Civil Rights Movement

The March on Washington

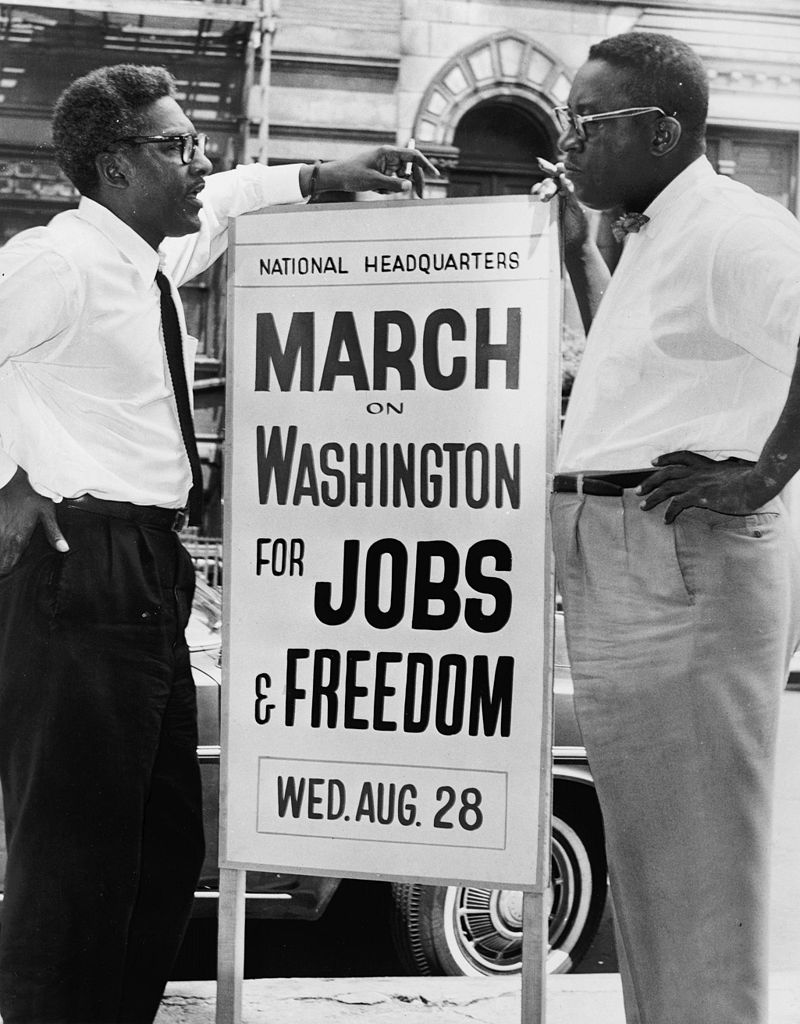

The violence that erupted in Birmingham and elsewhere alarmed many veteran civil rights leaders. In December 1962, two veteran fighters for civil rights, A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, met at the office of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Harlem. Both men were pacifists, eager to rededicate the Civil Rights Movement to the principle of nonviolence. Both men decided that a massive march for civil rights and jobs might provide the necessary pressure to prompt President Kennedy and Congress to act.

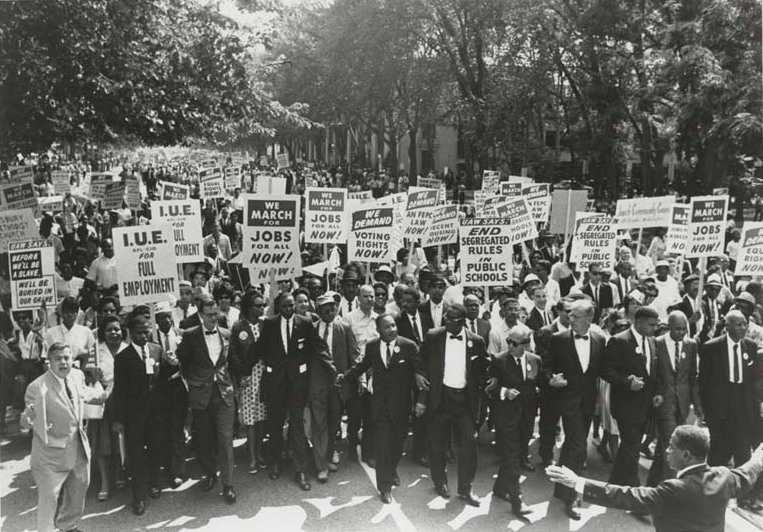

On August 28, 1963, over 200,000 people gathered around the Washington Monument and marched eight-tenths of a mile to the Lincoln Memorial. The marchers carried placards reading: “Effective Civil Rights Laws—Now! Integrated Schools—Now! Decent Housing—Now!” and sang the civil rights anthem, “We Shall Overcome.” Ten speakers addressed the crowd, but the event’s highlight was an address by the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. After he finished his prepared text, he launched into his legendary closing words. “I have a dream,” he declared, “that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood…I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with people’s injustices, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.” As his audience roared their approval, King continued: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.”

