Legal Battle to End of Segregation

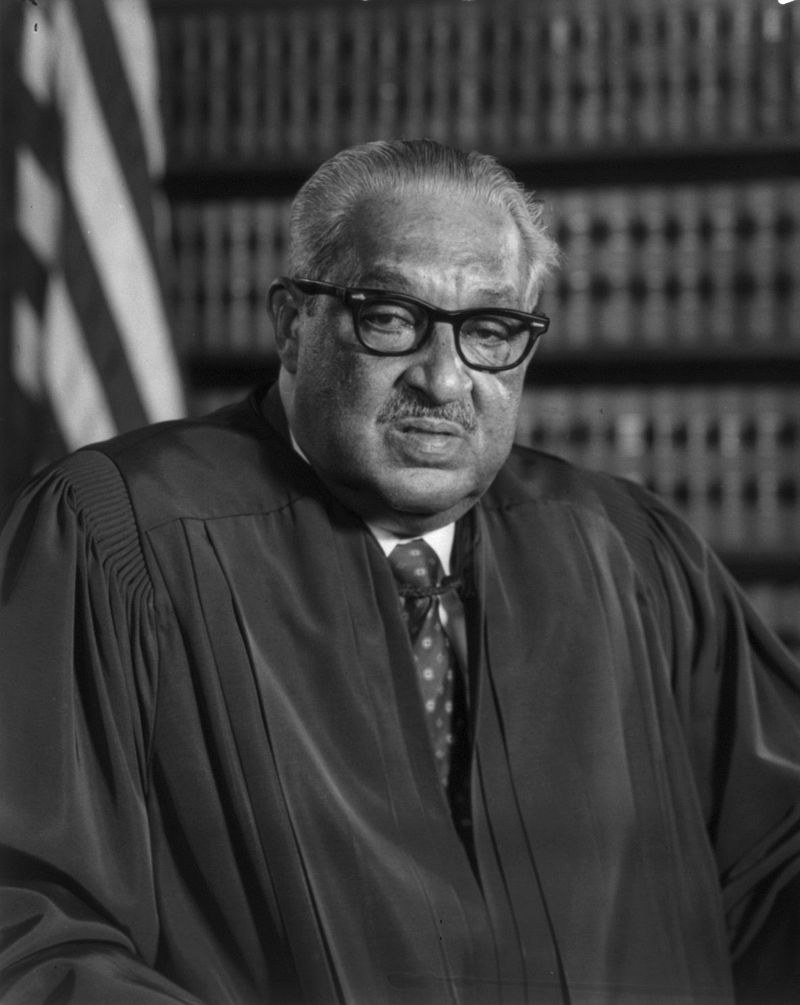

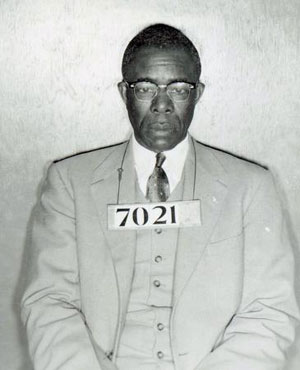

Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall laid the legal foundation for the end of segregation in the South. With the legislative and executive branches of government largely indifferent to racial discrimination, Marshall turned to the courts to prove that separate facilities for blacks and whites were inherently unequal. He won 29 of the 32 cases he argued before the Supreme Court. In his biggest victory, Brown v. Board of Education (1954) of Topeka, Kansas, he persuaded a unanimous Supreme Court to rule that the “separate but equal” doctrine was unconstitutional.

