The Struggle Continues

Black Nationalism and Black Power

At the same time that such civil rights leaders as the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. fought for racial integration, other black leaders emphasized separatism and identification with Africa. Black Nationalist sentiment was not new. During the early nineteenth century, black leaders such as Paul Cuffe and Martin Delaney, convinced that blacks could never achieve true equality in the United States, advocated migration overseas. At the turn of the century, Booker T. Washington and his followers emphasized racial solidarity, economic self-sufficiency, and black self-help. At the end of World War I, millions of black Americans were attracted by Marcus Garvey’s call to drop the fight for equality in America and instead “plant the banner of freedom on the great continent of Africa.”

One of the most important expressions of the separatist impulse during the 1960s was the rise of the Black Muslims, which attracted 100,000 members. Founded in 1931, in the depths of the Depression, the Nation of Islam drew its appeal from among the growing numbers of urban blacks living in poverty. The Black Muslims elevated racial separatism into a religious doctrine and declared that whites were doomed to destruction. “The white devil’s day is over,” Black Muslim leader Elijah Muhammad cried. “He was given six thousand years to rule…He’s already used up most trapping and murdering the black nations by the hundreds of thousands. Now he’s worried, worried about the black man getting his revenge.” Unless whites acceded to the Muslim demand for a separate territory for themselves, Muhammad said, “Your entire race will be destroyed and removed from this earth by Almighty God. And those black men who are still trying to integrate will inevitably be destroyed along with the whites.”

The Black Muslims did more than vent anger and frustration. The organization was also a vehicle of black uplift and self-help. The Black Muslims called upon black Americans to “wake up, clean up, and stand up” in order to achieve true freedom and independence. To root out any behavior that conformed to racist stereotypes, the Muslims forbade eating pork and cornbread, drinking alcohol, and smoking cigarettes. Muslims also emphasized the creation of black businesses.

The most controversial exponent of Black Nationalism was Malcolm X. The son of a Baptist minister who had been an organizer for Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association, he was born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, and grew up in Lansing, Michigan. A reformed drug addict and criminal, Malcolm X learned about the Black Muslims in a high security prison. After his release from prison in 1952, he adopted the name Malcolm X to replace “the white slave-master name which had been imposed upon my paternal forebears by some blue-eyed devil.” He quickly became one of the Black Muslims’ most eloquent speakers, denouncing alcohol, tobacco, and extramarital sex.

