The Decline of the New Deal

The New Deal in Decline

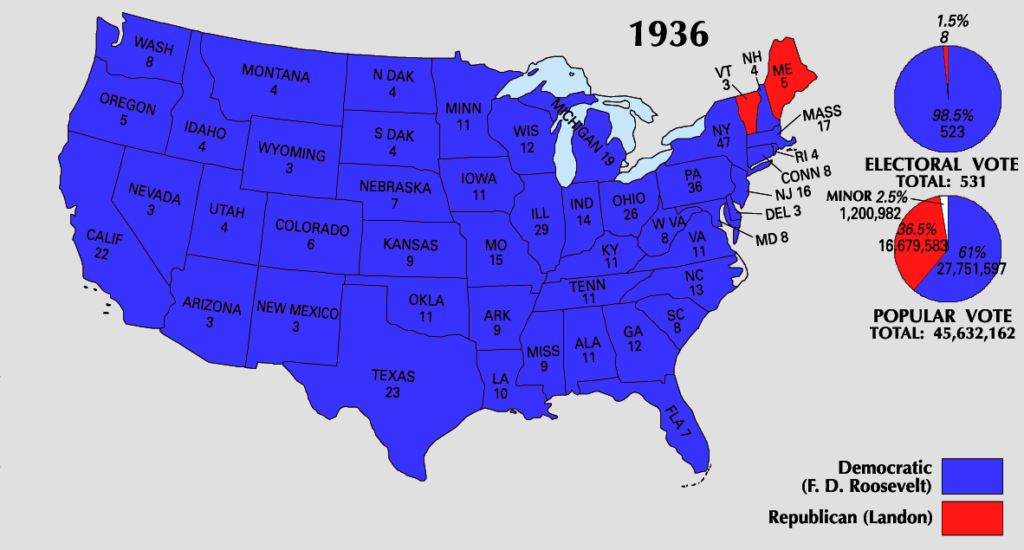

President Roosevelt was overwhelmingly re-elected in the election of 1936. He carried every state but Maine and Vermont, easily defeating the Republican Candidate Governor Alf Landon of Kansas. Democrats won an equally lopsided victory in the congressional races: 331 to 89 seats in the House and 76 to 16 seats in the Senate.

In his second inaugural address in early 1937, Franklin Roosevelt promised to press for new social legislation. “I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished,” he told the country.

Yet instead of pursuing new reforms, he allowed his second term to bog-down in political squabbles. He wasted his energies on an ill-conceived battle with the Supreme Court and an abortive effort to purge the Democratic Party.

Court Packing

On “Black Monday,” May 27, 1935, the Supreme Court struck down a basic part of Roosevelt’s program of recovery and reform. A kosher chicken dealer sued the government, charging that the NRA was unconstitutional. In its famous “dead chicken” decision, Schechter v. the U.S., the court agreed. The case affirmed that Congress had delegated excessive authority to the president and had improperly involved the federal government in regulating interstate commerce. Complained Roosevelt, “We have been relegated to the horse-and-buggy definition of interstate commerce.”

In June 1936, the court ruled the Agricultural Adjustment Act—another of the measures enacted during the first 100 days—unconstitutional. Then six months later, the high court declared a New York state minimum wage law invalid. Roosevelt was aghast. The court, he feared, had established a “‘no-man’s land’ where no government, state or federal, can function.”

Roosevelt feared that every New Deal reform, such as the prohibition on child labor or regulation of wages and hours, was at risk. In 1936, his supporters in Congress responded by introducing over a hundred bills to curb the judiciary’s power. After his landslide re-election in 1936, the president proposed a controversial “court-packing scheme.” The plan proposed to reorganize the Supreme Court. Roosevelt sought to make his opponents on the Supreme Court resign so that he could replace them with justices more sympathetic to his policies. To accomplish this, he announced a plan to add one new member to the Supreme Court for every judge who had reached the age of seventy without retiring (six justices were over seventy). To offer a carrot with the stick, Roosevelt also outlined a generous new pension program for retiring federal judges.

The court-packing scheme was a political disaster. Conservatives and liberals alike denounced Roosevelt for attacking the separation of powers, and critics accused him of trying to become a dictator. Fortunately, the Court itself ended the crisis by shifting ground. In two separate cases, the Court upheld the Wagner Act and approved a Washington state minimum wage law, furnishing proof that it had softened its opposition to the New Deal.

Yet Roosevelt remained too obsessed with the battle to realize he had won the war. He lobbied for the court-packing bill for several months, squandering his strength on a struggle that had long since become a political embarrassment. In the end, the only part of the president’s plan to gain congressional approval was the pension program. Once it passed, Justice Willis Van Devanter, the most obstinate New Deal opponent on the Court, resigned. By 1941 Roosevelt had named five justices to the Supreme Court. Few legacies of the president’s leadership proved more important. The new “Roosevelt Court” significantly expanded the government’s role in the economy and in civil liberties.

Depression of 1937

The sweeping Democratic electoral victory in 1936 was followed by a deep economic relapse known as the “Roosevelt Recession.” In just a few months, industrial production fell by 40 percent, unemployment rose by 4 million, stock prices plunged 48 percent.

Several factors contributed to the “little depression.” Reassured by good economic news in 1936, Roosevelt slashed government spending the following year. The budget cuts knocked the economy into a tailspin. Roosevelt’s virulent attacks on “economic royalists” also undermined business confidence.

The reform spirit was gone by the end of 1938. A conservative alliance of Southern Democrats and northern Republicans in Congress blocked all efforts to expand the New Deal. In the congressional elections of 1938, Roosevelt campaigned against five conservative senators who opposed the New Deal. Nevertheless, all won re-election. Roosevelt’s failures showed conservative Democrats that they could defy the president with impunity.

Legacy of the New Deal

The New Deal did not end the Depression. Nor did it significantly redistribute income. It did, however, provide Americans with economic security that they had never known before. The New Deal legacies include unemployment insurance, old age insurance, and insured bank deposits. The Wagner Act reduced violence in labor relations. The Securities and Exchange Commission protected stock market investments of millions of small investors. The Federal Housing Administration and Fannie Mae enabled a majority of Americans to become homeowners.

The New Deal’s greatest legacy was a shift in government philosophy. As a result of the New Deal, Americans came to believe that the federal government has a responsibility to ensure the health of the nation’s economy and the welfare of its citizens.