Politics during the Gilded Age

Government Retrenchment and Government Corruption

In recent years, politicians from both parties have called for efforts to eliminate wasteful government expenditures and to balance the federal budgets. During the late 1870s and 1880s, retrenchment was a very serious matter, especially in the South. Salaries of many government officials were slashed dramatically. Some Southern states reduced officials’ salaries by half. To discourage its legislature from remaining in session too long, Texas cut the pay of legislators from five to two dollars a day if they met for more than sixty days every two years.

Ironically, the attempts to scale back government spending coincided with a spectacular wave of government corruption. Iowa built a new state capitol only to find out that its foundation stones had cracked and had to be replaced. New York spent $13 million on a county court house, including $100,000 on a table and chairs. In Louisiana, a state treasurer was accused of stealing $777,000. His counterpart in Tennessee was accused of taking $400,000. One Republican Senator, Joseph Foraker, received more than $44,000 in “lobbying fees” in a single year from John D. Rockefeller.

Misconceptions about the Gilded Age

In recent years, it has become commonplace to characterize politics in the Gilded Age as corrupt and issueless. The major parties “divided over spoils, not issues” and over “patronage, not principle,” in the words of the historian Richard Hofstadter, and maintained voter loyalty by waving the bloody shirt (i.e., appealing to Civil War loyalties) and playing on religious, ethnic, and regional divisions.

This view is quite misleading. An era of intense partisan fervor, the Gilded Age had a higher level of voter turnout than at any other time in American history. The federal government assumed greater authority and power over banking and currencies, taxes and tariffs, land and immigration. This period also witnessed the rise of a number of highly politicized movements—including the temperance and women’s rights crusades and the Populist insurgency among Southern and Western farmers —that sought to address the wrenching social transformations of the age.

