The State of Black America in 1960

The State of Black America in 1960

The statistics were grim for black Americans in 1960. Their average life-span was seven years less than white Americans’. Their children had only half the chance of completing high school, only a third the chance of completing college, and a third the chance of entering a profession when they grew up. On average, black Americans earned half as much as white Americans and were twice as likely to be unemployed.

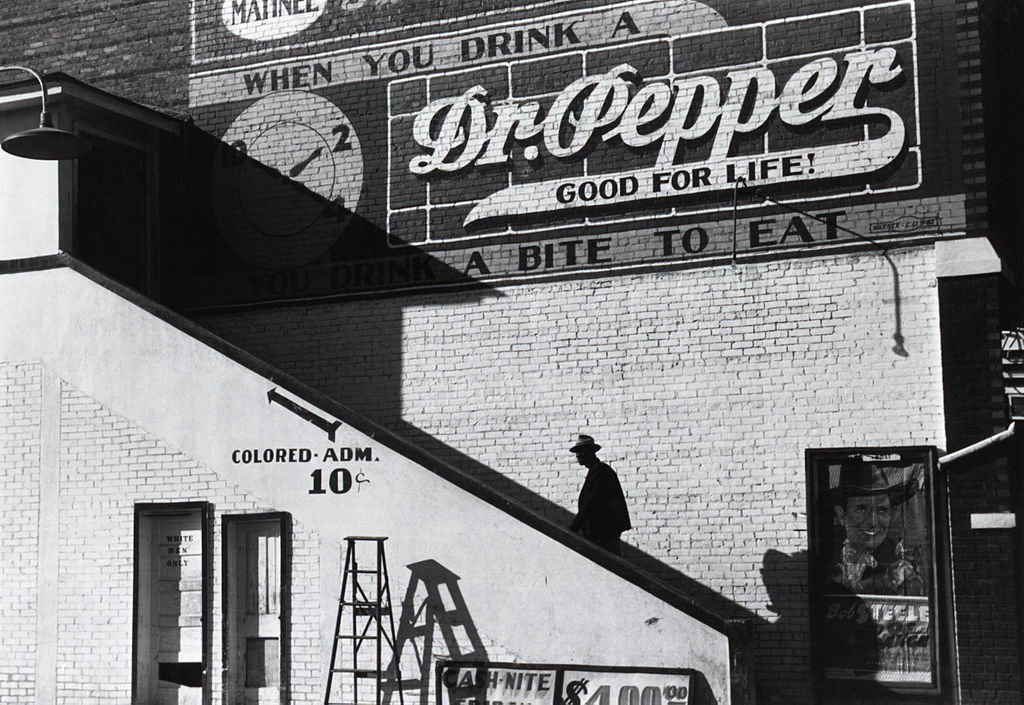

Despite a string of court victories during the late 1950s, many black Americans were still second-class citizens. Six years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, only 49 Southern school districts had desegregated, and less than 1.2 percent of black schoolchildren in the eleven states of the old Confederacy attended public school with white classmates. Less than a quarter of the South’s black population of voting age could vote. In certain Southern counties blacks could not vote, serve on grand juries and trial juries, or frequent all-white beaches, restaurants, and hotels.

In the North, too, black Americans suffered humiliation, insult, embarrassment, and discrimination. Many neighborhoods, businesses, and unions almost totally excluded blacks.

Just as black unemployment had increased in the South with the mechanization of cotton production, black unemployment in Northern cities soared as labor-saving technology eliminated many semiskilled and unskilled jobs that historically had provided many blacks with work.

Black families experienced severe strain. The proportion of black families headed by women jumped from 8 percent in 1950 to 21 percent in 1960. “If you’re white, you’re right” a black folk saying declared; “if you’re brown stick around; if you’re black, stay back.”

