The Rise of Mass Communication and Culture

The Rise of Mass Communication

The last ten years of the nineteenth century were critical in the emergence of modern American mass culture. In those years emerged the modern instruments of mass communication—the mass-circulation metropolitan newspaper, the best-seller, the mass-market magazine, national advertising campaigns, radio, and the movies. American culture also made a critical shift to commercialized forms of entertainment.

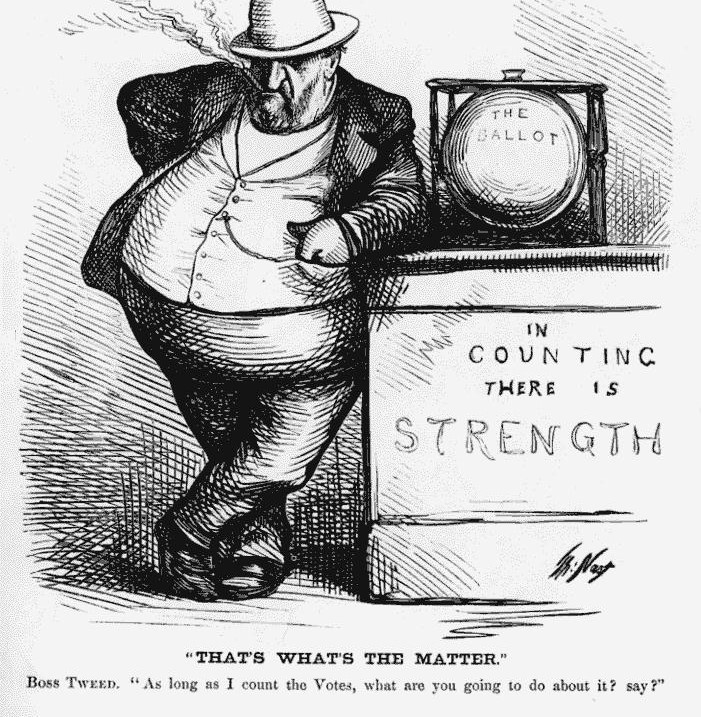

The Mass Market Newspaper

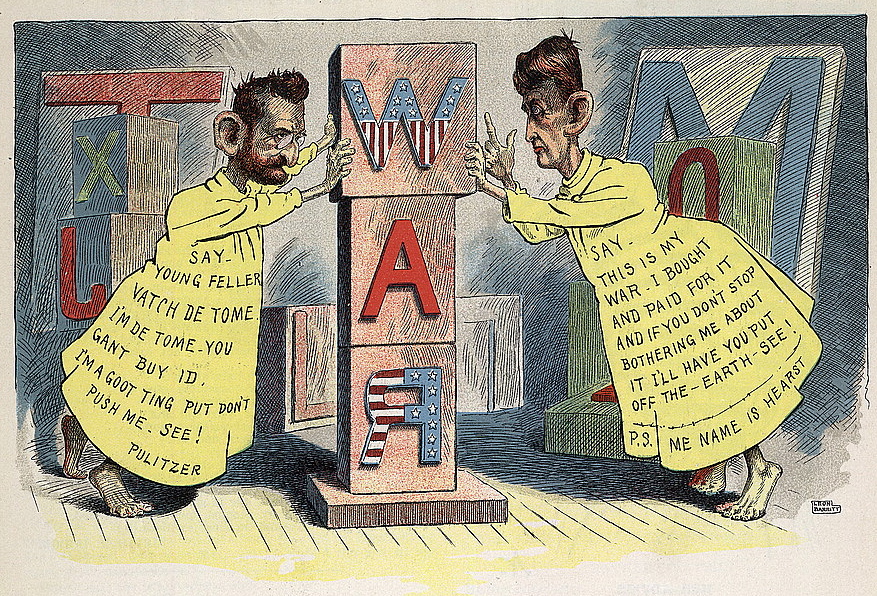

The urban tabloid was the first instrument to appear. It was pioneered by Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, and E.W. Scripp’s St. Louis Post-Dispatch. These popular newspapers differed dramatically from the upper-class and staunchly partisan political newspapers that had dominated nineteenth-century journalism. They featured banner headlines, a multitude of photographs and cartoons, and an emphasis on local news, crime, scandal, society news, and sports. Large ads made up half a paper’s content, compared to just thirty percent in earlier newspapers. For easier reading on street railways, page size was cut, stories were shortened, and the text heavily illustrated.