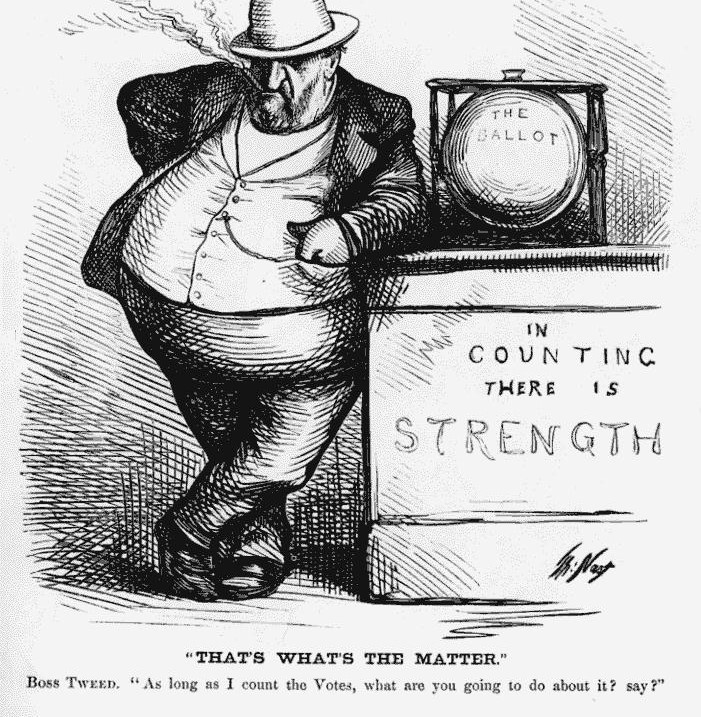

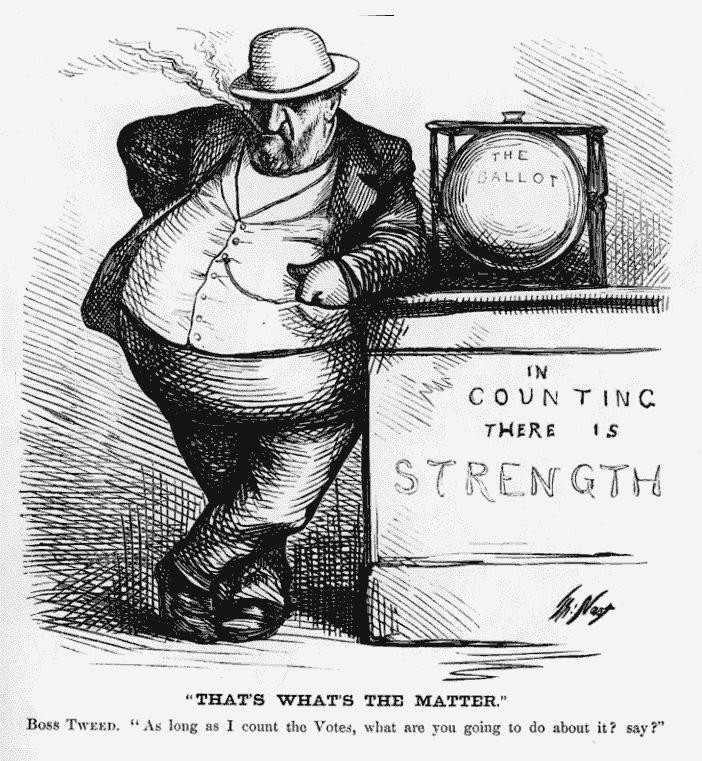

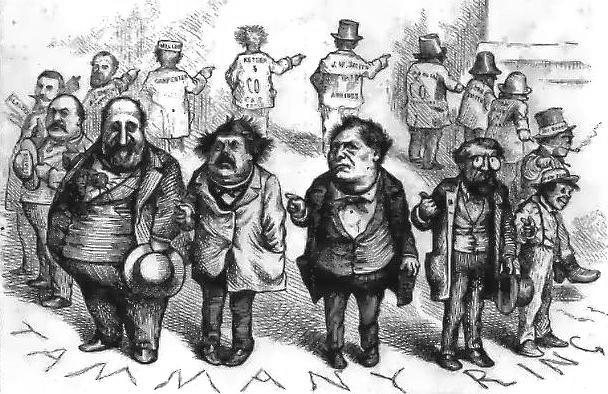

Boss Tweed

To many late nineteenth century Americans, he personified public corruption. In the late 1860s, William M. Tweed was the political boss of New York City. His headquarters, located on East 14th Street, was known as Tammany Hall. He wore a diamond, orchestrated elections, controlled the city’s mayor, and rewarded political supporters. His primary source of funds came from the bribes and kickbacks that he demanded in exchange for city contracts. The most notorious example of urban corruption was the construction of the New York County Courthouse, begun in 1861 on the site of a former almshouse. Officially, the city wound up spending nearly $13 million—roughly $178 million in today’s dollars—on a building that should have cost several times less. Its construction cost nearly twice as much as the purchase of Alaska in 1867.

The corruption was breathtaking in its breadth and baldness. A carpenter was paid $360,751 (roughly $4.9 million today) for one month’s labor in a building with very little woodwork. A furniture contractor received $179,729 ($2.5 million today) for three tables and 40 chairs. And the plasterer, a Tammany functionary, Andrew J. Garvey, got $133,187 ($1.82 million now) for two days’ work; his business acumen earned him the sobriquet “The Prince of Plasterers.” Tweed personally profited from a financial interest in a Massachusetts quarry that provided the courthouse’s marble. When a committee investigated why it took so long to build the courthouse, it spent $7,718 ($105,000) to print its report. The printing company was owned by Tweed.

In July 1871, two low-level city officials with a grudge against the Tweed Ring provided The New York Times with reams of documentation that detailed the corruption at the courthouse and other city projects. The newspaper published a string of articles. Those articles, coupled with the political cartoons of Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly, created a national outcry, and soon Tweed and many of his cronies were facing criminal charges and political oblivion. Tweed died in prison in 1878.

The Tweed courthouse was not completed until 1880, two decades after ground was broken. By then, the courthouse had become a symbol of public corruption. “The whole atmosphere is corrupt,” said a reformer from the time. “You look up at its ceilings and find gaudy decorations; you wonder which is the greatest, the vulgarity or the corruptness of the place.”