During the 1960s, however, a growing hunger for full equality arose among black Americans. The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave voice to the new mood: “We’re through with tokenism and gradualism and see-how-far-you’ve-comeism. We’re through with we’ve-done-more-for-your-people-than-anyone-elseism. We can’t wait any longer. Now is the time.”

Freedom Now

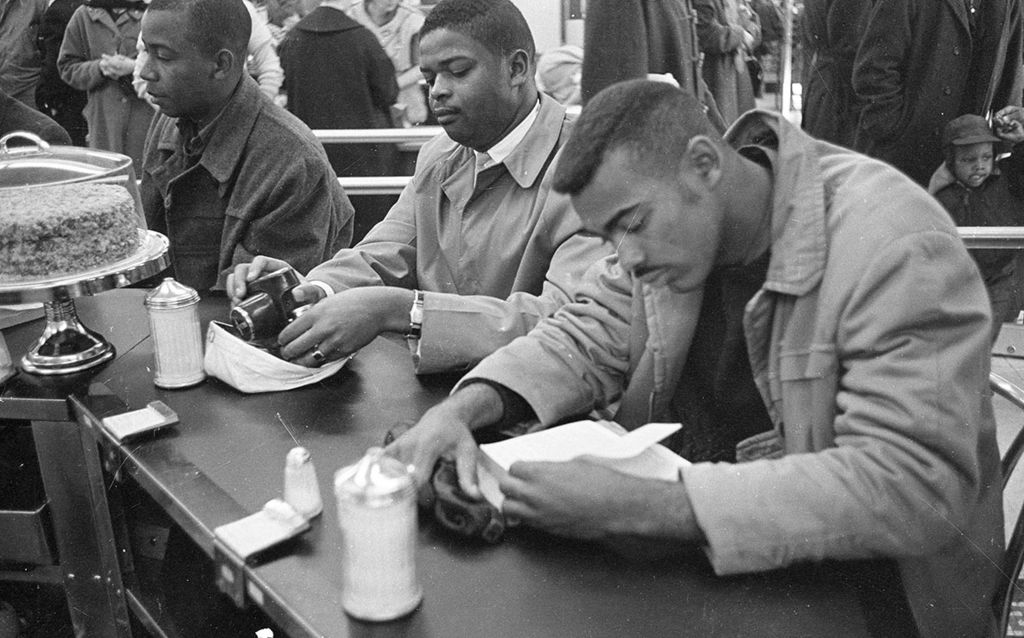

“Now is the time.” These words became the credo and rallying cry for a generation. On Monday, February 1, 1960, four black freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College—Ezell Blair, Jr., Franklin McClain, Joseph McNeill, and David Richmond—walked into the F.W. Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina, and sat down at the lunch counter. They asked for a cup of coffee. A waitress told them that she would only serve them if they stood.

Instead of walking away, the four college freshmen stayed in their seats until the lunch counter closed—giving birth to the “sit-in.” The next morning, the four college students re-appeared at Woolworth’s, accompanied by 25 fellow students. By the end of the week, protesters filled Woolworth’s and other lunch counters in town. Now was their time, and they refused to end their nonviolent protest against inequality. Six months later, white city officials granted blacks the right to be served in a restaurant.

Although the four student protesters ascribed to Dr. King’s doctrine of nonviolence, their opponents did not—assaulting the black students both verbally and physically. When the police finally arrived, they arrested black protesters, not the whites who tormented them.

By the end of February, lunch counter sit-ins had spread through thirty cities in seven Southern states. In Charlotte, North Carolina, a storekeeper unscrewed the seats from his lunch counter. Other stores roped-off seats so that every customer had to stand. Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Virginia, hastily passed anti-trespassing laws to stem the outbreak of sit-ins. Despite these efforts, the nonviolent student protests spread across the South. Students attacked segregated libraries, lunch counters, and other “public” facilities.

In April, some 142 student sit-in leaders from eleven states met in Raleigh, North Carolina, and voted to set up a new group to coordinate the sit-ins, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. told the students that their willingness to go to jail would “be the thing to awaken the dozing conscience of many of our white brothers.”