The Hungarian born Pulitzer migrated to the United States at the age of seventeen and purchased the struggling New York World from financier Jay Gould. His newspaper crusaded against corruption and fraud. He pledged that the World would be “dedicated to the cause of the people rather than that of the purse-potentates” and would “expose all fraud and sham, fight all public evils and abuses…[and] serve and battle for the people.” Using simple words, a lively style, and many illustrations, his newspaper could be read by many immigrants who understood little English. By 1905, the World had a circulation of two million.

Hearst developed the newspaper’s entertainment potential. Entertainment was stock in trade of yellow journalism (named for the “yellow kid” comic strip that appeared in the Journal). Among the innovations he pioneered were the first color comic strips, advice columns, women’s pages, fashion pages, and sports pages.

Scripps’s legacy was the development of the business side of the modern American newspaper. From the early 1870s through his retirement in 1908, he established or bought more than forty newspapers, stretching from Portland, Oregon, to New York City. His biggest innovations were a national news service and a feature syndicate that provided all of his newspapers with common material. He claimed that he only needed two employees—a reporter and an editor—to start a newspaper, because he could rely on his news service and features syndicate. Syndicated material accounted for twenty-five to thirty-five percent of each issue and, at times, even up to half or three-quarters.

Instead of directly competing for established readers, Pulitzer instead sought to serve new readers. In his opinion, most newspapers either ignored or were hostile to the working class. His news stressed labor issues and was directed to a less-educated audience. His newspapers sold for just a penny at a time when others sold for two cents for home delivery and five cents on the street. His papers were half the size of other papers of the time.

His papers exposed trusts, supported strikes, and favored government regulation of food and transportation industries, as well as government ownership of water and electric utilities. They advocated power for the common people by direct election of public office and through initiative, referendum, and recall. They offered advice on how to run a home on a limited budget.

The Mass Circulation National Magazine, the Bestseller, and Records

Also during the 1890s the world of magazine publishing was revolutionized by the rise of the country’s first mass circulation national magazines. After the Civil War, the magazine field was dominated by a small number of sedate magazines—like The Atlantic, Harper’s, and Scribner’s—written for “gentle” reader with highly intellectual tastes. The poetry, serious fiction, and wood engravings that filled these monthly’s pages rigidly conformed to upper-class Victorian standards of taste. These magazines embodied what the philosopher George Santayana called the “genteel tradition,” the idea that art and literature should reinforce morality not portray reality. Art and literature, the custodians of culture believed, should transcend the real and uphold the ideal. Poet James Russell Lowell spoke for other genteel writers when he said that no man should describe any activity that would make his wife or daughter blush.

The founders of the nation’s first mass-circulation magazines considered the older “quality” magazines stale and elitist. In contrast, their magazines featured practical advice, popularized science, gossip, human interest stories, celebrity profiles, interviews, “muckraking” investigations, pictures, articles on timely topics—and a profusion of ads. Instead of cultivating a select audience, the new magazines had a very different set of priorities. By running popular articles, editors sought to maximize circulation, which, in turn, attracted advertising that kept the magazine’s price low. By 1900, the nation’s largest magazine, The Ladies’ Home Journal reached 850,000 subscribers—more than eight times the readership of Scribner’s or Harper’s.

The end of the nineteenth century also marked a critical turning point in the history of book publishing, as marketing wizards like Frank Doubleday organized the first national book promotional campaigns, created the modern best seller, and transformed popular writers like Jack London into celebrities. The world of the Victorian man of letters, the defender of “Culture” against “Anarchy,” had ended.

At the International Exposition in Paris in 1878, 30,000 people lined up to see the first demonstration of Thomas Edison’s phonograph. The phonograph was treated as a dictation machine for a decade after Thomas Edison invented it in 1877. It was not until 1890 that cylinders of recorded music were first sold. In 1901, cylinders gave way to discs.

