The Youth Revolt and New Left

The Youth Revolt

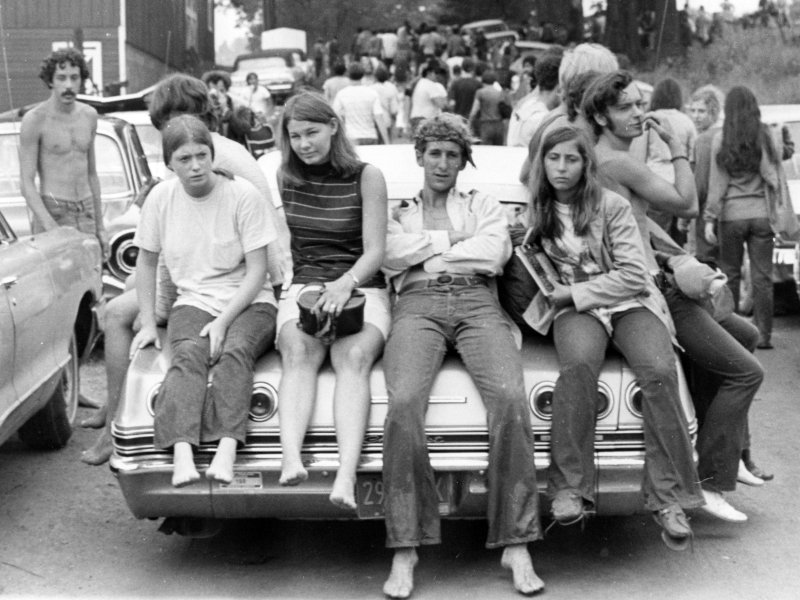

During the 1960s, one age group of Americans loomed larger than any other: the youth. Their skepticism of corporate and bureaucratic authority, their strong emotional identification with the underprivileged, and their intense desire for stimulation and instant gratification shaped the nation’s politics, dress, music, and film.

Unlike their parents, who had grown-up amid the hardships of the Depression and the patriotic sacrifices of World War II, young people of the 1960s grew up during a period of rapid economic growth. Feeling a deep sense of economic security, they sought personal fulfillment and tended to dismiss their parents generation’s success-oriented lives. “Never trust anyone over 30,” went a popular saying.

Never before had young people been so numerous or so well-educated. During the 1960s, there was a sudden explosion in the number of teenagers and young adults. As a result of the depressed birthrates during the 1930s and the post-war baby boom, the number of young people aged 14 to 25 jumped forty percent in a decade constituting twenty percent of the nation’s population. The nation’s growing number of young people received far more schooling than their parents. Over 75 percent graduated high school, and nearly forty percent went on to higher education.

At no earlier time in American history had the gulf between the generations seemed so wide. People spoke of a “generation gap” separating the young from their elders. Blue jeans, long hair, psychedelic drugs, casual sex, hippie communes, campus demonstrations, and rock music all became symbols of the distance separating youth from the world of conventional adulthood.

The New Left

Late in the spring of 1962, five dozen college students gathered at a lakeside camp near Port Huron, Michigan, to discuss politics. For four days and nights, the members of an obscure student group, known as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), talked passionately about such topics as civil rights, foreign policy, and the quality of American life. At 5 a.m. on June 16, the gathering ended when the participants agreed on a political platform that expressed their sentiments. This manifesto, one of the pivotal political documents of the 1960s, became known as the Port Huron Statement.

The goal set forward in the Port Huron Statement was the creation of a radically new democratic political movement in the United States that rejected hierarchy and bureaucracy. In its most important paragraphs, the document called for “participatory democracy”—direct individual involvement in the decisions that affected their lives. This notion would become the battle cry of the student movement of the 1960s—a movement that came to be known as the New Left.

The Port Huron Statement’s chief author was Tom Hayden. Hayden was born in 1939, in Royal Oak, Michigan, a predominantly Catholic working-class suburb of Detroit. From an early age, he was unusually politically conscious and questioning of established authority. In high school, his idols were critics of conventional society, such as J. D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield and Mad Magazine‘s Alfred E. Neuman. He then attended the University of Michigan, read Jack Kerouac’s beat novel On the Road, hitchhiked across the country, and witnessed student protests at the University of California at Berkeley. He spent much of 1961 in the South and was once badly beaten by local whites in McComb, Mississippi.

