The Huddled Masses

The Huddled Masses

Around the turn of the twentieth century, mass immigration from eastern and southern Europe dramatically altered the population’s ethnic and religious composition. Unlike earlier immigrants, who had come from Britain, Canada, Germany, Ireland, and Scandinavia, the “new immigrants” came increasingly from Hungary, Italy, Poland, and Russia. The newcomers were often Catholic or Jewish and two-thirds of them settled in cities. In this section, you will learn about the new immigrants and the anti-immigrant reaction.

The Statue of Liberty

It is the tallest metal statue ever constructed, and, at the time it was completed, the tallest building in New York, twenty-two stories high. It stands 151 feet high and weighs 225 tons. Its arms are forty-two feet long and its torch is twenty-one feet in length. Its index fingers are eight feet long and it has a four-foot six-inch nose. For people all around the world, the statue symbolizes American freedom, hope, and opportunity.

There may be grander monuments, but this statute was not like the Egyptian pyramids or the Colossus of Rhodes, “the brazen statue of Greek fame.”

The statue was originally proposed by a now obscure French historian, Edouard de Laboulaye, a prominent French abolitionist, and designed by the French sculptor Frederic Auguste Bartholdi. The statue was intended to commemorate the abolition of slavery; symbolically, the statue has severed chains on one of her feet.

The Statue of Liberty was a gift from French Republicans who wanted to advance their political cause: the replacement of the monarchy of Napoleon III with a republican system of government. It was modeled, in part, on the Roman goddess Libertas, the personification of liberty and freedom in classical Rome, which led some critics to object to a heathen goddess standing in New York harbor. Others derided the statue as a “useless gift,” “Neither an object of Art or of Beauty,” and it seemed possible that the statue would be placed in Boston or Philadelphia.

The final $100,000 for the statue’s pedestal were raised by the Hungarian-born publisher Joseph Pulitzer, who asked New York’s poor for contributions. In exchange, he printed their names in his newspaper. One wrote a letter to his paper, The World: “I am a young girl alone in the world, and earning my own living. Enclosed please find sixty cents, the result of self-denial. I wish I could make it sixty thousand dollars, instead of cents, but drops make the ocean.”

Over time, the statue’s symbolic meaning has been transformed. It was originally intended to express opposition to slavery. After the America’s emergence as a world power after its defeat of Spain in the Spanish-American War of 1898, the statue became a symbol of American might. It was not until the twentieth century and massive immigration from eastern and southern Europe that the statue became “a lady of hope” for immigrants and refugees.

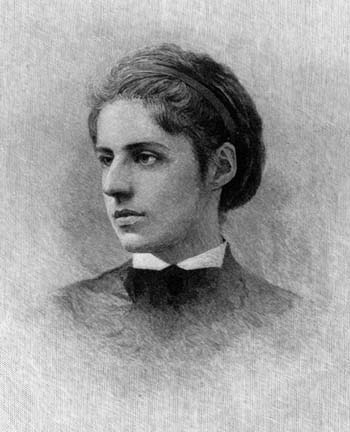

Emma Lazarus

On a tablet on the pedestal of the statue of liberty is inscribed a poem. Entitled “The New Colossus,” it contains the famous words, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

These words were not originally attached to the statue. The poem, which was written in 1883 to help raise money for the statue’s pedestal, was forgotten until it was rediscovered in a Manhattan used-book store. The text was only placed on the pedestal in 1903, and it transformed the statue’s meaning.

Its author, Emma Lazarus, was an American Jew, born in New York City in 1849. She had a privileged upbringing, and wrote a volume of poetry that was privately printed by her father.

In 1881, a wave of anti-Semitism swept across Russia. Soldiers destroyed Jewish districts, burning homes and synagogues. Thousands of Jews set sail for America. Lazarus was shocked by what she saw and devoted herself to helping the refugees.

The final sum needed to complete the pedestal came from an auction of literary works by such authors as Mark Twain and Walt Whitman. Emma Lazarus was asked to contribute a poem. She was reminded of the Colossus of Rhodes, a huge bronze statue of the sun god Helios, one of the wonders of the ancient world. She called her poem “The New Colossus,” and it was sold for $1,500. At the time, she was dying of cancer. She was just thirty-eight years old when she died in 1887.

The New Immigrants

Some 334,203 immigrants arrived in the United States in 1886, the year of the statue’s dedication. A Cuban revolutionary, Jose Marti, wrote: “Irishmen, Poles, Italians, Czechs, Germans freed from tyranny or want—all hail the monument of Liberty because to them it seems to incarnate their own uplifting.”