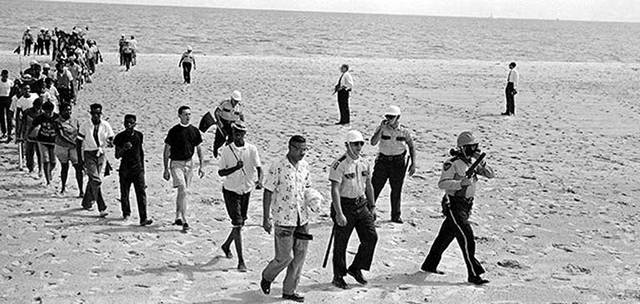

In the summer of 1960, sit-ins gave way to “wade-ins” at segregated public beaches. In Atlanta, Charlotte, Greensboro, and Nashville, black students lined up at white-only box offices of segregated movie theaters. Other students staged pray-ins (at all-white churches), study-ins (at segregated libraries), and apply-ins (at all-white businesses).

By the end of 1960, 70,000 people had taken part in sit-ins in over 100 cities in twenty states. Police arrested and jailed more than 3,600 protesters, and authorities expelled 187 students from college because of their activities. Nevertheless, the new tactic worked. On March 21, 1960, lunch counters in San Antonio, Texas, were integrated. By August 1, lunch counters in 15 states had been integrated. By the end of the year, protesters had succeeded in integrating eating establishments in 108 cities.

The Greensboro sit-in initiated a new, activist phase in black America’s struggle for equal rights. Fed up with the slow, legalistic approach that characterized the Civil Rights Movement in the past, Southern black college students began to attack Jim Crow directly. In the upper South, federal court orders and student sit-ins successfully desegregated lunch counters, theaters, hotels, public parks, churches, libraries, and beaches. But in three states—Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina—segregation in restaurants, hotels, and bus, train, and airplane terminals remained intact. Young civil rights activists launched new assaults against segregation in those states.

To the Heart of Dixie

In early May 1961, a group of thirteen men and women, both black and white, set out from Washington, D.C., on two buses. They called themselves “freedom riders.” They wanted to demonstrate that segregation prevailed throughout much of the South despite a federal ban on segregated travel on interstate buses. The freedom riders’ trip was sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), a civil rights group dedicated to breaking down racial barriers through nonviolent protest. Inspired by the nonviolent, direct action ideals incorporated in the philosophy of Indian Nationalist Mahatma Gandhi, the freedom riders were willing to endure jail and suffer beatings to achieve integration. “We can take anything the white man can dish out,” said one black freedom rider, “but we want our rights…and we want them now.”