Advertising

In 1898, the National Biscuit Company (Nabisco) launched the first million-dollar national advertising campaign. It succeeded in making Uneeda biscuits and their water-proof “In-er-Seal” box popular household items. During the 1880s and 1890s, patent medicine manufacturers, department stores, and producers of low price packaged consumer goods (like Campbell Soups, H.J. Heinz, and Quaker Oats), developed modern advertising techniques. Where earlier advertisers made little use of brand names illustrations, or trademarks, the new ads made use of snappy slogans and colorful packages. As early as 1900, advertisements began to use psychology to arouse consumer demand by suggesting that a product would contribute to the consumer’s social and psychic well-being. To induce purchases, observed a trade journal in 1890, a consumer “must be aroused, excited, terrified.” Listerine mouthwash promised to cure “halitosis.” Scott tissue claimed to prevent infections caused by harsh toilet paper.

By stressing instant gratification and personal fulfillment in their ads, modern advertising helped undermine an earlier Victorian ethos emphasizing thrift, self-denial, delayed gratification, and hard work. In various ways, it transformed Americans from “savers” to “spenders” and told them to give in to their desire for luxury.

History Through…

…Food

Food is much more than a mere means of subsistence. It is filled with cultural, psychological, emotional, and even religious significance. It defines shared identities and embodies religious and group traditions. In Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, food served as a class marker. A distinctive court tradition of haute cuisine and elaborate table manners arose, distinguishing the social elite from the hoi polloi. During the nineteenth centuries, food became a defining symbol of national identity. It is a remarkable fact that many dishes that we associate with particular countries—such as the tomato-based Italian spaghetti sauce or the American hamburger—are nineteenth or even twentieth century inventions.

The European discovery of the New World represented a momentous turning point in the history of food. Foods previously unknown in Europe and Africa, such as tomatoes, potatoes, corn, yams, cassava, manioc, and a vast variety of beans migrated eastward, while other sources of food, unknown in the Americas including pigs, sheep, and cattle—moved westward. Sugar, coffee, and chocolate grown in the New World became the basis for the world’s first truly multinational consumer-oriented industries.

Until the late nineteenth century, the history of food in America was a story of fairly distinct regional traditions that stemmed largely from England. The country’s earliest English, Scottish, and Irish Protestant migrants tended to cling strongly to older food traditions. Yet the presence of new ingredients, and especially contact among diverse ethnic groups, would eventually encourage experimentation and innovation. Nevertheless, for more than two centuries, English food traditions dominated American cuisine.

Before the Civil War, there were four major food traditions in the United States, each with English roots. These included a New England tradition that associated plain cooking with religious piety. Hostile toward fancy or highly seasoned foods, which they regarded as a form of sensual indulgence, New Englanders adopted an austere diet stressing boiled and baked meats, boiled vegetables, and baked breads and pies. A Southern tradition, with its high seasonings and emphasis on frying and simmering, was an amalgam of African, English, French, Spanish, and Indian foodways. In the middle Atlantic areas influenced by Quakerism, the diet tended to be plain and simple and emphasized boiling, including boiled puddings and dumplings. In frontier areas of the backcountry, the diet included many ingredients that other English used as animal feed, including potatoes, corn, and various greens. The backcountry diet stressed griddle cakes, grits, greens, and pork.

One unique feature of the American diet from an early period was the abundance of meat—and distilled liquor. Abundant and fertile lands allowed settlers to raise corn and feed it to livestock as fodder, and convert much of the rest into whiskey. By the early nineteenth century, adult men were drinking more than seven gallons of pure alcohol a year.

One of the first major forces for dietary change came from German immigrants, whose distinctive emphasis on beer, marinaded meats, sour flavors, wursts, and pastries was gradually assimilated into the mainstream American diet in the form of barbeque, coleslaw, hot dogs, donuts, and hamburgers. The German association of food with celebrations also encouraged other Americans to make meals the centerpiece of holiday festivities.

An even greater engine of change came from industrialization. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, food began to be mass produced, mass marketed, and standardized. Factories processed, preserved, canned, and packaged a wide variety of foods. Processed cereals, which were originally promoted as one of the first health foods, quickly became a defining feature of the American breakfast. During the 1920s, a new industrial technique—freezing—emerged, as did some of the earliest cafeterias and chains of lunch counters and fast food establishments. Increasingly processed and nationally distributed foods began to dominate the nation’s diet. Nevertheless, distinct regional and ethnic cuisines persisted.

