The Plight of Farmers and the Rise of Populism

The Farmers’ Plight

At the end of the nineteenth century, about a third of Americans worked in agriculture, compared to only about four percent today. After the Civil War, drought, plagues of grasshoppers, boll weevils, rising costs, falling prices, and high interest rates made it increasingly difficult to make a living as a farmer. In the South, one-third of all landholdings were operated by tenants. Approximately seventy-five percent of African American farmers and twenty-five percent of white farmers tilled land owned by someone else.

Every year, the prices farmers received for their crops seemed to fall. Corn fell from 41 cents a bushel in 1874 to thirty cents by 1897. Farmers made less money planting 24 million acres of cotton in 1894 than they did planting nine million acres in 1873. Facing high interest rates of upwards of ten percent a year, many farmers found it impossible to pay off their debts. Farmers who could afford to mechanize their operations and purchase additional land could successfully compete, but smaller, more poorly financed farmers, working on small plots marginal land, struggled to survive.

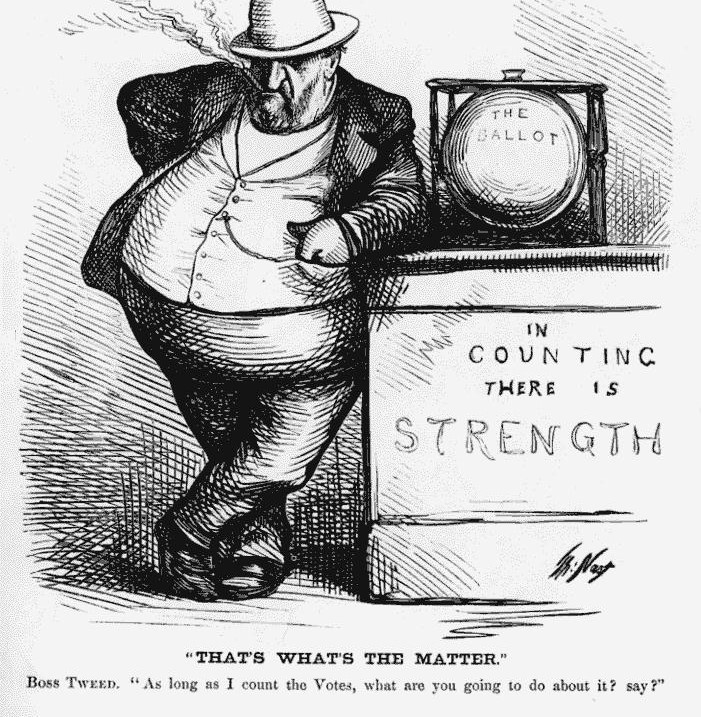

Many farmers blamed railroad owners, grain elevator operators, land monopolists, commodity futures dealers, mortgage companies, merchants, bankers, and manufacturers of farm equipment for their plight. Many attributed their problems to discriminatory railroad rates, monopoly prices charged for farm machinery and fertilizer, an oppressively high tariff, an unfair tax structure, an inflexible banking system, political corruption, and corporations that bought up huge tracks of land. They considered themselves to be subservient to the industrial Northeast, where three-quarters of the nation’s industry was located. They criticized a deflationary monetary policy based on the gold standard that benefited bankers and other creditors.

All of these problems were compounded by the fact that increasing productivity in agriculture led to price declines. In the 1870s, 190 million new acres were put under cultivation. By 1880, settlement was moving into the semi-arid plains. At the same time, transportation improvements meant that American farmers faced competitors from Egypt to Australia in the struggle for markets.

The first major rural protest was the Patrons of Husbandry, which was founded in 1867 and had 1.5 million members by 1875. Known as the Granger Movement, these embattled farmers formed buying and selling cooperatives and demanded state regulation of railroad rates and grain elevator fees.

Early in the 1870s the Greenback Party agitated for the issue of paper money, not backed by gold or silver, with the idea that a depreciating currency would make it easier for debtors to meet their obligations.

