Exclusion and Political Realignment

Social Security

The 1935 Social Security Act, a goal of reformers since the Progressive era, aimed to alleviate the plight of America’s visibly poor—the elderly, dependent children, and the handicapped. A major political victory for Roosevelt, the Social Security Act was a triumph of social legislation. Financed by the federal government and the states, the act offered workers age 65 or older monthly stipends based on previous earnings, and it gave the indigent elderly small relief payments. In addition, it provided assistance to blind and handicapped Americans and to dependent children who did not have a wage-earning parent. The act also established the nation’s first federally-sponsored system of unemployment insurance. Mandatory payroll deductions levied equally on employees and employers financed both the retirement system and the unemployment insurance.

Conservatives argued that the Social Security Act placed the United States on the road to socialism. The legislation was also profoundly disappointing to reformers, who demanded “cradle to grave” protection as the birthright of every American. The new system authorized pitifully small payments. Its retirement system left huge groups of workers uncovered, such as migrant workers, civil servants, domestic servants, merchant seamen, and day laborers. Its budget came from a regressive tax scheme that placed a disproportionate tax burden on the poor, and it failed to provide health insurance.

Despite these criticisms, the Social Security Act introduced a new era in American history. It committed the government to a social welfare role by providing for elderly, disabled, dependent, and unemployed Americans. By doing so, the act greatly expanded the public’s sense of entitlement and the support people expected government to give to all citizens.

African Americans and the New Deal

Until the New Deal, blacks had shown their traditional loyalty to the party of Abraham Lincoln by voting overwhelmingly Republican. By the end of Roosevelt’s first administration, however, one of the most dramatic voter shifts in American history had occurred. In 1936, some 75 percent of black voters supported the Democrats. Blacks turned to Roosevelt, in part, because his spending programs gave them a measure of relief from the Depression and, in part, because the GOP had done little to repay their earlier support.

Still, Roosevelt’s record on civil rights was modest at best. Instead of using New Deal programs to promote civil rights, the administration consistently bowed to discrimination. In order to pass major New Deal legislation, Roosevelt needed the support of southern Democrats. He backed away from equal rights to avoid antagonizing Southern whites, although his wife, Eleanor, did take a public stand in support of civil rights

Most New Deal programs discriminated against blacks. The NRA, for example, not only offered whites the first crack at jobs, but authorized separate and lower pay scales for blacks. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) refused to guarantee mortgages for blacks who tried to buy in white neighborhoods, and the CCC maintained segregated camps. Furthermore, the Social Security Act excluded those job categories blacks traditionally filled.

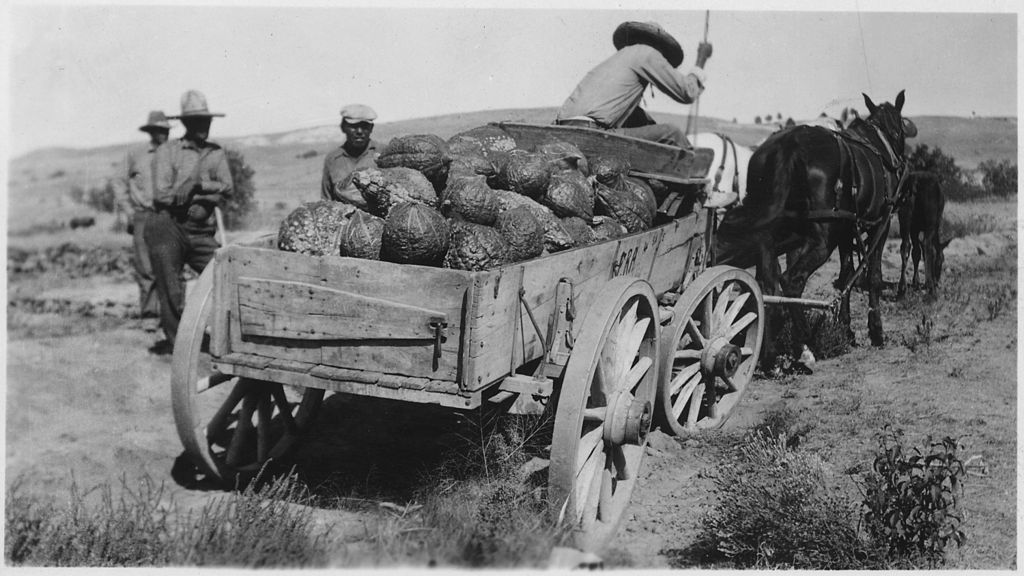

The story in agriculture was particularly grim. Since forty percent of all black workers made their living as sharecroppers and tenant farmers, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) acreage reduction hit blacks hard. White landlords could make more money by leaving land untilled than by putting land back into production. As a result, the AAA’s policies forced more than 100,000 blacks off the land in 1933 and 1934. Even more galling to black leaders, the president failed to support an anti-lynching bill and a bill to abolish the poll tax. Roosevelt feared that conservative Southern Democrats, who had seniority in Congress and controlled many committee chairmanships, would block his bills if he tried to fight them on the race question.

Yet, the New Deal did record a few gains in civil rights. Roosevelt named Mary McLeod Bethune, a black educator, to the advisory committee of the National Youth Administration (NYA). Thanks to her efforts, blacks received a fair share of NYA funds. The WPA was colorblind, and blacks in Northern cities benefited from its work relief programs. Harold Ickes, a strong supporter of civil rights who had several blacks on his staff, poured federal funds into black schools and hospitals in the South. Most blacks appointed to New Deal posts, however, served in token positions as advisors on black affairs. At best, they achieved a new visibility in government.