During the early twentieth century, food became a major cultural battleground. The influx of large numbers of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe brought new foods to the United States. Settlement house workers, and food nutritionists, and domestic scientists tried to “Americanize” immigrant diets and teach immigrant wives and mothers “American” ways of cooking and shopping. Meanwhile, muckraking journalists and reformers raised questions about the health, purity, and wholesomeness of food, leading to the passage of the first federal laws banning unsafe food additives and mandating meat inspection.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, change in American foodways took place slowly, despite a steady influx of immigrants. Since World War II, and especially since the 1970s, shifts in eating patterns have greatly accelerated. World War II played a key role in making the American diet more cosmopolitan. Overseas service introduced soldiers to a variety of foreign cuisines, while population movements at home exposed to a wider variety of American foodways. The post-war expansion of international trade also made American diets more diverse, making fresh fruits and vegetables available year-round.

Today, food tends to play a less distinctive role in defining ethnic or religious identity. Americans, regardless of religion or region, eat bagels, curry, egg rolls, and salsa—and a Thanksgiving turkey. Still, food has become—as it was for European aristocrats—a class marker. For the wealthier segments of the population, dining often involves fine wines and artistically prepared foods made up of expensive ingredients. Expensive dining has been very subject to fads and shifts in taste. Less likely to eat German or even French cuisine, wealthier Americans have become more likely to dine on foods influenced by Asian or Latin American cooking.

Food also has assumed a heightened political significance. The decision to adopt a vegetarian diet or to eat only natural foods has become a conscious way to express resistance to corporate foods. At the same time, the decision to eat particular foods has become a conscious way to assert one’s ethnic identity.

The Purveyors of Mass Culture

The creators of the modern instruments of mass culture tended to share a common element in their background. Most were “outsiders”—recent immigrants or Southerners, Midwesterners, or Westerners. Joseph Pulitzer was an Austrian Jew, the pioneering “new” magazine editors, Edward W. Bok and Samuel Sidney McClure, were also first-generation immigrants. Where the “genteel tradition” was dominated by men and women from Boston’s elite culture or upper-class New York, the men who created modern mass culture had their initial training in daily newspapers, commerce, and popular entertainment—and, as a result, were more in touch with popular tastes. As outsiders, the creators of mass culture betrayed an almost voyeuristic interest in what they called the “romance of real life,” with high life, low life, power, and status.

The new forms of popular culture that they helped create shared a common style: simple, direct, realistic, and colloquial. The 1890s were the years when a florid Victorian style was overthrown by a new “realistic” aesthetic. At various levels of American culture, writers and artists rebelled against the moralism and sentimentality of Victorian culture and sought to live objectively and truthfully, without idealization or avoiding the ugly. The quest for realism took a variety of guises. It could be seen in the naturalism of writers like Theodore Dreiser and Stephen Crane, with their nightmarish depictions of urban poverty and exploitation, in the paintings of the “ashcan” school of art, with their vivid portraits of tenements and congested streets, and in the forceful, colorful prose of tabloid reporters and muckraking journalists, who cut through the Victorian veil of reticence surrounding such topics as sex, political corruption, and working conditions in industry.

Mass Culture Blossoms

Although they relied on nineteenth-century inventions, the most influential innovations in mass culture would take place after the turn-of-the-century. Thomas Edison first successfully projected moving pictures on a screen in 1896, but it would not be until 1903 that Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery—the first American movie to tell a story—demonstrated the commercial appeal of motion pictures. And while Guglielmo Marconi proved the possibility of wireless communication in 1895, commercial radio broadcasting did not begin until 1920 and commercial television broadcasts until 1939. In the twentieth century, these new instruments of mass communication would reach audiences of unprecedented size. By 1922, movies sold forty million tickets a week and radios could be found in three million homes.

The emergence of these modern forms of mass communication had far-reaching effects upon American society. They broke down the isolation of local neighborhoods and communities and ensured that for the first time all Americans,—regardless of their class, ethnicity, or locality—began to share standardized information and entertainment.