The immigrants who would catch a glimpse of the statue would mainly come from eastern and southern Europe.

In 1900, fourteen percent of the American population was foreign born, compared to eight percent a century later. Passports were unnecessary and the cost of crossing the Atlantic was just ten dollars in steerage. Driving immigration from Europe were a combination of push and pull factors. A rapidly growing industrial economy’s needed low-wage labor.that would be supplied by many eastern and southern Europeans, whose lives were disrupted by imported foodstuffs and industrially produced goods. Many of these “new” immigrants, in turn, viewed the United States as a land of opportunity and greater freedom.

European immigration to the United States greatly increased after the Civil War, reaching 5.2 million in the 1880s then surging to 8.2 million in the first decade of the twentieth century. Between 1882 and 1914, approximately twenty million immigrants came to the United States. In 1907 alone, 1.285 million arrived. By 1900, New York City had as many Irish residents as Dublin. It had more Italians than any city outside Rome and more Poles than any city except Warsaw. It had more Jews than any other city in the world, as well as sizeable numbers of Slavs, Lithuanians, Chinese, and Scandinavians.

Unlike earlier immigrants, who mainly came from northern and western Europe, the “new immigrants” who came largely from the Balkans, Italy, Poland, and Russia, were largely Catholic and Jewish in religion.

Birds of Passage

Many of the millions of immigrants who arrived into the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did so with the intention of returning to their villages in the Old World. Known as “birds of passage,” many of these eastern and southern European migrants were peasants who had lost their property as a result of the commercialization of agriculture. They came to America to earn enough money to allow them to return home and purchase a piece of land. As one Slavic steelworker put it: “A good job, save money, work all time, go home, sleep, no spend.”

Many of these immigrants came to America alone, expecting to rejoin their families in Europe within a few years. From 1907 to 1911, of every hundred Italians who arrived in the United States, 73 returned to the Old Country. For Southern and Eastern Europe as a whole, approximately 44 of every 100 who arrived returned back home.

Some immigrants, however, did not come as “sojourners.” In particular, Jewish immigrants from Russia, fleeing religious persecution, came in family groups and intended to stay in the United States from the beginning.