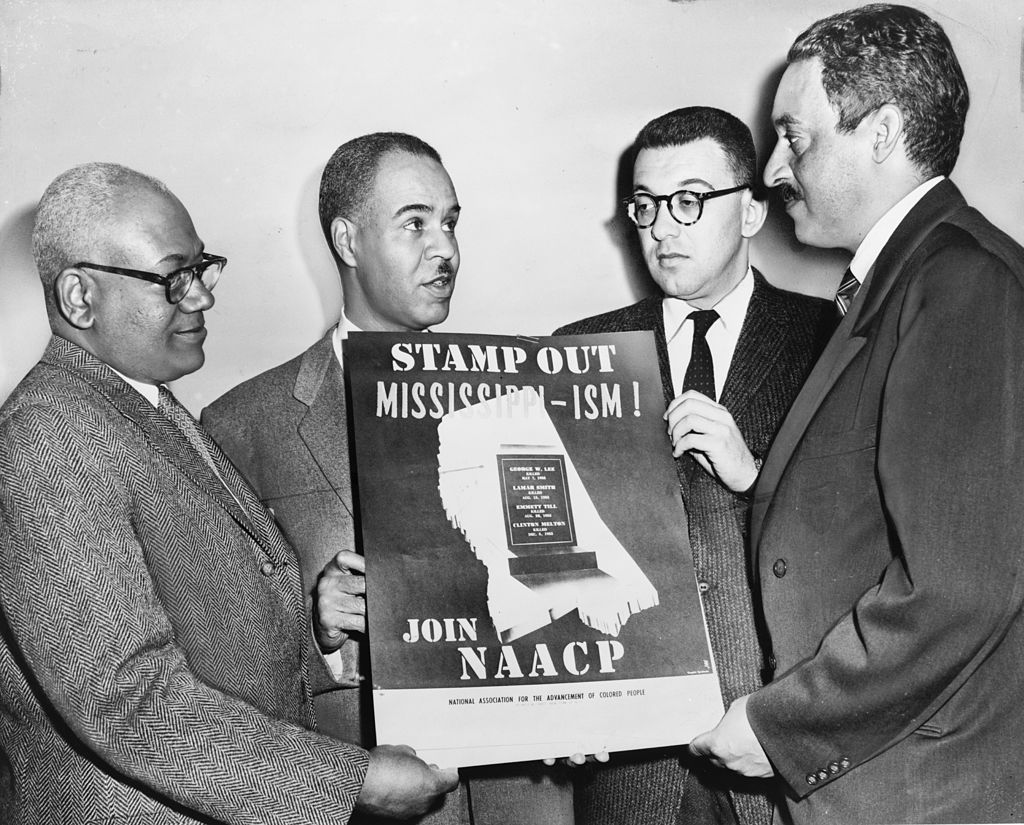

For nearly three decades, Marshall had chipped away at the laws upholding segregation. As the NAACP’s lead counsel, he won equal pay for black teachers, forced segregated courts to allow blacks to serve on juries, and ended the use of restrictive covenants that barred blacks and Jews from segregated neighborhoods. He also persuaded the Supreme Court to end the practice of all-white primaries and to outlaw segregated seating on interstate buses and trains.

He was the target of numerous death threats. On at least two occasions, he was threatened by lynch mobs.

Thurgood Marshall was born in Baltimore, Maryland—a city in which an African American could not become a licensed plumber until 1949 and where an interracial tennis match in 1948 resulted in 34 arrests. Marshall attended a segregated high school in Baltimore and then went to Lincoln University, where the student body was all black and the faculty all white. His classmates included the poet Langston Hughes and Kwame Nkrumah, one of the leaders in Africa’s decolonization.

Because the University of Maryland Law School refused to accept blacks, his mother had to pawn her engagement and wedding rings so that he could attend Howard Law School. Marshall graduated first in his law school class. In 1935, when he was just 26-years-old and only two years out of law school, he got revenge against the University of Maryland Law School when he persuaded a judge to order the university to admit a black student (there were no separate black law schools in the state at that time).

In 1938, at the age of thirty, Marshall became the NAACP’s chief counsel. Convinced that a direct attack on the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) decision and its doctrine of separate but equal would fail, he initially directed his attention at areas where Southern states made no provision for African Americans, such as the systematic exclusion of blacks from professional schools, juries, and primary elections. Only when he had won these path-breaking cases did he move on to attack segregation outright. Few Americans have done so much to change our nation and to help it live up to the ideals on which it was founded.

In 1961, Marshall became a judge on the Second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson appointed him to the post of solicitor general, the government’s chief trial lawyer. Two years later, Marshall became the first African American to serve on the Supreme Court.