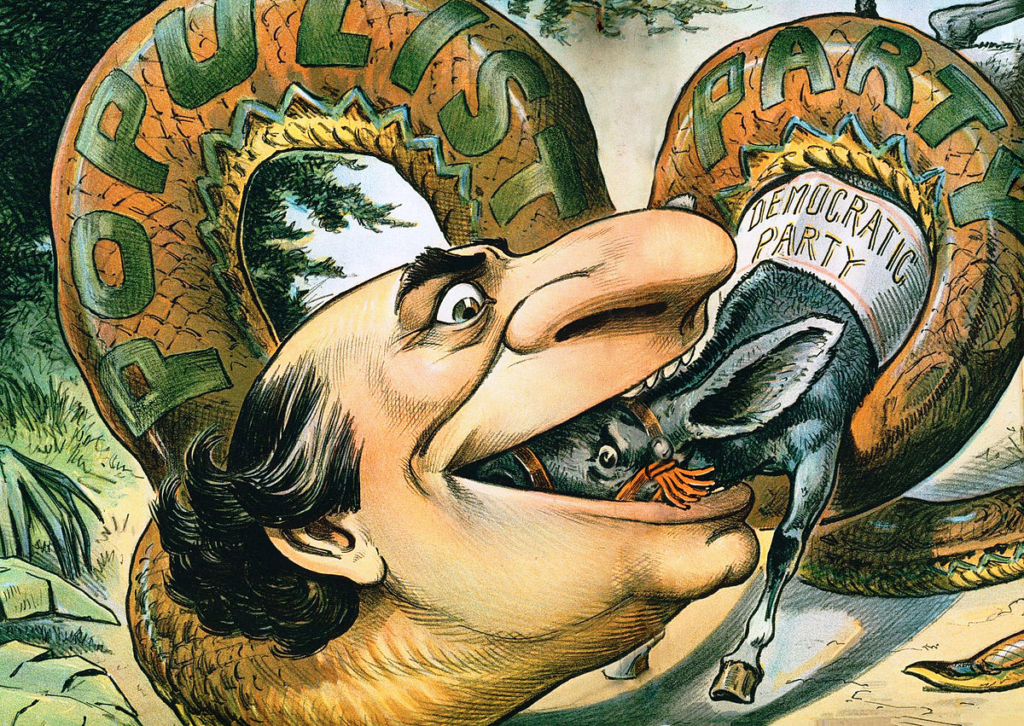

Another wave of protest grew out of the National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union (the Southern Farmers Alliance) formed in Lampasas County, Texas in 1875, and the Northwestern Farmers’ Alliance, founded in Chicago in 1880. By the late 1880s, the cooperative business enterprises set up by the Farmers’ Alliances had begun to fail due to inadequate capitalization and mismanagement. By 1890, the Farmers Alliances had begun to enter politics. In 1892 the Alliance formed the Peoples’ or Populist Party. Among other things, the Populists called for a federally-financed commodity credit system that would have allowed farmers to store their crop in a federal warehouse to await favorable market prices and meanwhile borrow up to eighty percent of the current market price.

The Populist platform also sought a graduated income tax, public ownership of utilities, the voter initiative and referendum, the eight-hour workday, direct election of U.S. Senators, immigration restrictions, and government control of the currency.

In the presidential election of 1892, the Populist candidate, James B. Weaver of Iowa, received more than a million popular votes (8.5 percent of the total) and 22 electoral votes. The Populists also elected ten representatives, five senators, and four governors, as well as 345 state legislators.

Populism

A little more than a century ago, a grassroots political movement arose among small farmers in the country’s wheat, corn, and cotton fields to fight banks, big corporations, railroads, and other “monied interests.” The movement burned brightly from 1889 to 1896, before fading out. Nevertheless, this movement fundamentally changed American politics.

The Populist movement grew out of earlier movements that had emerged among southern and western farmers, such as the Grangers, the Greenbackers, and the Northern, Southern, and Colored Farmers Alliances. As early as the 1870s, some farmers had begun to demand lower railroad rates. They also argued that business and the wealthy—and not land—should bear the burden of taxation.

Populists were especially concerned about the high cost of money. Farmers required capital to purchase agricultural equipment and land. They needed credit to buy supplies and to store their crops in grain elevators and warehouses. At the time, loans for the supplies to raise a crop ranged from 40 percent to 345 percent a year. The Populists asked why there was no more money in circulation in the United States in 1890 than in 1865, when the economy was far smaller, and why New York bankers controlled the nation’s money supply.

After nearly two decades of falling crop prices, and angered by the unresponsiveness of two political parties they regarded as corrupt, dirt farmers rebelled. In 1891, a Kansas lawyer named David Overmeyer called these rebels Populists. They formed a third national political party and rallied behind leaders like Mary Lease, who said that farmers should raise more hell and less corn. The Populists spread their message from 150 newspapers in Kansas alone.