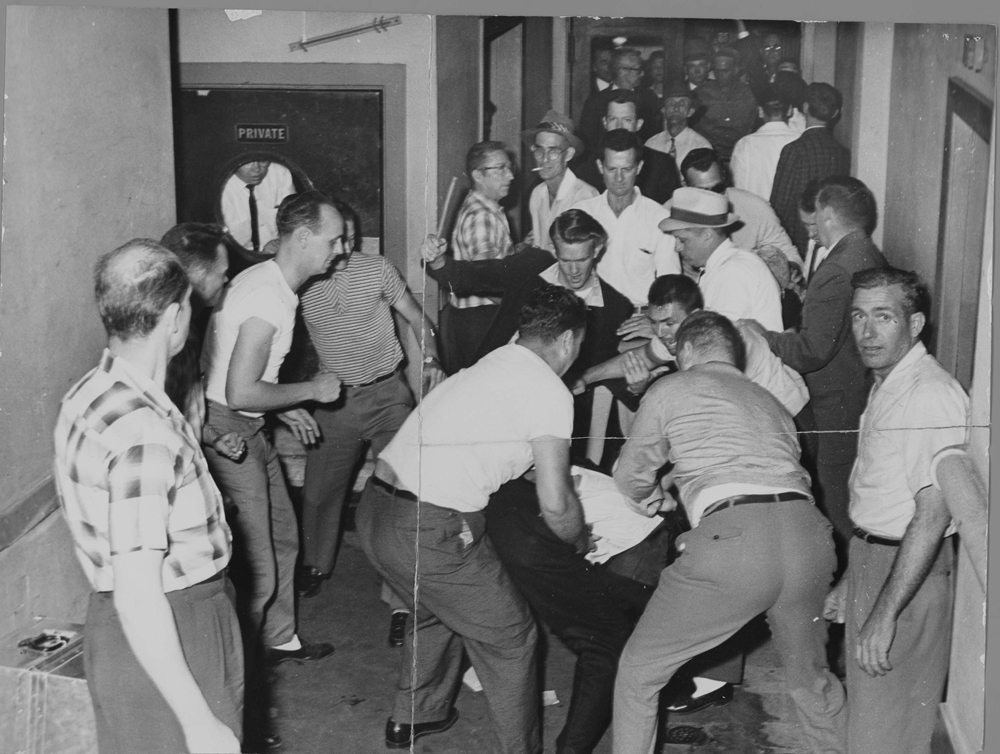

In Virginia and North Carolina, the freedom riders met with little trouble. Black freedom riders were able to use white restrooms and sit at white lunch counters. But in Winnsboro, South Carolina, police arrested two black freedom riders, and outside of Anniston, Alabama, a white hurled a bomb through one of the bus’s windows, setting the vehicle on fire. Waiting white thugs beat the freedom riders as they tried to escape the smoke and flames. Eight other whites boarded the second bus and assaulted the freedom riders before police restrained the attackers.

In Birmingham, Alabama, another mob attacked the second bus with blackjacks and lengths of pipe. In Montgomery, a club-swinging mob of 100 whites attacked the freedom riders; and a group of white youths poured an inflammable liquid on one black man, igniting his clothing. Local police arrived ten minutes later, state police an hour later. Explained Montgomery’s police commissioner: “We have no intention of standing police guard for a bunch of troublemakers coming into our city.”

President Kennedy was appalled by the violence. He hastily deputized 400 federal marshals and Treasury agents and flew them to Alabama to protect the freedom riders’ rights. The president publicly called for a “cooling-off period,” but conflict continued. When the freedom riders arrived in Jackson, Mississippi, 27 were arrested for entering a “white-only” washroom and were sentenced to sixty days on the state prison farm.

The threat of racial violence in the South led the Kennedy administration to pressure the Interstate Commerce Commission to desegregate air, bus, and train terminals. In more than 300 Southern terminals, signs saying “white” and “colored” were taken down from waiting room entrances and lavatory doors.

Civil rights activists next aimed to open state universities to black students. Many Southern states opened their universities to black students without incident. Other states were stiff-backed in their opposition to integration. The depth of hostility to integration was apparent in an incident that took place in February 1956. A young woman named Autherine Lucy became the first black student ever admitted to the University of Alabama. A mob of 1,000 greeted the young woman with the chant, “Keep ‘Bama White!” Two days later, rioting students threw stones and eggs at the car she was riding in to attend class. Lucy decided to withdraw from school, and for the next seven years, no black students attended the University of Alabama.

A major breakthrough occurred in September 1962, when a federal court ordered the state of Mississippi to admit James Meredith—a nine-year veteran of the Air Force—to the University of Mississippi in Oxford. Ross Barnett, the state’s governor, promised on statewide television that he would “not surrender to the evil and illegal forces of tyranny” and would go to jail rather than permit Meredith to register for classes. Barnett flew into Oxford, named himself special registrar of the university, and ordered the arrest of federal officials who tried to enforce the court order.

James Meredith refused to back down. A “man with a mission and a nervous stomach,” Meredith was determined to get a higher education. “I want to go to the university,” he said. “This is the life I want. Just to live and breathe—that isn’t life to me. There’s got to be something more.” He arrived at the Ole Miss campus in the company of police officers, federal marshals, and lawyers. Angry white students waited, chanting, “Two, four, six, eight—we don’t want to integrate.”

