The Making of Modern America

“The Wizard of Menlo Park”

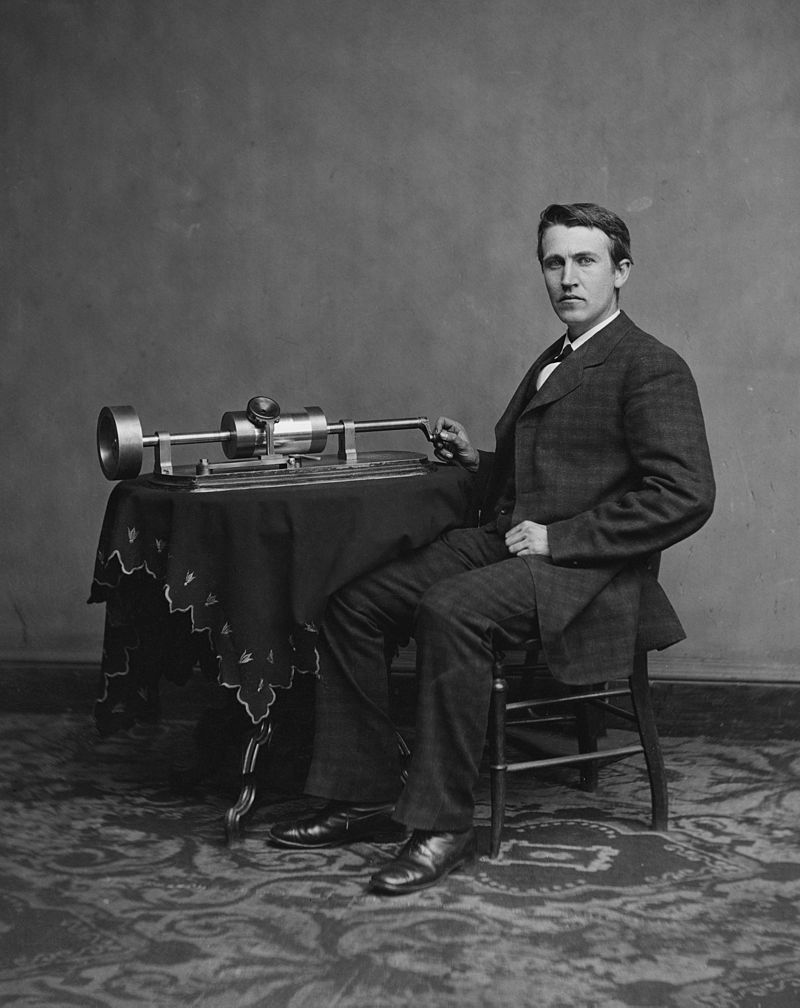

Far outshadowing partisan politics in importance during the Gilded Age were revolutionary innovations in technology that drastically altered everyday life. The electric light bulb, the phonograph, the movie projector, and a host of other stunning inventions ushered in a new era of American history. One individual in particular, Thomas Alva Edison, personified the technological inventiveness of the Gilded Age.

He was hailed as “The Wizard of Menlo Park.” The New York World, in 1901, called him “Our Greatest Living American, The Foremost Creative and Constructive Mind of This Country, Our True National Genius.” He was portrayed in the movies by two different Hollywood stars, Mickey Rooney and Spencer Tracy.

He had 1,093 patents to his name and paved the way for many electricity-based technologies years before the physics of electricity was understood. His inventions include the dictating machine, the electric light, the electrified railroad, the fluorescent lamp, the mimeograph machine, the movie camera, the phonograph, Portland cement, and wax paper. But his greatest invention was none of these—it was the development of the modern research laboratory and research team.

Born in rural Ohio in 1847, Thomas Edison was the archetypal self-made titan who rose from humble origins to become the most famous inventor in the world. He had little formal schooling and his outlook was quintessentially American: practical, optimistic, and suspicious of intellectuals. By the age of ten, he had a small chemical laboratory in his cellar and was operating a homemade telegraph. When he was twelve, he hawked newspapers, magazines, and candy on a train from seven in the morning until nine at night. He printed a newspaper and conducted experiments in the train’s baggage room. When one of his experiments started a fire, he lost his job.

He was partially deaf, and was ridiculed by other students and never completed grade school. When a teacher pronounced his mind “addled,” his mother took him out of school and taught him herself. His second wife would tap out conversations in Morse code on his knee. In later years, he said that his lack of hearing saved him from many distractions.