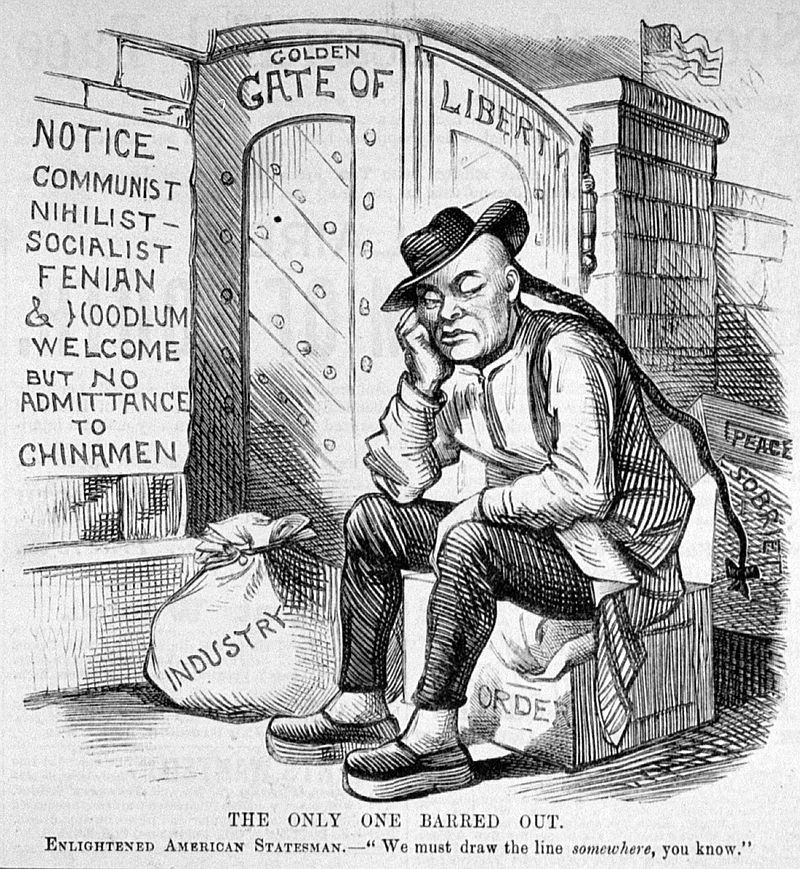

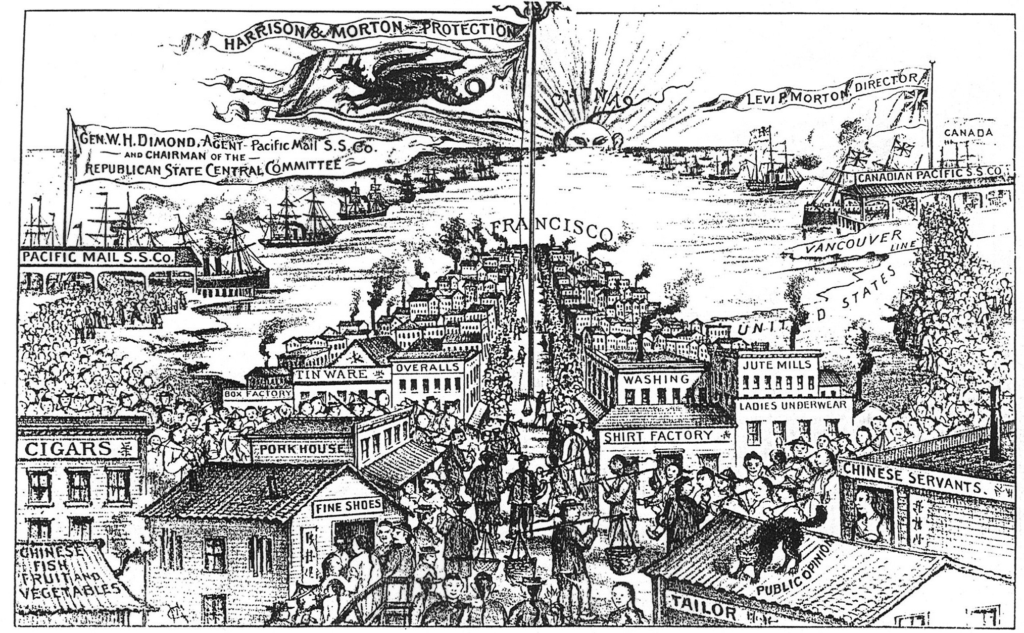

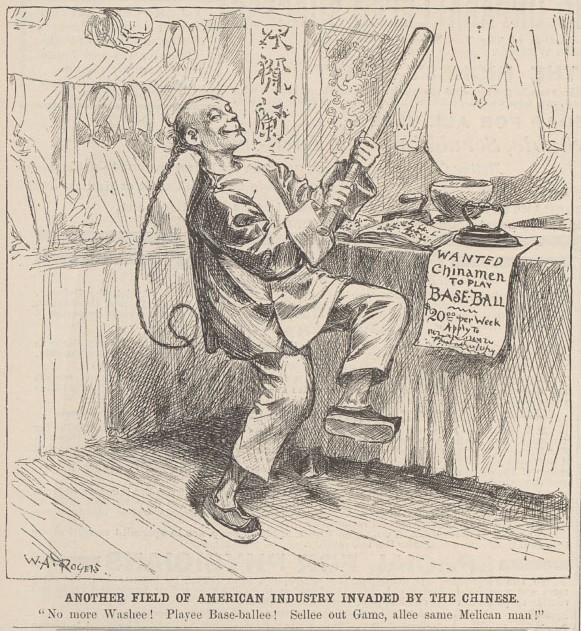

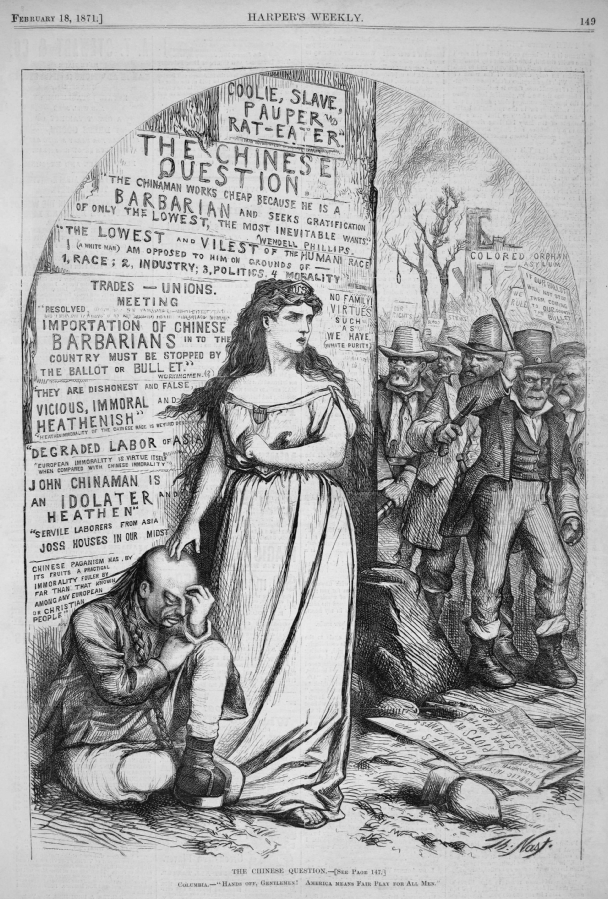

Chinese Exclusion Act

From 1882 until 1943, most Chinese immigrants were barred from entering the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the nation’s first law to ban immigration by race or nationality. All Chinese people—except travelers, merchants, teachers, students, and those born in the United States—were barred from entering the country. Federal law prohibited Chinese residents, no matter how long they had legally worked in the United States, from becoming naturalized citizens.

From 1850 to 1865, political and religious rebellions within China left thirty million dead and the country’s economy in a state of collapse. Meanwhile, the canning, timber, mining, and railroad industries on the United States’ West Coast needed workers. Chinese business owners also wanted immigrants to staff their laundries, restaurants, and small factories.

Smugglers transported people from southern China to Hong Kong, where they were transferred onto passenger steamers bound for Victoria, British Columbia. From Victoria, many immigrants crossed into the United States in small boats at night. Others crossed by land.

The Geary Act, passed in 1892, required Chinese aliens to carry a residence certificate with them at all times upon penalty of deportation. Immigration officials and police officers conducted spot checks in canneries, mines, and lodging houses and demanded that every Chinese person show these residence certificates.

Due to intense anti-Chinese discrimination, many merchants’ families remained in China while husbands and fathers worked in the United States. Since Federal law allowed merchants who returned to China to register two children to come to the United States, men who were legally in the United States might sell their testimony so that an unrelated child could be sponsored for entry. To pass official interrogations, immigrants were forced to memorize coaching books which contained very specific pieces of information, such as how many water buffalo there were in a particular village. So intense was the fear of being deported that many “paper sons” kept their false names all their lives. The U.S. government only gave amnesty to these “paper families” in the 1950s.

Angel Island

Most Americans have heard of Ellis Island, the demarcation point in New York harbor where millions of European immigrants entered the United States.