Four times James Meredith tried unsuccessfully to register at Ole Miss. He finally succeeded on the fifth try, escorted by several hundred federal marshals. The ensuing riot left 2 people dead and 375 injured, including 166 marshals. Ultimately, President Kennedy sent 16,000 troops to stop the violence.

Bombingham

By the end of 1961, protests against segregation, job discrimination, and police brutality had erupted from Georgia to Mississippi and from Tennessee to Alabama. Staunch segregationists responded by vowing to defend segregation. The symbol of unyielding resistance to integration was George C. Wallace, a former state judge and a one-time state Golden Gloves featherweight boxing champion. Elected on an extreme segregationist platform, Wallace promised to “stand in the schoolhouse door” and go to jail before permitting integration. At his inauguration in January 1963, Wallace declared: “I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

It was in Birmingham, Alabama, that civil rights activists faced the most determined resistance. A sprawling steel town of 340,000, Birmingham had a long history of racial acrimony. In open defiance of Supreme Court rulings, Birmingham had closed its 38 public playgrounds, eight swimming pools, and four golf courses rather than integrate them. Calling Birmingham “the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States,” the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. announced in early 1963 that he would lead demonstrations in the city until demands for fair hiring practices and desegregation were met.

Day after day, well-dressed and carefully groomed men, women, and children marched against segregation—only to be jailed for demonstrating without a permit. On April 12, King was arrested. While in jail, he wrote his now-famous “Letter from Birmingham City Jail,” a scathing attack on a group of white clergymen who asked black Americans to wait patiently for equal rights. On pieces of toilet paper and newspaper margins, King wrote, “I am convinced that if your white brothers dismiss us as `rabble rousers’ and ‘outside agitators’—those of us who are working through the channels of nonviolent direct action—and refuse to support our nonviolent efforts, millions of Negroes, out of frustration and despair, will seek solace and security in black nationalist ideologies, a development that will lead inevitably to a frightening racial nightmare.”

For two weeks, all was quiet, but in early May, demonstrations resumed with renewed vigor. On May 2 and again on May 3, more than a thousand of Birmingham’s black youth marched for equal rights. In response, Birmingham’s police chief, Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, unleashed police dogs on the children and sprayed them with fire hoses with 700 pounds of pressure. Watching the willful brutality on television, millions of Americans, white and black, were shocked by the face of segregation.

Tension mounted as police arrested 2,543 blacks and whites between May 2, 1963 and May 7, 1963. Under intense pressure, the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce reached an agreement on May 9 with black leaders to desegregate public facilities in ninety days, to hire blacks as clerks and salespersons in sixty days, and to release demonstrators without bail in return for an end to the protests.

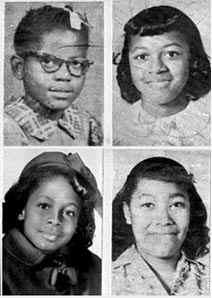

King’s goal was nonviolent social change, but the short-term results of the protests were violence and confrontation. On May 11, white extremists firebombed an integrated motel. That same night, a bomb destroyed the home of King’s brother. Shooting incidents and racial confrontations quickly spread across the South. In June, an assassin, armed with a Springfield rifle, ambushed 37-year-old Medgar Evers, the NAACP field representative in Mississippi, and shot him in the back. In September, an explosion destroyed Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing four black girls and injuring fourteen others. Segregationists had planted ten to fifteen sticks of dynamite under the steps of the fifty-year-old church building. That same day, a sixteen-year-old black Birmingham youth was shot from behind by a police shotgun, and a thirteen-year-old boy was shot while riding his bicycle. All told, ten people died during racial protests in 1963, 35 black homes and churches were firebombed, and 20,000 people were arrested during civil rights protests.