When Marshall died in 1993 at the age of 84, his dream of equality and integration had only been partially realized. In that year, 39 years after the Brown decision, two-thirds of African American children attend primarily black schools. A tribute to Marshall at the time of his death underscores his significance: “We make movies about Malcolm X, we get a holiday to honor Dr. Martin Luther King, but every day we live with the legacy of Justice Thurgood Marshall.”

The Significance of World War II and the Cold War

World War II dramatized the glaring contradiction between the American ideal of equal rights and the reality of racial inequality. The Cold War struggle between the Soviet Union and the United States for hearts and minds worldwide underscored that contradiction.

As president, Harry S. Truman struggled to overcome this contradiction. He named the first African American, William H. Hastie, to the federal bench. He ordered the integration of the armed forces. Almost all of his civil rights proposals, however, including bills to outlaw the poll tax and suppress lynching, were defeated because of opposition from white Southern Democrats.

Simple Justice

In 1849, the Massachusetts’ Supreme Judicial Court ruled that the city of Boston had done nothing improper when it required a five-year-old African American girl, Sarah Robert, to walk past white elementary schools and to attend an all-black segregated school. The court rejected the argument made by her lawyers, the abolitionist and U.S. Senator Charles Sumner and African American attorney Robert Morris, that segregated schooling “brand[s] a whole race with the stigma of inferiority and degradation.”

In 1950, Oliver Brown, a railroad worker, filed suit against the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas, some 101 years after the Robert’s case. His daughter, eight-year-old Linda, was a third-grader at the all-black Monroe Elementary School. To reach her school, she had to walk half a mile through a railroad switchyard to catch a bus, even though an all-white elementary school was only seven blocks away.

Topeka’s white lawyers argued that Monroe Elementary School was identical architecturally to Topeka’s white schools. And, they noted, that there were more African American teachers than white teachers with Master’s degrees. The schools were separate but equal, they insisted. Brown’s attorney argued that even if the facilities were equal, the very fact of racial discrimination was detrimental to African American children.

Brown was one of eighteen black Topeka parents challenging segregation. At the time that he sued the Topeka school board, similar cases were filed in Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. In all but the Delaware case, lower courts had ruled that segregation in public schools was permissible as long as the separate facilities were equal. The Supreme Court consolidated the cases.

Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund used sociological evidence to show that segregation harmed black children’s self-esteem. The sociologist Kenneth Clark testified that ten of sixteen black children preferred a white doll to a black doll in a test. Eleven of the children said that the black doll looked “bad.”

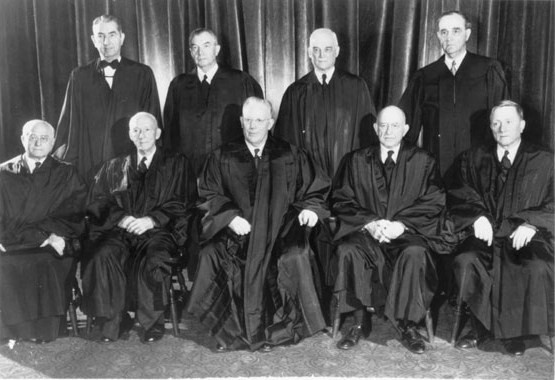

On May 17, 1954, a unanimous Supreme Court handed down its decision. It ruled that segregated schools are inherently unequal and unconstitutional. The court stressed that the badge of inferiority stamped on minority children by segregation hindered their full development no matter how equal the facilities. “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” wrote Chief Justice Earl Warren.

A great deal of behind-the-scenes maneuvering took place before the court handed down its decision. The previous chief justice, Fred M. Vinson, was against striking down segregation. His sudden death led Justice Felix Frankfurter to say privately that Vinson’s death was “the first solid piece of evidence I’ve ever had that there really is a God.”

When President Truman was succeeded in early 1953 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the court ordered the case to be re-argued and asked the government to file another brief. The Justice Department sided with the African American plaintiffs.

President Eisenhower, who was sympathetic to Southern whites, invited Chief Justice Earl Warren to a White House dinner, where the president told him: “These [Southern whites] are not bad people. All they are concerned about is to see that their sweet little girls are not required to sit in school alongside some big overgrown Negroes.” Nevertheless, the Justice Department sided with the African American plaintiffs.