There was also an “Ellis Island of the West.” Located in San Francisco Bay, Angel Island was also a check point for immigrants in the early years of the twentieth century. But only a small proportion of the 175,000 people who arrived at Angel Island were allowed to remain in the United States. Angel Island was a detention center for Chinese immigrants. It was surrounded by barbed wire.

Thirteen-year-old Jack Moy and his mother sailed to the United States in 1927. The two spent a month in the detention center separated from one another. Immigration officials asked insulting personal questions, such as whether their mother had bound feet or how many water buffalo a village had or “who occupies the house on the fifth lot of your row in your native village.” Discrepancies in an answer could mean deportation to China. Immigration officials marked down every identifying mark, including scars, boils, and moles.

To join her husband in the United States, Suey Ting Gee had to pretend that she was the wife of another man. Under a U.S. law in effect from 1882 to 1943, the Chinese wives of resident alien laborers could not join them in this country.

To learn more about Angel Island, listen to this podcast.

Japanese Immigration

Overpopulation and rural poverty led many Japanese to emigrate to the United States, where they confronted intense racial prejudice. In California, the legislature imposed limits on Japanese land ownership, and the Hearst newspaper ran headlines such as ”The Yellow Peril: How Japanese Crowd out the White Race.”

The San Francisco School Board stirred an international incident in 1906 when it segregated Japanese students in an “Oriental School.” The Japanese government protested to President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt negotiated a”gentlemen’s agreement”restricting Japanese emigration.

Contract Labor

During the nineteenth century, demand for manual laborers to build railroads, raise sugar on Pacific Islands, mine precious metals, construct irrigation canals, and perform other forms of heavy labor, grew. Particularly in tropical or semi-tropical regions, this demand for manual labor was met by indentured or contract workers. Nominally free, these laborers served under contracts of indenture which required them to work for a period of time—usually five to seven years—in return for their travel expenses and maintenance. In exchange for nine hours of labor a day, six days a week, indentured servants received a small salary as well as clothing, shelter, food, and medical care.

