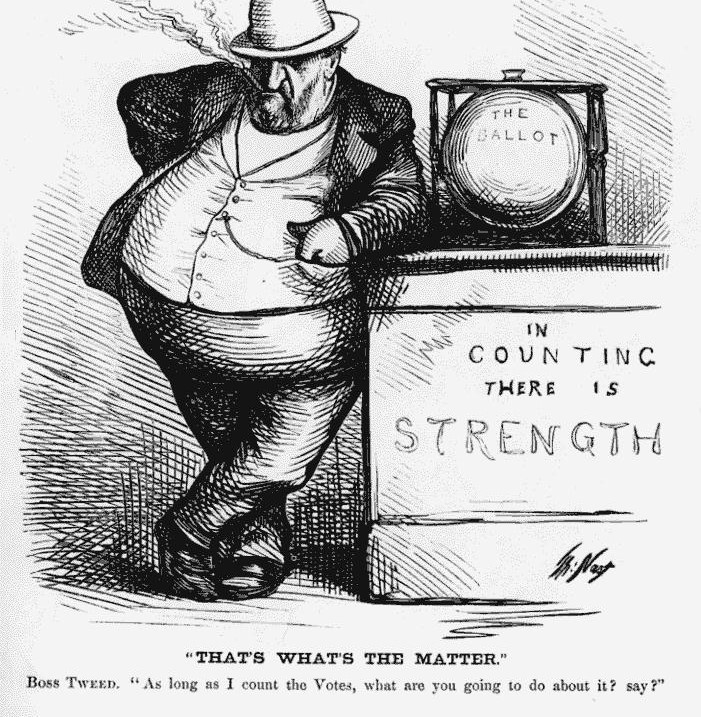

Political Alternatives

Socialist and Radical Alternatives

The rise of the American Federation of Labor did not spell the disappearance of more radical groups. Two organizations offered a more radical vision. The Industrial Workers of the World, formed in 1905, clamored for “one big union” to oust “the ruling class” and abolish the wage system.

The Socialist Party, founded in 1901, had, by 1912, grown to 118,000 members. By that year, it had elected 1,200 public officials, including the mayors of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Flint, Michigan, and Schenectady, New York. More than 300 Socialist periodicals appeared. A weekly socialist newspaper, the Appeal to Reason, reached a circulation of over 700,000 copies in 1913.

Socialist support was concentrated between two immigrant groups: Germans, who had left Europe in the 1840s, and East European Jews, who were refugees from Czarist repression. The largest daily socialist newspaper in the United States, the Jewish Daily Forward, which had a circulation of 142,000 in 1913, was published in Yiddish, not in English. The Socialist Party’s first major electoral victories occurred in Milwaukee, which had a large German community. In 1910, the city elected a Socialist mayor and member of Congress.

The Socialist Party declined in influence during Democratic President Woodrow Wilson’s first term, as many reforms enacted by Congress diminished the party’s appeal. Support for the party briefly surged during World War I, but had dissipated by 1919 as a result of federal, state, and local campaigns to suppress the party and internal disputes involving how the party should respond to the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia.