Boss rule, machine politics, payoffs and graft, and the spoils system outraged late nineteenth-century reformers. But were bosses and political machines as corrupt as their critics charged?

George Washington Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, New York’s Democratic political machine, distinguished between “honest” and “dishonest” graft. Dishonest graft involved payoffs for protecting gambling and prostitution. Honest graft might involve buying up land scheduled for purchase by government. As Plunkitt said, “I seen my opportunities and I took ’em.”

Paradoxically, a political machine often created benefits for the city. Many machines professionalized urban police forces and instituted the first housing regulations. Political bosses served the welfare needs of immigrants. They offered jobs, food, fuel, and clothing to the new immigrants and the destitute poor. Political machines also served as a ladder of social mobility for ethnic groups blocked from other means of rising in society.

In The Shame of the Cities, the muckraking journalist, Lincoln Steffens, argued that it was greedy businessmen who kept the political machines functioning. It was their hunger for government contracts, franchises, charters, and special privileges, he believed, that corrupted urban politics.

At the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, urban reformers would seek to redeem the city through beautification campaigns, city planning, rationalization of city government, and increases in city services.

Civil Service Reform

George Plunkitt, a local leader of New York City’s Democratic Party, defended the spoils system. “You can’t keep an organization together without patronage,” he declared. “Men ain’t in politics for nothin’. They want to get somethin’ out of it.”

But in one of the most significant political reforms of the late nineteenth century, Congress adopted the Pendleton Act, creating a federal civil service system, partly eliminating political patronage.

Andrew Jackson introduced the spoils system to the federal government. The practice, epitomized by the saying “to the victory belong the spoils,” involved placing party supporters into government positions. An incoming president would dismiss thousands of government workers and replace them with members of his own party. Scandals under the Grant administration generated a mounting demand for reform.

