming the first truly multi-racial advanced industrial society in which every resident will be a member of a minority group. California recently became the first state in which no single ethnic group or race makes up half of the population.

Immigration’s impact has been geographically uneven, concentrated in distinct parts of the country. Immigrants have been attracted to areas of high growth and high rates of historic immigration. Immigrants are particularly attracted to areas where their countrymen already are. Three-quarters of all immigrants live in six states—California, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, and Texas—and more than half of these migrants settled in just eight metropolitan areas.

Meanwhile, the native-born population is itself on the move. For every ten immigrants who arrive in the nation’s largest cities, nine native-born inhabitants leave for a residence elsewhere. Because most of those leaving metropolitan areas are non-Hispanic whites, the United States population has grown more geographically divided even as it becomes more ethnically diverse.

As in the past, the South remains the region with the fewest foreign immigrants. But it is experiencing a rapid influx of native-born migrants—black and white. Reversing the great northward migration of the early and mid-twentieth century, a significant number of African Americans are abandoning northern industrial cities and are returning to big cities in the South.

Work has always been the great magnet attracting migrants to the United States. Historically, immigrants tackled jobs that native-born Americans avoided, such as digging canals, building railroads, or working in steel mills and garment factories. Today, many immigrants help meet needs for highly skilled professionals, while other less-educated immigrants find employment as maids, janitors, farm workers, and poorly paid, non-unionized employees.

Each wave of immigrants has also sparked a wave of anti-immigrant sentiment. Since the first wave of mass immigration from Germany and Ireland in the 1840s, nativists have expressed fear that immigrants depress wages, displace workers, and threaten the nation’s cultural values and security.

Even though the United States conceives of itself as a refuge for the poor and tempest-tossed, it is also a society that has experienced periodic episodes of intense anti-immigrant fervor, particularly in times of economic and political uncertainty. Unlike nineteenth century nativists who charged that Catholic immigrants were subservient to a foreign leader, the Pope, or later xenophobes who accused immigrants of carrying subversive ideologies, today’s immigration critics are more concerned about immigration’s effects on the country’s economic well-being.

Many fear that newcomers make use of services like welfare or unemployment benefits more frequently than natives. Others argue that the new wave of immigrants is less skilled than its predecessors and is therefore more likely to become a burden on the government. Many worry that the society is being split into separate and unequal societies divided by skin color, ethnic background, language, and culture. Fear that immigrants are attracted to the United States by welfare benefits, led Congress in 1996 to restrict non-citizens’ access to social services.

Census data present a complicated picture of today’s immigrants. They show that many immigrants are better educated than the native born, while others are less educated. Today, about twelve percent of immigrants over the age of twenty-five have graduate degrees, compared with eight percent of the native born. Yet thirty-six percent have not graduated from high school, compared with seventeen percent of the native born. Some immigrants have found employment as highly skilled engineers, mathematicians, and scientists; but about a third of immigrants live in poverty. On average they earn about $8,000 a year, compared with native-born average of nearly $16,000.

Yet if some Americans express anxiety about immigration, others are hopeful that increasing population diversity will teach Americans to tolerate and even cherish the extraordinary variety of their country’s people.

Evaluating the Economic Costs and Benefits of Immigration

Few subjects arouse more controversy than the economic impact of immigration. Some argue that migration benefits societies economically by providing a pool of young, energetic, reliable workers. Others argue, in contrast, that immigration overload the labor force, overburdens social services, and overwhelm society’s capacity to absorb and assimilate newcomers.

Critics of immigration make several economic arguments. They contend that immigrants take jobs away from low-skilled native born workers and depress wages. They maintain that immigrants make greater use of public services such as welfare, health services, and public education than do the native born. They also argue that the immigrants who are currently arriving into countries such as Canada, France, Germany, and the United States are relatively less-skilled and less-educated than those who came in the past, and that they are more cut off from mainstream culture than those who arrived earlier in history. Such critics argue that restricting immigration would open up job opportunities for many native-born minority workers and reduce tax burdens.

Proponents of immigration respond to such arguments in several ways. For one thing, they argue that in evaluating the costs and benefits of immigration, it is important to recognize the ways that immigrants contribute to living standards, particularly for the middle class. Although low-wage immigrant workers are often blamed for unemployment and depressed wages, in fact they make it cheaper to buy many goods and services—everything from fresh fruit and vegetables to clothing, construction, and childcare. As birth rates fall, immigrants assume many necessary but less desirable jobs, picking crops, washing dishes in restaurants, laundering clothes, staffing hospitals, and running small shops.

Undocumented (or “illegal”) immigrants, they maintain, are overwhelmingly employed in sectors of the economy paying low wages, offering little job security, and few or no benefits. Because of the lack of opportunities for advancement, few native-born workers are attracted to these jobs.

Proponents of immigration further argue that immigrants are not simply producers, but consumers as well, who create demand that helps invigorate an economy. They create markets for housing, clothing, and other products and services. In general, immigrants are attracted to areas of high economic growth and labor shortages and as a result they note that immigration has little or no effect on the wages or unemployment rate.

Questions to think about:

- How do you evaluate these contrasting points of view?

- What kinds of evidence in support of these positions would you find most persuasive?