Commercialized Leisure

Of all the differences between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, one of the most striking involves the rapid growth of commercialized entertainment. For much of the nineteenth century, commercial amusements were viewed as somehow suspect. Drawing on the Puritan criticisms of play and recreation and a Republican ideology that was hostile to luxury, hedonism, and extravagance, American Victorians tended to associate theaters, dance halls, circuses, and organized sports with such vices as gambling, swearing, drinking, and immoral sexual behavior. In the late nineteenth century, however, a new outlook—which revered leisure and play—began to challenge Victorian prejudices.

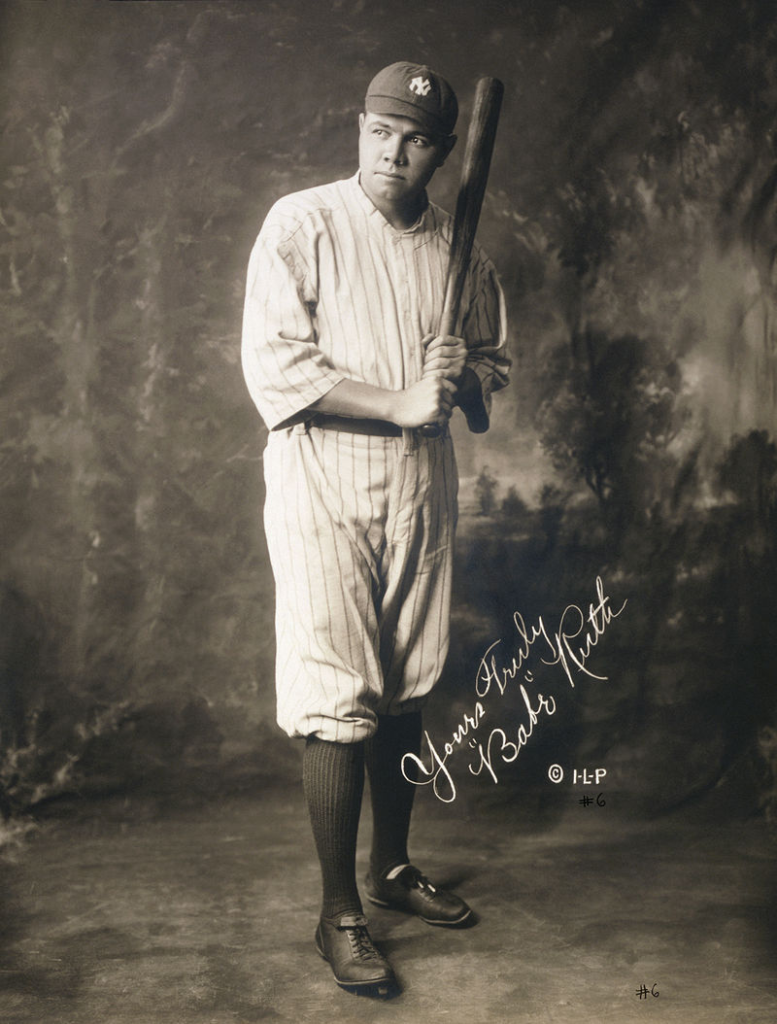

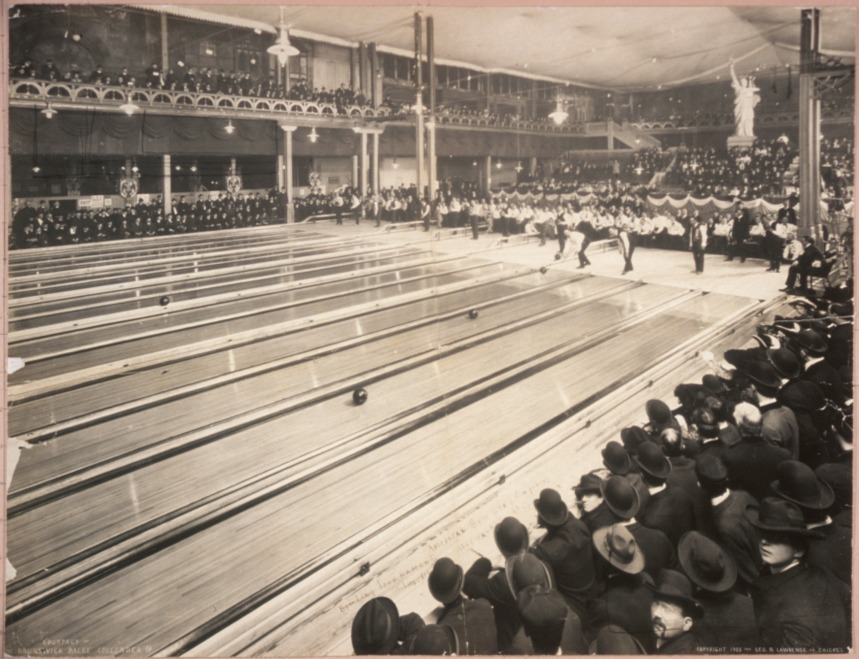

During the initial twenty years of the twentieth century, attendance at professional baseball games doubled. Vaudeville, too, increased in popularity, featuring singing, dancing, skits, comics, acrobats, and magicians. Amusement parks, penny arcades, dance halls, and other commercial amusements flourished. As early as 1910, when there were 10,000 movie theaters, the movies had become the nation’s most popular form of commercial entertainment.

The rise of these new kinds of commercialized amusements radically reshaped the nature of American leisure activities. Earlier in the nineteenth century leisure activities had been sharply segregated on the basis of gender, class, and ethnicity. The wealthy attended their own exclusive theaters, concert halls, museums, restaurants, and sporting clubs. For the working class, leisure and amusement was rooted in particular ethnic communities and neighborhoods, each with its own saloons, churches, fraternal organizations, and organized sports. Men and women participated in radically different kinds of leisure activities. Many men (particularly bachelors and immigrants) relaxed in barber shops, billiard halls, and bowling alleys, joined volunteer fire companies or militias, and patronized saloons, gambling halls, and race tracks. Women took part in church activities and socialized with friends and relatives.