Populist leaders called on the people to rise up, seize the reins of government, and tame the power of the wealthy and privileged. Populist orators venerated farmers and laborers as the true producers of wealth and reviled blood-sucking plutocrats. Tom Watson of Georgia accused the Democrats of sacrificing “the liberty and prosperity of the country…to Plutocratic greed,” and the Republicans of doing the wishes of “monopolists, gamblers, gigantic corporations, bondholders, [and] bankers.” The Populists accused big business of corrupting democracy and said that businessmen had little concern for the average American “except as raw material served up for the twin gods of production and profit.” The Populists also blamed a protective tariff for raising prices by keeping affordable foreign goods out of the country.

The party’s platform endorsed labor unions, decried long work hours, and championed the graduated income tax as a way to redistribute wealth from business to farmers and laborers. The party also called for an end to court injunctions against labor unions. “The fruits of the toil of millions,” the Party declared in 1892, “are boldly stolen to build up the fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind.” In addition, the Populists called for a secret ballot; women’s suffrage; an eight-hour workday, direct election of U.S. Senators and the President and Vice President; and initiative and recall to enable voters to prpose legislation and remove public official from office make the political system more responsive to the people.

The party put aside moral issues like prohibition in order to focus on economic issues. “The issue,” said one Populist, “is not whether a man shall be permitted to drink but whether he shall have a home to go home to, drunk or sober.” A significant number of Populists were also willing to overcome racial divisions. As one leader put it, “The problem is poverty, not race.”

The Populists embraced government regulation to get out from the domination of unregulated big business. The platform demanded government ownership of railroads, natural resources, and telephone and telegraph systems. Even more radically, some Populists called for a coalition of poor white and poor black farmers and for an alliance of farmers and urban workers.

Populism had an unsavory side. The Populists had a tendency toward paranoia and overblown rhetoric. They considered Wall Street an enemy. Many Populists were hostile toward foreigners and saw sinister plots against liberty and opportunity. The party’s 1892 platform described “a vast conspiracy against mankind has been organized on two continents and is rapidly taking possession of the world.” After their crusade failed, the embittered Georgia Populist Tom Watson denounced Jews, Catholics, and African Americans with the same heated rhetoric he once reserved for “plutocrats.”

But in the early twentieth century, many of the Populist proposals would be enacted into law, including the secret ballot; women’s suffrage; the initiative, referendum, and recall; a Federal Reserve System; farm cooperatives, government warehouses; railroad regulation; direct election of U.S. Senators; and conservation of public lands.

The Populists also provided the inspiration for later grassroots movements, including the Anti-Saloon League, which helped make Prohibition a part of the Constitution; and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which persuaded millions of auto workers, stevedores, and steel workers to unionize with its call for industrial democracy.

Populist rhetoric still plays an important role in contemporary American politics. Politicians speak the language of populism whenever they defend ordinary people against entrenched elites and a government dominated by special interests. During the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt hailed “the forgotten man” and railed against “economic royalists” and in 1992 Bill Clinton ran for the presidency by pledging to “put people first.”

Currently, the term “populism” is used to refer to anyone who claims to speak for ordinary women and men. But when the word first appeared at the end of the nineteenth century, it applied to those who wished to use the government to curb the power of economic elites and chart a more egalitarian path of economic development.

The Election of 1896

Not since the election of 1860 were political passions so deeply stirred. At stake appeared to be two very different visions of what kind of society America was to become.

Rarely in American history had conditions seemed so unsettled. The financial panic of 1893 was followed by four years of high unemployment and business bankruptcies. The panic led Jacob Coxey, a businessman from Massillon, Ohio, to organize the first mass march on Washington. Coxey’s army demanded a federal public works program. As rumors of revolution swept Washington, the government responded by jailing the march’s leaders.

The violent steel strike at Homestead mills near Pittsburgh in 1892 and the intervention of federal troops in the Pullman Strike and the imprisonment of labor leader Eugene V. Debs in 1894 stirred the public passions. By 1896, the situation of many southern and western farmers was desperate.