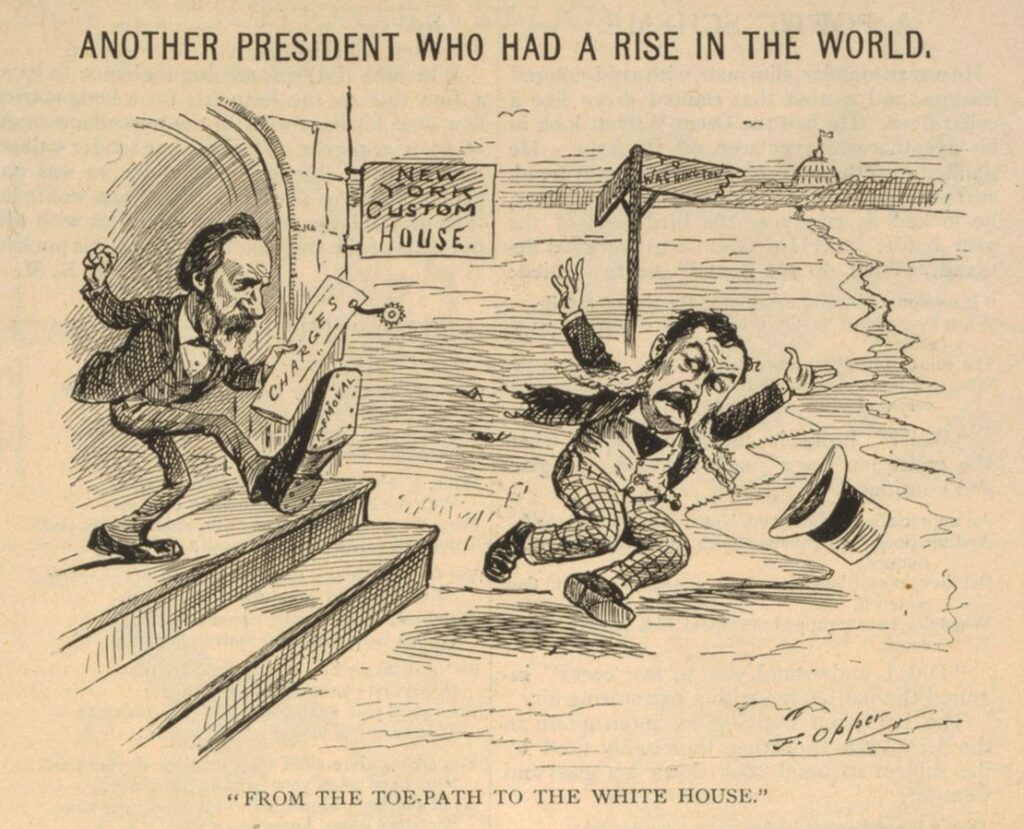

Ironically, the president who led the successful campaign for civil service, Chester Arthur, a Republican, was linked to a party faction from New York that was known for its abuse of the spoils of office. In fact, in 1878, Arthur had been fired from his post at New York Federal Custom’s Collection for giving away too many patronage jobs.

In 1880, Arthur had been elected vice president on a ticket headed by James A. Garfield. Garfield’s assassination in 1881 by a mentally disturbed man, Charles J. Guiteau, who thought he deserved appointment to a government job, led to a public outcry for reform.

As president, Arthur became an ardent reformer. He insisted that high ranking members of his own party be prosecuted for their part in a Post Office scandal. He vetoed a law to improve rivers and harbors. In 1883, he helped push through the Pendleton Act. Failing to please either machine politicians or reformers, Arthur was the last incumbent president to be denied renomination for a second term by his own party.

The Pendleton Act stipulated that government jobs should be awarded on the basis of merit. It provided for selection of government employees through competitive examinations. It also made it unlawful to fire or demote covered employees for political reasons or to require them to give political service or payment, and it set up a Civil Service Commission to enforce the law.

When the Pendleton Act went into effect, only ten percent of the government’s 132,000 civilian employees were placed under civil service protections.The rest remained at the disposal of the party power, which could distribute jobs for patronage, payoffs, or purchase. Today, more than ninety percent of the 2.7 million federal civilian employees are covered by merit systems.

In 1884, New York became the first state to adopt a civil service system for state workers. Massachusetts became the second state when it started a merit system in 1885.

History Through…

…Political Cartoons: Thomas Nast

He was the most famous political cartoonist ever. He played a central role in bringing down the Tammany Hall regime of “Boss” William M. Tweed, an enduring symbol of big-city corruption. He popularized the elephant and donkey as the symbols of the Republican and Democratic parties; and his drawings of Christmas scenes and Santa Claus shaped the popular image of the holiday. He was also a powerful voice for the rights of African Americans.

Born in Bavaria in 1840, he migrated to the United States at the age of nine and was a newspaper cartoonist at the age of sixteen.

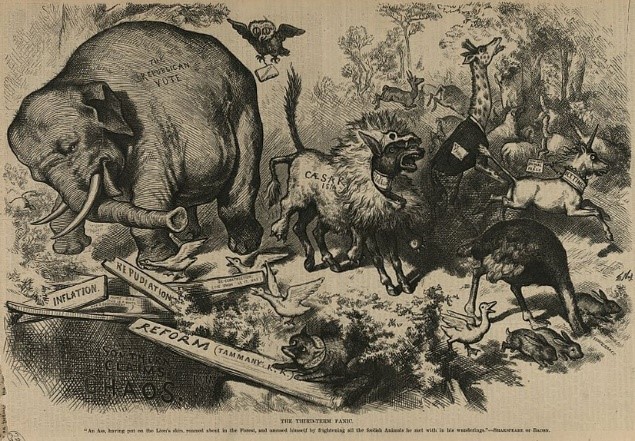

He made the donkey and the elephant the popular symbols of the Democratic and Republican Party in an 1874 cartoon. In the cartoon, a donkey is wearing a lion’s skin and scaring all the other animals in the forest, including the Republican lion.

He was largely responsible for the image of a jolly, rotund bearded Santa Claus.