After 1880, as incomes rose and leisure time expanded, new commercialized forms of cross-class, mixed-sex amusements proliferated. Entertainment became a major industry. Vaudeville theaters attracted women as well as men. The young, in particular, increasingly sought pleasure, escape, and the freedom to experiment free of parental control in mixed-sex crowds in relatively inexpensive amusement parks, dance halls, urban night clubs, and, above all, nickelodeons and movie theaters.

The transformation of Coney Island symbolized the emergence of a new leisure culture, emphasizing excitement, glamour, fashion, and romance. Formerly a center of male vice—of brothels, saloons, and gambling dens—Coney Island became the nation’s first modern amusement park, complete with ferris wheels, hootchie kootchie girls, restaurants, and concert halls. Its informality and sheer excitement attracted people of every class.

If Coney Island offered an escape from an oppressive urban landscape to an exotic one, the new motion picture industry would offer an even less expensive, more convenient escape. During the early twentieth century, it quickly developed into the country’s most popular and influential form of art and entertainment.

History Through…

…Sports

Sports occupy a central place in contemporary society. Our cities spend hundreds of millions of dollars on sports stadiums. Our newspapers devote a large proportion of their pages to sports, and television dedicates much of its programming to sports coverage. Our civic identity, and many of our conversations, revolve around sports.

Our vocabulary is filled with sports metaphors. Think: “hard ball,” “rain check,” “blind-sided,” “fumble,” “game plan,” “covering all the bases,” and “slam dunk.”

For much of the twentieth century, sports were truly a field of dreams, tied up with our deepest cultural myths: About the value of teamwork; of sports as a true meritocracy, where ethnicity and race made no difference; about Americanization and assimilation; and the testing ground for racial integration.

Thus it comes as a great surprise to discover that modern sports are less than two hundred years old. Competitive team sports and professional sports, with clearly defined rules and carefully-maintained records, are a relatively recent innovation.

Timeline of Sports History

1845 – Alexander Cartwright formalizes the first 20 rules of baseball

1855 – The first modern game of hockey is played in Kingston, Ontario, using rules similar to today’s.

1856 – Catherine Beecher (1800-78) publishes Physiology and Calisthenics for Schools and Families, the first fitness manual for women.

