Overview: The Gilded Age

A Distant Mirror

In the 1870s, a woman named Myra Bradwell did a most unladylike thing. She applied for a license to practice law. A Vermont native, she had moved to Illinois in the mid-1850s, and after the ratification in 1868 of the 14th Amendment, which guaranteed all citizens equal protection of the law, she sued to become an attorney. After the Illinois courts rejected her petition, she turned to the U.S. Supreme Court, which, in April 1873, said it was within the power of Illinois to limit membership in the bar to men only. Only one Justice dissented. One Justice wrote:

“Man is, or should be, woman’s protector of defender. The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life…. The paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfill the benign offices of wife and mother. This is the law of the Creator. And the rules of civil society must be adapted to the general constitution of things, and cannot be based on exceptional cases.”

At first glance, late nineteenth century America might seem remote and even irrelevant. It was a society without Social Security, Medicare, health insurance, and government regulation, not to mention airplanes, antibiotics, automobiles, computers, radio, and television. The telephone had been invented, but in 1877 there were only nine in the entire country.

The government was tiny. In 1877, there were only about 100,000 federal employees, and only 22,000 if the military and post office were excluded. There was no civil service system and no income tax. Government revenues were mainly raised through taxes on imports, tobacco, and alcohol.

It was a small, predominantly rural society. In 1877, the country’s total population was just 47 million, just a sixth of what it is today. Only one city had more than a million people and just three others had as many as half a million.

Today, our birth rate is around the replacement level, but in 1877, fifteen percent of married women had ten or more children, and another twenty-two percent had between seven and nine. As a result of the high birth rate, the population was very young. Half the population was twenty or younger; today the average American is over thirty.

Perhaps most striking to us was the lack of formal education. Only about three in five children attended school in a typical year, and they only attended about eighty days a year, compared to 180 today. Most left school in their early teens. Only about two-and-a-half percent of the school-aged population graduated from high school. Advanced degrees beyond college were almost unheard of. In 1877, only one Master’s degree was conferred in the whole country.

The other startling fact was how poor the average family was. The average income of an urban family in 1877 was $738, and two-thirds of that was spent on food and heating. After clothing and housing were paid for, there was just forty-four dollars left over, to save for old age or to buy a house, to pay for medical care or simply to spend on entertainment. It was a society in which the average unskilled or semi-skilled worker toiled ten hours a day for about twenty cents an hour. Of every thousand Americans, 939 died without any property to bequeath.

One might well ask: What does a society where women wore corsets and men wore top hats have to say to us? It would be easy to dismiss this era as irrelevant to the problems of our society. But this would be a mistake. In many ways, the late nineteenth century was an age not radically dissimilar from our own.

We are living through an era of unprecedented technological change. So did they. They witnessed the invention of the light bulb, the telephone, and the discovery of germs. Our society is undergoing a communication revolution. Their society did too, with the invention of the telephone and the laying of the transatlantic telegraph cable and the appearance of the mass circulation newspaper and magazine.

Many think that our society is uniquely affected by globalization. But late nineteenth century America was also reshaped by global forces. Much as the contemporary United States has been radically reshaped by massive foreign immigration, so was late nineteenth century America. Late nineteenth century America became increasingly embroiled in foreign affairs lying well outside its borders. Other similarities include bitter partisanship in politics, disputed elections, deep worries about the corrupting influence of money in politics, and angry debates over morality and women’s roles.

Many of the issues that we think of as uniquely modern were hotly debated during the late nineteenth century: corruption in business and government, ostentatious displays of wealth, the ruthless exploitation of natural resources, the growth of corporate power, and the gulf between the rich and the poor.

Even drugs, which we tend to think of as a modern plague, first became a problem during the late nineteenth century. By 1900, one in 200 Americans was addicted to opiates or cocaine. Many wounded Civil War veterans returned home addicted to morphine, a pain-killing opiate. The typical user became addicted during medical treatment. By the end of the nineteenth century, opiates could be legally purchased at corner drugstores. Laudanum, a form of opium, cost twenty-eight cents for a three-ounce bottle from Sears, Roebuck.

In 1885, cocaine was introduced as an elixir for every ailment from depression to hay fever. A label instructed users: “For catarrh and all head disease, snuff very little up the nose five times a day until cured….” Advertisements urged mothers to give cranky children a dose of Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, which was laced with morphine.

By the early twentieth century, the human cost of drug addiction had become obvious, and the country enacted laws criminalizing the manufacture and distribution of addictive drugs.