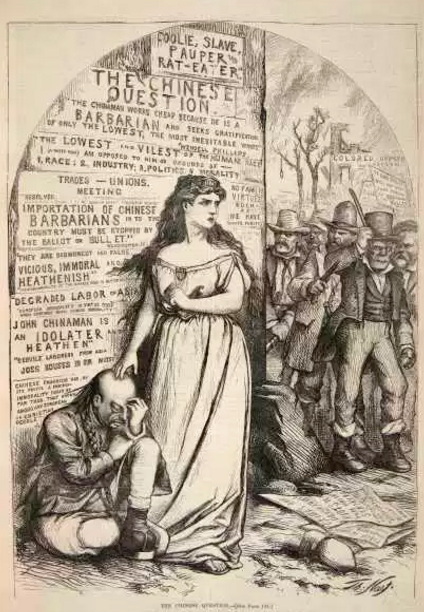

In his cartoon on “The Chinese Question”, he protested discrimination against Chinese immigrants.

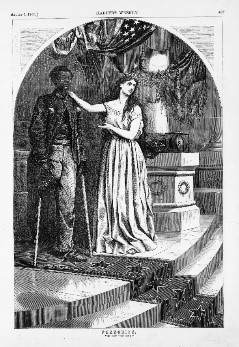

In this cartoon entitled “Franchise”, he reminded viewers of African American soldiers’ pivotal role in the defeat of the Confederacy.

Tweedledum and Tweedledee

During the 1870s and 1880s, the Democratic and Republican Parties were of almost exactly equal strength. In the presidential elections between 1876 and 1892, no more than 3.1 percentage points separated the two parties.

In the late nineteenth century, it was sometimes said that there was not a dime’s difference between the two parties, that the difference between the two parties was the difference between tweedledum and tweedledee. This was not true. The parties differed dramatically in their principles, programs, and ethno-cultural composition.

The Republican Party tended to emphasize national unity, economic modernization, and moral reform. Regarding the Democrats as the party of treason for opposing the Civil War, the Republicans ran Union veterans in eight of nine presidential elections between 1868 and 1900. The sole exception, James G. Blaine, lost in 1884. The party urged the faithful to “vote as you shot.” They portrayed Democrats as “the old slave-owner and slave driver, the saloon-keeper, the ballot-box-stuffer, the Kuklux [Klan member], the criminal class of the great cities, the men who cannot read or write.”

The Republicans were committed to rapidly modernizing the economy through such measures as protective tariffs to assist industry and land grants to encourage railroad construction. The Republican Party was also committed to using the Fourteenth Amendment to protect corporations’ ability to operate free from excessive state regulation.

The Democrats were split on this program of economic modernization. Grover Cleveland supported big business and the gold standard but in 1887 came out strongly against the tariff, which he viewed as a tax on consumers for the benefit of rich industrialists.

The Election of 1884

The presidential campaign of 1884 was one of the most memorable in American history. The Republican nominee, James G. Blaine of Maine, was nicknamed the “plumed knight,” but disgruntled Republican reformers regarded him as a symbol of corruption. He “wallowed in spoils like a rhinoceros in an African pool,” a critic declared.

These liberal Republicans indicated to Democratic leaders that they would bolt their own party and support a Democrat, provided he was a decent and honorable man. Grover Cleveland seemed to meet these qualifications. He had started his career as sheriff of Erie County where he personally hanged two murderers to spare the sensitivities of his subordinates. He had been known as the “veto” Mayor of Buffalo for rejecting political graft, and as governor he repudiated Tammany Hall.

Republicans waved the “bloody flag,” harshly attacking Cleveland for avoiding service during the Civil War. He had hired a substitute to take his place.

Democrats, in turn, claimed that Blaine had sold his influence in Congress to business interests. They published letters from a Boston bookkeeper which indicated that Blaine had personally benefited from helping a railroad keep a land grant. Democrats chanted: “Blaine! Blaine! James G. Blaine! The Continental Liar from the State of Maine!”