His started out as an itinerant telegraph operator, traveling from town to town; his first invention was a device that repeated Morse code at a slower speed, so he could more easily transcribe the messages. His first invention to make money was a ticker tape to convey stock market prices to brokerage houses. He became a millionaire in his forties.

He often worked twenty-four hours straight, except for five-minute naps. “Genius,” he said, “was one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.”

When he announced the phonograph in 1877, a Yale University professor told the New York Sun that “The idea of a talking machine is ridiculous.” After he announced that he had made an incandescent lamp, a board of inquiry convened by the British Parliament concluded that his claim was impossible and “unworthy of the attention of practical or scientific men.”

Contrary to popular belief, he did not invent the light bulb. Rather, he figured out how to make it a durable and inexpensive consumer item. He promised to make bulbs “so cheap that only the wealthy can afford to burn candles.” The key was to find a long-lasting filament. He tested over 6,000 different materials.

Far from being a solitary genius, Edison created the first modern research laboratory. Far from being a lone tinkerer, he employed as many as 200 laboratory assistants and machinists at his facilities in Menlo Park and West Orange, New Jersey. His West Orange factory had 10,000 employees in the mid-1910s. Edison demonstrated that it was possible to produce a steady stream of new inventions and technologies. Early in his career he said that his goal was “a minor invention every ten days and a big thing every six months or so.”

He was also the first inventor to develop links with major corporations that were willing to finance his inventions. He formed ties with Cornelius Vanderbilt, who owned Western Union, the telegraph company, and with J.P. Morgan, the banker.

He made some mistakes. He championed direct current (DC), when George Westinghouse pushed for alternating current (AC), which could move efficiently over long distances. He stuck with a battery-powered electric car, while Henry Ford put out a cheaper gas-powered model. He spent millions on pre-fabricated concrete houses.

A prankster, he nicknamed his children Dot and Dash and proposed to his second wife in Morse code.

An Age of Innovation

The late nineteenth century witnessed the birth of modern America. These years saw the advent of new technologies of communication, including the phonograph, the telephone, and radio. They also saw the rise of the mass media: of mass-circulation newspapers and magazines, best-selling novels, and million-dollar national advertising campaigns. These years witnessed the rise of commercialized entertainment, including the amusement park, the urban nightclub, the dance hall, and the first motion pictures. Many modern sports, including basketball, bicycling, football, and golf were introduced to the United States, as were new transportation technologies, such as the automobile, electric trains and trolleys, and, in 1903, the airplane. They also saw the birth of the modern research university.

In the span of a single decade, the country underwent a decisive series of shifts. Between 1896 and 1905 the economic depression of the mid-1890s ended and the Populist movement collapsed. A great merger movement consolidated American business. The Republican Party achieved dominance in national politics that it largely maintained until the Great Depression. A new wave of immigration from eastern and southern Europe altered the nation’s ethnic and religious composition. Laboratory-based science reshaped the practice of medicine. The United States emerged as a world power on the international scene. Improved communication facilitated the rapid rise of national organizations, complex bureaucracies, and professionalization. At the same time, communication, entertainment, and transportation were revolutionized.

The Birth of Modern Culture

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, a New York neurologist named George M. Beard coined the term “neurasthenia” to describe a psychological ailment that afflicted a growing number of Americans. Neurasthenia’s symptoms included “nervous dyspepsia, insomnia, hysteria, hypochondria, asthma, sick-headache, skin rashes, hay fever, premature baldness, inebriety, hot and cold flashes, nervous exhaustion, brain-collapse, or forms of ‘elementary insanity.’” Among those who suffered from neurasthenia-like symptoms at some point in their lives were Theodore Roosevelt, settlement house founder Jane Addams, psychologist William James, painter Frederic Remington, and novelist Theodore Dreiser.

According to expert medical opinion, neurasthenia’s underlying cause was “over-civilization.” The frantic pace of modern life, nervous overstimulation, stress, and emotional repression produced debilitating bouts of depression, anxiety attacks, and nervous prostration. Fears of over-civilization pervaded late nineteenth century American culture. Social critics worried that urban life was producing a generation of pathetic, pampered, physically and morally enfeebled 97 pound weaklings. Modern Americans, in this view, were poor successors to the stalwart Americans who had fought the Civil War and tamed a continent.