During the 1960s, Tom Hayden became one of the key figures in the New Left. In 1968, he flew to North Vietnam in protest of the Vietnam War. The next year, he gained further notoriety as one of the Chicago Seven defendants who were acquitted of charges of conspiring to disrupt the 1968 Democratic presidential convention. Briefly, Hayden dropped out of politics, moved to Venice, California, and lived under a pseudonym. Later, he married actress Jane Fonda and became a member of the California legislature. During the 1960s, thousands of young college students, like Tom Hayden, became politically active.

The first issue to spark student radicalism was the impersonality of the modern university, which many students criticized for being too bureaucratic and formal. Students questioned university requirements, restrictions on student political activities, and dormitory rules that limited the hours that male and female students could socialize with each other. Restrictions on students handing out political pamphlets on university property led to the first campus demonstrations that broke out at the University of California at Berkeley, and soon spread to other campuses.

Involvement in the Civil Rights Movement in the South initiated many students into radical politics. In the early 1960s, many white students from Northern universities began to participate in voter registration drives, freedom schools, sit-ins, and freedom rides in order to help desegregate the South. For the first time, many witnessed poverty, discrimination, and violence first hand.

Student radicalism also drew inspiration from a literature of social criticism that flourished in the 1950s. During that decade, many of the most popular films, novels, and writings aimed at young people criticized conventional middle class life. Popular films, like Rebel Without a Cause, and popular novels, like J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, celebrated sensitive, directionless, alienated youths unable to conform to the conventional adult values of suburban and corporate America. Sophisticated works of social criticism, by such maverick sociologists, psychologists, and economists as Herbert Marcuse, Norman O. Brown, Paul Goodman, Michael Harrington, and C. Wright Mills, documented the growing concentration of power in the hands of social elites, the persistence of poverty in a land of plenty, and the stresses and injustices in America’s social order.

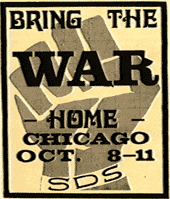

Above all, student radicalism owed its support to student opposition of the Vietnam War. SDS held its first antiwar march in 1965, which attracted at least 15,000 protesters to Washington and commanded wide press attention. Over the next three years, opposition to the war brought thousands of new members to SDS. The organization grew phenomenally, from fewer than a thousand members in 1962 to at least 50,000 in 1968. In addition to its antiwar activities, members of SDS also tried to organize a democratic “interracial movement of the poor” in Northern city neighborhoods.

Many members of SDS quickly grew frustrated by the slow pace of social change and began to embrace violence as a tool to transform society. After 1968, SDS rapidly tore itself apart as an effective political force, and in its final convention in 1969, degenerated into a shouting match between radicals and moderates.

That same year, the Weathermen, a surviving faction of SDS, attempted to launch a guerrilla war in the streets of Chicago—an incident known as the “Days of Rage”—to “tear pig city apart.” Finally, in 1970 three members of the Weathermen blew themselves up in a Greenwich Village brownstone trying to make a bomb out of a stick of dynamite and an alarm clock.

Throughout the 1960s, the SDS and other radical student organizations claimed to speak for the nation’s youth, and in thousands of editorials and magazine articles, journalists accepted this claim. In fact, the SDS represented only a small minority of college students who, themselves, composed a minority of the country’s youth. Far more young Americans voted for George Wallace in 1968 than joined SDS, and most college students during the decade spent far more time studying and enjoying the college experience than protesting.

Nevertheless, radical students did help to draw the nation’s attention to the problem of racism in American society and the moral issues involved in the Vietnam War. In that sense, their impact far exceeded their numbers.

The Making and Unmaking of a Counterculture

The New Left had a series of heroes, ranging from Marx, Lenin, Ho, and Mao to Fidel, Che, and other revolutionaries. It also had its own uniforms, rituals, and music. Faded-blue work shirts and jeans, wire-rimmed glasses, and work shoes were de rigueur even if the dirtiest work the wearer performed was taking notes in a college class. The proponents of the New Left emphasized their sympathy with the working class—an emotion that was seldom reciprocated—and listened to labor songs that once fired the hearts of unionists. The political protest folk music of Greenwich Village—of Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, and their crowd—inspired the New Left.

But the New Left was only one part of youth protest during the 1960s. While the New Left labored to change the world and remake American society, other youths attempted to alter themselves and reorder consciousness. Variously labeled the counterculture, hippies, or flower children, they had their own heroes, music, dress, and approach to life.