An alternative to the indenture system was the “credit ticket system.” A broker advanced the cost of passage and workers repaid the loan plus interest out of their earnings. The ticket system was widely used by Chinese migrants to the United States. Beginning in the 1840s, about 380,000 Chinese laborers migrated to the U.S. mainland and 46,000 to Hawaii. Between 1885 and 1924, some 200,000 Japanese workers went to Hawaii and 180,000 to the U.S. mainland.

Indentured laborers are sometimes derogatorily referred to as “coolies.” Today, this term carries negative connotations of passivity and submissiveness, but originally it was an Anglicization of a Chinese word that refers to manual workers impressed into service by force or deception. In fact, indentured labor was frequently acquired through deceptive practices and even violence.

Between 1830 and 1920, about 1.5 million indentured laborers were recruited from India, one million from Japan, and half a million from China. Tens of thousands of free Africans and Pacific Islanders also served as indentured workers.

The first Indian indentured laborers were imported into Mauritius, an island in the Indian Ocean, in 1830. Following the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833, tens of thousands of Indians, Chinese, and Africans were brought to the British Caribbean. After France abolished slavery in 1848, its colonies imported 80,000 Indian laborers and 19,000 Africans. Also ending slavery in 1848, Dutch Guiana recruited 57,000 Asian workers for its plantations. Although slavery was not abolished in Cuba until 1886, the rising costs of slaves led plantations to recruit 138,000 indentured laborers from China between 1847 and 1873.

Areas that had never relied on slave labor also imported indentured workers. After 1850, American planters in Hawaii recruited labor from China and Japan. British planters in Natal in southern Africa recruited Indian laborers and those in Queensland in northeastern Australia imported laborers from neighboring South Pacific Islands. Other indentured laborers toiled in East Africa, on Pacific Islands such as Fiji, and in Chile, where they gathered bird droppings known as guano for fertilizer.

Steam transportation allowed Europeans and their descendants to extract “surplus” labor from overpopulated areas suffering from poverty and social and economic dislocation. In India, the roots of migration included unemployment, famine, demise of traditional industries, and the demand for cash payment of rents. In China, a society with a long history of long-distance migration, causes of migration included overpopulation, drought, floods, and political turmoil, culminating in the British Opium Wars (1839-1842 and 1856 and 1860) and the Taiping Rebellion, which may have cost twenty to thirty million lives.

Overwhelmingly male, many indentured workers initially thought of themselves as sojourners who would reside temporarily in the new society. In the end, however, many indentured laborers remained in the regions where they worked. As a result, the descendants of indentured laborers make up a third of the population in British Guiana, Fiji, and Trinidad by the early twentieth century.

Some societies, such as the United States, passed legislation that hindered the migration of Asian women. In contrast, the British Caribbean colonies required forty women to be recruited for every one hundred men to promote family life.

Immigration Restriction

Gradually during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the United States imposed restrictions on immigration. In 1882, those who were excluded included people likely to become public charges. The United States subsequently prohibited the immigration of contract laborers (1885) and illiterates (1917), and all Asian immigrants,except for Filipinos, who were U.S. nationals (1917). Other acts restricted the entry of certain criminals, people who were considered immoral, those suffering from certain diseases, and paupers. Under the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907-1908, the Japanese government agreed to limit passports issued to Japanese in order to permit wives to enter the United States. Intolerance toward immigrants from southern and eastern Europe resulted in the Immigration Act of 1924, which placed a numerical cap on immigration and instituted a deliberately discriminatory system of national quotas. In 1965, the United States adopted a new immigration law which ended the quota system.

During the twentieth century, all advanced countries imposed restrictions on the entry of immigrants. A variety of factors encouraged immigration restriction. These include a concern about the impact of immigration on the economic well-being of a country’s workforce as well as anxiety about the feasibility of assimilating immigrants of diverse ethnic and cultural origins. Especially following World War I and World War II, countries expressed concern that foreign immigrants might threaten national security by introducing alien ideologies.

It is only in the twentieth century that governments became capable of effectively enforcing immigration restrictions. Before the twentieth century, Russia was the only major European country to enforce a system of passports and travel regulations. During and after World War I, however, many western countries adopted systems of passports and border controls as well as more restrictive immigration laws. The Russian Revolution prompted fear of foreign radicalism, while many countries feared that their societies would be overwhelmed by a postwar surge of refugees.