A number of the Supreme Court justices feared that ordering immediate desegregation would unleash turmoil in the South. In order to win a nine to zero vote on the case and the moral authority that a unanimous decision would carry, Chief Justice Earl Warren agreed in a 1955 decision that schools be desegregated with “all deliberate speed.” This contradictory phrase entailed a call for gradual desegregation. At the time, seventeen states had segregated school systems, and 99 percent of black students in the South attended all-black schools.

Some school districts complied immediately, including those in Washington, D.C. Military bases in the South also immediately dismantled their dual school system. But most Southern members of Congress pledged to “use all lawful means” to reverse the decision. It was not until the 1970s that some school districts, including those in Boston, Massachusetts, Charlotte, North Carolina, and Louisville, Kentucky, were forced by the federal courts to implement busing plans to desegregate their schools.

In an editorial headlined “More Powerful Than All the Bombs,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch hailed the decision as “a great and just act of judicial statesmanship…The great body of victors is the people of the United States. Through their Supreme Court they have thrown onto the junk heap one of the worst frauds ever devised—the specious notion that in a democracy, education could be separate and, at the same time, equal.”

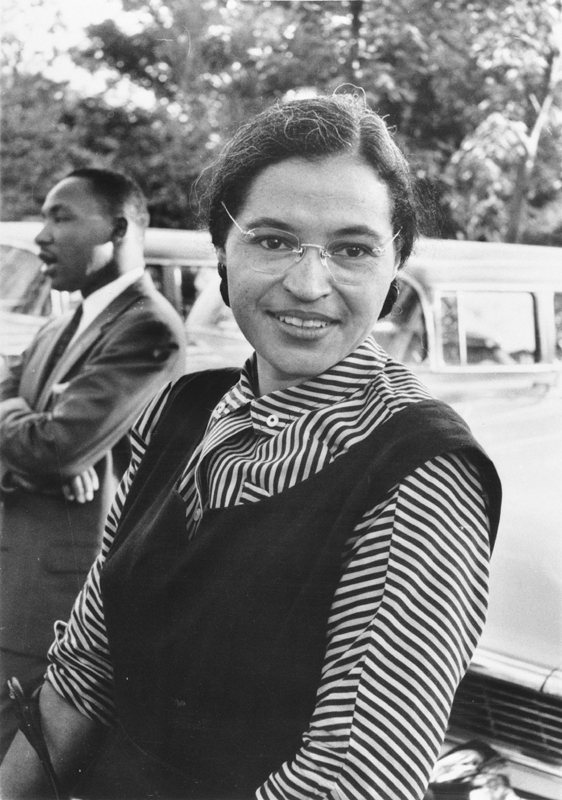

The Mother of the Civil Rights Movement

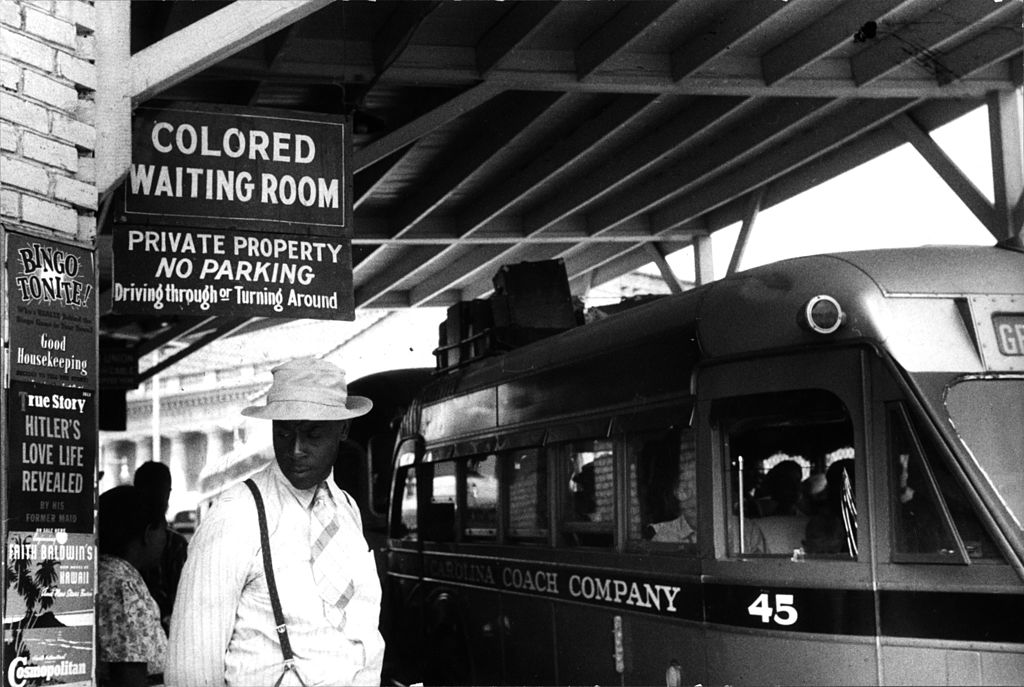

This event was the symbolic beginning of the modern Civil Rights Movement. Rosa Parks, an Alabama seamstress, refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus to a white man. A volunteer secretary for the Montgomery branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a veteran of the Civil Rights Movement since the early 1930s, Parks was returning from work at a department store on December 1, 1955. The bus filled up, whites in the front and blacks in the back. The driver ordered four blacks in the front of the black section of the bus to get up and make room for whites. Three did, but Mrs. Parks did not. She was arrested under a city ordinance that mandated segregated buses and was fined $10 plus $4 court costs.

At the time that she refused to give up her seat, only 31 African Americans in Montgomery were registered to vote. Her act of defiance, however, shook the foundations of segregation.

Her story is filled with myths. For one thing, her refusal to give up her seat was not the product of a premeditated NAACP plan. Rather, it was a spontaneous decision, she later explained. She had been abused and humiliated one time too many:

Just having paid for a seat and riding for only a couple of blocks and then having to stand was too much. These other persons had got on the bus after I did. It meant that I didn’t have a right to do anything but get on the bus, give them my fare, and then be pushed wherever they wanted me…There had to be a stopping place, and this seemed to have been the place for me to stop being pushed around and to find out what human rights I had, if any.