History Through…

…Photographs

Review the image below.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

For seven months, debate raged in the halls of Congress. In a futile effort to delay the Civil Rights Bill’s passage, opponents proposed over 500 amendments and staged a protracted filibuster in the Senate.

On July 2, 1964—a little over a year after President Kennedy had sent it to Congress—the Civil Rights Act was enacted into law. It had been skillfully pushed through Congress by President Lyndon Johnson, who took office after Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963. The act prohibited discrimination in voting, employment, and public facilities such as hotels and restaurants, and it established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to prevent discrimination in employment on the basis of race, religion, or sex. Ironically, the provision barring sex discrimination had been added by opponents of the Civil Rights Act in an attempt to kill the bill.

Although most white Southerners accepted the new federal law without resistance, many violent incidents occurred as angry whites vented their rage in shootings and beatings.

The Civil Rights Act was a success despite such incidents. In the first weeks under the 1964 Civil Rights Law, segregated restaurants and hotels across the South opened their doors to black patrons.

Over the next ten years, the Justice Department brought legal suits against more than 500 school districts and more than 400 suits against hotels, restaurants, taverns, gas stations, and truck stops charged with racial discrimination.

Voting Rights

The 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination in employment and public accommodations. But many African Americans were denied an equally fundamental constitutional right, the right to vote. The most effective barriers to black voting were state laws requiring prospective voters to read and interpret sections of the state constitution. In Alabama, voters had to provide written answers to a twenty-page test on the Constitution and state and local government. Questions included: Where do presidential electors cast ballots for president? Name the rights a person has after he has been indicted by a grand jury?

In an effort to bring the issue of voting rights to national attention, Martin Luther King, Jr. launched a voter registration drive in Selma, Alabama, in early 1965. Even though blacks slightly outnumbered whites in the city of 29,500 people, Selma’s voting rolls were 99 percent white and 1 percent black. For seven weeks, King led hundreds of Selma’s black residents to the county courthouse to register to vote.

Nearly 2,000 black demonstrators, including King, were jailed by County Sheriff James Clark for contempt of court, juvenile delinquency, and parading without a permit. After a federal court ordered Clark not to interfere with orderly registration, the sheriff forced black applicants to stand in line for up to five hours before being permitted to take a “literacy” test. Not a single black voter was added to the registration rolls.

When a young black man was murdered in nearby Marion, King responded by calling for a march from Selma to the state capitol of Montgomery, fifty miles away. On March 7, 1965, black voting-rights demonstrators prepared to march. “I can’t promise you that it won’t get you beaten,” King told them, “…but we must stand up for what is right!” As they crossed a bridge spanning the Alabama River, 200 state police with tear gas, night sticks, and whips attacked them. The march resumed on March 21 with federal protection. The marchers chanted: “Segregation’s got to fall…you never can jail us all.”

On March 25 a crowd of 25,000 gathered at the state capitol to celebrate the march’s completion. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressed the crowd and called for an end to segregated schools, poverty, and voting discrimination. “I know you are asking today, ‘How long will it take?’…How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever.”

Within hours of the march’s end, four Ku Klux Klan members shot and killed a 39-year-old white civil rights volunteer from Detroit named Viola Liuzzo. President Johnson expressed the nation’s shock and anger. “Mrs. Liuzzo went to Alabama to serve the struggle for justice,” the President said. “She was murdered by the enemies of justice who for decades have used the rope and the gun and the tar and the feather to terrorize their neighbors.”

Two measures adopted in 1965 helped safeguard the voting rights of black Americans. On January 23, the states completed ratification of the Twenty-Fourth Amendment to the Constitution barring a poll tax in federal elections. At the time, five Southern states still had a poll tax. On August 6, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, which prohibited literacy tests and sent federal examiners to seven Southern states to register black voters. Within a year, 450,000 Southern blacks registered to vote.