Among the first societies to adopt restrictive immigration policies were Europe’s overseas colonies. Apart from prohibitions on the slave trade, many of the earliest immigration restrictions were aimed at Asian immigrants. The United States imposed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. It barred the entry of Chinese laborers and established stringent conditions under which Chinese merchants and their families could enter. Canada also imposed restrictions on Chinese immigration. It imposed a “head” tax (which was $500 in 1904) and required migrants to arrive by a “continuous voyage.”

Terms to know:

- Xenophobia: Hatred of foreigners and immigrants.

- Nativism: The policy of keeping a society ethnically homogenous.

Migration and Disease

Throughout history, the movement of people has played a critical role in the transmission of infectious disease. As a result of migration, trade, and war, disease germs have traveled from one environment to others. As intercultural contact has increased—as growing numbers of people traveled longer distances to more diverse destinations—the transmission of infectious diseases has increased as well.

No part of the globe has been immune from this process of disease transmission. In the 1330s, bubonic plague spread from central Asia to China, India, and the Middle East. In 1347, merchants from Genoa and Venice carried the plague to Mediterranean ports. The African slave trade carried yellow fever, hookworm, and African versions of malaria into the New World. During the early nineteenth century, cholera spread from northeast India to Ceylon, Afghanistan, and Nepal. By 1826, the disease had reached the Arabian Peninsula, the eastern coast of Africa, Burma, China, Japan, Java, Poland, Russia, Thailand, and Turkey. Austria, Germany, Poland, and Sweden were struck by the disease by 1829, and within two more years, cholera had reached the British Isles. In 1832, the disease arrived in Canada and the United States.

Epidemic diseases have had far-reaching social consequences. The most devastating pandemic of the twentieth century, the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918 and 1919, killed well over twenty million people around the world—many more people than died in combat in World War I. Resulting in such complications as pneumonia, bronchitis, and heart problems, the Spanish Flu had a particularly devastating impact in Australia, Canada, China, India, Persia, South Africa, and the United States. Today, the long-distance transfer of disease continues, evident, most strikingly with AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome), which many researchers suspect originated in sub-Saharan Africa.

Disease played a critically important role in the success of European colonialism. After 1492, Europeans carried diphtheria, influenza, measles, mumps, scarlet fever, smallpox, tertian malaria, typhoid, typhus, and yellow fever to the New World, reducing the size of the indigenous population fifty to ninety percent. Measles killed one fifth of Hawaii’s people during the 1850s and a similar proportion of Fiji’s indigenous population in the 1870s. Influenza flu, measles, smallpox, and whooping cough reduced the Maoris population of New Zealand from about 100,000 in 1840 to 40,000 in 1860.

Fear of contagious diseases assisted nativists in the United States in their efforts to restrict foreign immigration. The 1890s was a decade of massive immigration from eastern Europe. When 200 cases of typhus appeared among Russian Jewish immigrants who had arrived in New York on French steamship in 1892, public health authorities acted swiftly. They detained the 1,200 Russian Jewish immigrants who had arrived on the ship and placed them in quarantine to keep the epidemic from spreading. The chairman of the U.S. Senate Committees on Immigration subsequently proposed legislation severely restricting immigration, including the imposition of a literacy requirement.

Fear that immigrants carried disease mounted with news of an approaching cholera pandemic. The epidemic, which had begun in India in 1881, did not subside until 1896, when it had spread across the Far East, Middle East, Russia, Germany, Africa, and the Americas. More than 300,000 people died of cholera in famine-stricken Russia alone.

To prevent the disease from entering the United States, the port of New York in 1892 imposed a twenty-day quarantine on all immigrant passengers who traveled in steerage. This measure, which did not apply to cabin-class passengers, was designed to halt foreign immigration, since few steamships could afford to pay $5,000 a day in daily port fees. Other cities including Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit, imposed quarantines on immigrants arriving in local railroad stations. Congress in 1893 adopted the Rayner-Harris National Quarantine Act which set up procedures for the medical inspection of immigrants and permitted the president to suspend immigration on a temporary basis.

A fear that impoverished immigrants will carry disease into the United States has recurred during the twentieth century. In 1900, after bubonic plague appeared in San Francisco’s Chinatown, public health officials in San Francisco quarantined Chinese residents. In 1924, a pneumonia outbreak resulted in the quarantining of Mexican immigrants. After Haitian immigrants were deemed to be at high risk of AIDS during the 1980s, they were placed under close scrutiny by immigration officials.

Questions to think about:

- What factors might make a specific population particularly vulnerable to disease?

- In your view should immigrants be viewed as a possible source of disease? Or is such a fear overdrawn?