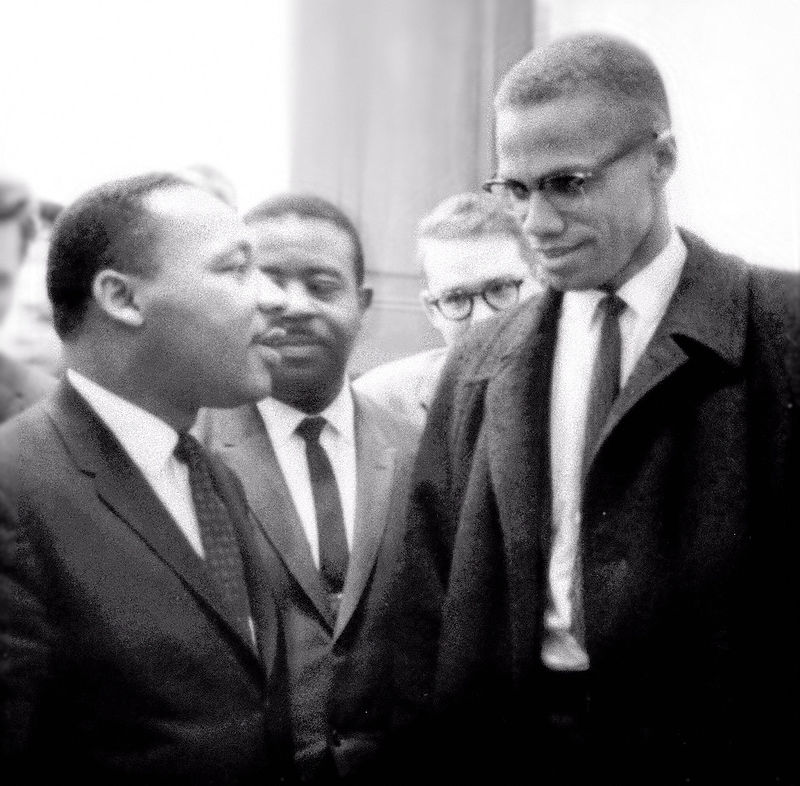

Condemned by some whites as a demagogue for such statements as “If ballots won’t work, bullets will,” Malcolm X gained widespread public notoriety by attacking the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as a “chump” and an Uncle Tom, by advocating self-defense against white violence, and by emphasizing black political power.

Malcolm X’s main message was that discrimination led many black Americans to despise themselves. “The worst crime the white man has committed,” he said, “has been to teach us to hate ourselves.” Self-hatred caused black Americans to lose their identity, straighten their hair, and become involved in crime, drug addiction, and alcoholism.

In March 1964 (after he violated an order from Elijah Muhammad and publicly rejoiced at the assassination of President John F. Kennedy), Malcolm X withdrew from Elijah Muhammad’s organization and set up his own Organization of Afro-Americans. Less than a year later, his life ended in bloodshed. On February 21, 1965, in front of 400 followers, he was shot and killed, apparently by followers of Black Muslim leader Elijah Muhammad, as he prepared to give a speech in New York City.

Inspired by Malcolm X’s example, young black activists increasingly challenged the traditional leadership of the Civil Rights Movement and its philosophy of nonviolence. The single greatest contributor to the growth of militancy was the violence perpetrated by white racists. One of the most publicized incidents took place in June 1964, when three civil rights workers—two whites, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, and one black, James Chaney—disappeared near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Six weeks after they were reported missing, the bodies of the men were found buried under a dam. All three had been beaten, then shot. In December, the sheriff and deputy sheriff of Neshoba County, Mississippi, along with 19 others, were arrested on charges of violating the three men’s civil rights; but just six days later the charges were dropped. David Dennis, a black civil rights worker, spoke at James Chaney’s funeral. He angrily declared, “I’m sick and tired of going to the funerals of black men who have been murdered by white men…I’ve got vengeance in my heart.”

In 1966, two key civil rights organizations—SNCC and CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality)—embraced Black Nationalism. In May, Stokely Carmichael was elected chairman of SNCC and proceeded to transform SNCC from an interracial organization committed to nonviolence and integration into an all-black organization committed to “black power.” “Integration is irrelevant,” declared Carmichael. “Political and economic power is what the black people have to have.” Although Carmichael initially denied that “black power” implied racial separatism, he eventually called on blacks to form their own separate political organizations. In July 1966—one month after James Meredith, the black Air Force veteran who had integrated the University of Mississippi, was ambushed and shot while marching for voting rights in Mississippi—CORE also endorsed black power and repudiated nonviolence.

Of all the groups advocating racial separatism and black power, the one that received the widest publicity was the Black Panther Party. Formed in October 1966, in Oakland, California, the Black Panther party was an armed revolutionary socialist organization advocating self-determination for black ghettoes. “Black men,” declared one party member, “must unite to overthrow their white ‘oppressors,’ becoming ‘like panthers—smiling, cunning, scientific, striking by night and sparing no one!’” The Black Panthers gained public notoriety by entering the gallery of the California State Assembly brandishing guns and by following police to prevent police harassment and brutality toward blacks.

Separatism and black nationalism attracted no more than a small minority of black Americans. Public opinion polls indicated that only about 15 percent of black Americans identified themselves as separatists and that the overwhelming majority of blacks considered Martin Luther King, Jr. their favored spokesperson. The older civil rights organizations, such as the NAACP, rejected separatism and black power, viewing it as an abandonment of the goals of nonviolence and integration.