The local NAACP had been searching for years for a woman to defy the Montgomery segregation law. But the two women who had violated the law earlier in the year had been vulnerable to character attacks in court and in the white press. Rosa Parks did not drink, smoke, or curse. She had a steady job and went to church each week. She was soft-spoken and had a serene demeanor. Her impeccable moral character made her the ideal person to contest the case in court.

With support from the local NAACP, a boycott was organized to show support for Parks. Montgomery’s African Americans shared rides, took taxis, or walked to work. Mrs. Parks and many others were fired. There were bombings, beatings, and lawsuits. In February 1956, Parks and a hundred others were charged with conspiracy.

When the boycott started, community leaders arranged for eighteen black taxis in the city to carry passengers for the same ten cent fare as a bus. When the city passed an ordinance requiring a minimum 45 cent fare, 150 people volunteered their cars.

The boycott gained national attention with the charismatic leadership of a 26-year-old minister, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. In November 1956, the Supreme Court affirmed a lower court ruling that threw out the Montgomery bus ordinance. After 381 days, the Montgomery bus boycott was over.

Rosa Parks was not simply a seamstress. She had been active for years as a volunteer secretary to the Montgomery NAACP and its leader, civil rights crusader E.D. Nixon. The daughter of an itinerant carpenter and a school teacher, Rosa Louise McCauley had been born in Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1913. She attended a one-room school and then went on to the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, a vocational training institution. Her education was cut short by her mother’s illness, and she went to work at a textile plant, where she became a seamstress.

In 1932, she married Raymond Parks, a barber who was active in the struggle for voting rights for African Americans. In 1943, she was evicted from a city bus for boarding through the front door; black passengers were forced to pay at the front of the bus, get off, and re-enter through the rear. In 1955, she had attended a demonstration on desegregation and civil disobedience at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. She later said that her training at the school helped her to take a stand against segregation.

In later life, her views ranged between the non-violence of Martin Luther King and the militancy of Malcolm X. “I don’t believe in gradualism,” she told an interviewer, “or that whatever is to be done for the better should take forever to do.” By holding on to her seat, Rosa Parks illustrated how one person’s spontaneous act of courage and defiance can alter the course of history.