American Characters

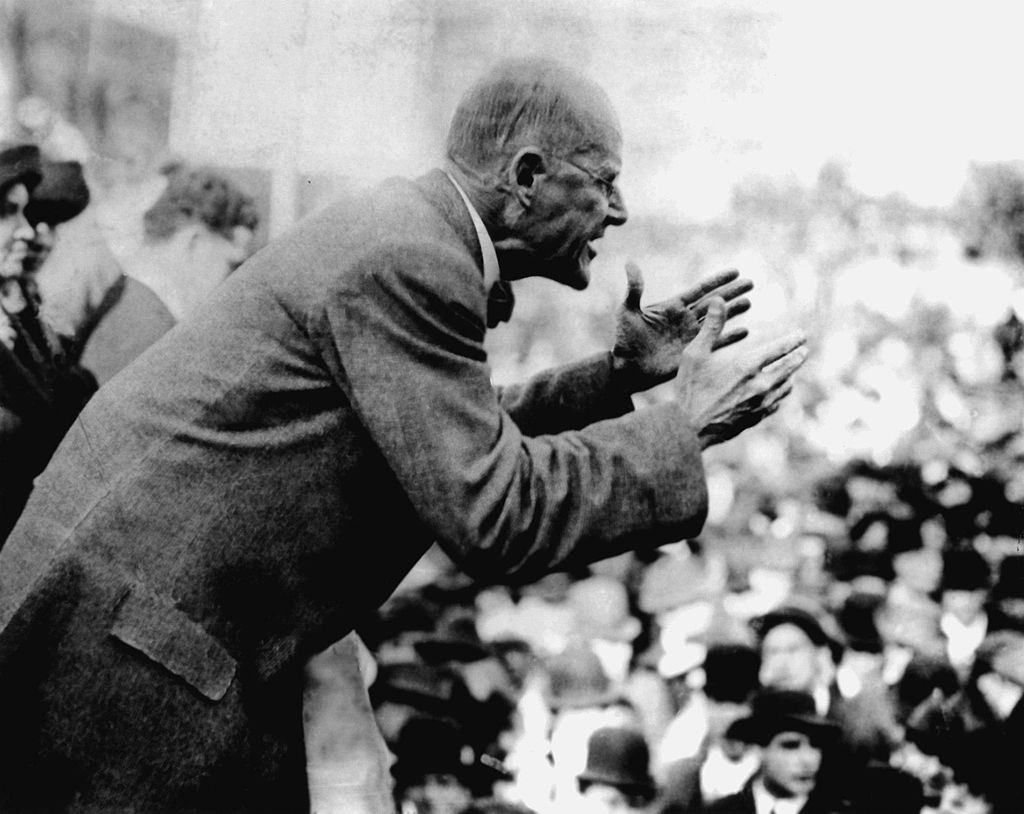

Eugene Debs

He led the drive for one big union embracing all rail workers. In his early twenties, he had become an official of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, a bastion of crafts separatism. He started out as a champion of compromise and arbitration as avenues to harmonious and equitable labor-management relations. But experience convinced him that the robber barons in command of major railroads were less interested in peace than in pitting one brotherhood against another. The collapse of a strike by rail switchmen in Buffalo in 1892 after the other crafts refused to come to their aid prompted Debs to resign his post with the firemen and become prime mover in setting up the American Railway Union, which cut across all craft lines and even took in longshoremen, car builders, and coal miners. The infant union had phenomenal growth, quickly eclipsing in size the combined membership of all the old-line brotherhoods. But its demise was equally swift.

Emma Goldman

She was synonymous with radicalism. Emma Goldman (1869-1940) was born in Russia and moved to the United States in 1886. She was soon caught up in a swirl of radical movements—feminism, birth control, pacifism, and anarchism. She defended free speech, free love, and the rights of striking workers and homosexuals.

At the height of the Red Scare in 1919, Emma Goldman was imprisoned on Ellis Island, put on a ship with 246 men and two other women who were branded radicals, and deported to the Soviet Union. The roundup was engineered by J. Edgar Hoover, then head of the Justice Department’s Radical Division and later director of the FBI.

Greeted by the wife of the famous writer Maxim Gorky, Emma Goldman said: “This is the greatest day in my life. I once found political freedom in America. Now the doors are closed to free thinkers, and the enemies of capitalism find once more sanctuary in Russia.” But her enthusiasm for the new Soviet Union quickly faded. She lived there for less than two years. In a book describing her time in Russia, she argued that repression and terror were the inevitable result of Bolshevik ideology. In exile, she lived in France. During the Spanish Civil War, she worked with anarchists in defense of the Spanish Republic.

Mother Jones

Mary Harris “Mother” Jones was a legendary union organizer and strike leader. Born in Ireland in 1830, she migrated to the United States at the age of eight, and died in 1930. During her long life, she taught school, worked as a seamstress, survived a yellow fever epidemic that killed her husband and their four children, and watched her house and business burn in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. She was present at many of the most famous American strikes, exhorting workers in coal strikes in Colorado, Illinois, and West Virginia, steel strikes in Indiana and Pennsylvania, and cotton mill strikes in Alabama. She was present at the convention that founded the radical Industrial Workers of the World. She said, “If I pray I will have to wait until I am dead to get anything; but when I swear I get things here.”

Podcast

“Why Did the Socialist Movement Fail in the U.S.” Podcast

Listen to the podcast “Why Did the Socialist Movement Fail in the U.S.”