Yet despite their relatively small following, black power advocates exerted a powerful and positive influence upon the Civil Rights Movement. In addition to giving birth to a host of community self-help organizations, supporters of black power spurred the creation of black studies programs in universities and encouraged black Americans to take pride in their racial background and to recognize that “black is beautiful.” A growing number of black Americans began to wear “Afro” hairstyles and take African or Islamic surnames. Singer James Brown captured the new spirit: “Say it loud—I’m black and I’m proud.”

In an effort to maintain support among more militant blacks, civil rights leaders began to address the problems of the black lower classes who lived in the nation’s cities. By the mid-1960s, King had begun to move toward the political left. He said it did no good to be allowed to eat in a restaurant if you had no money to pay for a hamburger. King denounced the Vietnam War as “an enemy of the poor,” described the United States as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today,” and predicted that “the bombs that [Americans] are dropping in Vietnam will explode at home in inflation and unemployment.” He urged a radical redistribution of wealth and political power in the United States in order to provide medical care, jobs, and education for all of the country’s people. And he spoke of the need for a second “March on Washington” by “waves of the nation’s poor and disinherited,” who would “stay until America responds…[with] positive action.” The time had come for radical measures “to provide jobs and income for the poor.”

The Civil Rights Movement Moves North

On August 11, 1965, riots ignited in Watts, a predominantly black section of Los Angeles, after the arrest of a 21-year-old for drunk driving. The riots occurred only five days after President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. The violence lasted five days and resulted in 34 deaths, 3,900 arrests, and the destruction of over 744 buildings and 200 businesses in a 20-square-mile area. Rioters smashed windows, hurled bricks and bottles from rooftops, and stripped store shelves.

Over the next four summers, the nation’s inner cities experienced a wave of violence and rioting. The worst violence occurred during the summer of 1967, when riots occurred in 127 cities. In Newark, 26 persons lost their lives, over 1,500 were injured, and 1,397 were arrested. In Detroit, 43 people died, $500 million in property was destroyed, and 14-square-miles were gutted by fire. The last major wave of violence occurred following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. Violence erupted in 168 cities, leaving 46 dead, 3,500 injured, and $40 million worth of damage. In Washington, D.C., fires burned within three blocks of the White House.

In 1968, President Johnson appointed a commission to examine the causes of the race riots of the preceding three summers. Led by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, the commission attributed racial violence to “white racism” and its heritage of discrimination and exclusion. Joblessness, poverty, a lack of political power, decaying and dilapidated housing, police brutality, and poor schools bred a sense of frustration and rage that had exploded into violence. The commission warned that unless major steps were taken, the United States would inevitably become “two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

Until 1964, most white Northerners regarded race as a peculiarly Southern problem that could be solved by extending political and civil rights to Southern blacks. Beginning in 1964, however, the nation learned that discrimination and racial prejudice were nationwide problems and that black Americans were demanding not just desegregation in the South, but equality in all parts of the country. The nation also learned that resistance to black demands for equal rights was not confined to the Deep South, but existed in the North as well.

In the North, African Americans suffered, not from de jure (legal) segregation, but from de facto discrimination in housing, schooling, and employment—discrimination that lacked the overt sanction of law. “De facto segregation,” wrote James Baldwin, “means that Negroes are segregated but nobody did it.” The most obvious example of de facto segregation was the fact that the overwhelming majority of Northern black schoolchildren attended predominantly black inner-city schools, while most white children attended schools with an overwhelming majority of whites. In 1968—fourteen years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision—federal courts began to order busing as a way to deal with de facto segregation brought about by housing patterns. In April 1971, in the case of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, the Supreme Court upheld “bus transportation as a tool of school desegregation.”

The Great Society and the Drive for Black Equality

Lyndon B. Johnson had a vision for America. Believing that problems of housing, income, employment, and health were ultimately a federal responsibility, Johnson used the weight of the presidency and his formidable political skills to enact the most impressive array of reform legislation since the days of Franklin Roosevelt. He envisioned a society without poverty or discrimination, in which all Americans enjoyed equal educational and job opportunities. He called his vision the “Great Society.”