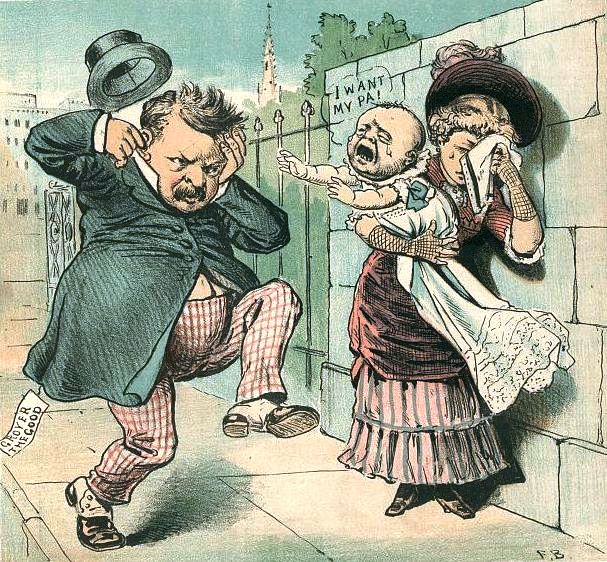

Then a Buffalo newspaper dealt Cleveland a devastating blow. Under the headline, “A Terrible Tale,” the newspaper revealed that the Democratic candidate had a child out of wedlock. Even worse, Republicans charged, Cleveland had placed the child in an orphanage and the mother in an insane asylum, Republicans wore white ribbons and campaigned under the phrase “home protection.”

But these moralistic attacks failed to ignite much public indignation against Cleveland. Republicans chanted, “Ma, ma, where’s my pa?” Democrats replied: “Gone to the White House, ha, ha, ha.”

Just six days before the election, a group of Protestant clergy were meeting in New York. The clergymen endorsed James Blaine with words that would alter the course of the election:

We are Republicans and don’t propose to leave our party and identify ourselves with the party whose antecedents are Rum, Romanism and Rebellion.

The following Sunday, as Irish Americans filed out of Catholic Churches, they were handed bills containing the phrase “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion,” attributed to Blaine himself. Blaine’s denials were ineffective and he lost New York by 1,149 votes. In the election, white Southerners, Irish Americans, and German American voters turned out in record numbers.

In office, Cleveland pleased conservatives by advocating sound money and reduction of inflation, curbing party patronage, and vetoing government pensions. But he alienated business and labor interests by proposing a lower tariff and was defeated by Republican Benjamin Harrison in 1888, winning the popular vote but losing the electoral vote.

In 1892, Cleveland won reelection thanks in part to a third party movement—the Populists—that siphoned off some of the strength of the Republican Party, and by a vigorous campaign against the extravagance of the Republican “Billion Dollar Congress.”

But his second term was ruined by the economic depression of the mid-1890s, the worst economic crisis that the country had ever seen. Insisting on sound money, he sought to keep the country on the gold standard and helped convince Congress to enact an income tax (which was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court). In 1896, Cleveland’s policies were repudiated by his own party.

Anti-Trust

The 1880s marked the emergence of trusts, companies that bought out locally-owned factories and merged them into conglomerates that sought to monopolize entire industries. The concentration of industry aroused “deep feelings of unrest,” said Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan, a conservative Republican:

The conviction was universal that the country was in real danger from another form of slavery…that would result from the aggregation of capital in the hands of a few individuals controlling, for their own profit and advantage exclusively, the entire business of the country.

A national consensus emerged that monopolies were dangerous to democracy. The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which applied only to railroads passing through more than one state, declared that railroads could only charge just and reasonable rates. It required railroads to post their rates, provide ten-day notice before raising rates, and prohibited railroads from charging less for a long haul than a short haul over the same line. The act also set up the first federal regulatory commission, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which had authority to investigate the railroads. However, railroad operators found ways to circumvent the law, and many of the ICC’s decisions were reversed by the Supreme Court.

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act passed in 1890 outlawed any combination “in restraint of trade.” In 1894, in the case of U.S. v. Debs, the Supreme Court ruled that the act could be used to stop labor unions from interfering with commerce. Between 1890 and 1901, the federal government filed eighteen suits under the law, four against labor unions.