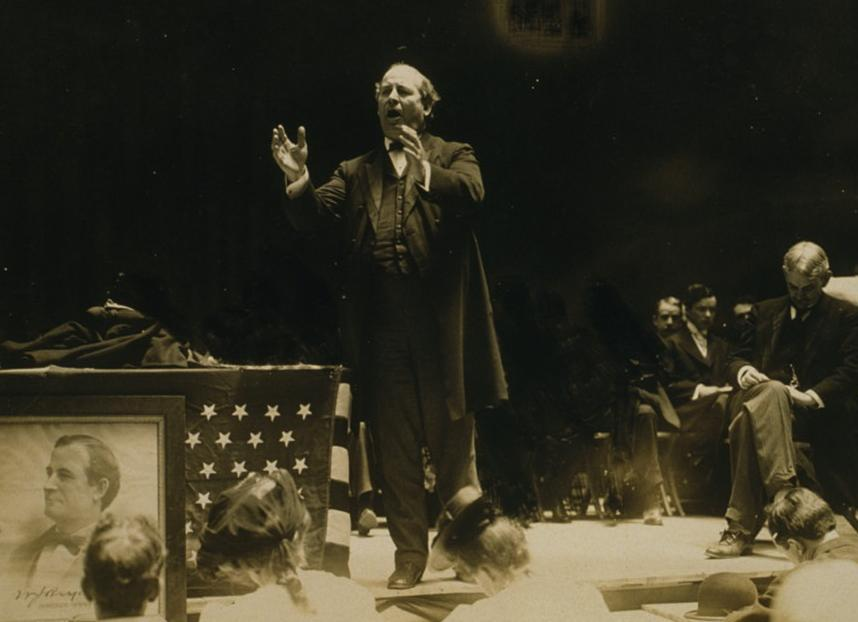

At the Democratic Party convention in Chicago, delegates repudiated the leadership of President Grover Cleveland, seized the Free Silver issue from the Populists, and nominated William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska. Bryan won his party’s nomination with one of the most famous speeches ever delivered at a political convention. “The boy orator of the Platte” was viewed by his supporters as the champion of the plain people, the prairie avenger who promised financial relief to hard-pressed farmers. Bryan’s supporters viewed his campaign as a continuation of the old American struggle between producers and exploiters, debtors and creditors. To hard-pressed farmers, Bryan’s program of financial relief offered hope that they might survive financially.

Bryan’s radical attacks on Wall Street, banks, and railroads frightened many prosperous farmers and businessmen. The gulf between populist farmers and immigrant and urban laborers made it impossible for the Populists to forge successful ties with the urban working class. The Populist movement was deeply imbued with the values of Evangelical Protestantism, alienating many Catholics.

Bryan’s opponent, Republican William McKinley, campaigned on a platform of jobs and sound money, promising a “full dinner pail.”

Business interests spent nearly $16 million to elect McKinley, allowing the Republicans to adopt a new style of campaigning. Instead of relying on party organization to turn out the vote, Republicans relied increasingly on advertisements.

Unlike some earlier Republican candidates, McKinley rejected moralistic crusades, like prohibition, that alienated ethnic groups. In 1896, McKinley assembled a political coalition that included both the new industrialists and their workers. Most of industrial America voted Republican, including most workers in factories, mines, mills, and railroads. As a result, the Republican Party went on to dominate the presidency for most of the next three decades.

During the late 1890s, two solutions appeared to the nation’s monetary problems. New discoveries of gold in South Africa and Australia greatly increased the world’s gold supply. At the same time, bankers created a new “currency”—bank checks. More and more of the nation’s business transactions took place through checks rather than through paper money and gold coins.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Is The Wizard of Oz just a fairy tale about a girl from Kansas transported to a colorful land of witches and munchkins? Or does the story have a political dimension? Scholars still disagree about whether L. Frank Baum’s great children’s story was about the collapse of the Populist movement.

Henry Littlefield, a teacher in Pebble Beach, California, was the first person to suggest that the story was about Populism. He argued that:

- The Scarecrow (who has no brain) represented the farmers.

- The Tin Man (who had once been a human wood-cutter, but chopped his body parts off and replaced them with metal) represented industrial workers.

- The Cowardly Lion represented northern reformers.

- The Emerald City represented Wall Street, greenback colored.

- The Wizard represented the Money Power, whose influence rests on manipulation and illusion.

Littlefield interpreted the yellow brick road as representing gold and Dorothy’s silver slippers (which were changed in the movie to ruby slippers) as representing the Populist call for backing the dollar with silver. Oz was the abbreviation for ounces, a reference to the Populist call for the government to coin.

The Populist Crusade and Restrictions on African Americans

During the late 1880s and early 1890s, a million African Americans joined the Colored Farmers Alliance. At one of their conventions, black farmers argued that “land belongs to the sovereign people,” and should not be treated as private property. As the Populist movement divided the South’s white population, a number of black leaders saw a chance to forge an alliance with poorer whites.

The threat of this bi-racial alliance led many upper-class conservative Democrats to play the “race card.” They appealed to white farmers to vote Democratic in order to maintain a system of white supremacy.

The appeal to racism proved highly effective in undermining Populism’s appeal. Upper-class conservative Democrats took the lead in calling for legalized segregation and disfranchisement of African Americans. But the reforms they offered, such as the poll tax and literacy tests, had the practical effect of also taking the vote away from many poor whites.