A major feature of Johnson’s Great Society was the “War on Poverty.” The federal government raised the minimum wage and enacted programs to train poorer Americans for new and better jobs, including the 1964 Manpower Development and Training Act and the Economic Opportunity Act, which established such programs as the Job Corps and the Neighborhood Youth Corps. To assure adequate housing, in 1966 Congress adopted the Model Cities Act to attack urban blight, set up a cabinet-level Department of Housing and Urban Development, and began a program of rent supplements.

To promote education, Congress passed the Higher Education Act in 1965 to provide student loans and scholarships, the Elementary and Secondary Schools Act of 1965 to pay for textbooks, and the Educational Opportunity Act of 1968 to help the poor finance college educations. To address the nation’s health needs, the Child Health Improvement and Protection Act of 1968 provided for prenatal and postnatal care, the Medicaid Act of 1968 paid for the medical expenses of the poor, and Medicare, established in 1965, extended medical insurance to older Americans under the Social Security system.

Johnson also prodded Congress to pass a broad spectrum of civil rights laws, ranging from the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to the 1968 Fair Housing Act barring discrimination in the sale or rental of housing. In 1965, LBJ issued an executive order requiring government contractors to ensure that job applicants and employees were not discriminated against. It required all contractors to prepare an “affirmative action plan” to achieve these goals.

Johnson broke many other color barriers. In 1966, he named the first black cabinet member and appointed the first black woman to the federal bench. In 1967, he appointed Thurgood Marshall to become the first black American to serve on the Supreme Court. The first Southerner to reside in the White House in half a century, Johnson showed a stronger commitment to improving the position of black Americans than any previous president.

When President Johnson announced his Great Society program in 1964, he promised substantial reductions in the number of Americans living in poverty. When he left office, he could legitimately argue that he had delivered on his promise.

In 1960, 40 million Americans (20 percent of the population) were classified as poor. By 1969, their number had fallen to 24 million (12 percent of the population). Johnson also pledged to qualify the poor for new and better jobs, to extend health insurance to the poor and elderly to cover hospital and doctor costs, and to provide better housing for low-income families. Here, too, Johnson could say he had delivered. Infant mortality among the poor, which had barely declined between 1950 and 1965, fell by one-third in the decade after 1965 as a result of expanded federal medical and nutritional programs. Before 1965, 20 percent of the poor had never seen a doctor. By 1970, the figure had been cut to 8 percent. The proportion of families living in houses lacking indoor plumbing also declined steeply, from 20 percent in 1960 to 11 percent a decade later.

Although critics argued that Johnson took a shotgun approach to reform and pushed poorly thought-out bills through Congress, supporters responded that at least Johnson tried to move toward a more compassionate society. During the 1960s, median black family income rose 53 percent. Black employment in professional, technical, and clerical occupations doubled. Average black educational attainment increased by four years. The proportion of blacks below the poverty line fell from 55 percent in 1960 to 27 percent in 1968. The black unemployment rate fell 34 percent. The country had taken major strides toward extending equality of opportunity to black Americans. In addition, the number of whites below the poverty line dropped dramatically, and such poverty-plagued regions as Appalachia made significant economic strides.

Podcast

“Did the United States Lose the War on Poverty?”

Listen to the podcast entitled, “Did the United States Lose the War on Poverty?”.

White Backlash

Ghetto rioting, the rise of black militancy, and resentment over Great Society social legislation combined to produce a backlash among many whites. Commitment to bringing black Americans into full equality declined. In the wake of the riots, many whites fled the nation’s cities. The Census Bureau estimated that 900,000 whites moved each year from central cities to the suburbs between 1965 and 1970.