Eisenhower and Civil Rights

President Dwight D. Eisenhower was a reluctant battler for civil rights. Upon taking office, the Texas-born president ordered an end to segregation “in the District of Columbia, including the federal government, and any segregation in the armed forces.” In 1954, he tried to persuade Chief Justice Earl Warren to avoid antagonizing the white South by ordering immediate desegregation.

Nevertheless, the president was confident that city and state officials would obey desegregation orders. “I can’t imagine any set of circumstances that would ever induce me to send federal troops…to enforce the orders of a federal court, because I believe that the common sense of American will never require it,” he told reporters in July 1957.

At that time, Congress was in the process of enacting the first civil rights bill since the 1870s, which would create a federal civil rights commission, a civil rights division within the Justice Department, and new federal authority to enforce voting rights.

Little Rock

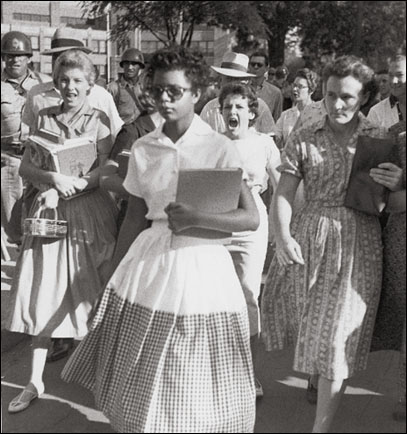

The first major confrontation between states’ rights and the Supreme Court’s school integration decision occurred in Little Rock, Arkansas, in the summer of 1957. Eighteen African American students were chosen to integrate Little Rock’s Central High School to comply with the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision. By Labor Day, only nine were still willing to serve as foot soldiers in freedom’s march.

Arkansas seemed an unlikely place for a confrontation over civil rights. Its largest newspapers were generally supportive of desegregation, and several Arkansas cities had already integrated their public schools. The public library and bus system were desegregated, earning Little Rock a reputation as a progressive town. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus owed his re-election in 1956 to black voters.

Ironically, Faubus, responding to polls that showed 85 percent of the state’s residents opposed school integration, tried to block desegregation by directing the Arkansas National Guard to keep the nine teenagers from enrolling in the all-white Central High. He said that “blood would run in the streets” if the Central High School was integrated.

For three weeks, the National Guard, under orders from the governor, prevented the nine students from entering the school. President Eisenhower privately pressed Faubus to comply with the court order. When Faubus refused to comply, the president responded by federalizing the Arkansas National Guard and sending in 1,000 paratroopers from the Army’s 101st Airborne Division to escort the students into the school.

An angry white mob hurled racial epithets. Inside the school, there were still separate restrooms and drinking fountains for black and white students. During the school year, the African American students were ostracized and physically harassed. They were shoved against lockers, tripped down stairways, and taunted by their classmates. Not all the African American students were able to turn the other cheek. One was expelled for dumping a bowl of soup on a classmate’s head. The remaining students were greeted the next day with a sign that said, “One down, eight more to go.”

Only one of the Little Rock nine graduated from Central High. In the fall of 1958, Governor Faubus shut the public high schools down to prevent further integration. The schools did not re-open for a year.

Daisy Bates, the president of Arkansas’s NAACP, spearheaded the drive to integrate Central High. Before and after school, she would have the students gather at her home for prayer and counsel. During the integration struggle, rocks were thrown through her windows and a burning cross was placed on her roof. In 1963, Bates, whose mother had been murdered by three white men in an attempted rape, was the only woman to speak at the 1963 March on Washington.

Of the Little Rock nine, one student became assistant secretary of Housing and Urban Development under President Jimmy Carter. The others became an accountant, an investment banker, a journalist, a social worker, a psychologist, a teacher, a real estate broker, and a writer. Only one remained in Little Rock.

Nearly half a century after the Little Rock nine entered Central High School, the city’s school system still struggles with integration. Today, almost fifty percent of the white students who live in the district do not enroll in the public school system. Despite busing 14,000 of its 25,000 students to achieve racial balance, 18 of the district’s 49 schools have at least 75 percent black enrollment.