1863 – New Yorker James Plimpton uses a rubber cushion to enable the wheels of roller skates to turn slightly when a skater shifted his or her weight. This design is considered the basis for the modern roller skate, allowing for safer, controlled skating.

1864 – The Park Place Croquet Club of Brooklyn organizes with 25 members. Croquet is probably the first game played by both men and women in America.

1869 – Cincinnati Red Stockings become the first professional baseball team

1869 – Rutgers and Princeton played a college soccer football game, the first ever.

1874 – Mary Ewing Outerbridge of Staten Island introduces tennis to the United States.

1875 – Baseball glove introduced

1879 – The first National Archery Championship is held, with 20 women participating.

1881 – The first American national tennis championships are held.

1886 – The New York Athletic Club holds the first track and field meet in the U.S.

1888 – The modern “safety” bicycle is invented with a light frame and two equal-sized wheels and a chain drive.

1891 – Basketball is invented by James Naismith of the YMCA in Springfield, Massachusetts as an indoor sport to play between football and baseball seasons.

1894 – First auto race

1895 – First U.S. Open in golf

1895 – Volleyball is invented in Holyoke, Massachusetts.

1895 – The American Bowling Congress is organized, establishing equipment standards and rules.

1897 – Lena Jordan becomes the first person to successfully execute the triple somersault on the flying trapeze. The first man to accomplish this didn’t do so until 1909.

1899 – Ping-pong, or table tennis, as it soon becomes known, is invented.

1906 – The forward pass was legalized in football.

1939 – First NCAA Division I Basketball Tournament

1939 – Baseball Hall of Fame opens

1939 – First televised baseball game

1946 – Pro football integrates. Kenny Washington and Woody Strode sign with Los Angeles; Marion Motley and Bill Willis sign with Cleveland

1947 – Jackie Robinson integrates baseball

1947 – Althea Gibson, an African American woman, wins the first of ten consecutive American Tennis Association national championships.

1949 – The National Basketball Association was formed. It was a combination of the Basketball Association of America and the National Basketball League.

1950 – Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton, Chuck Cooper, and Earl Lloyd become the NBA first black players

1954 – NBA adopts the 24-second shot clock & 6 team-foul rule.

1960 – Wilma Rudolph, during the Olympic Games in Rome, becomes the first American woman to win 3 track and field gold medals – in the 100-meter dash, the 200 meter dash, and the 400 meter relay.

1967 – First Superbowl

1970 – American Football League and National Football League merge

1972 – The Education Act of 1972 is passed, which contains Title IX, prohibiting gender discrimination in educational institutions that receive federal funds.

1973 – Billie Jean King wins the “battle-of-the-sexes” tennis match against Bobby Riggs in Houston in front of more than 30,000 people and a world-wide TV audience of more than 50 million.

The Modern University

Colleges underwent profound changes after the Civil War. Before the war, colleges relied heavily on drill and rote memorization. These institutions prescribed almost all of a student’s course of study. Subjects that were viewed as too practical were excluded from the curriculum.

The Morrill Act, which granted land for higher education in each pro-Union state, had been opposed by Southerners on constitutional grounds and vetoed by President James Buchanan. It became law in 1862, in the midst of the Civil War. The Morrill Act specifically directed that the endowed institutions were “to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts.” The underlying idea was that educational institutions should support occupations in industry and the professions.

The Gilded Age gave birth to the major intellectual institution in modern American life: the research university. Modeled on German universities, these institutions did not simply train undergraduates. They also provided graduate and professional training in law, medicine, engineering, and other fields.

Within these new universities, the sciences received stature equal to that of the humanities and the curriculum was flexible and unrestricted. The elective system, promoted at Cornell and Harvard from the 1860s onward, made universities more attractive to a broader range of students and expanded the skills that they acquired. Cornell promptly provided programs in civil engineering. Cornell’s president, Andrew D. White, insisted that the institution prove its value by investigating social problems and training public leaders. But the new universities were also interested in knowledge for its own sake. They offered courses in areas that were not obviously practical, such as archaeology, astronomy, and Sanskrit.

By the 1890s, universities began to borrow organizations and procedures from business. University presidents delegated responsibility to subordinates known as the administration. University education was better organized numerically, with credit hours and grade points. The faculty divided into departments and divisions. Modern higher education had been born.