In theory, supporters of the counterculture rejected individualism, competition, and capitalism. Adopting rather unsystematic ideas from eastern religions, they sought to become one with the universe. Rejection of monogamy and the traditional nuclear family gave way to the tribal or communal ideal, where members renounced individualism and private property and shared food, work, and sex. In such a community, love was a general abstract ideal rather than a focused emotion.

The quest for oneness with the universe led many youths to experiment with hallucinogenic drugs. LSD had a particularly powerful allure. Under its influence, poets, musicians, politicians, and thousands of other Americans claimed to have tapped into an all-powerful spiritual force. Timothy Leary, the Harvard professor who became the leading prophet of LSD, asserted that the drug would unlock the universe.

Although LSD was outlawed in 1966, the drug continued to spread. Perhaps some takers discovered profound truths, but by the late 1960s, drugs had done more harm than good. The history of the Haight-Ashbury section of San Francisco illustrated the problems caused by drugs. In 1967, Haight was the center of the counterculture, the home of the flower children. In the “city of love,” hippies ingested LSD, smoked pot, listened to “acid rock,” and proclaimed the dawning of a new age. Yet the area was suffering from severe problems. High levels of racial violence, venereal disease, rape, drug overdoses, and poverty ensured more bad trips than good.

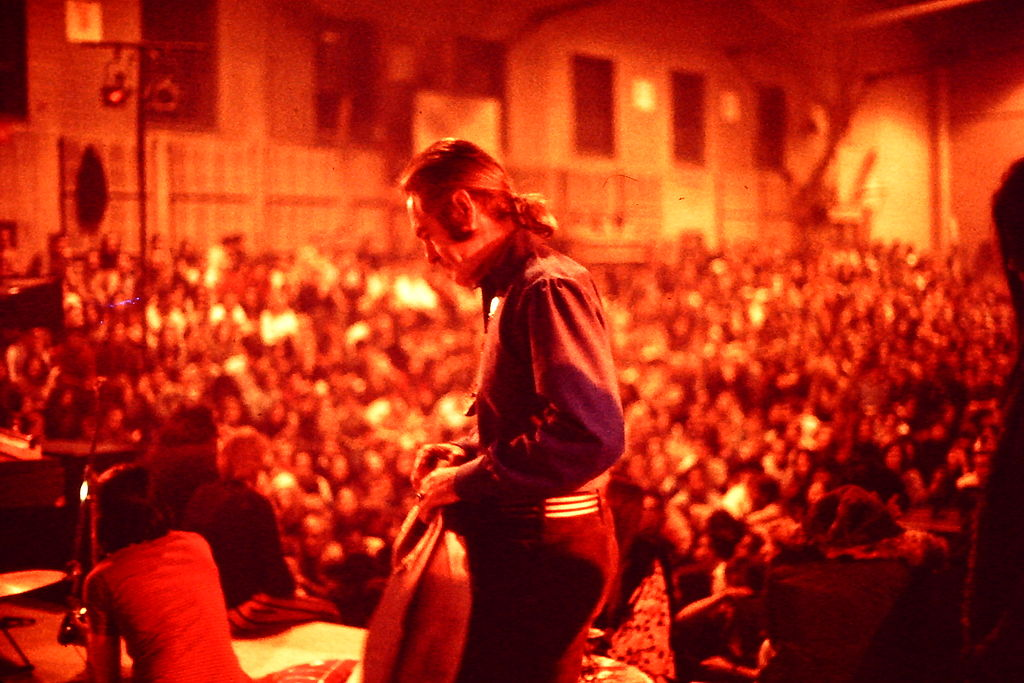

Even music, which along with drugs and sex formed the counterculture trinity, failed to alter human behavior. In 1969, journalists hailed the Woodstock music festival as a symbol of love. But a few months later, a group of Hell’s Angels violently interrupted the Altamont Raceway music festival. As Mick Jagger sang “Under My Thumb,” an Angel stabbed a black man to death.

Like the New Left, the counterculture fell victim to its own excesses. Sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll did not solve the problems facing the United States. And by the end of the 1960s, the counterculture had lost its force.

Nevertheless, the counterculture left a lasting impact on American fashion, music, and attitudes and behavior. The sexual revolution, the use of psychoactive drugs, more casual dress and language, longer hair on men and shorter hair for women — all were lasting legacies of the counterculture.