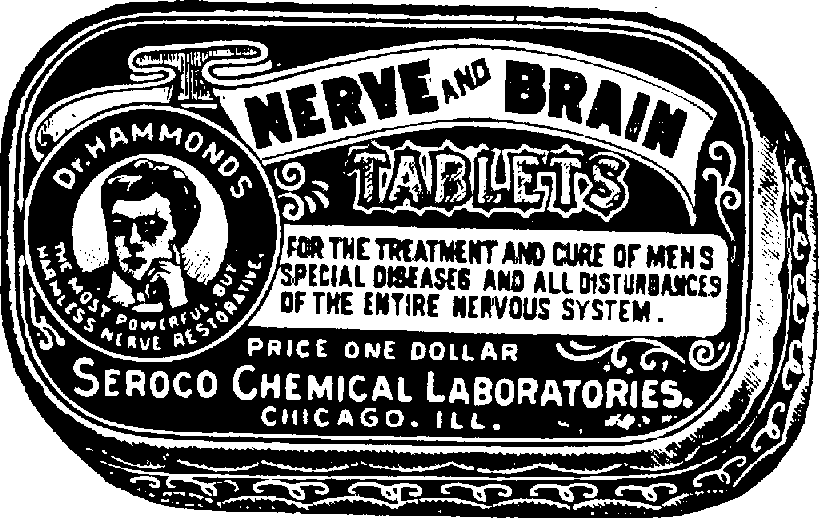

A sharply falling birth rate sparked fears that the native-born middle class was, in Theodore Roosevelt’s words, committing “race suicide” by allowing their numbers to be swamped by a flood of immigrants. A host of therapies promised to relieve the symptoms of neurasthenia, including such precursors of modern tranquilizers as Dr. Hammond’s Nerve and Brain Pills.

Sears even sold an electrical contraption called the Heidelberg Electric Belt, designed to reduce anxiety by sending electric shocks to the genitals. Many physicians prescribed physical exercise for men and rest cures for women. But the main form of release for late nineteenth century Americans from the pressures, stresses, and restrictions of modern life was by turning to sports, outdoor activities, and a vibrant popular culture.

Few Americans are unfamiliar with the wrenching economic transformations of the late nineteenth century, the consolidation of industry, the integration of the national economy, and the rise of the corporation. But few Americans realize that this period also saw the birth of modern culture.

In the last years of the nineteenth century, an ethos of self-fulfillment, leisure and sensual satisfaction began to replace the Victorian spirit of self-denial, self-restraint, and domesticity. Visual images took their place beside words and reading, which had been the essence of Victorian high learning. A new respect for energy, strength, and virility overtook the genteel endorsement of eternal truths and high moral ideals. Above all, a varied culture deeply divided by class, gender, religion, ethnicity, and locality gave way to a vibrant, commercialized mass culture that provided all Americans with standardized entertainment and information.

The Revolt against Victorianism

The new mood could be seen in a rage for competitive athletics and team sports. It was in the 1890s that boxing began to rival baseball as the nation’s most popular sport, basketball was invented, football swept the nation’s college campuses, and golf, track, and wrestling became popular pastimes. The celebration of vigor could also be seen in a new enthusiasm for such outdoor activities as hiking, hunting, fishing, mountain climbing, camping, and bicycling.

A new bold, energetic spirit was also apparent in popular music, in a craze for ragtime, jazz, and patriotic military marches. The culture of toughness and virility appeared in the growth of nationalism (culminating in 1898 in America’s “Splendid Little War” against Spain, the condemnation of sissies and stuffed shirts, and the growing popularity of aggressively masculine western novels such as Owen Wister’s, The Virginian.

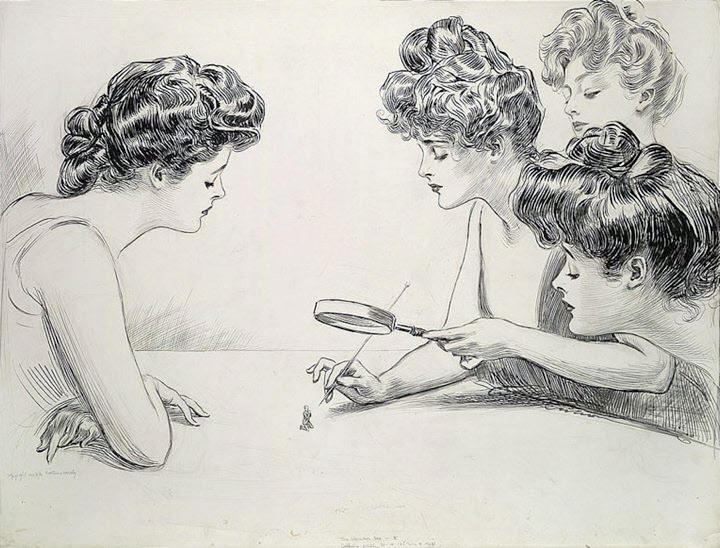

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the New Woman—personified by the tall, athletic Gibson Girl—supplanted the frail, submissive Victorian woman as a cultural ideal. The new woman began to work outside the home in increasing numbers, attend high school and college, and, increasingly, press for the vote. During the 1890s, American popular culture was in a full-scale revolt against the stifling Victorian code of propriety.