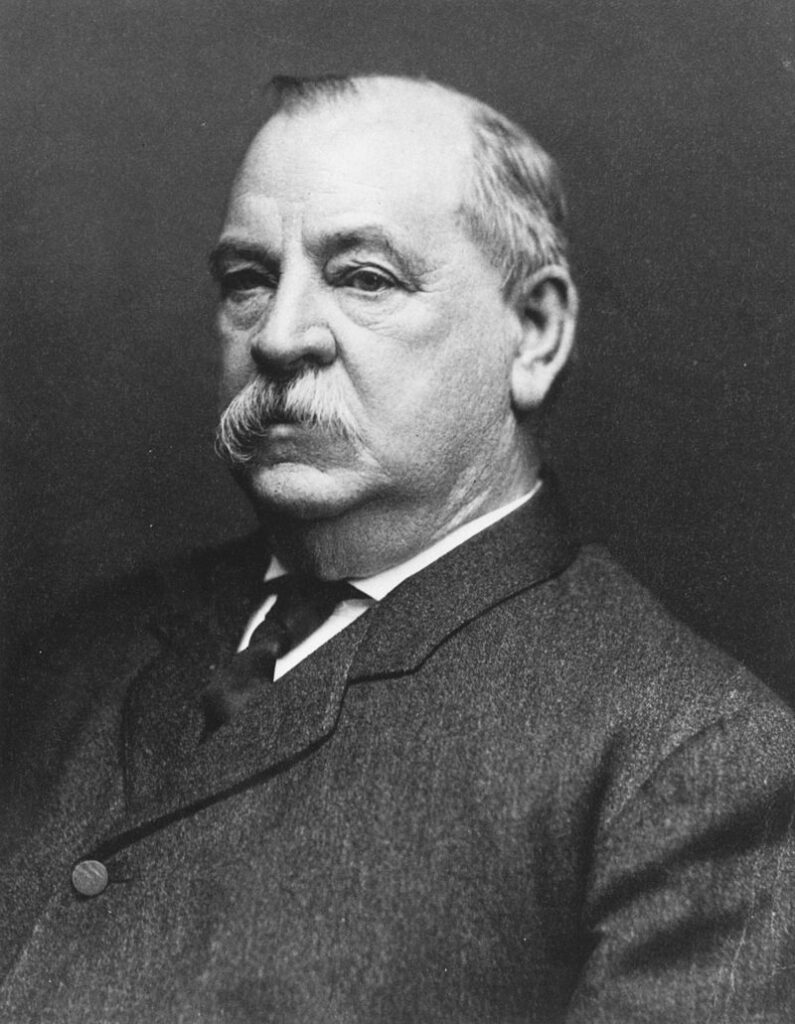

Grover Cleveland

He was the first Democratic president elected after the Civil War and the only person ever to be elected to non-consecutive terms in office. A bachelor when he was elected to his first term, he became the first president to be married in the White House when he wed Frances Folsom, a former ward twenty-seven years his junior. He became the first president to have children while in office. The Baby Ruth candy bar was named after one of his offspring.

When confronted with a charge that he had fathered a child out of wedlock, Cleveland immediately acknowledged the truth. He also admitted that he had avoided military service in the Civil War by paying a substitute to take his place.

When warned that his fight for lower tariffs might cost him the 1888 election, he replied: “What is the use of being elected or re-elected unless you stand for something.” Cleveland was defeated by Benjamin Harrison in the Electoral College even though he won the popular count by more than 90,000 votes. He lost the election because he failed to carry his home state of New York.

In 1892, his supporters urged him to seek accommodations with western Democrats who wanted unlimited coinage of silver. His response was, “I am supposed to be the leader of my party. If any word of mine can check these dangerous fallacies, it is my duty to give that word, whatever the cost may be to me.”

As president, he signed the Dawes Act, which distributed Indians’ tribal lands to individual families, established the Departments of Agriculture and of Labor, lowered tariffs, and successfully defended the gold standard.