Hidden History

Mexican Americans

In February 1930, in San Antonio, Texas, 5,000 Mexicans and Mexican Americans gathered at the city’s railroad station to depart the United States for settlement in Mexico. In August, a special train carried another 2,000 to central Mexico.

Most Americans are familiar with the forced relocation in 1942 of 112,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast to internment camps. Far fewer are aware that during the Great Depression, the Federal Bureau of Immigration (after 1933, the Immigration and Naturalization Service) and local authorities rounded up Mexican immigrants and naturalized Mexican American citizens and shipped them to Mexico to reduce relief roles. In a shameful episode, more than 400,000 repatriados, many of them citizens of the United States by birth, were sent across the U.S.-Mexico border from Arizona, California, and Texas. The Mexican-born population in Texas was reduced by a third. Los Angeles also lost a third of its Mexican population. In Los Angeles, the only Mexican American student at Occidental College sang a painful farewell song to serenade departing Mexicans.

Even before the stock market crash, there had been intense pressure from the American Federation of Labor and municipal governments to reduce the number of Mexican immigrants. Opposition from local chambers of commerce, economic development associations, and state farm bureaus stymied efforts to impose an immigration quota, however, rigid enforcement of existing laws slowed legal entry. In 1928, United States consulates in Mexico began to apply with unprecedented rigor the literacy test legislated in 1917.

After President Hoover appointed William N. Doak as Secretary of Labor in 1930, the Bureau of Immigration launched intensive raids to identify aliens liable for deportation. The secretary believed that removal of undocumented aliens would reduce relief expenditures and free jobs for native-born citizens. Altogether, 82,400 were involuntarily deported by the federal government.

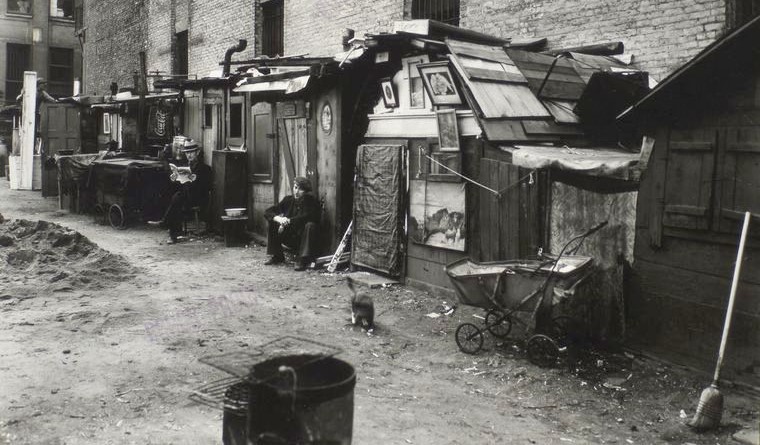

Federal efforts were accompanied by city and county pressure to repatriate destitute Mexican American families. In February 1931, Los Angeles police surrounded and raided a downtown park and detained some 400 adults and children. The threat of unemployment, deportation, and loss of relief payments led tens of thousands of people to leave the United States.

Deportation efforts were not confined to the Southwest. There were deportations from Alabama, Alaska, Michigan, and Mississippi. Many of those removed–-perhaps as many as sixty percent—were U.S. citizens.

Still, the New Deal offered Mexican Americans some help. The Farm Security Administration established camps for migrant farm workers in California, and the CCC and WPA hired unemployed Mexican Americans on relief jobs. Many, however, did not qualify for relief assistance because they did not meet residency requirements as migrant workers. Furthermore, agricultural workers were not eligible for benefits under workers’ compensation, Social Security, and the Wagner Act (also known as the National Labor Relations Act).

Native Americans

The so-called “Indian New Deal” was the only bright spot in the administration’s treatment of minorities. In the late nineteenth century, American Indian policy had begun to place a growing emphasis on erasing a distinctive Native American identity. In 1871, Congress ended the practice of treating tribes as sovereign nations in an attempt to weaken the authority of tribal leaders. An effort was also made to undermine older systems of tribal justice. Accordingly, Congress created a Court of Indian Offenses in 1882 to prosecute Indians who violated government laws and rules. Indian schools took Indian children away from their families and tribes and sought to strip them of their tribal heritage. School children were required to trim their hair and to speak English and were prohibited from practicing Indian religions.

The 1887 Dawes Act was the culmination of these policies. The act allocated reservation lands to individual Indians. The purpose of the act was to encourage Indians to become farmers; however, the plots were too small to support a family or to raise livestock. Government policies reduced Indian-owned lands from 155 million acres to just 48 million acres in 1934.

When Roosevelt became president in 1933, he appointed a leading reformer, John Collier, as commissioner of Indian affairs. At Collier’s request, Congress created the Indian Emergency Conservation Program (IECP), a CCC-type project for the reservations which employed more than 85,000 Indians. Collier also made certain that the PWA, WPA, CCC, and NYA hired Native Americans.

Collier had long been an opponent of the fifty-year-old government allotment program which partitioned and distributed tribal lands. In 1934, he persuaded Congress to pass the Indian Reorganization Act. The act terminated the allotment program of the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, provided funds for tribes to purchase new land, offered government recognition of tribal constitutions, and repealed prohibitions on Native American languages and customs. That same year, federal grants were provided to local school districts, hospitals, and social welfare agencies to assist Native Americans. The Indian New Deal also led the government to recognize tribal constitutions.