During the mid-nineteenth century, urban reformers had responded to the rapid growth of cities by advocating the construction of parks to serve as rural retreats in the midst of urban jungles. Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of New York City’s Central Park, believed that the park’s bucolic calm would instill the values of sobriety and self-control in the urban masses. But by the end of the century, it was clear that those masses had grown tired of sobriety and self-control. This was clearly seen at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, where the most popular area was the boisterous, rowdy Midway. Here, visitors rode the ferris wheel and watched “Little Egypt” and “hootchie-koochie girls” perform exotic dances.

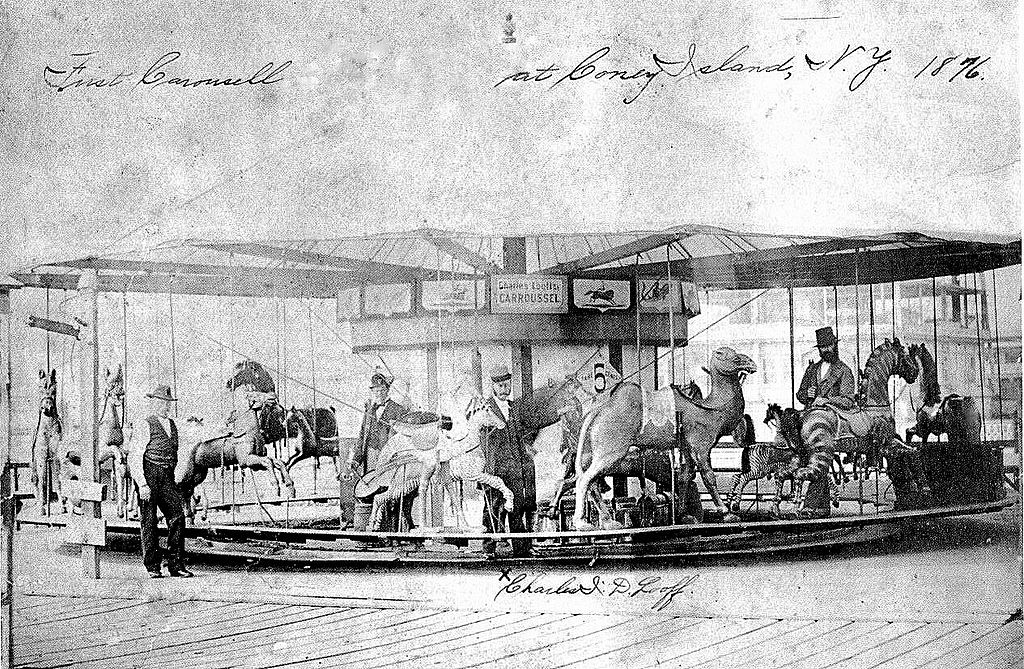

Entrepreneurs were quick to satisfy the public’s desire for fast-paced entertainment. During the 1890s, a series of popular amusement parks opened in Coney Island in New York. Unlike Central Park, Coney Island glorified adventure. It offered exotic, dreamlike landscapes and a loose, free social environment. At Coney Island men could remove their coats and ties and both sexes could enjoy rare personal freedom.

New York City’s Central Park was supposed to reinforce self-control and delayed gratification. Coney Island was a consumer’s world of extravagance, gaiety, abandon, revelry, and instant gratification. It attracted working-class Americans who longed for a taste of the good life. If a person could never hope to own a mansion in Newport, Rhode Island, he or she could for a few dimes experience the exotic pleasures of Luna Park or Dreamland Park. Even the rides in the amusement park were designed to create illusions and break down reality. Mirrors distorted peoples’ images and rides threw them off balance. At Luna Park, the “Witching Waves ” simulated the bobbing of a ship at high sea, and the “Tickler” featured spinning circular cars that threw riders together.

In part, the desire for intense physical and emotional experience was met through sports, athletics, and out-of-door activities. But its primary outlet was vicarious—through mass culture. Craving more intense experience, eager to break free of the confining boundaries of genteel culture, Americans turned to new kinds of newspapers and magazines and new forms of commercial entertainment.