The 1968 Republican candidate, Richard Nixon, promised to eliminate “wasteful” federal antipoverty programs and to name “strict constructionists” to the Supreme Court. As president, Nixon moved quickly to keep his commitments. In an effort to curb Great Society social programs, Nixon did away with the Model Cities Program and the Office of Economic Opportunity. “The time may have come,” declared a Nixon aide, “when the issue of race could benefit from a period of benign neglect.” The administration urged Congress not to extend the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and to end the Fair Housing Enforcement Program.

Nixon also made a series of Supreme Court appointments that brought to an end the liberal activist era of the Warren Court. During the 1960s, the Supreme Court greatly increased the ability of criminal defendants to defend themselves. In Mapp v. Ohio (1961), the high court ruled that evidence secured by the police through unreasonable searches must be excluded from trial. In Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), it declared that indigent defendants have a right to a court-appointed attorney. In Escobedo v. Illinois (1964), it ruled that suspects being interrogated by police have a right to legal counsel.

As president, Nixon promised to alter the balance between the rights of criminal defendants and society’s rights. He selected Warren Burger, a moderate conservative, to replace Earl Warren as chief justice of the Supreme Court. He also nominated two conservative white Southerners for a second court vacancy, only to have both nominees rejected (one for financial improprieties, the other for alleged insensitivities to civil rights). Nixon eventually named four justices to the high court: Burger, Harry Blackmun, Lewis Powell, and William Rehnquist.

Under Chief Justice Burger and his successor William Rehnquist, the Supreme Court clarified the remedies that could be used to correct past racial discrimination. In 1974, the Court limited the use of school busing for purposes of racial desegregation by declaring that busing could not take place across school district lines. In 1978, in the landmark Bakke case, the Court held that educational institutions could take race into account when screening applicants, but could not use rigid racial quotas. The following year, however, the court ruled that employers and unions could legally establish voluntary programs, including the use of quotas, to aid minorities and women in employment.

The Struggle Continues

Over the half century, black Americans have made impressive social and economic gains, yet full equality remains an unrealized dream. State-sanctioned segregation in restaurants, hotels, courtrooms, libraries, drinking fountains, and public washrooms was eliminated, and many barriers to equal opportunity were shattered. In political representation, educational attainment, and representation in white collar and professional occupations, African Americans have made striking gains. Between 1960 and 1993, the number of black officeholders swelled from just 300 to nearly 7,984, and the proportion of blacks in professional positions quadrupled. Black mayors have governed many of the nation’s largest cities, including Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.

Respect for black culture has also grown. The number of black performers on television and in film has grown, though most still appear in comedies or crime stories. Today, the most popular television performer (Oprah), many popular movie stars, and many of the most popular musicians and sports stars are black.

Nevertheless, millions of black Americans still do not share fully in the promise of American life. The proportion of lawyers who are black doubled between 1960 and 2017, but it has only gone from 1.3 percent to 5 percent. The percentage of physicians who are African American has increased, from 4.4 percent to 5 percent.

According to census figures, blacks still suffer twice the unemployment rate of whites and earn only about half as much. The poverty rate among black families is three times that of whites—the same ratio as in the 1950s. Black households earn only about $63 for every $100 a white household earns. Forty percent of black children are raised in fatherless homes, and almost half of all black children are born into families earning less than the poverty level.

Separation of the races in housing and schooling remains widespread. Nationally, less than a quarter of all black Americans live in integrated neighborhoods, and only about 38 percent of black children attend racially integrated schools. And despite great gains in black political clout, blacks still do not hold political offices in proportion to their share of the population. In 1965, there were no blacks in the U.S. Senate and only six in the House of Representatives. Nor were there any black governors. By 2015, there were 44 House members but only two black senators and one black governor.

Although the United States has eliminated many obstacles to black progress, reformers maintain that much remains to be done before the country attains Martin Luther King’s dream of a nation where “all of God’s children, black man and white man, Jew and Gentile, Protestant and Catholic, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, `Free at Last, Free at Last, Thank God Almighty, I’m Free at Last.’”