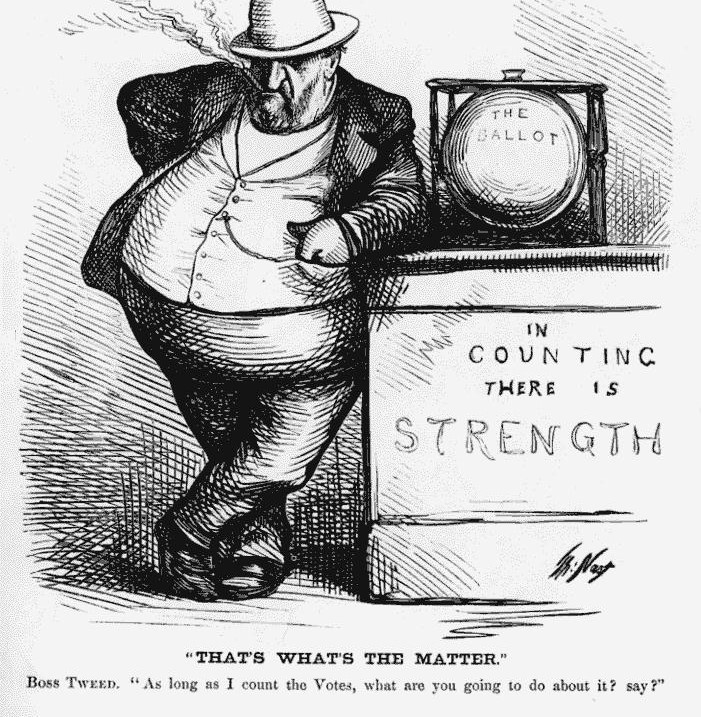

The Gilded Age

Mark Twain called the late nineteenth century the “Gilded Age.” In the popular view, the late 19th century was a period of greed and guile, when rapacious robber barons, unscrupulous speculators, and corporate buccaneers engaged in shady business practices and vulgar displays of wealth. It is easy to caricature the Gilded Age as an era of corruption, scandal-plagued politics, conspicuous consumption, and unfettered capitalism. But it is more useful to think of this period as modern America’s formative era, when the rules of modern politics and business practice were just beginning to be written.

It was during the Gilded Age that Congress passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to break up monopolistic business combinations, and the Interstate Commerce Act, to regulate railroad rates. State governments created commissions to regulate utilities and laws regulating work conditions. Several states filed suits against corporate trusts and tried to revoke the charges of firms that joined trusts.

The Gilded Age was an era of intense political partisanship including disputes over currency, tariffs, political corruption, political patronage, and monopolistic business trusts. This era saw the rapid growth of cities vertically and horizontally and the emergence of new communication technologies and forms of transportation. During this period, mass immigration dramatically altered the population’s ethnic and religious composition.

The Purity Crusade

During the Gilded Age there were repeated attempts to enforce moral purity. In 1880, Massachusetts became the first state to reenact “Blue Laws” that prohibited most forms of business on Sunday. Lotteries, which had been widely used by government in the early nineteenth century to raise revenue, were outlawed, by 1890, in 43 of the 44 states. A number of states enacted laws forbidding horse racing, boxing, and even the manufacture of cigarettes. The earliest attempts to suppress narcotics were made. In 1877, Utah became the first state to forbid the sale of opiates for non-medical purposes.

The largest movement to enforce morality was the movement to prohibit the manufacture and sale of alcohol. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which was founded in 1874, lobbied for a constitutional amendment to prohibit alcohol.

Perhaps the most striking example of the politics of piety was the crusade to enforce sexual prudery. In 1872, Congress enacted the Comstock Act, which banned obscene literature from the mails. The law was interpreted broadly and was used to prevent the distribution of birth control information and contraceptive devices through the mails. The law was named for Anthony Comstock, head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, who became the government agent responsible for enforcing the statute. Comstock had 3,000 persons arrested for obscenity and took credit for hounding sixteen people to their deaths. Among the books he successfully banned were Fanny Hill and A Peep Behind the Curtains of a Female Seminary. He also convinced the Department of Interior to dismiss Walt Whitman for writing poetry that he considered obscene.

Many Northerners, mainly Republican in politics, were convinced that one of the Civil War’s lessons was that government action was sometimes necessary to solve deep-seated social problems. During the Gilded Age, there were repeated attempts to use government to purify and morally uplift society. Laws were enacted against polygamy and obscenity. At the state and local level, there were repeated efforts to censor books, the theater, and, in the first decade of the twentieth century, the movies.

The most contentious moral issue in politics involved prohibition of beer and whiskey. Many Catholic and German Lutheran voters were deeply offended by efforts to use government to enforce moral standards. Together, Catholics and German Lutheran made up about thirty-five percent of the Northern electorate and in urban areas Germans alone comprised fifteen to fifty percent of the urban vote.

There were also attempts to purify the American society by excluding undesirable groups and “uplifting” the electorate. After the Civil War, for the first time there were concerted efforts to restrict foreign immigration. The first group to be excluded were Chinese immigrants in 1882, a subject that is discussed in our unit on immigration.